East Timorese Youth in the Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Staging Lusophony: politics of production and representation in theater festivals in Portuguese-speaking countries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70h801wr Author Martins Rufino Valente, Rita Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Staging Lusophony: politics of production and representation in theater festivals in Portuguese-speaking countries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Rita Martins Rufino Valente 2017 © Copyright by Rita Martins Rufino Valente 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Staging Lusophony: politics of production and representation in theater festivals in Portuguese-speaking countries by Rita Martins Rufino Valente Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair My dissertation investigates the politics of festival curation and production in artist-led theater festivals across the Portuguese-speaking (or Lusophone) world, which includes Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia. I focus on uses of Lusophony as a tactics to generate alternatives to globalization, and as a response to experiences of racialization and marginalization stemming from a colonial past. I also expose the contradictory relation between Lusophony, colonialism, and globalization, which constitute obstacles for transnational tactics. I select three festivals where, I propose, the legacies of the colonial past, which include the contradictions of Lusophony, become apparent throughout the curatorial and production processes: Estação da Cena Lusófona (Portugal), Mindelact – Festival Internacional de Teatro do Mindelo (Cabo Verde), and Circuito de Teatro em Português (Brazil). -

Representações Sobre Reality Shows: O Caso De Desilusões Futuristas E

77 Representações sobre reality shows: o caso de Desilusões Futuristas e Morte ao Vivo 1 Representations of reality shows: the case of ‘Le couplé témoin’ and ‘La mort en direct’ 7 Valéria Cristina Lopes Wilke 2 Leila Beatriz Ribeiro 3 Carmen Irene Correia de Oliviera 4 RESUMO O objetivo deste trabalho é discutir a relação entre a exposição da vida privada em esferas midiáticas, analisando duas representações fílmicas – Desilusões futuristas e Morte ao vivo – que apresentam experimentações diferentes dentro modelo dos reality shows. Algumas estratégias estão em destaque e marcam as diferenças e semelhanças dessas duas produções. Partiremos das considerações sobre a sociedade do espetáculo (Debord) e sobre os reality shows para discutir o modo de representação, nos filmes, deste gênero televisivo e das relações presentes entre as instâncias envolvidas. Nas duas produções analisadas, percebemos uma leitura crítica centrada nas intencionalidades da produção e na exposição dos participantes, mas, também, uma focalização no papel daqueles que são os responsáveis diretos pela exposição ao vivo. PALavRAS-CHave realitiy shows; sociedade do espetáculo; filme; Desilusões futuristas; Morte ao vivo. ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to discuss the relationship between exposure levels of privacy for media, analyzing two filmic representations – Le couple témoin and La mort en direct - presenting different experiments within the model of reality shows. Some strategies are highlighted and mark the differences and similarities of these two productions. We leave the considerations about the society of the spectacle (Debord), on the reality show to discuss the mode of representation, in movies, this television genre and present relations between the actors involved. -

Australia Day and Citizenship Ceremony 2020

MAYOR ROBERT BRIA AUSTRALIA DAY CELEBRATION & CITIZENSHIP CEREMONY 9:30am – 11am Sunday, 26 January 2020 St Peters Street, St Peters RUN ORDER 9.30am Mayor’s Welcome Speech 9.40am Australia Day Awards 9.55am Australia Day Ambassador Speech 10.00am Australian Girl’s Choir 10.10am commence Citizenship Ceremony 10.12am Speeches from MPs 10.20am Oath and Affirmation of Citizenship 10.45am National Anthem 10.50am Closing remarks 1 Good morning and welcome to the City of Norwood Payneham & St Peters Australia Day Celebration and Citizenship Ceremony. My name is Robert Bria. I am the Mayor of the City of Norwood Payneham & St Peters and it is my very great pleasure to welcome you all here this morning to celebrate our national holiday. I would firstly like to acknowledge this land that we meet on today is the traditional land of the Kaurna people and that we respect their spiritual connection with their country. We also acknowledge the Kaurna People as the custodians of the greater Adelaide region and that their cultural and heritage beliefs are still important to the living Kaurna people today. 2 I am delighted to welcome our distinguished guests: Hon Steven Marshall MP, Premier of South Australia. Hon Vickie Chapman MP, Deputy Premier of South Australia Michele Lally, Australia Day Ambassador Michelle from the Australian Electoral Commission Welcome to my fellow Elected Members: Carlo Dottore Kevin Duke Kester Moorhouse Garry Knoblauch John Callisto John Minney Evonne Moore Christel Mex Scott Sims 3 Sue Whitington Fay Patterson, and their partners. A warm welcome also to council staff here this morning, in particular he Council’s Chief Executive Officer, Mr Mario Barone PSM. -

