Fans and the Making of History Philipp Dominik Keidl a Thesis in the Mel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

23 YEARS EXPLORING SCIENCE FICTION ^ GOLDFINGER s Jjr . Golden Girl: Tests RicklBerfnanJponders Er_ her mettle MimilMif-lM ]puTtism!i?i ff?™ § m I rifbrm The Mail Service Hold Mail Authorization Please stop mail for: Name Date to Stop Mail Address A. B. Please resume normal Please stop mail until I return. [~J I | undelivered delivery, and deliver all held I will pick up all here. mail. mail, on the date written Date to Resume Delivery Customer Signature Official Use Only Date Received Lot Number Clerk Delivery Route Number Carrier If option A is selected please fill out below: Date to Resume Delivery of Mail Note to Carrier: All undelivered mail has been picked up. Official Signature Only COMPLIMENTS OF THE STAR OCEAN GAME DEVEL0PER5. YOU'RE GOING TO BE AWHILE. bad there's Too no "indefinite date" box to check an impact on the course of the game. on those post office forms. Since you have no Even your emotions determine the fate of your idea when you'll be returning. Everything you do in this journey. You may choose to be romantically linked with game will have an impact on the way the journey ends. another character, or you may choose to remain friends. If it ever does. But no matter what, it will affect your path. And more You start on a quest that begins at the edge of the seriously, if a friend dies in battle, you'll feel incredible universe. And ends -well, that's entirely up to you. Every rage that will cause you to fight with even more furious single person you _ combat moves. -

Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1

Teaching Classical Languages Volume 10, Issue 2 Kopestonsky 71 Never Out of Style: Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1 Theodora B. Kopestonsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT Students often struggle to interpret Latin poetry. To combat the confusion, teachers can turn to a modern parallel (pop music) to assist their students in understanding ancient verse. Pop music is very familiar to most students, and they already trans- late its meaning unconsciously. Building upon what students already know, teach- ers can reframe their approach to poetry in a way that is more effective. This essay shows how to present the concept of meter (dactylic hexameter and elegy) and scansion using contemporary pop music, considers the notion of the constructed persona utilizing a modern musician, Taylor Swift, and then addresses the pattern of the love affair in Latin poetry and Taylor Swift’s music. To illustrate this ap- proach to connecting ancient poetry with modern music, the lyrics and music video from one song, Taylor Swift’s Blank Space (2014), are analyzed and compared to poems by Catullus. Finally, this essay offers instructions on how to create an as- signment employing pop music as a tool to teach poetry — a comparative analysis between a modern song and Latin poetry in the original or in translation. KEY WORDS Latin poetry, pedagogy, popular music, music videos, song lyrics, Taylor Swift INTRODUCTION When I assign Roman poetry to my classes at a large research university, I re- ceive a decidedly unenthusiastic response. For many students, their experience with poetry of any sort, let alone ancient Latin verse, has been fraught with frustration, apprehension, and confusion. -

Temple University Magazine Winter 2015

WINTER 2015 UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE TOXIC SHOCK A Temple researcher solves Naples’ cancer riddle. Joseph Labolito V. 22 STUDENTS BROTHERLY LOVE Temple students mentor college-age adults with intellectual disabilities through the Academy for Adult Learning. On campus, in Philadelphia and around the world, Owls spark change that matters. In this issue, students mentor adults with intellectual disabilities; the university offers a new admissions option; a dental program provides care to children in North Philadelphia; and a researcher exposes cancer rates in Italy. TEMPLETEMPLE 2 Letters 3 From the President 4 Campus Voice 5 News 14 Alumni News 37 Class Notes 52 The Last Word 72 143 73 144 74 145 75 146 76 147 77 148 78 149 79 150 80 151 81 152 82 153 83 154 84 155 85 156 86 157 87 158 88 159 89 160 90 161 91 162 92 163 93 164 94 165 95 166 96 167 97 168 98 169 99 170 100 171 16 10126 172 32 RESEARCH ALUMNI COMMUNITY IN THE LAND OF POISON AND FIRE TEST CASE FILLING A NEED A Temple cancer researcher from Naples, Temple now offers an admissions option A program of the Kornberg School of Italy, fights the disease in his lab and in that doesn’t require standardized-test results. Dentistry links low-income children in North his hometown. Philadelphia with preventive dental care. 10 Innovation Dedication: In the new Science Education and Research Center, scientists and students pioneer groundbreaking research. ON THE COVER: Illustration by Eleanor Grosch WINTER 2015 LETTERS During WWII, I was assigned to the 142nd General Hospital in Kolkata, India, from 1945 to 1946. -

