Jerry Izenberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Once a Day”--Connie Smith (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2020 Essay by Barry Mazor (Guest Post)*

“Once a Day”--Connie Smith (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2020 Essay by Barry Mazor (guest post)* Bill Anderson, Connie Smith and Bob Ferguson in the studio Just months before Connie Smith would step up to the microphone at RCA Records’ Music Row Studio B for her very first recording session, she was a virtually unknown Ohio housewife who’d performed at nearby fairs and on local television. Then, fatefully, at an August 1963 talent contest near Columbus, the contest judge proved to be recording star and country songwriting master Bill Anderson. He would note in his memoir, “None of us could believe such a big voice was coming out of such a petite lady.” He’d told her that if she ever came to Nashville to pursue a country career, he’d be there for her. It took her months to decide to give that a try. RCA’s Nashville label head, Chet Atkins, was impressed by her demo tapes, and when Anderson assured him that he’d have new songs for her that could help get her established, she was signed to the label and in the studio within three weeks. Constance June Meador Smith was 23 as her recording career began that day--July 16, 1964--a young wife and mother. The third song she recorded at that first session, Bill Anderson’s “Once a Day,” in which the singer tells us how the loss of a love to another can be devastating, and as a matter of fact, there’s no denying it has been, would become a country music phenomenon. -

Christmas Comes but Once a Day

Christmas Comes But Once A Day Jim Reed CHRISTMAS COMES BUT ONCE A DAY CHRISTMAS COMES BUT ONCE A DAY Jim Reed BLUE ROOSTER PRESS Birmingham, Alabama USA www.blueroosterpress.com BOOKS BY JIM REED Christmas Comes But Once A Day Dad’s Tweed Coat: Small Wisdoms Hidden Comforts Unexpected Joys How to Become Your Own Book: The Joy of Writing for You and You Alone (The Importance of Space Ships, Time Capsules and Messages in Bottles) Not Another Poetry Book (Another Poetry Book) Inward Tales: Dancing Around Race, Racism and Racists Small-Town Red Clay Tales, Both Actual and True Not Enough Sleep: Insomniac Tales BOOKS BY JIM REED AND OTHERS I Wish I Was In Dixie edited by Marie Stokes Jemison and Jim Reed Superrelations by Gina Boyd and Jim Reed Horace the Horribly Hoarse Horse by Jim Reed and T.R. Reed OTHER WRITINGS BY JIM REED Christmas Comes But Once A Day story by Jim Reed in An Alabama Christmas: 20 Heartwarming Tales by Truman Capote, Helen Keller, and More One of Those Thanksgiving Days in Verbena, Alabama poem by Jim Reed in Whatever Remembers Us: An Anthology of Alabama Poetry edited by Sue Brannan Walker & J. William Chambers Private Lessons story by Jim Reed in Alabama Scrapbook by Ellen Sullivan and Marie Stokes Jemison Beards Beards Beards by Helen Bunkin with foreword by Jim Reed Grove of the Dolls story by Jim Reed in The Alalitcom/2001 edited by Donna Jean Tennis and John Curbow A Box of Trinkets by Allen Johnson Jr. with foreword by Jim Reed CHAP BOOKS BY JIM REED: Sticky Novels: Tales Jotted Down on Sticky Notes by Jim Reed Stickier Novels: Yet More Tales Jotted Down on Sticky Notes by Jim Reed Marilyn of the Uncreased Elbow by Jim Reed Glugged Not Stirred by Jim Reed CHRISTMAS COMES BUT ONCE A DAY Jim Reed CHRISTMAS COMES BUT ONCE A DAY. -

