CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION to the STUDY 1.1 the Changing Vitality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of the Actual State of the Coal Related Research And

- f, ATfH ,4,01 LiX received AUG 1 3 @98 OSTI ¥J$10¥ 3 M M0J,8#3N OF THIS DOCUMENT IS UNllMiTED FOREIGN SALES PROHIBITED DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. o i EA03-;i/vf-fyD^o:^ %BMJ 1 9 9 7 Jnx 7 -i ms#### s 7-2 ^7%4b 3-1 #f-m%c;:B$ 7 -3 dc^amcm# 3 -2 7 -4 3-3 7 -5 C i^o-tx 3 — 3 — 1 IS JUfitia 8 j&% 3—3 — 2 #i# 8 -i mmm 3 -3-3 &mm# 9 gsm#%m 3-3-4 a#<k. i o wm# 4 Ursa 1 1 l»an s 12 #m. 6 5^#-E n-X U ■y--3-K&mir'bMH> btifcr-^M-f&.(DMMfcfe o £ /c, — S x|;l'f-f-^<-X>/XrAi'f)7HXT^tto d ti t> © ft§i:o ^ t. LT(i> #:c$A/:F--#####-&;%;&## NEDom#t>^- t 170-6028 3 XB1#1^ SIS 03-3987-9412 FAX 03-3987-8539 \s — 9 rMI VENAJ ................................... Bill s! M•##%## gj^ 07K^<k#e#(c# a m TCi^fc 15 h y 7 > h 0^:% iam0m%)....... • 7k x 5 y - — 1 — (it) x^;i/^' — %# s&x ezR (it) X $ ;l/f — (it) x * /l/f — T v y ,1/f - 9 y h - ^ ic j: % s iffcf IE y X T A - (PWM) 0#Ax - 2 - (#) (C WM) OX? 7-f Kixy^^-±®@NOxYI:#^: # 0E% V If ~z. it lx 5^ ® ic j: % ae<b a ^ib{@ ®## (C ck % i@5y 5%* 9 ^b — 3 — 7? y (c j; iS(cjo(f 6 7 y + y d^/iz h # y 3 — h $* — Jl'MM '> 7 T- j:6W 18 o i-' fc5g a x -fbSJS — 4 — C O 2E<b@JR5j^S^M H D ^ ^ A o#^s y a J^ /f % /< — • SIM 3 7° D -fe .y '> y y 7 ? V ^ ^ :7 r 'i #{b,3 y ^7 V — h ®MM -f-0 S OZ^'X^bM^^fCc I't RErMSM#'x^b^ck & S 0 2if x^ 6 $^*"x<bB|©Ty!/* V A#®3%# — 5 — f-7 (%%) 'SHffijT? $ y — y ££ 5 7 y ^ ^ i~i L f: n - vi, ^ y - =. -

Hong Kong Summer Fun

Hong Kong Summer Fun Hong Kong Summer Fun True to its name, the Hong Kong Summer Fun “Shop.Eat.Play” (HKSF) campaign delighted even the most discerning visitors with all the amazing surprises one could ask for in a holiday. Visitors were treated to a range of attractive packages, lucky draws and citywide rewards we solicited through vigorous trade cooperation. Together with our comprehensive public relations and consumer communications initiatives, the summer promotion was an excellent demonstration of the industry’s determination to power up Hong Kong’s tourism. Developing Pre-Trip Awareness A great vacation starts with well-thought-out planning, and we understand that everyone could do with a bit of inspiration to make the most out of their precious time off. Employing a 360-degree communication plan allowed us to reach consumers worldwide as early as their research stage to get them interested in Hong Kong’s summer attractions before they become overwhelmed with choices. The purpose of the appealing offers we put together was to make their decision-making easier. Large-scale consumer communications campaign New “Shop.Eat.Play” TV commercial This 30-second video, showcasing some of Hong Kong’s finest shopping, eating and playing experiences during the HKSF campaign, was broadcast on Discovery Networks, Fox, Star Movies, CNN, BBC World News, National Geographic, and other major local channels. Digital promotions We extended our reach to a wider audience through key digital platforms, such as YouTube, Google and our own website and social media accounts. We ran a daily social media contest for a trip to Hong Kong to build up excitement during the countdown to the launch of the HKSF campaign. -