October 1-31, 2015

Movie Show Times: October 1-31, 2015 Phone: (954) 262-2602, Email: [email protected] , www.nova.edu/sharksunitedtv 2015 1:30 AM 3:30 AM 6:00 AM 8:00 AM 10:30 AM 12:30 PM 3:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 9:30 PM 11:30 PM One Flew Over the Pitch Perfect 2 Shutter Island Extinction Furious 7 The Age of Adeline Ghostbusters Moneyball American Psycho Barely Lethal Friday the 13th Oct. 1 Cuckoo's Next Oct. 2 Beetle Juice 42 Hotel Transylvania Girl Interrupted Amityville Horror Love & Mercy Hot Pursuit The Soloist Animals Pitch Perfect 2 Extinction Oct. 3 The Age of Adeline Furious 7 Ghostbusters Shutter Island American Psycho Moneyball Barely Lethal 42 Friday the 13th Beetle Juice Hotel Transylvania One Flew Over the Amityville Horror Girl Interrupted Hot Pursuit Love & Mercy Animals The Soloist Pitch Perfect 2 Extinction The Age of Adeline Ghostbusters Oct. 4 Cuckoo's Next Oct. 5 American Psycho Moneyball Barely Lethal 42 Friday the 13th Girl Interrupted Beetle Juice Love & Mercy Hotel Transylvania Amityville Horror Hot Pursuit Oct. 6 Animals The Soloist Pitch Perfect 2 Moneyball Extinction Shutter Island The Age of Adeline Furious 7 Ghostbusters American Psycho Barely Lethal One Flew Over the Friday the 13th Beetle Juice Girl Interrupted Hotel Transylvania Love & Mercy Amityville Horror The Soloist Hot Pursuit Animals Pitch Perfect 2 Oct. 7 Cuckoo's Next One Flew Over the Extinction Shutter Island The Age of Adeline Furious 7 Ghostbusters American Psycho Moneyball Barely Lethal Friday the 13th Beetle Juice Oct. 8 Cuckoo's Next Oct. -

Fanboys-Production-Notes.Pdf

International Production Notes SYNOPSIS Set in 1998, the film, starring Jay Baruchel (KNOCKED UP, MILLION DOLLAR BABY), Tony Award Winner Dan Fogler (KUNG FU PANDA, “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee”), Sam Huntington (SUPERMAN RETURNS, NOT ANOTHER TEEN MOVIE), Chris Marquette (THE GIRL NEXT DOOR, ANOTHER WORLD), and Kristen Bell (FORGETTING SARAH MARSHALL, PULSE) is a heart-warming comedy that follows a group of young, passionate STAR WARS fans on a cross-country quest to break into George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch and watch STAR WARS: EPISODE 1- THE PHANTOM MENACE, before it’s released. FANBOYS is a production of Trigger Street Productions and Picture Machine. The film is directed by Kyle Newman and produced by Kevin Spacey, Dana Brunetti, Evan Astrowsky and Matthew Perniciaro. The screenplay is written by Adam F. Goldberg and Ernest Cline from a story by Ernest Cline and Dan Pulick. Kevin Mann served as executive producer. 2 CAST Eric SAM HUNTINGTON Linus CHRISTOPHER MARQUETTE Hutch DAN FOGLER Windows JAY BARUCHEL Zoe KRISTEN BELL FILMMAKERS Directed by KYLE NEWMAN Screenplay ERNEST CLINE and ADAM F. GOLDBERG Story by ERNEST CLINE and DAN PULICK Produced by DANA BRUNETTI KEVIN SPACEY MATTHEW PERNICIARO EVAN ASTROWSKY Executive Producer KEVIN MANN 3 FANBOYS About the Cast SAM HUNTINGTON / Eric Sam Huntington has appeared on screen, television and stage. His film credits include, SUPERMAN RETURNS, NOT ANOTHER TEEN MOVIE, DETROIT ROCK CITY and can be seen in the upcoming TUG. On television, he has appeared in featured roles on LAW & ORDER, CSI: Miami, CSI: NY, and VERONICA MARS. Huntington appears on stage with The Peterborough Players in “The Nerd,” “Waiting for Godot” and “To Kill A Mockingbird.” While with the Black Box Theatre Company he appeared in “The New Kid,” “Gifts,” “The Guest Speaker” and “Not The King.” CHRIS MARQUETTE / Linus Possessing the rare ability to thoroughly embody each character he portrays, Chris Marquette’s intensity on screen, good looks and charm warrants him as one of the most gifted actors of his generation. -

