Role of Caste in Migration: Some Observations from Beed District, Maharashtra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YES BANK LTD.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN Ground floor & First Arpan AND floor, Survey No Basak - NICOBAR 104/1/2, Junglighat, 098301299 ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Port Blair - 744103. PORT BLAIR YESB0000448 04 Ground Floor, 13-3- Ravindra 92/A1 Tilak Road Maley- ANDHRA Tirupati, Andhra 918374297 PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI, AP Pradesh 517501 TIRUPATI YESB0000485 779 Ground Floor, Satya Akarsha, T. S. No. 2/5, Door no. 5-87-32, Lakshmipuram Main Road, Guntur, Andhra ANDHRA Pradesh. PIN – 996691199 PRADESH GUNTUR Guntur 522007 GUNTUR YESB0000587 9 Ravindra 1ST FLOOR, 5 4 736, Kumar NAMPALLY STATION Makey- ANDHRA ROAD,ABIDS, HYDERABA 837429777 PRADESH HYDERABAD ABIDS HYDERABAD, D YESB0000424 9 MR. PLOT NO.18 SRI SHANKER KRUPA MARKET CHANDRA AGRASEN COOP MALAKPET REDDY - ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 64596229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD MALAKPET 500036 D YESB0ACUB02 4550347 21-1-761,PATEL MRS. AGRASEN COOP MARKET RENU ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA KEDIA - PRADESH HYDERABAD RIKABGUNJ 500002 D YESB0ACUB03 24563981 2-4-78/1/A GROUND FLOOR ARORA MR. AGRASEN COOP TOWERS M G ROAD GOPAL ANDHRA URBAN BANK SECUNDERABAD - HYDERABA BIRLA - PRADESH HYDERABAD SECUNDRABAD 500003 D YESB0ACUB04 64547070 MR. 15-2-391/392/1 ANAND AGRASEN COOP SIDDIAMBER AGARWAL - ANDHRA URBAN BANK BAZAR,HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 24736229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD SIDDIAMBER 500012 D YESB0ACUB01 4650290 AP RAJA MAHESHWARI 7 1 70 DHARAM ANDHRA BANK KARAN ROAD HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD AMEERPET AMEERPET 500016 D YESB0APRAJ1 23742944 500144259 LADIES WELFARE AP RAJA CENTRE,BHEL ANDHRA MAHESHWARI TOWNSHIP,RC HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD BANK BHEL PURAM 502032 D YESB0APRAJ2 23026980 SHOP NO:G-1, DEV DHANUKA PRESTIGE, ROAD NO 12, BANJARA HILLS HYDERABAD ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABA PRADESH HYDERABAD BANJARA HILLS 500034 D YESB0000250 H NO. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

MSM Monograph-8.Qxd

Publications from Avahan in this series Avahan—The India AIDS Initiative: The Business of HIV Prevention at Scale Off the Beaten Track: Avahan’s Experience in the Business of HIV Prevention among India’s Long-Distance Truckers Use It or Lose It: How Avahan Used Data to Shape Its HIV Prevention Efforts in India Managing HIV Prevention from the Ground Up: Avahan’s Experience with Peer Led Outreach at Scale in India Peer Led Outreach at Scale: A Guide to Implementation The Power to Tackle Violence: Avahan’s Experience with Community Led Crisis Response in India Community Led Crisis Response Systems: A Guide to Implementation From Hills to Valleys: Avahan's HIV Prevention Program among Injecting Drug Users in Northeast India Treat and Prevent: Avahan’s Experience in Scaling Up STI Services to Groups at High Risk of HIV Infection in India Breaking Through Barriers: Avahan’s Scale-Up of HIV Prevention among High-Risk MSM and Transgenders in India Also available at: www.gatesfoundation.org/avahan BREAKING THROUGH BARRIERS: Avahan’s Scale-Up of HIV Prevention among High-Risk MSM and Transgenders in India This publication was commissioned by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in India. We thank all who have worked tirelessly in the design and implementation of Avahan. We also thank James Baer who assisted in the writing and production of this publication. Version 1, June 2010 Citation: Breaking Through Barriers: Avahan's Scale-Up of HIV Prevention among High-Risk MSM and Transgenders in India. New Delhi: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 2010. -

