THE LANGUAGE and SYMBOLISM of CONQUEST in IRELAND, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flynn, R. 'Tackling the Directive: Television Without Frontiers and Irish Soccer.' in Trends in Communication Vol. 12, 2/3

Flynn, R. ‘Tackling the Directive: Television Without Frontiers and Irish soccer.’ in Trends in Communication Vol. 12, 2/3, pp. 131 - 152. Abstract With the liberalisation of European Broadcasting from the 1980s and the early identification by new commercial channels of sporting events as key content to encourage viewing/subscription the relationship between sports and media organisations has inevitably become closer and more lucrative. However with the amendment of the Television Without Frontiers directive in 1997 a new element - the state - entered the equation, rendering it all the more complex. This paper demonstrates the extent to which in the modern era sports journalism can only offer a truly comprehensive account of events by adopting approaches more commonly associated with business and political journalism. It does so by examining the biggest Irish “sports” story of 2002: not the Irish teams participation in the World Cup but the subsequent sale of broadcast rights for that team’s home games to BSkyB. The narrative throws light on the increasingly complex relationship between sport, commercial and public service media, and the state but also details an extremely novel application of the Television Without Frontiers directive by the Irish state. * * * * On July 5 2002, three weeks after the Republic of Ireland football team had returned from the World Cup in Asia, the Football Association of Ireland (FAI) announced that they had sold BSkyB exclusive live television rights to Republic of Ireland home internationals for the next four years. The statement went on to note that deferred coverage rights had been sold to TV3, Ireland’s only privately owned1 free-to-air commercial broadcaster. -

FE1 Lecturers

Our Lecturers Helen O’Sullivan BA History and Sociology, Diploma in Legal Studies (Kings Inns), BL Helen is a graduate of both University College Dublin and the Honorable Society of the Kings Inns. Having completed the Barrister-at-Law degree at the Honorable Society of the King’s Inns, she was called to the Bar in 2014. She practises predominantly in the area of Succession Law and property law. Helen also lectures succession law as part of the City Colleges Qualified Lawyers Transfer Test (QLTT) programme. Ciarán Lawlor BCL, LLM, BL Ciarán Lawlor is a practicing Barrister and an experienced legal educator. Ciarán graduated from University College Dublin with an Honours Degree in Law, and proceeded to study at the Honorable Society of the King’s Inns . He completed his studies at the King’s Inns and was called to the Irish Bar in 2005. He subsequently completed an LLM in European Law also at UCD, graduating with distinction. Prior to commencing practice at the Irish Bar, Ciarán interned with leading Irish law firm A&L Goodbody, and with Amnesty International (Ireland), and was an IRCHSS funded project assistant on the EU Law PhD project at UCD. His practice focuses on civil law, with an emphasis on contract and commercial litigation, debt-collection, defamation, personal injuries, and tort law generally. Ciarán has a broad experience of teaching law. He has been a Senior Tutor in UCD, and has lectured in tort law on the Graduate Diploma in Arbitration in UCD. Conor Duff LLB, BL Conor Duff is a graduate of Maynooth University (LL.B.); The Honorable Society of King’s Inns (B.L) and the Law Society of Ireland (Dip. -

Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland

Creating Citizens from Colonial Subjects: Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland Dr. Arlene Crampsie School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy University College Dublin ABSTRACT: Despite the incorporation of Ireland as a constituent component of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through the 1801 Act of Union, for much of the early part of the nineteenth century, British policy towards Ireland retained its colonial overtones. However, from the late 1860s a subtle shift began to occur as successive British governments attempted to pacify Irish claims for independence and transform the Irish population into active, peaceful, participating British citizens. This paper examines the role played by the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898 in affecting this transformation. The reform of local government enshrined in the act not only offered the Irish population a measure of democratic, representative, local self- government in the form of county, urban district, and rural district councils, but also brought Irish local government onto a par with that of the rest of the United Kingdom. Through the use of local and national archival sources, this paper seeks to illuminate a crucial period in Anglo-Irish colonial relations, when for a number of years, the Irish population at a local level, at least, were treated as equal imperial citizens who engaged with the state and actively operated as its locally based agents. “Increasingly in the nineteenth century the tentacles of the British Empire were stretching deep into the remote corners of the Irish countryside, bearing with them schools, barracks, dispensaries, post offices, and all the other paraphernalia of the … state.”1 Introduction he Act of Union of 1801 moved Ireland from the colonial periphery to the metropolitan core, incorporating the island as a constituent part of the imperial power of the United TKingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