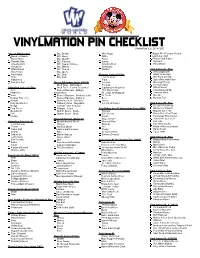

VM Pin Checklist Copy

VINYLMATION PIN CHECKLIST Checklist 1.1 (1/4/15) Alice In Wonderland DCL Dream Miss Piggy Buzz's XP-37 Space Cruiser Queen of Hearts DCL Magic Rizzo Lightning's Bolt Oyster Baby DCL Wonder Rowlf Flowers and Fairies Tweedle Dee DCL Fantasy Statler Figment Tweedle Dum DCL Captain Mickey Swedish Chef Dreamfinder Caterpillar DCL Minnie Sweetums White Rabbit DCL Donald Waldorf Park Series #6 - Pins March Hare DCL Goofy DHS Clapboard Mad Hatter DCL Chip Muppets Series #2 Pins WDW Road Sign Dodo DCL Dale Lew Zealand Wet Paint Donald Hedgehog Pepe Space Mountain Paris Cheshire Cat Disney Afternoon Series 2(2013) Scooter Monorail Orange Duck Tales - Gizmoduck Penguin Sonny Eclipse Animation Series #1 Pins Duck Tales - Fenton Crackshell Captain Link Hogthrob DCL Lifeboat Alice Rescue Rangers - Gadget First Mate Piggy Adventureland Tiki Peter Pan Hackwrench Dr. Julius Strangepork Primeval Whirl Marie Rescue Rangers - Monterey Jack Dr. Teeth Monstro Donkey Pinocchio Rescue Rangers - Zipper Jr. Zoot Norway Troll Aladdin Darkwing Duck - Bushroot Janice Fairy Godmother Darkwing Duck - Negaduck Sgt. Floyd Pepper Park Series #7 - Pins Dodge Talespin - Don Karnage Donald Philharmagic Frog Prince Talespin - Louie Park/Urban Ser. #1 Vinylmation Pins (2008) America on Parade Quasimodo Gummi Bears - Cubbi Figment Muppet Vision 3D Phil Gummi Bears - Gruffi ELP Mickey Tinker Bell’s First Flight Mushu Kermit Polynesian Fire Dancer Haunted Manson Series #1 Magical Stars Figment in Spacesuit Animation Series 2 - 3” Great Ceasar’s Ghost Monorail Red Star Jets Jose Carioca Phineas Teacups Kali River Rapids Flower Hat Box Ghost Yeti World of Motion Serpent Tinker Bell Captain Bartholomew Oopsy Earful Tower Dopey King El Super Raton Epcot 2000 Sebastian Master Gracey Balloon (Chaser) John Henry Singing Bust Park Series #8 - Pins Kim Possible Gus Park Series #2 Vinylmation Pins (2009) Blizzard Beach Snowman Baloo Constance Hatchaway Aquaramouse Buddy Tigger Captain Cullpepper Festival of the Lion King Minnie Moo Fantasia Donald The Executioner Crossroads of the World MK 10th Anniv. -

Happy Holidays from C 4 Mobile Detailing!