$>Tate of \!Tennessee

$>tate of \!tennessee SENATE JOINT RESOLUTION NO. 561 By Senators Johnson, Kyle, Beavers, Bell, Bowling, Burks, Campfield, Crowe, Dickerson, Finney, Ford, Gardenhire, Green, Gresham, Haile, Harper, Henry, Hensley, Kelsey, Ketron, Massey, McNally, Niceley, Norris, Overbey, Southerland, Stevens, Summerville, Tate, Tracy, Watson, Yager, Mr. Speaker Ramsey and Representatives Matthew Hill, Ryan Williams A RESOLUTION to recognize Connie Smith on the fiftieth anniversary of her illustrious country music career and her forty-ninth anniversary as a member of the Grand Ole Opry. WHEREAS, it is fitting that this General Assembly should recognize those gifted artists who have experienced great success in the world of country music; and WHEREAS, Constance June Meador, better known to her legions of fans as Connie Smith, was born August 14, 1941 , to parents Hobart and Wilma Meador in Elkhart, Indiana; she grew up in Ohio where she fell in love with country music listening to the Louvin brothers, George Jones, and Loretta Lynn on Grand Ole Opry broadcasts from Nashville, Tennessee; and WHEREAS, her love of singing was discovered in 1963 by singer-songwriter Bill Anderson. Connie was a housewife and mother with a four-month-old son in Warner, Ohio, when she and her husband went to see a country music show at Frontier Ranch near Columbus, Ohio. She was talked into entering a talent contest, which she won, enabling her to meet Bill, who invited her to sing on the Ernest Tubb Midnight Jamboree in March 1964. A few months later Bill invited her back to Nashville to record some demo records; and WHEREAS, in June 1964 Connie was signed to a contract with RCA Victor Records by Chet Atkins, who called her "the greatest girl singer he'd ever heard." She soon cut her very first recording entitled, "Once a Day," which would be a phenomenon in country music history. -

GC01 Pcversion.Pdf

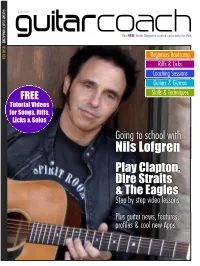

GUITAR COACH MAGAZINE : GUITAR Issue 001 The FREE Guitar Magazine created exclusively for iPad ISSUE 001 Beginners Bootcamp Riffs & Licks Coaching Sessions Guitars & Gizmos FREE Skills & Techniques Tutorial Videos for Songs, Riffs, Licks & Solos Going to school with Nils Lofgren Play Clapton, Dire Straits & The Eagles Step by step video lessons Plus guitar news, features, profiles & cool new Apps. MAGAZINE Editorial enquiries: [email protected] Advertising enquiries: [email protected] www.guitarcoachmag.com PRESS and HOLD the screen here to show the top bar navigation. TAP HOME to return to Guitar Coach Magazine home page. How to use this App... SWIPE horizontally to go to the next page PRESS and HOLD the screen here to show the bottom navigation bar. SWIPE horizontally to quickly navigate pages. TAP selected page to view. Issue 001 Contents Features Note from the Editor 5 Nils Lofgren...page 33 Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band’s legendary News in brief 6 guitarist Nils Lofgren shares some Guitar Guitarist profile 14 School secrets and much more... Ask Andy 19 Chord of the month 20 Guitar Top 10s 29 Song writing tips 41 FAQs 43 From Tabs to Apps...page 26 Lesson Videos, Tutorials and Tips Songsterr brings together technology and tabs in one super cool App - it’s a must-have Beginners Bootcamp 7 tool... From buying your first guitar, to playing songs and staying motivated. Coaching Session 16 A short 20 minute session to get you working on your power chords and playing Clapton Skills & Techniques 23 Steve Stine...page 21 Time for some string bending and a great lick from Dire Straits and Guitar George As a top guitarist and teacher, both online and offline, Steve Stine offers his tips for learning quickly and easily.. -