Ichthyofauna of Majalgaon Re District of Marathwada Region Ofauna Of

RESEARCHRESEARCH ARTICLE 20(60), June 1, 2014 ISSN 2278–5469 EISSN 2278–5450 Discovery Ichthyofauna of Majalgaon reservoir from beed district of Marathwada Region, Maharashtra State Pawar RT Dept. of Zoology, Majalgaon Arts, Science and Commerce College, Majalgaon, Dist. Beed, (M.S.), India, Email: [email protected], [email protected] Publication History Received: 17 March 2014 Accepted: 04 May 2014 Published: 1 June 2014 Citation Pawar RT. Ichthyofauna of Majalgaon reservoir from beed district of Marathwada Region, Maharashtra State. Discovery, 2014, 20(60), 7-11 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. ABSTRACT The present investigation was carried out to study the diversity of fishes of Majalgaon Reservoir from Beed district, Maharashtra state. The present work is carried out during the period December 2011 to November 2012. The fish diversity is represented by 42 fish species belonging to 29 genera, 15 families and 9 orders. Besides identification, the economic importance of fish species is also discussed. Key words: Fish diversity, Economic importance, Majalgaon Reservoir. 1. INTRODUCTION Fishes form one of the most important groups of vertebrates, influencing the aquatic ecosystem & life in various ways. Millions of human beings suffer from hunger and malnutrition. The fishes form a rich source of food and provide a meal to tide over the nutritional difficulties of man in addition to serving as an important item of human diet from time immemorial and are primarily caught for this purpose. Fish diet provides proteins, fat and vitamins A & D. -

Weekly Weather Report for Maharashtra

- Oादेिशक मौसम कĞL , कोलाबा , मुंबई 400 005 Regional Meteorological Centre, Mumbai – 400005 Weekly Weather Report for Maharashtra WEEKLY WEATHER REPORT DURING THE WEEK ENDING ON 20-11-2019 (14.11.2019 to 20.11.2019) CHIEF FEATURES: NIL DISTRICT WISE WEEKLY RAIN FALL DISTRIBUTION FOR THE WEEK ENDING ON 20.11.2019: Large Excess : NIL Excess : NIL Normal : NIL Deficient : NIL Large Deficient : NIL No Rain : Gadchiroli, Washim Bhandara Sangli, Gondia Kolhapur, Nagpur Wardha, Nashik, Hingoli. Parbhani, Osmanabad Amaraoti, Yeotmal South Goa Dhule Raigad, Sindhudurg Ratnagiri Sholapur, Aurangabad Satara, Nanded, Chandrapur Latur Pune, Beed Ahmednagar, Mumbai City, Akola, North Goa Jalna Jalgaon, Palghar, Mumbai Suburban, Thane, Nandurbar Buldhana. DNA : NIL. DISTRICT WISE SEASONAL RAINFALL DISTRIBUTION FOR THE SEASON ENDING 20 .11 .2019 Large Excess : Mumbai city, Ahmednagar, Thane, Satara, Sangli, Sholapur Raigad, Kolhapur Osmanabad, Latur, Nanded, Jalna, Jalgaon Hingoli. Palghar, South Goa, Dhule , Sindhudurg, Parbahni, Aurangabad, North Goa, Nashik, Mumbai Suburban, Washim. Buldhana, Beed ,Pune. Excess : Akola, Chandrapur, Nandurbar, Ratnagiri. Normal : Wardha Gadchiroli. Deficient : Amaraoti, Yeotmal, Nagpur Bhandara, Gondia. Large Deficient : NIL No Rain : NIL. DNA : NIL. CHIEF AMOUNTS OF RAINFALL IN CM. KONKAN & GOA 11/14/2019 to 11/20/2019 : NONE MADHYA MAHARASHTRA 11/14/2019 to 11/20/2019 : NONE MARATHWADA 11/14/2019 to 11/20/2019 : NONE VIDARBHA 11/14/2019 to 11/20/2019 : NONE [Type text] SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF RAINFALL : Meteorological -