2017 a Decade of Decisions

Complaints Bureau Orders 2007- 2017 A Decade of Decisions Communications and Multimedia Content Forum of Malaysia Forum Kandungan Komunikasi dan Multimedia Malaysia Published by Communications and Multimedia Content Forum of Malaysia (CMCF) March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Communications and Multimedia Content Forum of Malaysia (CMCF). E ISBN: All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or web distribution, without the written permission of the publisher. EDITOR Dr. Manjit Kaur Ludher While every effort is made to ensure that accurate information is disseminated through this publication, CMCF makes no representation about the content and suitability of this information for any purpose. CMCF is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the results obtained from the use of the information in this publication. In no event will CMCF be liable for any consequential, indirect, special or any damages whatsoever arising in connection with the use or reliance on this information. PUBLISHER Communications and Multimedia Content Forum of Malaysia (CMCF) Forum Kandungan Komunikasi dan Multimedia Malaysia Unit 1206, Block B, Pusat Dagangan Phileo Damansara 1 9 Jalan 16/11, Off Jalan Damansara, 46350 Petaling Jaya Selangor Darul Ehsan, MALAYSIA Website: www.cmcf.my This book is dedicated in loving memory of Communications and Multimedia Content Forum’s founding Chairman Y. Bhg. Dato’ Tony Lee CONTENTS Foreword by Chairman, CMCF…………………………………………………………………………………. -

Jo Girard Juillet 2007 2041

Année Ville Source Diffusion Frequence Titre Archive Contenu Date Diffusion 1896? Archive N/A Extrait marconi 1924 Archive N/A Broadcasting tests PP Eckersley: re-recording 14/05/24 1924 Archive N/A Open speech by King-George V 1928 Archive N/A Allocution-Charles Lindbergh 11/04/28 1929 Archive N/A Radio Hongroise en 1929 1930's Archive N/A Radio Normandie programme en anglais 1933 Archive N/A Annonce horloge "19h58mn40sec…" 1933 Archive N/A Discours Hitler aux sa et ss 30/01/33 1935 Bruxelles RTBF Funérailles de la reine Astrid 1935 Londres BBC Round London at night, quaint introduction to a program on London by Robert Dougall 14/12/35 1935 Londres BBC The Great Family, Christmas message The Great Family, (25.12.35) 25/12/35 Christmas message. 1935 Guglielmo-Marconi 6/12/35 1936 Londres BBC Death of King Georges V announcement by the then Dir of the BBC John Reith 20/01/36 1936 Paris Radio Cité Identification de la station 1937 Londres(?) A rechercher Extract One, Thomas Woodrooffe was drunk when he did this commentary at the Spit head royal naval 20/05/37 review 1937 Paris Radio Cité Carillon de Radio Cité 1939 Radio Meditérranée je reçois bien volontiers les vœux de Radio Méditerranée… Edouard Branly "je reçois bien volontiers les vœux de Radio Méditerranée…" 1939 Archive N/A Annonce début 2eme guerre mondiale. 1939 Archive N/A Appel radio US crise polonaise août-39 1939 Archive N/A Interview Abbé Joseph Bovet 1939 Archive N/A Reportage de F Poulin La descente des Alpes à Hauteville 1939 Archive N/A NewsWar39: Soviet Clean mono 1940 Archive N/A Benito Mussolini Discours public. -

MALAYSIAN MUSIC and SOCIAL COHESION: CONTEMPORARY RESPONSES to POPULAR PATRIOTIC SONGS from the 1950S – 1990S

JATI-Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Volume 25(1), June 2020, 191-209 ISSN 1823-4127/e-ISSN 2600-8653 MALAYSIAN MUSIC AND SOCIAL COHESION: CONTEMPORARY RESPONSES TO POPULAR PATRIOTIC SONGS FROM THE 1950s – 1990s Shazlin A. Hamzah* & Adil Johan (* First author) Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA) Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia ([email protected], [email protected]) Doi: https://doi.org/10.22452/jati.vol25no1.10 Abstract Upon its independence in 1957, Malaysia was in the process of becoming a modern nation and therefore required modern totems to bind together its diverse population. Malaysia’s postcolonial plural society would be brought under the imagined ‘nation-of-intent’ of the government of the day (Shamsul A. B., 2001). Music in the form of the national anthem and patriotic songs were and remained essential components of these totems; mobilised by the state to foster a sense of national cohesion and collective identity. These songs are popular and accepted by Malaysian citizens from diverse backgrounds as a part of their national identity, and such affinities are supported by the songs’ repeated broadcast and consumption on national radio, television and social media platforms. For this study, several focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted in Kuching, Kota Kinabalu and the Klang Valley. This research intends to observe and analyse whether selected popular patriotic songs in Malaysia, composed and written between the 1960s to 2000 could promote and harness a sense of collective identity and belonging amongst Malaysians. There exists an evident lacuna in the study of the responses and attitudes of Malaysians, specifically as music listeners and consumers of popular patriotic songs. -