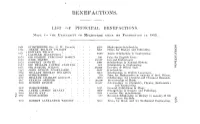

Benefactions

BENEFACTIONS. LIST (.iV PKilSTClTAL BENEFACTIONS. MAIM-: T<> TH.K UNIVKKSITY OK MELBOURNE SINOK ITS FOUNDATION IN 1S53. ISM SI.'IISCRIHEUS CSir. <i. W. IIUMIKX) ,tS.r'C Shilki.'spi.-arc Seln'Iai'ship. l,;7i IIENKV Tnl.MAN IrWUiHT fil 101' Rrizns for History and Education. -, l EHWARI1 WILSON" , '' ' "i LAC 11 LAN MACKINNON. ' 10(10 Avails Scholarship in Enu'itiL'iM-iii--. 1ST:; 'SIR CKllltliE l-'EIKilisr r.V HnWEN 1UII I'r-izu for English Essay. 1*7:; JOHN HASTIE .... I,s7:i OODI-'REY IK>\\ ITX Ill, till (IClli'l'lll KlllliiU'llltlllt 1S7:; Sill. WILLIAM l-'OSTKI! STAWELL 'WOO Scholarships hi N'lilnral History, ISS7:". SIK. SAMUEL WlLS'iN ririi'i Scholarship hi lOnirin^i'rin^. !*>:; JOHN IUXSON WYSELASKIE - Hfr.llllir Erection nf Wilson Hull. is.vl WILLIAM THOMAS Mi 1I.I.IS1 IX xnlO Scholarships 1,<S1 StinSCRIIiERS .... rilluli Scholarships in .Modern Luii^iiiiffcs. P-S7 WILLIAM CHARLES EEliXnT - l.Mi I'ri/n for- Mathematics in memory nf I'rof. Wilson, ls>7 l-'liANCIS ORMOMIl -.alilo Scholarships for Physical and Chemical .Re.Keareli. isrni Hi'rHERT lil.XSIlN L'II.OOII I'iorcssorship of Music. 10,s:r7 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics IS'" SLUSCIUDERS .... .•mil (-'.nuiiiL'i-'i'iii^. ,ri-17 Onnnnd Kxhihitions in Musi'-. IS!U JAMES CEIIKCiE HEAXEY :{!li.m Scholarships in Snrjrevy und Pathology. l.V.M I.1AVH1 KAY o7(;l .Caroline Kuy Scholarsnips, 1WI7 SUHSOlill.iERS 7;•'l,-l Research Scholarship in biology in memory of Sir .lames MacHain, I'.mj ROMERT ALEXANDER WHICHT lin'.o Prizes lor Music and ffir Mechanical Kn'.riiicel-inir. -

The National Conference on the Occasion of the 850Th Anniversary of the Anglo-Norman Invasion of Ireland

Invasion 1169 The National Conference on the occasion of the 850th Anniversary of the Anglo-Norman Invasion of Ireland The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife’, Daniel Maclise, c.1854, © National Gallery of Ireland. Speakers include: David Bates (East Anglia) * Elizabeth Boyle (Maynooth) * Keith Busby (Wisconsin-Madison) * Bruce Campbell (QUB) * Denis Casey (Maynooth) * Peter Crooks (Trinity) * Ruairí Cullen * Seán Duffy (Trinity) * Marie Therese Flanagan (QUB) * Robin Frame (Durham) * Jeremy Hill * Rachel Moss (Trinity) * Ronan Mulhaire (Trinity) * Máire Ní Mhaonaigh (Cambridge) * Colmán Ó Clabaigh (Glenstal Abbey) * Ruairí Ó hUiginn (DIAS) * Linzi Simpson * Thomas W. Smith (Leeds) * Michael Staunton (UCD) * Colin Veach (Hull) * Nicholas Vincent (East Anglia) * Caoimhe Whelan (Trinity) Thursday 2nd to Saturday 4th May 2019 Edmund Burke Theatre (Arts Building), Trinity College Dublin ADMISSION FREE • ALL WELCOME Register at: https://www.tcd.ie/medieval-history/invasion1169/ For information: [email protected] The 3rd Trinity Medieval Ireland Symposium The 3rd Trinity Medieval Ireland Symposium Ireland Medieval Trinity 3rd The www.tcd.ie/medieval-history/invasion1169/ Registration and information: information: and Registration ALL WELCOME ALL • FREE ADMISSION Trinity College Dublin College Trinity significance of 1169 in Ireland’s historical development. historical Ireland’s in 1169 of significance (Arts Building) Building) (Arts (or perhaps reconfirming) myths, and shedding new light on the the on light new shedding and myths, reconfirming) perhaps (or Edmund Burke Theatre Theatre Burke Edmund raising public awareness of this important anniversary, dispelling dispelling anniversary, important this of awareness public raising 4th May 2019 May 4th 2nd to Saturday Saturday to Thursday bring the Anglo-Norman invasion into the realm of public discourse, discourse, public of realm the into invasion Anglo-Norman the bring the light of the latest cutting-edge research. -

Going Against the Flow: Sinn Féin´S Unusual Hungarian `Roots´

The International History Review, 2015 Vol. 37, No. 1, 41–58, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.879913 Going Against the Flow: Sinn Fein’s Unusual Hungarian ‘Roots’ David G. Haglund* and Umut Korkut Can states as well as non-state political ‘actors’ learn from the history of cognate entities elsewhere in time and space, and if so how and when does this policy knowledge get ‘transferred’ across international borders? This article deals with this question, addressing a short-lived Hungarian ‘tutorial’ that, during the early twentieth century, certain policy elites in Ireland imagined might have great applicability to the political transformation of the Emerald Isle, in effect ushering in an era of political autonomy from the United Kingdom, and doing so via a ‘third way’ that skirted both the Scylla of parliamentary formulations aimed at securing ‘home rule’ for Ireland and the Charybdis of revolutionary violence. In the political agenda of Sinn Fein during its first decade of existence, Hungary loomed as a desirable political model for Ireland, with the party’s leading intellectual, Arthur Griffith, insisting that the means by which Hungary had achieved autonomy within the Hapsburg Empire in 1867 could also serve as the means for securing Ireland’s own autonomy in the first decades of the twentieth century. This article explores what policy initiatives Arthur Griffith thought he saw in the Hungarian experience that were worthy of being ‘transferred’ to the Irish situation. Keywords: Ireland; Hungary; Sinn Fein; home rule; Ausgleich of 1867; policy transfer; Arthur Griffith I. Introduction: the Hungarian tutorial To those who have followed the fortunes and misfortunes of Sinn Fein in recent dec- ades, it must seem the strangest of all pairings, our linking of a party associated now- adays mainly, if not exclusively, with the Northern Ireland question to a small country in the centre of Europe, Hungary. -

To Plant and Improve: Justifying the Consolidation of Tudor and Stuart Rule in Ireland, 1509 to 1625

To Plant and Improve: Justifying the Consolidation of Tudor and Stuart Rule in Ireland, 1509 to 1625 Samantha Watson A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Languages Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences September 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Watson First name: Samantha Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: School of Humanities and Languages Faculty: Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Title: To plant and improve: justifying the consolidation of Tudor and Stuart rule in Ireland, 1509 to 1625. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis aims to examine the ideologies employed in justifying English conquest and plantation of Ireland between 1509 and 1625. It adopts the methodology of a contextualist intellectual history, which situates the sources within the intellectual and material world, and in relation to the publically approved paradigms, available to the authors. The thesis encompasses a range of source material - correspondence, policy papers and published tracts - from major and minor figures in government and undertakers of colonisation schemes. The source material will be examined with respect to the major upheavals in intellectual culture in late medieval and early modern England and, in particular, the impact of major pan- European movements, the Protestant Reformation and the Renaissance. Focussing on the ethics associated with the spread of Renaissance humanism and Calvinist Protestantism, it explores socio-political ideas in England and examines the ways that these ideas were expressed in relation to Ireland. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

Article the Empire Strikes Back: Brexit, the Irish Peace Process, and The

ARTICLE THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK: BREXIT, THE IRISH PEACE PROCESS, AND THE LIMITATIONS OF LAW Kieran McEvoy, Anna Bryson, & Amanda Kramer* I. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................610 II. BREXIT, EMPIRE NOSTALGIA, AND THE PEACE PROCESS .......................................................................615 III. ANGLO-IRISH RELATIONS AND THE EUROPEAN UNION ...........................................................................624 IV. THE EU AND THE NORTHERN IRELAND PEACE PROCESS .......................................................................633 V. BREXIT, POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN NORTHERN IRELAND ....637 VI. BREXIT AND THE “MAINSTREAMING” OF IRISH REUNIFICATION .........................................................643 VII. BREXIT, POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND THE GOVERNANCE OF SECURITY ..................................646 VIII. CONCLUSION: BREXIT AND THE LIMITATIONS OF LAW ...............................................................................657 * The Authors are respectively Professor of Law and Transitional Justice, Senior Lecturer and Lecturer in Law, Queens University Belfast. We would like to acknowledge the comments and advice of a number of colleagues including Colin Harvey, Brian Gormally, Daniel Holder, Rory O’Connell, Gordon Anthony, John Morison, and Chris McCrudden. We would like to thank Alina Utrata, Kevin Hearty, Ashleigh McFeeters, and Órlaith McEvoy for their research assistance. As is detailed below, we would also like to thank the Economic -

FLAG of IRELAND - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF IRELAND - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia The Easter Rising Rebels originally adopted the modern green-white-orange tricolour flag. Technical Specification Adopted: Officially 1937 (unofficial 1916 to 1922) Proportion: 1:2 Design: A green, white and orange vertical tricolour. Colours: PMS – Green: 347, Orange: 151 CMYK – Green: 100% Cyan, 0% Magenta, 100% Yellow, 45% Black; Orange: 0% Cyan, 100% Magenta 100% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History The first historical Flag was a banner of the Lordship of Ireland under the rule of the King of England between 1177 and 1542. When the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 made Henry VII the king of Ireland the flag became the Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland, a blue field featuring a gold harp with silver strings. The Banner of the Lordship of Ireland The Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland (1177 – 1541) (1542 – 1801) When Ireland joined with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, the flag was replaced with the Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. This was flag of the United Kingdom defaced with the Coat of Arms of Ireland. During this time the Saint Patrick’s flag was also added to the British flag and was unofficially used to represent Northern Ireland. The Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland The Cross of Saint Patrick (1801 – 1922) The modern day green-white-orange tricolour flag was originally used by the Easter Rising rebels in 1916. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page