Message for Sunday, April 30, 2006

1 Message for Sunday, April 25, 2021 The Rev. Michael Burke Preached at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church Anchorage, Alaska Little Children, Let Us Love One Another… Yesterday, I was working at home, and had the window open to let in the Spring air. From outside in the street came the sounds of neighborhood kids, laughing and riding their bikes and longboards in front of my house. For a moment there I was swept up in memories of my own childhood, riding my emerald green bike with the sunshine gold banana seat through the puddles formed in the street by melting snow. It was a melancholy, nostalgic feeling for a time that never really was, except in hindsight: but when all seemed right with the world to a seven-year-old kid. There were three major TV networks and the news only came on once a day for a twenty-two-minute broadcast. And when the news anchor Walter Cronkite signed off at 6:30pm and said, “and that’s the way it is”, it seemed that everybody trusted that it was so. My iPhone on the desk dinged with a pop-up alert, bringing me back to 2021. News and fallout from the Chauvin trial continues, one small moment of justice amidst a sea of more troubling developments. But nobody wins. A man is going to prison for a very long time. A man, George Floyd is dead. His family will never again hold him, see him smile, hear his laughter fill the air and mingle with theirs. A conviction does not bring him back. -

THE SONG of the BIRD Anthony De Mello S

THE SONG OF THE BIRD Anthony de Mello S. J. This book has been written for people of every persuasion religious and non religious, I cannot, however, hide from my readers the fact that I am a priest of the Catholic Church. I have wandered free-ly in mystical traditions that are not Christian and not religious and I have been profoundly influenced by them. It is to my Church, however, that I keep returning, for she is my spiritual home; and while I am acutely, sometimes embarrassingly, conscious of her limitations and narrowness, I also know that it is she who has formed me and made me what I am today. So it is to her that I gratefully dedicate this book. Everyone loves stories and you will find plenty of them in this book: Stories that are Buddhist, Christian, Zen, Hasidic, Russian, Chinese, Hindu, Sufi; stories ancient and contemporary. And they all have a special quality: if read in a cer-tain kind of way, they will produce spiritual growth. HOW TO READ THEM There are three ways: 1. Read a story once. Then move on to another. This manner of reading will give you entertainment. 2. Read a story twice. Reflect on it. Apply it to your life. That will give you a taste of theology. This sort of thing can be fruitfully done in a group where the members share their reflections on the story. You then have a theological circle. 3. Read the story again, after you have reflected on it. Create a silence within you and let the story reveal to you its inner depth and meaning: something beyond words and reflections. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Aprilverch.Com Fiddler, Singer, and Stepdancer April Verch Knows How

Fiddler, singer, and stepdancer April Verch knows how relevant an old tune can be. She was raised surrounded by living, breathing roots music—her father’s country band rehearsing; the lively music at church and at community dances; the tunes she rocked out to win fiddle competitions. She thought every little girl learned to stepdance at the age of three and fiddle at the age of six. She knew nothing else and decided early on that she wanted to be a professional musician. She took that leap, and for over two decades has been recording and captivating audiences worldwide, exploring new and nuanced places each step of the way. On April 12, 2019, Verch released her twelfth recording, Once A Day, via Slab Town Records. A followup to her 2017 career-spanning release The April Verch Anthology, this new album is a heartfelt homage to 1950s and 60s classic country. Recorded in Nashville by Bil VornDick and produced by Doug Cox, Once A Day features the talents of country veterans including steel guitarist Al Perkins (Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris), guitarist Redd Volkaert (Merle Haggard) and fiddler Kenny Sears (Mel Tillis, Grand Ole Opry). From the title track, a hit debut single for Connie Smith, to Loretta Lynn’s “You Ain’t Woman Enough,” and Webb Pierce’s “You’re Not Mine Anymore,” the album is a dynamic crash course in one of Country Music’s most influential time periods. Her admiration for these musicians and this iconic era is evident from start to finish. Void of contemporary gimmicks and over-‐production, Verch revels in the history and lets the music speak for itself. -

Ebook Download Guitar Chords & Scales: an Easy Reference for Acoustic Or Electric Guitar