Media-Release-Music--Monuments

MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release SINGAPOREANS TO ENJOY DIGITAL MUSIC PERFORMANCES AT OUR HISTORIC NATIONAL MONUMENTS New series of music videos to inspire greater appreciation for Singapore’s built heritage and homegrown talents Singapore, 24 September 2020 – From songs waxing lyrical about the moon, to rearrangements of popular festive tunes, Singaporeans can immerse in a visual and auditory experience at our historic National Monuments through an all new Music At Monuments – National Heritage Board x Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre (NHB x SCCC) digital music performance series. From now till December 2020, NHB’s Preservation of Sites and Monuments division and SCCC will be jointly rolling out a line-up of four music videos featuring Singapore talents, all produced at our National Monuments. They will allow everyone to view these icons of our built heritage in a different light, while showcasing the diverse talents of our local musicians. 2 Alvin Tan, Deputy Chief Executive (Policy & Community), NHB, said: “We came up with the idea of staging musical showcases at our monuments because we wanted to combine the magic of musical performances with the ambience of historical settings to create a new monumental experience for our audiences. At the same time, these digital showcases are part of NHB’s efforts to create digital content to maintain access to arts and culture, and serve as a source of revenue for our local artistes and arts groups.” 3 The four National Monuments that will take centre stage in this music performance series are the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM), Goodwood Park Hotel, Jurong Town Hall and Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall (SYSNMH). -

Infocomm Clubs

ANNEX A: FACT SHEET ON INFOCOMM CLUBS Infocomm Clubs – What it is • Infocomm Clubs are part of IDA’s larger Student Infocomm Outreach programme under its S$120m Infocomm Manpower Development Roadmap. A joint effort by IDA and industry partners, with support from the Ministry of Education (MOE), the Infocomm Clubs aim to: - Excite students about the possibilities of infocomm in a fun way - Expand students’ creative and entrepreneurial spirit through application of infocomm in school and society - Work with infocomm industry partners so that the private sector can play a proactive role in developing the youths in schools • Infocomm Clubs are targeted at primary, secondary school and junior college students. The initiative started in November 2005. • Activities in Infocomm Clubs are aligned with MOE’s Co-Curricular Activities (CCA) framework1 where students earn CCA points through participation in the Clubs. The Club activities include project work, competitions, and cross-school collaborations. Other benefits of Club participation include potential credit exemption and/ or direct admission into infocomm courses at IHLs. Students also enjoy mentorship opportunities and certification by industry partners when they complete their membership. • For a start, Infocomm Clubs boast of industry partners such as Adobe, Apple, Cisco, Nanyang Polytechnic, Novell, SingTel and Temasek Polytechnic, offering structured curriculum in new Infocomm growth areas such as Animation, 3D Animation, Video Software, Web Publishing, Security and Networking Software, Mobile Content, Software and Applications, Security, Games Development and Digital Media. New Additions to the Infocomm Clubs A) Infocomm Club Ambassador Programme • The Ambassador Programme has been created to allow selected students to play a larger role in the Infocomm Clubs Programme. -

Annex G November 2011

Annex G November 2011 FACT SHEET Enhanced Infocomm Club Programme The Infocomm Club Programme, first introduced in 2005, is a Co-Curricular Activity (CCA) for primary, secondary and junior college students. The Infocomm Club Programme is aligned with with Strategy 3 of the Infocomm Manpower Development Roadmap v2.0 (“MDEV 2.0”) to “Generate Curiosity, Interest and Passion” for infocomm. The programme aims to provide students the opportunity to pursue their interest in infocomm, acquire infocomm skills and be engaged in the larger infocomm student community. Highlights of key achievements • 270 Infocomm Clubs with about 15,000 members in Primary Schools, Secondary Schools, Junior Colleges and Integrated Programme Schools. • Since 2006, 62 Youth Infocomm Ambassadors have been appointed. • 75% of Infocomm Club Students agreed that they are satisfied with the Infocomm Clubs Programme [Source: Annual Infocomm Clubs Survey 2010]. • 73% of students developed an interest in Infocomm through the Infocomm Club [Source: Annual Infocomm Clubs Survey 2010]. Programme Description Activities in Infocomm Clubs are aligned with the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) Co- Curricular Activities (CCA) framework1 where students earn CCA points through participation in the clubs. Club activities include project work, competitions, and cross-school collaborations. Other benefits of Club participation include potential credit exemption and/or direct admission into infocomm courses at Institutes of Higher Learning and consideration for IDA’s National Infocomm and Integrated Infocomm Scholarships. Students also enjoy mentorship opportunities and certification by industry partners when they complete their membership. In 2010, IDA rolled out the Enhanced Infocomm Clubs Programme (“EICP”). The aim of this enhancement to the Infocomm Clubs Programme is to: 1 MOE CCA framework for LEAPS (Leadership, Enrichment, Achievement, Participation and Service). -