Fact Sheets Fact Sheets

DistrictDistrict HIV/AIDSHIV/AIDS EpidemiologicalEpidemiological PrProfilesofiles developeddeveloped thrthroughough DataData TTriangulationriangulation FFACTACT SHEETSSHEETS MaharastraMaharastra National AIDS Control Organisation India’s voice against AIDS Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India 6th & 9th Floors, Chandralok Building, 36, Janpath, New Delhi - 110001 www.naco.gov.in VERSION 1.0 GOI/NACO/SIM/DEP/011214 Published with support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Cooperative Agreement No. 3U2GPS001955 implemented by FHI 360 District HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profiles developed through Data Triangulation FACT SHEETS Maharashtra National AIDS Control Organisation India’s voice against AIDS Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India 6th & 9th Floors, Chandralok Building, 36, Janpath, New Delhi - 110001 www.naco.gov.in December 2014 Dr. Ashok Kumar, M.D. F.I.S.C.D & F.I.P.H.A Dy. Director General Tele : 91-11-23731956 Fax : 91-11-23731746 E-mail : [email protected] FOREWORD The national response to HIV/AIDS in India over the last decade has yielded encouraging outcomes in terms of prevention and control of HIV. However, in recent years, while declining HIV trends are evident at the national level as well as in most of the States, some low prevalence and vulnerable States have shown rising trends, warranting focused prevention efforts in specific areas. The National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) is strongly evidence-based and evidence-driven. Based on evidence from ‘Triangulation of Data’ from multiple sources and giving due weightage to vulnerability, the organizational structure of NACP has been decentralized to identified districts for priority attention. The programme has been successful in creating a robust database on HIV/AIDS through the HIV Sentinel Surveillance system, monthly programme reporting data and various research studies. -

AP Reports 229 Black Fungus Cases in 1

VIJAYAWADA, SATURDAY, MAY 29, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 RNI No.APENG/2018/764698 Established 1864 Published From VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 193 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable www.dailypioneer.com New DNA vaccine for Covid-19 Raashi Khanna: Shooting abroad P DoT allocates spectrum P as India battled Covid P ’ effective in mice, hamsters 5 for 5G trials to telecom operators 8 was upsetting 12 In brief GST Council leaves tax rate on Delhi will begin AP reports 229 Black unlocking slowly from Monday, says Kejriwal Coronavirus vaccines unchanged n elhi will begin unlocking gradually fungus cases in 1 day PNS NEW DELHI from Monday, thanks to the efforts of the two crore people of The GST Council on Friday left D n the city which helped bring under PNS VIJAYAWADA taxes on Covid-19 vaccines and control the second wave, Chief medical supplies unchanged but Minister Arvind Kejriwal said. "In the The gross number of exempted duty on import of a med- past 24 hours, the positivity rate has Mucormycosis (Black fungus) cases icine used for treatment of black been around 1.5 per cent with only went up to 808 in Andhra Pradesh fungus. 1,100 new cases being reported. This on Friday with 229 cases being A group of ministers will delib- is the time to unlock lest people reported afresh in one day. erate on tax structure on the vac- escape corona only to die of hunger," “Lack of sufficient stock of med- cine and medical supplies, Finance Kejriwal said. -

Impact of Extreme Weather Events in Relation to Floods Over Maharashtra in Recent Years D

Vayu Mandal 43(2), 2017 Impact of Extreme Weather Events in relation to Floods over Maharashtra in Recent Years D. M. Rase, P. S. Narayanan and K. N. Mohan India Meteorological Department, Pune Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT About 400 million hectares of land in India are susceptible to floods of which about 30.8 million hectares have been protected by undertaking both structural and non-structural methods of flood control. On an average, in a year, about 8 million hectares are liable to flood. In India, about 1500 human lives are lost annually due to floods and heavy rains. On an average, about 10 million hectares of crop land is devastated in each year due to impact of flood. We cannot avoid natural hazards (like flood) and disasters, but can minimize their impact on environment by preparedness & planning. Study of extreme rainfall is essential for designing the water related structure, in Agriculture planning, in weather modification, water management, also in monitoring climate changes. Moreover, knowledge of spatial and temporal variability of extreme rainfall event is very much useful for the design of Dam and hydrological planning. In view of the above, to find the impact of extreme / heavy rainfall in Maharashtra, rainfall data for the period 1951 to 2015 for three subdivisions of Maharashtra viz. Madhya Maharashtra, Marathwada and Vidarbha have been utilized for the study. Trends in number of incidences of excess rainfall have been determined by using standard statistical methods and the results discussed. Casualties due to extreme rainfall have also been discussed. Incidences of natural hazards reports prepared by India Met. -