GUITAR CHORDS & SCALES: AN EASY REFERENCE FOR ACOUSTIC OR ELECTRIC GUITAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hal Leonard Corp | 56 pages | 01 Feb 2003 | Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation | 9780634052736 | English | none Guitar Chords & Scales: An Easy Reference for Acoustic or Electric Guitar PDF Book I've got you covered. Free printable guitar chord chart. Related Searches. View Product. Guitar Chords Deluxe Guitar Educational. Recommended Scales. Fast loading desktop and mobile experience Auto-resume across devices Quick search, note taking and bookmarking for easy reference Responsive book design, so things look great on mobile too New books being added regularly This convenient reference features a clear, concise, simple and visual approach to keyboard and guitar chords. Play on. As you'll quickly learn the more connected you come with your guitar, tuning is vitally important to your success in playing. Whatever guitar you pick, make sure it inspires you. After that turn on your metronome and move between the chords. It syncs automatically with your account and allows you to read online or offline wherever you are. Account Options Sign in. Use a metronome at first when you are able to change between them without it. Thank you. This is true, if your child is between the ages of , a smaller guitar can work. Advertising seems to be blocked by your browser. So I bought the same book and went though the chord shapes once a day for a couple of months. Start making music. Acoustic guitars are often considered harder to learn. They are quick and easy to use. Arpeggio Information. Chords for Keyboard and Guitar - A Pocket. -

“The Stories Behind the Songs”

“The Stories Behind The Songs” John Henderson The Stories Behind The Songs A compilation of “inside stories” behind classic country hits and the artists associated with them John Debbie & John By John Henderson (Arrangement by Debbie Henderson) A fascinating and entertaining look at the life and recording efforts of some of country music’s most talented singers and songwriters 1 Author’s Note My background in country music started before I even reached grade school. I was four years old when my uncle, Jack Henderson, the program director of 50,000 watt KCUL-AM in Fort Worth/Dallas, came to visit my family in 1959. He brought me around one hundred and fifty 45 RPM records from his station (duplicate copies that they no longer needed) and a small record player that played only 45s (not albums). I played those records day and night, completely wore them out. From that point, I wanted to be a disc jockey. But instead of going for the usual “comedic” approach most DJs took, I tried to be more informative by dropping in tidbits of a song’s background, something that always fascinated me. Originally with my “Classic Country Music Stories” site on Facebook (which is still going strong), and now with this book, I can tell the whole story, something that time restraints on radio wouldn’t allow. I began deejaying as a career at the age of sixteen in 1971, most notably at Nashville’s WENO-AM and WKDA- AM, Lakeland, Florida’s WPCV-FM (past winner of the “Radio Station of the Year” award from the Country Music Association), and Springfield, Missouri’s KTTS AM & FM and KWTO-AM, but with syndication and automation which overwhelmed radio some twenty-five years ago, my final DJ position ended in 1992. -

Connie Smith the Cry of the Heart

Connie Smith The Cry of the Heart “If you’re talking about a country singer, there ain’t nobody better.” – Merle Haggard on Connie Smith “There’s really only three real female singers: Streisand, Ronstadt, and Connie Smith. The rest of us are only pretending.” – Dolly Parton Dolly Parton and the late George Jones and Merle Haggard have all sung her praises. The deeply emotive vocal style of Connie Smith has never wavered since her national debut in 1964 with the smash C&W hit, “Once a Day” – a chart-topper for eight weeks. The RCA single, recently selected by the Library of Congress for its National Song Registry, set the template for Smith’s aching contralto that still sends chills down the spine, all these decades later. But Smith takes her time and makes her public wait: First, after a decade of stardom, she stepped back to raise her five children, before returning to the studio in the late ‘90s with master musician, recording artist, and producer Marty Stuart. They not only made a great album, they fell in love and married; another well-received Stuart-produced Smith LP followed in 2011. Now, the powerful new Cry of the Heart marks the couple’s third classic-country collaboration, and Smith’s first album in a decade. “Here’s what I learned about loving and living and working with Connie,” Stuart explains. “She makes a record when she’s ready and nothing pushes her in that direction until she’s in the mood and space to do it and the songs are right.