Agenda Public Meeting Borough of Montvale

AGENDA PUBLICMEETING BOROUGHOF MONTVALE Mayor and Council Meeting February 11, 2020 Budget Meeting to Commence 6:00 P.M. Meeting to Commence 7:30 P.M. (No Closed/Executive Session) ROLL CALL: Councilmember Arendacs Councilmember Lane Councilmember Curry Councilmember Roche Councilmember Koelling Councilmember Russo-Vogelsang ORDINANCES: None. MEETING OPEN TO PUBLIC: Agenda Items Only MEETING CLOSED TO PUBLIC: Agenda Items Only MINUTES: January 28, 2020 MINUTES CLOSED/EXECUTIVE SESSION: None. RESOLUTIONS: RESOLUTIONS: (CONSENT AGENDA*) *All items listed on a consent agenda are considered to be routine and non-controversial by the Borough Council and will be approved by a motion, seconded and a roll call vote. There will be no separate discussion on these items unless a Council member(s) so request it, in which case the item will be removed from the Consent Agenda and considered in its normal sequence on the agenda. 52-2020 Authorize Refund of Recreation Program I Taekwon-Do 53-2020 Authorize Release Of Escrow/BCUW/Madeline Housing Partners, LLC / Bergen County United Way/Block 1606, Lots 6.0 & 6.02 54-2020 Resolution Adopting the Affirmative Fair Housing Marketing Plan for The Village Spring at Montvale 55-2020 Authorizing Resolution/2019 Bergen County Open Space Trust Fund/Memorial Drive Synthetic Turf Bocce Ball Courts BILLS: REPORT OF REVENUE: COMMITTEE REPORTS: ENGINEER'S REPORT: Andrew Hipolit Report/Update ATTORNEY REPORT: Joe Voytus, Esq. Report/Update UNFINISHED BUSINESS: None. NEW BUSINESS: a. Recommendation Increase In LOSAP Tri-Soro Volunteer Ambulance Corp./Borough of Park Ridge & Woodcliff Lake COMMUNICATION CORRESPONDENCE: None. MEETING OPEN TO THE PUBLIC: HEARING OF CITIZENS WHO WISH TO ADDRESS THE MAYOR AND COUNCIL: Upon recognition by the Mayor, the person shall proceed to the floor and give his/her name and address in an audible tone of voice for the records. -

Singapore's Fifth CEDAW Periodic Report

SINGAPORE’S FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT TO THE UN COMMITTEE FOR THE CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN October 2015 SINGAPORE’S FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT TO THE UN COMMITTEE FOR THE CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN Published in October 2015 MINISTRY OF SOCIAL AND FAMILY DEVELOPMENT REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior consent from the Ministry of Social and Family Development. ISBN 978-981-09-7872-3 FOREWORD 03 FOREWORD This year marks the 20th anniversary of Singapore’s accession to CEDAW. It is also the year Singapore celebrates the 50th year of our independence. In this significant year, Singapore is pleased to present its Fifth Periodic Report on the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). This Report covers the initiatives Singapore introduced from 2009 to 2015, to facilitate the progress of women. It also includes Singapore’s responses to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s (Committee) Concluding Comments (CEDAW/C/SGP/CO/4/Rev.1) at the 49th CEDAW session and recommendations by the Committee’s Rapporteur on follow-up in September 2014 (AA/follow-up/Singapore/58). New legislation and policies were introduced to improve the protection of and support for women in Singapore. These include the Protection from Harassment Act to enhance the protection of persons against harassment, and the Prevention of Human Trafficking Act to criminalise exploitation in the form of sex, labour and organ trafficking. -

