I Once Saw Darrell Scott Sit Down and Play a Song at Somebody’S Show at the Bluebird Café, and It Put Me Right on My Ass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

14Th Annual ACM Honors Celebrates Industry & Studio Recording Winners from 55Th & 56Th ACM Awards

August 27, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, August 27, 2021 14th Annual ACM Honors Celebrates SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) Industry & Studio Recording Winners From 55th & 56th ACM Awards If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES 14th Annual ACM Honors Beloved TV Journalist And Producer Lisa Lee Dies At 52 “The Storyteller“ Tom T. Hall Passes Luke Combs accepts the Gene Weed Milestone Award while Ashley McBryde Rock And Country Titan Don looks on. Photo: Getty Images / Courtesy of the Academy of Country Music Everly Passes Kelly Rich To Exit Amazon The Academy of Country Music presented the 14th Annual ACM Honors, Music recognizing the special award honorees, and Industry and Studio Recording Award winners from the 55th and 56th Academy of Country SMACKSongs Promotes Music Awards. Four The event featured a star-studded lineup of live performances and award presentations celebrating Special Awards recipients Joe Galante and Kacey Musgraves Announces Rascal Flatts (ACM Cliffie Stone Icon Award), Lady A and Ross Fourth Studio Album Copperman (ACM Gary Haber Lifting Lives Award), Luke Combs and Michael Strickland (ACM Gene Weed Milestone Award), Dan + Shay Reservoir Inks Deal With (ACM Jim Reeves International Award), RAC Clark (ACM Mae Boren Alabama Axton Service Award), Toby Keith (ACM Merle Haggard Spirit Award), Loretta Lynn, Gretchen Peters and Curly Putman (ACM Poet’s Award) Old Dominion, Lady A and Ken Burns’ Country Music (ACM Tex Ritter Film Award). Announce New Albums Also honored were winners of the 55th ACM Industry Awards, 55th & 56th Alex Kline Signs With Dann ACM Studio Recording Awards, along with 55th and 56th ACM Songwriter Huff, Sheltered Music of the Year winner, Hillary Lindsey. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

Shinedownthe Biggest Band You've Never Heard of Rocks the Coliseum

JJ GREY & MOFRO DAFOE IS VAN GOGH LOCAL THEATER things to do 264 in the area AT THE PAVILION BRILLIANT IN FILM PRODUCTIONS CALENDARS START ON PAGE 12 Feb. 28-Mar. 6, 2019 FREE WHAT THERE IS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND THE BIGGEST BAND YOU’VE NEVER SHINEDOWN HEARD OF ROCKS THE COLISEUM ALSO INSIDE: ADAM BAKER & THE HEARTACHE · CASTING CROWNS · FINDING NEVERLAND · JO KOY whatzup.com Just Announced MAY 14 JULY 12 JARED JAMES NICHOLS STATIC-X AND DEVILDRIVER GET Award-winning blues artist known for Wisconsin Death Trip 20th Anniversary energetic live shows and bombastic, Tour and Memorial Tribute to Wayne Static arena-sized rock 'n' roll NOTICED! Bands and venues: Send us your events to get free listings in our calendar! MARCH 2 MARCH 17 whatzup.com/submissions LOS LOBOS W/ JAMES AND THE DRIFTERS WHITEY MORGAN Three decades, thousands of A modern day outlaw channeling greats performances, two Grammys, and the Waylon and Merle but with attitude and global success of “La Bamba” grit all his own MARCH 23 APRIL 25 MEGA 80’S WITH CASUAL FRIDAY BONEY JAMES All your favorite hits from the 80’s and Grammy Award winning saxophonist 90’s, prizes for best dressed named one of the top Contemporary Jazz musicians by Billboard Buckethead MAY 1 Classic Deep Purple with Glenn Hughes MAY 2 Who’s Bad - Michael Jackson Tribute MAY 4 ZoSo - Led Zeppelin Tribute MAY 11 Tesla JUNE 3 Hozier: Wasteland, Baby! Tour JUNE 11 2 WHATZUP FEBRUARY 28-MARCH 6, 2019 Volume 23, Number 31 Inside This Week LIMITED-TIME OFFER Winter Therapy Detailing Package 5 Protect your vehicle against winter Spring Forward grime, and keep it looking great! 4Shinedown Festival FULL INTERIOR AND CERAMIC TOP COAT EXTERIOR DETAILING PAINT PROTECTION Keep your car looking and Offers approximately four feeling like new. -