Indian Society of Engineering Geology

Indian Society of Engineering Geology Indian National Group of International Association of Engineering Geology and the Environment www.isegindia.org List of all Titles of Papers, Abstracts, Speeches, etc. (Published since the Society’s inception in 1965) November 2012 NOIDA Inaugural Edition (All Publications till November 2012) November 2012 For Reprints, write to: [email protected] (Handling Charges may apply) Compiled and Published By: Yogendra Deva Secretary, ISEG With assistance from: Dr Sushant Paikarai, Former Geologist, GSI Mugdha Patwardhan, ICCS Ltd. Ravi Kumar, ICCS Ltd. CONTENTS S.No. Theme Journal of ISEG Proceedings Engineering Special 4th IAEG Geology Publication Congress Page No. 1. Buildings 1 46 - 2. Construction Material 1 46 72 3. Dams 3 46 72 4. Drilling 9 52 73 5. Geophysics 9 52 73 6. Landslide 10 53 73 7. Mapping/ Logging 15 56 74 8. Miscellaneous 16 57 75 9. Powerhouse 28 64 85 10. Seismicity 30 66 85 11. Slopes 31 68 87 12. Speech/ Address 34 68 - 13. Testing 35 69 87 14. Tunnel 37 69 88 15. Underground Space 41 - - 16. Water Resources 42 71 - Notes: 1. Paper Titles under Themes have been arranged by Paper ID. 2. Search for Paper by Project Name, Author, Location, etc. is possible using standard PDF tools (Visit www.isegindia.org for PDF version). Journal of Engineering Geology BUILDINGS S.No.1/ Paper ID.JEGN.1: “Excessive settlement of a building founded on piles on a River bank”. ISEG Jour. Engg. Geol. Vol.1, No.1, Year 1966. Author(s): Brahma, S.P. S.No.2/ Paper ID.JEGN.209: “Geotechnical and ecologial parameters in the selection of buildings sites in hilly region”. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

District Survey Report for Latur District For

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR LATUR DISTRICT FOR A. SAND MINING OR RIVER BED MINING B. MINERALS OTHER THAN SAND MINING OR RIVER BED MINING (Revision 01) Prepared under A] Appendix –X of MoEFCC, GoI notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.1.2016 B] Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines C] MoEFCC, GoI notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25.07.2018 Index Sr. Description Page No. No. 1 District Survey Report for Sand Mining Or River Bed Mining 1-61 1.0 Introduction 02 Brief Introduction of Latur district 03 Salient Features ofLatur District 07 2.0 Overview of Mining Activity in the district 08 3.0 List of the Mining Leases in the district with Location, area 10 and period of validity Location of Sand Ghats along the Rivers in the district 14 4.0 Detail of Royalty/Revenue received in last three years from 15 Sand Scooping activity 5.0 Details of Production of Sand or Bajri or minor mineral in last 15 three Years 6.0 Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the 15 District Stream Flow Guage Map for rivers in Latur district 19 Siltation Map for rivers in Latur district 20 7.0 General Profile of the district 21 8.0 Land Utilization Pattern in the District : Forest, Agriculture, 24 Horticulture, Mining etc. 9.0 Physiography of the District 27 River Inventory of the district 28 Basin Map for Latur district is drawn as 29 Confluence Points for the rivers in the district 30 Rivers marked on toposheets 31 HFL Maps for rivers 38 L & Cross sections for rivers 42 10.0 Rain Fall Data for Latur district 46 11.00 Geology and Mineral Wealth 47 Geological Map -

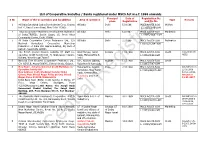

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi.