Who Let You in Here? Social Class, Sitcoms, and the New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hervey-Grimes-Resume.Pdf

Smith & Hervey/Grimes Talent Agency E85 Management Contact-Julie Smith Contact-Greg Strangis & Jacob Gallagher 3002 Midvale Ave. Suite 206 3406 W. Burbank Blvd Los Angeles, Ca 90034 Burbank, Ca 91505 310-475-2010 310-955-5835 C L I N T C A R M I C H A E L www.clintcarmichael.com SAG/AFTRA Eyes: Blue/Green Hair: Salt/Pepper HT: 6’4” FILM: Leads, Supporting: A KISS ON CANDY CANE LANE Dir: Stephanie McBain ZBURBS Dir: Greg Zekowski DEVIL’S GRAVEYARDS Dir: Doug Glover/ Pilgrim Studios STAR TREK: RENEGADES Dir: Tim Russ/Sky Conway Productions SHOOTING THE WARWICKS Dir: Adam Rifkin/D-Generate Prods KILLING HAPPY Dir: David Brandvik/Victorhouse Films DAMON (Award Winner) Dir: Nick Snyder/Damon Prods. BIG BAD Dir: Opie Cooper/Eyevox Prods. HEADSHOTS INC. Dir: Joel Hoffman/Quarterwater Ent. DISPATCH Dir: Steven Sprung/Dispatch Prod. THE HOUSE BUNNY Dir: Fred Wolf/Happy Madison Prod. THE OPEN DOOR (Award Winner) Dir: Doc Duhame/Ultimate Action NEW YORK TO MALIBU Dir: Danny Weisberg/Zero 2 Sixty MOVING PIECES (Award Winner) Dir: Chris Pulis/Froglegs Films SINBAD: BEYOND THE VEIL OF MISTS Dir: Alan Jacobs/Improvision Prods. TIME UNDER FIRE Dir: Tripp Reed/Royal Oaks Ent. MALEVOLENCE Dir: Belle Avery/Miramax COMMON GROUND Dir: Michael Donovan/Shadow Prod. NAKED GUN 33 1/3 Dir: Peter Segal/Paramount Pictures TELEVISION (partial list): WHY WOMEN KILL Co-Star Dir: Lucy Liu/CBS Television Studios ADAM RUINS EVERYTHING Guest Star Dir: Matt Pollack/TRU TV LA TO VEGAS Co-star Dir: Jim Hensz/FOX Studios LAW & ORDER TRUE CRIME Co-star Dir: Fred -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Face Attack in Italian Politics: Beppe Grillo's Insulting Epithets

1 Face attack in Italian politics: Beppe Grillo’s insulting epithets for other politicians1 ABSTRACT The second largest party in the Italian Parliament, the “5-Star Movement” is led by comedian-turned-politician Beppe Grillo. Grillo is well-known for a distinctive and often inflammatory rhetoric, which includes the regular use of humorous but insulting epithets for other politicians, such as Psiconano (“Psychodwarf”) for Silvio Berlusconi. This paper discusses a selection of epithets used by Grillo on his blog between 2008 and 2015 to refer to Berlusconi and three successive centre-left leaders. We account for the functions of the epithets in terms of Spencer-Oatey’s (2002, 2008) multi- level model of “face” and of Culpeper’s (2011) “entertaining” and “coercive” functions of impoliteness. We suggest that our study has implications for existing models of face and impoliteness and for an understanding of the evolving role of verbal aggression in Italian politics. 1. Introduction In the 2013 Italian general election, just under a quarter of the votes went to Il Movimento Cinque Stelle (The 5-Star Movement, or M5S) – a new political entity which had been founded four years before by comedian- turned-politician Beppe Grillo. One of the distinctive characteristics of Grillo’s language as leader of M5S is the coinage of humorous but insulting epithets for other politicians. Below is an extract from an online ‘political communiqué’ written by Grillo shortly after the 2008 general election: I partiti erano uno e bino, psiconano e Topo Gigio. PDL e PD-meno- elle […].(Grillo, n.d., Communiqué number 13) “The parties were one and two-in-one, psychodwarf and Gigio Mouse. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The Hunger Games: an Indictment of Reality Television

The Hunger Games: An Indictment of Reality Television An ELA Performance Task The Hunger Games and Reality Television Introductory Classroom Activity (30 minutes) Have students sit in small groups of about 4-5 people. Each group should have someone to record their discussion and someone who will report out orally for the group. Present on a projector the video clip drawing comparisons between The Hunger Games and shows currently on Reality TV: (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdmOwt77D2g) After watching the video clip, ask each group recorder to create two columns on a piece of paper. In one column, the group will list recent or current reality television shows that have similarities to the way reality television is portrayed in The Hunger Games. In the second column, list or explain some of those similarities. To clarify this assignment, ask the following two questions: 1. What are the rules that have been set up for The Hunger Games, particularly those that are intended to appeal to the television audience? 2. Are there any shows currently or recently on television that use similar rules or elements to draw a larger audience? Allow about 5 to 10 minutes for students to work in their small groups to complete their lists. Have students report out on their group work, starting with question #1. Repeat the report out process with question #2. Discuss as a large group the following questions: 1. The narrator in the video clip suggests that entertainments like The Hunger Games “desensitize us” to violence. How true do you think this is? 2. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Let Me Just Add That While the Piece in Newsweek Is Extremely Annoying

From: Michael Oppenheimer To: Eric Steig; Stephen H Schneider Cc: Gabi Hegerl; Mark B Boslough; [email protected]; Thomas Crowley; Dr. Krishna AchutaRao; Myles Allen; Natalia Andronova; Tim C Atkinson; Rick Anthes; Caspar Ammann; David C. Bader; Tim Barnett; Eric Barron; Graham" "Bench; Pat Berge; George Boer; Celine J. W. Bonfils; James A." "Bono; James Boyle; Ray Bradley; Robin Bravender; Keith Briffa; Wolfgang Brueggemann; Lisa Butler; Ken Caldeira; Peter Caldwell; Dan Cayan; Peter U. Clark; Amy Clement; Nancy Cole; William Collins; Tina Conrad; Curtis Covey; birte dar; Davies Trevor Prof; Jay Davis; Tomas Diaz De La Rubia; Andrew Dessler; Michael" "Dettinger; Phil Duffy; Paul J." "Ehlenbach; Kerry Emanuel; James Estes; Veronika" "Eyring; David Fahey; Chris Field; Peter Foukal; Melissa Free; Julio Friedmann; Bill Fulkerson; Inez Fung; Jeff Garberson; PETER GENT; Nathan Gillett; peter gleckler; Bill Goldstein; Hal Graboske; Tom Guilderson; Leopold Haimberger; Alex Hall; James Hansen; harvey; Klaus Hasselmann; Susan Joy Hassol; Isaac Held; Bob Hirschfeld; Jeremy Hobbs; Dr. Elisabeth A. Holland; Greg Holland; Brian Hoskins; mhughes; James Hurrell; Ken Jackson; c jakob; Gardar Johannesson; Philip D. Jones; Helen Kang; Thomas R Karl; David Karoly; Jeffrey Kiehl; Steve Klein; Knutti Reto; John Lanzante; [email protected]; Ron Lehman; John lewis; Steven A. "Lloyd (GSFC-610.2)[R S INFORMATION SYSTEMS INC]"; Jane Long; Janice Lough; mann; [email protected]; Linda Mearns; carl mears; Jerry Meehl; Jerry Melillo; George Miller; Norman Miller; Art Mirin; John FB" "Mitchell; Phil Mote; Neville Nicholls; Gerald R. North; Astrid E.J. Ogilvie; Stephanie Ohshita; Tim Osborn; Stu" "Ostro; j palutikof; Joyce Penner; Thomas C Peterson; Tom Phillips; David Pierce; [email protected]; V. -

Summer 2019 Calendar of Events

summer 2019 Calendar of events Hans Christian Andersen Music and lyrics by Frank Loesser Book and additional lyrics by Timothy Allen McDonald Directed by Rives Collins In this issue July 13–28 Ethel M. Barber Theater 2 The next big things Machinal by Sophie Treadwell 14 Student comedians keep ’em laughing Directed by Joanie Schultz 20 Comedy in the curriculum October 25–November 10 Josephine Louis Theater 24 Our community 28 Faculty focus Fun Home Book and lyrics by Lisa Kron 32 Alumni achievements Music by Jeanine Tesori Directed by Roger Ellis 36 In memory November 8–24 37 Communicating gratitude Ethel M. Barber Theater Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare Directed by Danielle Roos January 31–February 9 Josephine Louis Theater Information and tickets at communication.northwestern.edu/wirtz The Waa-Mu Show is vying for global design domination. The set design for the 88th annual production, For the Record, called for a massive 11-foot-diameter rotating globe suspended above the stage and wrapped in the masthead of the show’s fictional newspaper, the Chicago Offering. Northwestern’s set, scenery, and paint shops are located in the Virginia Wadsworth Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts, but Waa-Mu is performed in Cahn Auditorium. How to pull off such a planetary transplant? By deflating Earth. The globe began as a plain white (albeit custom-built) inflatable balloon, but after its initial multisection muslin wrap was created (to determine shrinkage), it was deflated, rigged, reinflated, motorized, map-designed, taped for a paint mask, primed, painted, and unpeeled to reveal computer-generated, to-scale continents. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

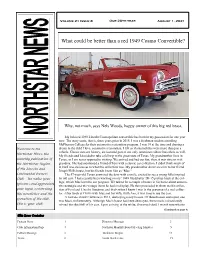

What Could Be Better Than a Red 1949 Cosmo Convertible?

Volume 21 Issue 8 Our 20th year August 1, 2021 What could be better than a red 1949 Cosmo Convertible? Why, not much, says Nels Woods, happy owner of this big red beast. My beloved 1949 Lincoln Cosmopolitan convertible has been in my possession for one year now. The story starts, that is, three years prior in 2018. I was a freshman student attending McPherson College for their automotive restoration program. I was 19 at the time and chasing a Welcome to the dream in the field I love, automotive restoration. I felt as if automobiles were more than just a vehicle. Classic cars are history, an essential part of not only American culture but others as well. Northstar News, the My friends and I decided to take a fall trip to the great state of Texas. My grandmother lives in monthly publication of Texas, so I am never opposed to visiting. We arrived and had our fun; then, it was time to visit the Northstar Region grandma. She had mentioned a friend of hers with a classic car collection. I didn't think much of it, but I was curious as to what this collection was. My grandmother drove me over to her friend of the Lincoln and Joseph Hill's house, but his friends knew him as "Mac." Continental Owners The 87-year-old Texan answered the door with a smile, excited to see a young fella inspired Club. We value your by old cars. I had recently been working on my ‘1949 Studebaker 2R-15 pickup truck at the col- lege, which Mac loved to see progress. -

For Immediate Release

‘ICE DREAMS’ CAST BIOS SHELLEY LONG (Harriet Clayton) – Shelley Long is an Emmy® and Golden Globe-winning actress. She began her career after attending Northwestern University by performing in small films and local theater, eventually becoming co-host and associate producer of a critically acclaimed Chicago magazine show “Sorting it Out,” for which she won three local Emmys. She eventually returned to her first passion, acting, and joined Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe. Shortly after, Long landed a role as barmaid Diane Chambers in the long-running NBC comedy “Cheers.” Long entertained audiences for five seasons, garnering an Emmy and two Golden Globes. She returned for the series’ top-rated finale and has reprised her “Cheers” role in guest appearances on NBC’s “Frasier,” one episode garnering an Emmy nomination. Long recently starred in a film short titled “A Couple of White Chicks at the Hairdresser,” and starred in a children’s DVD, “Mr. Vinegar and the Curse.” In 2006, Long starred in “Honeymoon With Mom” on Lifetime, and co-starred in the Hallmark Channel Valentine’s Day movie, “Falling In Love with the Girl Next Door.” She has made a number of guest TV appearances including “Boston Legal,” “Yes, Dear, “Joan of Arcadia,” “Complete Savages” and, most recently, ABC’s hit comedy “Modern Family.” Long was seen in the Robert Altman film “Dr. T and the Women” for Artisan Entertainment. Written by Anne Rapp and executive produced by Cindy Cowan and James McLindon, the film tells the story of a gynecologist, played by Richard Gere, who is battling a mid-life crisis.