Final Version

This research has been supported as part of the Popular Music Heritage, Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity (POPID) project by the HERA Joint Research Program (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, DASTI, ETF, FNR, FWF, HAZU, IRCHSS, MHEST, NWO, RANNIS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007–2013, under ‘the Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities program’. ISBN: 978-90-76665-26-9 Publisher: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Center for Media, Communication and Culture Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers Cover design: Martijn Koster © 2014 Arno van der Hoeven Popular Music Memories Places and Practices of Popular Music Heritage, Memory and Cultural Identity *** Popmuziekherinneringen Plaatsen en praktijken van popmuziekerfgoed, cultureel geheugen en identiteit Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.A.P Pols and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defense shall be held on Thursday 27 November 2014 at 15.30 hours by Arno Johan Christiaan van der Hoeven born in Ede Doctoral Committee: Promotor: Prof.dr. M.S.S.E. Janssen Other members: Prof.dr. J.F.T.M. van Dijck Prof.dr. S.L. Reijnders Dr. H.J.C.J. Hitters Contents Acknowledgements 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Studying popular music memories 7 2.1 Popular music and identity 7 2.2 Popular music, cultural memory and cultural heritage 11 2.3 The places of popular music and heritage 18 2.4 Research questions, methodological considerations and structure of the dissertation 20 3. The popular music heritage of the Dutch pirates 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 The emergence of pirate radio in the Netherlands 28 3.3 Theory: the narrative constitution of musicalized identities 29 3.4 Background to the study 30 3.5 The dominant narrative of the pirates: playing disregarded genres 31 3.6 Place and identity 35 3.7 The personal and cultural meanings of illegal radio 37 3.8 Memory practices: sharing stories 39 3.9 Conclusions and discussion 42 4. -

Brazil Looks to Africa: Lusotropicalism in the Brazilian Foreign Policy Towards Africa

Brazilian Journal of African Studies | Porto Alegre | v. 3, n. 5, Jan./Jun. 2018 | p. 31-45 31 BRAZIL LOOKS TO AFRICA: LUSOTROPICALISM IN THE BRAZILIAN FOREIGN POLICY TOWARDS AFRICA Fernando Sousa Leite1 Introduction When becoming President of Brazil, in January 31st 1961, Jânio Quadros set to execute a number of actions in the international stage, through what was called the Independent Foreign Policy (PEI)2. The foreign policy of this president intended to, among other measures interpreted as unexpected and original, pursue a continent long overlooked in the foreign relations portfolio of the country: Africa. Differently from his predecessor Juscelino Kubitschek, that defended a “rearguard foreign policy, in opposition to an advanced internal policy” (Rodrigues 1963, 392), Quadros will assume what can be considered an avant-garde position in the foreign scope, even though he developed an internal policy interpreted as conservative. Despite Jânio Quadros representing a ludicrous character in the national historiography, the idealization of the Africanist strand of his foreign policy was based, overall, on pragmatism. It was about making Brazil’s foreign performance meet the demands of that time, an attempt to adjust its actions to the then undergoing set of modifications in the international relations. The way in which this inflexion towards Africa was executed can be criticized under different aspects, but the diagnosis of the necessity of an opening to Africa can be adduced as correct. The economy dictated the paths to be followed by the foreign policy. In a rational perspective, the addition of the recognition of the independence of the African territories to the international action calculations of Brazil 1 Rio Branco Institute, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brasília, Brazil. -

Intersections of Empire, Post-Empire, and Diaspora: De-Imperializing Lusophone Studies

Intersections of Empire, Post-Empire, and Diaspora: De-Imperializing Lusophone Studies CRISTIANA BASTOS Universidade de Lisboa Abstract: The present article opens with a generic plea for the de-imperialization of Lusophone studies. A de-imperial turn should allow researchers to explore more thoroughly the experiences of diaspora and exile that an empire-centered history and its spin-offs have obfuscated; it should also help to de-essentialize depictions of Portuguese heritage and culture shaped by these narratives. Such a turn promises to address the multiple identifications, internal diversities, and racialized inequalities produced by the making and unmaking of empire. My contribution consists of a few ethnographic-historic case studies collected at the intersections of empire, post-empire, and diaspora. These include nineteenth- century diasporic movements that brought Portuguese subjects to competing empires; past and present celebrations of heritage in diasporic contexts; culture wars around representations; and current directions in post-imperial celebrations and reparations. Keywords: Portugal, de-empire, plantations, labor, migrations, heritage I make a plea in the present article for the de-imperialization of Lusophone studies. I suggest that expanding our scope beyond the geographies of the Portuguese empire will enrich and rescue some of the current discussions on identity and heritage, tradition and change, centrality and peripherality, dependency and development, racism and Lusotropicalism, gender, generation, as well as other issues. 27 Bastos The shape and shadows of empire have powerful afterlives. In spite of the literature that addresses the centrality of migration, displacement, and exile in the overall experience of being Portuguese, mainstream representations of Portuguese identity are, to this day, dominated by evocations of empire—be it through the theme of discoveries or through variations of Lusotropicalism. -