Morning Mania Contest, Clubs, Am Fm Programs Gorly's Cafe & Russian Brewery

Guide MORNING MANIA CONTEST, CLUBS, AM FM PROGRAMS GORLY'S CAFE & RUSSIAN BREWERY DOWNTOWN 536 EAST 8TH STREET [213] 627 -4060 HOLLYWOOD: 1716 NORTH CAHUENGA [213] 463 -4060 OPEN 24 HOURS - LIVE MUSIC CONTENTS RADIO GUIDE Published by Radio Waves Publications Vol.1 No. 10 April 21 -May 11 1989 Local Listings Features For April 21 -May 11 11 Mon -Fri. Daily Dependables 28 Weekend Dependables AO DEPARTMENTS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 CLUB LIFE 4 L.A. RADIO AT A GLANCE 6 RADIO BUZZ 8 CROSS -A -IRON 14 MORNING MANIA BALLOT 15 WAR OF THE WAVES 26 SEXIEST VOICE WINNERS! 38 HOT AND FRESH TRACKS 48 FRAZE AT THE FLICKS 49 RADIO GUIDE Staff in repose: L -R LAST WORDS: TRAVELS WITH DAD 50 (from bottom) Tommi Lewis, Diane Moca, Phil Marino, Linda Valentine and Jodl Fuchs Cover: KQLZ'S (Michael) Scott Shannon by Mark Engbrecht Morning Mania Ballot -p. 15 And The Winners Are... -p.38 XTC Moves Up In Hot Tracks -p. 48 PUBLISHER ADVERTISING SALES Philip J. Marino Lourl Brogdon, Patricia Diggs EDITORIAL DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Tommi Lewis Ruth Drizen, Tracey Goldberg, Bob King, Gary Moskowi z, Craig Rosen, Mark Rowland, Ilene Segalove, Jeff Silberman ART DIRECTOR Paul Bob CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Mark Engbrecht, ASSISTANT EDITOR Michael Quarterman, Diane Moca Rubble 'RF' Taylor EDITORIAL ASSISTANT BUSINESS MANAGER Jodi Fuchs Jeffrey Lewis; Anna Tenaglia, Assistant RADIO GUIDE Magazine Is published by RADIO WAVES PUBLICATIONS, Inc., 3307 -A Plco Blvd., Santa Monica, CA. 90405. (213) 828 -2268 FAX (213) 453 -0865 Subscription price; $16 for one year. For display advertising, call (213) 828 -2268 Submissions are welcomed. -

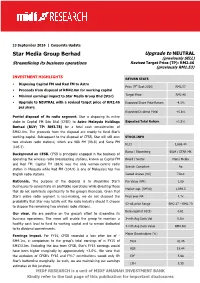

Star Media Group Berhad Upgrade to NEUTRAL (Previously SELL) Streamlining Its Business Operations Revised Target Price (TP): RM2.46

13 September 2016 | Corporate Update Star Media Group Berhad Upgrade to NEUTRAL (previously SELL) Streamlining its business operations Revised Target Price (TP): RM2.46 (previously RM1.53) INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS RETURN STATS • Disposing Capital FM and Red FM to Astro Price (9th Sept 2016) RM2.57 • Proceeds from disposal of RM42.0m for working capital • Minimal earnings impact to Star Media Group Bhd (Star) Target Price RM2.46 • Upgrade to NEUTRAL with a revised target price of RM2.46 Expected Share Price Return -4.3% per share Expected Dividend Yield +5.8% Partial disposal of its radio segment. Star is disposing its entire stake in Capital FM Sdn Bhd (CFSB) to Astro Malaysia Holdings Expected Total Return +1.5% Berhad (BUY; TP: RM3.78) for a total cash consideration of RM42.0m. The proceeds from the disposal are mainly to fund Star’s working capital. Subsequent to the disposal of CFSB, Star will still own STOCK INFO two wireless radio stations, which are 988 FM (98.8) and Suria FM KLCI 1,686.44 (105.3). Bursa / Bloomberg 6084 / STAR MK Background on CFSB. CFSB is principally engaged in the business of operating the wireless radio broadcasting stations, known as Capital FM Board / Sector Main/ Media and Red FM. Capital FM (88.9) was the only women-centric radio Syariah Compliant No station in Malaysia while Red FM (104.9) is one of Malaysia’s top five English radio stations. Issued shares (mil) 738.0 Rationale. The purpose of the disposal is to streamline Star’s Par Value (RM) 1.00 businesses to concentrate on profitable operations while divesting those Market cap.