MELBOURNE WEST MELBOURNE GO ELECTRIC @HometownNewsBrevard @hometownnewsbrevard @HometownNewsBre GO Electric Services, LLC Vol. 14, No. 19 www.HometownNewsBrevard.com Friday, November 24, 2017 “We provide you OFF TO OREGON TWO BIG CATCHES PRECIOUS PIPER the power!” www.goelectricservices.com Lois and Bill Stearly, Dominic Thompson, Piper the Maltese granddaughter Peyton, Evin Breemen land loves to jump on her Mark P. Giarrizzo stop at a restaurant a tarpon and snook siblings, cuddle Lic# 13007758 •Insured [email protected] TOURING WITH THE TOWNIES 12 CATCH OF THE WEEK 13 PET OF THE WEEK 14 Cell: 561-315-8448 15% Military 24-Hour Emergency Service Discount Digital Cruisin' classic style Marketing Space Solutions From a company Coast you trust! getting new jobs For Hometown News [email protected] MELBOURNE – Melbourne has joined the line-up of locations for Services: Enhanced Resource Centers (ERC), one of the fastest-growing contact Google Ads centers in the United States. The new Social Media Ads location on John Rodes Boulevard is anticipating bringing 400 news jobs Facebook Page Alex Schierholtz/staff photographer to the Space Coast, with full employ- Management Mike Hedrick of Palm Bay discusses his 1929 Erskine Studebaker with Barry ment expected by March 2018. Website Design “We are pleased ERC chose Mel- Bartolino of West Melbourne during the Malabar Fall Fest Car Show on Nov. bourne,” said Lynda Weatherman, Good Rankings (SEO) 18 at Malabar Community Park. president and CEO of the Economic And More! Development Commission of Flori- da’s Space Coast (EDC). “Their investment in our community is Call 321-242-1013 for Merrill Lynch helps rescue extraordinary, as the 400 new posi- a FREE consultation tions offer job seekers a unique opportunity with growth potential for your unique Melbourne Light Parade within the BPO industry.” business needs. -

THE COMIC THAT SAVED MARVEL” TURNS $9.95 in the USA

Roy Thomas’Star-Crossed LORDIE, LORDIE! Comics Fanzine “THE COMIC THAT SAVED MARVEL” TURNS $9.95 In the USA 40!40! No.145 March 2017 WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR BE CAREFUL YOU DON’T WIND UP WITH WARS NOW! 100 PAGES IN FULL COLOR! 1 82658 00092 9 "MAKIN' WOOKIEE" with CHAYKIN & THOMAS Vol. 3, No. 145 / March 2017 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Contents Proofreaders Writer/Editorial: Star Wars—The Comic Book—Turns 40! . 2 Rob Smentek Makin’ Wookiee. 3 William J. Dowlding Roy Thomas tells Richard Arndt about the origins and pitfalls of Marvel’s 1977 Star Wars Cover Artist comic. Howard Chaykin Howard Chaykin On Star Wars . 54 Cover Colorist The artist/co-adapter of Star Wars #1-10 takes a brief look backward. Unknown Rick Hoberg On Star Wars . 58 With Special Thanks to: From helping pencil Star Wars #6—to a career at Lucasfilm. Rob Allen Jim Kealy Heidi Amash Paul King Bill Wray On Star Wars. 63 Pedro Angosto Todd Klein Rick Hoberg dragged him into inking Star Wars #6—and Bill’s glad he did! Richard J. Arndt Michael Kogge Rodrigo Baeza Paul Kupperberg The 1978 Star Wars Comic Adaptation . 67 Bob Bailey Vicki Crites Lane Lee Harsfeld takes us on a tour of veteran comics artist Charles Nicholas’ version of Mike W. -