With One Voice Community Choir Program

WITH ONE VOICE COMMUNITY CHOIR PROGRAM We hope being part of this choir program will bring you great joy, new connections, friendships, opportunities, new skills and an improved sense of wellbeing and even a job if you need one! You will also feel the creative satisfaction of performing at some wonderful festivals and events. If you have any friends, family or colleagues who would also like to get involved, please give them Creativity Australia’s details, which can be found on the inside of the front cover of this booklet. We hope the choir will grow to be a part of your life for many years. Also, do let us know of any performance or event opportunities for the choir so we can help them come to fruition. We would like to thank all our partners and supporters and ask that you will consider supporting the participation of others in your choir. Published by Creativity Australia. Please give us your email address and we will send you regular choir updates. Prepared by: Shaun Islip – With One Voice Conductor In the meantime, don’t forget to check out our website: www. Kym Dillon – With One Voice Conductor creativityaustralia.org.au Bridget a’Beckett – With One Voice Conductor Andrea Khoza – With One Voice Conductor Thank you for your participation and we are looking forward to a very Marianne Black – With One Voice Conductor exciting and rewarding creative journey together! Tania de Jong – Creativity Australia, Founder & Chair Ewan McEoin – Creativity Australia, General Manager Yours in song, Amy Scott – Creativity Australia, Program Coordinator -

AUSTRALIAN BUSH SONGS Newport Convention Bush Band Songbook

AUSTRALIAN BUSH SONGS Newport Convention Bush Band Songbook Friday, 11 July 2003 Song 1 All for Me GrOG...........................................................................................................................................................................2 SONG 2 Billy of tea.................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Song 3 BLACK VELVET BAND............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Song 4 BOTANTY BAY.......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Song 5 Click Go the Shears.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Song 6 Dennis O'Reilly............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Song 7 Drovers Dream..............................................................................................................................................................................9 Song 8 Dying Stockman..........................................................................................................................................................................10 -

Society for Ethnomusicology 60Th Annual Meeting, 2015 Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 60th Annual Meeting, 2015 Abstracts Walking, Parading, and Footworking Through the City: Urban collectively entrained and individually varied. Understanding their footwork Processional Music Practices and Embodied Histories as both an enactment of sedimented histories and a creative process of Marié Abe, Boston University, Chair, – Panel Abstract reconfiguring the spatial dynamics of urban streets, I suggest that a sense of enticement emerges from the oscillation between these different temporalities, In Michel de Certeau’s now-famous essay, “Walking the City,” he celebrates particularly within the entanglement of western imperialism and the bodily knowing of the urban environment as a resistant practice: a relational, development of Japanese capitalist modernity that informed the formation of kinesthetic, and ephemeral “anti-museum.” And yet, the potential for one’s chindon-ya. walking to disrupt the social order depends on the walker’s racial, ethnic, gendered, national and/or classed subjectivities. Following de Certeau’s In a State of Belief: Postsecular Modernity and Korean Church provocations, this panel investigates three distinct urban, processional music Performance in Kazakhstan traditions in which walking shapes participants’ relationships to the past, the Margarethe Adams, Stony Brook University city, and/or to each other. For chindon-ya troupes in Osaka - who perform a kind of musical advertisement - discordant walking holds a key to their "The postsecular may be less a new phase of cultural development than it is a performance of enticement, as an intersection of their vested interests in working through of the problems and contradictions in the secularization producing distinct sociality, aesthetics, and history. For the Shanghai process itself" (Dunn 2010:92). -