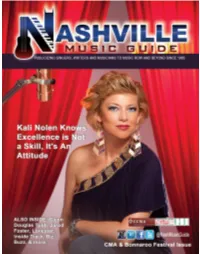

Nashvillemusicguide.Com 1

NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 NMG-13BBKingsAd_NMG-13BBKingsAd 5/20/13 3:01 PM Page 1 FFRREEEE TToo TThhee PPuubblliicc BBBB KKiinnggss TThhuurrssddaayy,, JJuunnee 66,, FFrroomm 1111AAMM ttoo 44::3300PPMM TTiirreedd OOff WWaallkkiinngg && WWaaiittiinngg?? GGeett OOffff YYoouurr FFeeeett,,, EEnnjjooyy AAiirr CCoonnddiittiioonniinngg AAnndd LLiivvee CCoouunnttrryy MMuussiicc!! AAtt TThhee FFaammoouuss BBBB KKiinngg’’’ss LLoowweerr LLeevveell CClluubb AAtt 115522 SSeeccoonndd AAvveennuuee John Berry Stella Parton Razzy Bailey J.D. Shelburne JohnBerry.com StellaParton.com myspace.com/razzybailey JDShelburne.com “NAKED COWGIRL” Angela Hesse Lydia Hollis Ethan Harris Kristina Craig Band Daniel Alan AngelaHesse.com LydiaHollis.com EthanHarrisMusic.com KristinaCraig.com DanielAlan.net $andy Kane Rachel Dampier Fort Mountain Boys Sheylyn Jaymes Brit Jones Tera Townsend RachelDampier.com SheylynJaymes.com BritJones.com TeraTownsend.com Hit Single “I Love Nick” from NBC’s America’s Got Talent with Nick Cannon Alison Birdsong Ginger Harvey Reese Lane Alisa Star Tony Watson For Bookings & All Other Info Call AlisonBirdsong.com GingerHarvey.com ReeseLane.com AlisaStarMusic.com TonyWatsonUS.com 212.561.1838 AArrrriiivvee EEaarrlllyy TToo RReecceeiiivvee AA FFrreeee CCooppyy OOfff PPoowweerr SSoouurrccee MMaaggaazziiinnee && AA FFrreeee CCoommppiiilllaatttiiioonn DDiiisscc,,, NNoottt SSoollldd IIInn SStttoorreess (((WWhhiiilllee S Suuppppllliiieess L LLaassttt))) -or- [email protected] GGNashvilleMusicGuide.comeett AAuuttooggrraapphhss && PPiicctt2uurreess -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Country Airplay; Brooks and Shelton ‘Dive’ In

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JUNE 24, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Thomas Rhett’s Behind-The-Scenes Country Songwriters “Look” Cooks >page 4 Embracing Front-Of-Stage Artist Opportunities Midland’s “Lonely” Shoutout When Brett James sings “I Hold On” on the new Music City Puxico in 2017 and is working on an Elektra album as a member >page 9 Hit-Makers EP Songs & Symphony, there’s a ring of what-ifs of The Highwomen, featuring bandmates Maren Morris, about it. Brandi Carlile and Amanda Shires. Nominated for the Country Music Association’s song of Indeed, among the list of writers who have issued recent the year in 2014, “I Hold On” gets a new treatment in the projects are Liz Rose (“Cry Pretty”), Heather Morgan (“Love Tanya Tucker’s recording with lush orchestration atop its throbbing guitar- Someone”), and Jeff Hyde (“Some of It,” “We Were”), who Street Cred based arrangement. put out Norman >page 10 James sings it with Rockwell World an appropriate in 2018. gospel-/soul-tinged Others who tone. Had a few have enhanced Marty Party breaks happened their careers with In The Hall differently, one a lbu ms i nclude >page 10 could envision an f o r m e r L y r i c alternate world in Street artist Sarah JAMES HUMMON which James, rather HEMBY Buxton ( “ S u n Makin’ Tracks: than co-writer Daze”), who has Riley Green’s Dierks Bentley, was the singer who made “I Hold On” a hit. done some recording with fellow songwriters and musicians Sophomore Single James actually has recorded an entire album that’s expected under the band name Skyline Motel; Lori McKenna (“Humble >page 14 later this year, making him part of a wave of writers who are and Kind”), who counts a series of albums along with her stepping into the spotlight with their own multisong projects.