Science Fictional the Aesthetics of Science Fiction Beyond the Limits of Genre

Science Fictional The Aesthetics of Science Fiction Beyond the Limits of Genre Andrew Frost University of NSW | College of Fine Arts PhD Media Arts 2013 4 PLEASE TYPE Tl<E UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Tht:tltiDittorUdon Sht•t Surname or Fenily name: Frost FIRI neme; Andrew OCher namels: Abbr&Yia~lon fof" dcgrco as given in the Unlverslty caltn<S:ar. PhD tCOde: 1289) Sd'IOOI; Seh.ool Of Media Arts Faculty; Coll999 of A ne Am Title: Science Fletfonar.: The AestheUes or SF Beyond the Limit:t of Gcnt'O. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) ScMtnce Flcdonal: The Anthetics of SF Beyond the Umlts of Genre proposes that oonte~my eufture 1$ * $pallal e)Cl>ertence dom1nS'ed by an aesane(IC or science liction and its qua,;.genefic form, the ·$dence ficdonal', The study explores the connective lines between cultural objects suet! as film, video art. painting, illustration, advertising, music, and children's television in a variety ofmediums and media coupled with research that conflates aspects of ctitical theory, art history a nd cuttural studies into a unique d iscourse. The study argues thai three types of C\lltural e ffeets reverberation. densi'ly and resonanoe- affect cultural space altering ood changing the 1ntel'l)totation and influeooe of a cuUural object Through an account of the nature of the science fictional, this thesis argues that science fiction as wo uncJersland It, a.nd how 11 has beon oooventionally concefved, is in fact the counter of its apparent function within wider culture. While terms such as ·genre~ and ·maln-stream• suggest a binary of oentre and periphery, this lh-&&is demonstrates that the quasi-generic is in fact the dominant partner in the process of cultural production, Ocelamlon ,.~ lo disposition or projoct thnlsJdtuen.tlon I htrOby grltlt t<> I~ Ul'll\IOI'IiiY Of Now SOUIJ'I WaltS or i&& agents the rlg:tlllo ard'llve anct to INike available my ttwrsl9 or di$sertabon '" whole or in 1»Jt il'lllle \Jtlivetsay lbrsrles., at IOtmS Of tnedb, rtOW or hero <~~Ot kncwn, 5tAijod:.lo lho Jl«Mdonll ol lho Co9yrlghlt Act 1968. -

Movielistings

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 25, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESDAY’S SATURDAY EVENING MAY 26, 2007 SUNDAY EVENING MAY 27, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Family Jewels Family Jewels Gene Simmons Family The First 48 Burned Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Flip This House Profit chal- Flip This House (TV G) Jackpot Diaries, Part 2 Profile of lottery winners from Flip This House Profit chal- 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E lenge. (TV G) (R) (R) Texas and California. (TVPG) (N) lenge. (TV G) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) Jewels (TV14) (R) corpse. -

An International Journal of English Studies 26/1 2017

ANGLICA An International Journal of English Studies 26/1 2017 EDITOR Grażyna Bystydzieńska [[email protected]] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Marzena Sokołowska-Paryż [[email protected]] Anna Wojtyś [[email protected]] ASSISTANT EDITORS Katarzyna Kociołek [[email protected]] Magdalena Kizeweter [[email protected]] Przemysław Uściński [[email protected]] ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDITOR Barry Keane [[email protected]] ADVISORY BOARD GUEST REVIEWERS Michael Bilynsky, University of Lviv Dorota Babilas, University of Warsaw Andrzej Bogusławski, University of Warsaw Bartłomiej Błaszkiewicz, University of Warsaw Mirosława Buchholz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Maria Błaszkiewicz, University of Warsaw Bernhard Diensberg, University of Bonn Rafał Borysławski, University of Silesia, Katowice Edwin Duncan, Towson University Anna Branach-Kallas, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Jacek Fabiszak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Janusz Kaźmierczak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Jacek Fisiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Anna Krawczyk-Łaskarzewska, University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn Ewa Łuczak, University of Warsaw Elzbieta Foeller-Pituch, Northwestern University, Evanston-Chicago Małgorzata Łuczyńska-Hołdys, University of Warsaw Piotr Gąsiorowski, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań David Malcolm, University of Gdańsk Keith Hanley, Lancaster University Marek Paryż, University of Warsaw Andrea Herrera, University of Colorado Daniel Reynaud, Avondale College of Higher Education, Australia Christopher Knight, University of Montana Karolina Rosiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Marcin Krygier, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Paweł Stachura, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Krystyna Kujawińska-Courtney, University of Łódź Ryszard Wolny, University of Opole Zbigniew Mazur, Marie Curie-Sklodowska University, Lublin Rafał Molencki, University of Silesia, So snowiec John G. Newman, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Michal Jan Rozbicki, St.