Significant Features of Fiscal Federalism 1988 Edition

—. ,., .,”,.... ,.,. Preface Rdeaee of this volume of Significant Feahree and public finance analysts find the new as well ofFiscal Federalism represents en important de- as updated information helpful in their research. parture from earlier editions of this report— Of course, given the early publication date, namely, its December publication date. In order certain data series typically found in Significant to respond more readily to the needs of state ax- Feahree were omitted from this volume. Nearly ecutive end legislative oftlcials, their staffs, and all of the omitted series of tables rely on data col- those who interact with them, thk volume is be- lected by the Governments Division of the U.S. ing released immediately prior to the opening of Bureau of the Census—data that were not re- the 1988 state legislative sessions. In the past, leased until December 1987. Based on these data, Significant Features has been released in mid- Volume II of Significant Features, 1988, will be spring. It is hoped that thk early release date will issued in the spring of 1988. The second volume enable the many users of Significant Features to will contain state-by-state information on the make better end more informed decisions baaed distribution of revenue sources for state govern- on more timely information. It is ACIR’S inten- ments, locaI governments and state-locaJ govern- tion to continue issuing Significant Feaiures in ments combined; the distribution of expenditures two volumes, commencing with this 1988 edi- by function (percentage of government budgets tion. devoted to education, highways, public welfare, Thie volume is devoted primarily to federal, etc.) will also be included. -

Newsletter 13. 28-05-2020.Pub

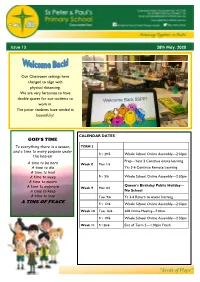

Issue 13 28th May, 2020 Our Classroom settings have changed to align with physical distancing. We are very fortunate to have double spaces for our students to work in. The junior students have settled in beautifully! CALENDAR DATES GOD’S TIME To everything there is a season, TERM 2 and a time to every purpose under Fri 29/5 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm the heaven: Prep—Year 2 Continue onsite learning A time to be born Week 8 Mon 1/6 A time to die Yrs 3-6 Continue Remote Learning A time to heal A time to weep Fri 5/6 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm A time to mourn Queen’s Birthday Public Holiday— A time to embrace Week 9 Mon 8/6 A time to keep No School A time to love Tues 9/6 Yr 3-6 Return to onsite learning A TIME OF PEACE Fri 12/6 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm Week 10 Tues 16/6 SAB Online Meeting—7:00am Fri 19/6 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm Week 11 Fri 26/6 End of Term 2—1:00pm Finish “Seeds of Hope” PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE Dear Families, Seeds of Hope Welcome back to the beautiful smiling faces of our Preps, Year 1s and Year 2s. We have missed you terribly and we are so glad you have returned. Congratulations to you all for being so independent and managing all your bags and belongings all by yourselves. We are so very proud of you all! Our transition back to onsite learning has been exceptionally smooth and the children have been fantastic in adjusting to the changes that have taken place; coming in to school, in their classrooms, in the playground and around the buildings. -

Eliana Pereira De Carvalho O COLONIALISMO EXTEMPORÂNEO

0 UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE-UERN PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO-PROPEG CAMPUS AVANÇADO PROFª MARIA ELISA DE ALBUQUERQUE MAIA-CAMEAM DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ESTRANGEIRAS - DLE PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS-PPGL CURSO DE MESTRADO E DOUTORADO ACADÊMICOS EM LETRAS Eliana Pereira de Carvalho O COLONIALISMO EXTEMPORÂNEO DE ANGOLA, AS RICAS DONAS, DE ISABEL VALADÃO PAU DOS FERROS-RN 2020 0 ELIANA PEREIRA DE CARVALHO O COLONIALISMO EXTEMPORÂNEO DE ANGOLA, AS RICAS DONAS, DE ISABEL VALADÃO Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, da Universidade do Rio Grande do Norte, como requisito à obtenção do título de Doutor em Letras. Linha de Pesquisa: Texto Literário, Crítica e Cultura. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Sebastião Marques Cardoso PAU DOS FERROS-RN 2020 1 2 A tese “O colonialismo extemporâneo de Angola, as ricas- donas, de Isabel Valadão”, autoria de Eliana Pereira de Carvalho, foi submetida à Banca Examinadora, constituída pelo PPGL/UERN, como requisito parcial necessário à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Letras, outorgado pela Universidade do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte – UERN Tese defendida e aprovada em 21 de dezembro de 2020. BANCA EXAMINADORA Prof. Dr. Sebastião Marques Cardoso – UERN (Presidente) Prof. Dr. Sebastião Alves Teixeira Lopes – UFPI (1º Examinador) Prof. Dr. Douglas Rodrigues de Sousa – UEMA (2º Examinador) Profa. Dra. Maria Aparecida da Costa – UERN (3ª Examinador) Profa. Dra. Concísia Lopes dos Santos – UERN (4ª Examinador) Prof. Dr. Tito Matias Ferreira Júnior – IFRN (Suplente) Prof. Dr. Manoel Freire Rodrigues – UERN (Suplente) PAU DOS FERROS 2020 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da UERN.