Goodie Mob and the Metaphysics of White Supremacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bradley Syllabus for South

Special Topics in African American Literature: OutKast and the Rise of the Hip Hop South Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D. Course Description In 1995, Atlanta, GA, duo OutKast attended the Source Hip Hop Awards, where they won the award for best new duo. Mostly attended by bicoastal rappers and hip hop enthusiasts, OutKast was booed off the stage. OutKast member Andre Benjamin, clearly frustrated, emphatically declared what is now known as the rallying cry for young black southerners: “the South got something to say.” For this course, we will use OutKast’s body of work as a case study questioning how we recognize race and identity in the American South after the civil rights movement. Using a variety of post–civil rights era texts including film, fiction, criticism, and music, students will interrogate OutKast’s music as the foundation of what the instructor theorizes as “the hip hop South,” the southern black social-cultural landscape in place over the last twenty-five years. Course Objectives 1. To develop and utilize a multidisciplinary critical framework to successfully engage with conversations revolving around contemporary identity politics and (southern) popular culture 2. To challenge students to engage with unfamiliar texts, cultural expressions, and language in order to learn how to be socially and culturally sensitive and aware of modes of expression outside of their own experiences. 3. To develop research and writing skills to create and/or improve one’s scholarly voice and others via the following assignments: • Critical listening journal • Nerdy hip hop review **Explicit Content Statement** (courtesy: Dr. Treva B. Lindsey) Over the course of the semester students will be introduced to texts that may be explicit in nature (i.e., cursing, sexual content). -

The Good Life Rich Nathan February 13 & 14, 2016 the Good Life John 10:1-10

The Good Life Rich Nathan February 13 & 14, 2016 The Good Life John 10:1-10 This week, our entire church, from preschoolers through adults, will begin to focus our attention for the next six weeks on The Good Life. What it is and how we can live it. All of my messages are followed up by a video teaching that all of our small groups will be watching in their small group meeting. We prayed to start up 350 new groups during this campaign. As of this weekend, 390 of you have signed up to host a group. I just want to say “thank you”! This is the very last weekend to sign up to host a group. Following the service, head out to the lobby at your campus to sign up to host a small group. Every attendee will receive a copy of the daily devotions that have been prepared for the six weeks of this Good Life series. We’ve already given out thousands of copies of the devotional. You don’t want to miss this, if you are not in small group, again head out to the lobby following the service to join a group or simply go online to vineyardcolumbus.org. Everyone will be talking about the Good Life. There’s a periodical out called The Vegan Good Life. Picture of the Magazine It’s advertised as being Packed with the very best in vegan fashion, travel, lifestyle, art and design So vegans have particular destinations for their travel. Would that include avoiding all roads that pass by dairy farms or ice cream stands? Making sure that the vehicle you’re traveling in has no leather seats? Vegan travel. -

Hip-Hop Artists Ali Big Gipp Drop 'Kinfolk' 8-15

Hip-Hop Artists Ali Big Gipp Drop 'Kinfolk' 8-15 Written by Robert ID2755 Wednesday, 21 June 2006 00:11 - Rap artist Ali, of the platinum selling hip-hop group St. Lunatics, and "Dirty South" hip-hop impresario Goodie Mob alum rap artist Big Gipp will be releasing their hip-hop collaborative debut album, Kinfolk, August 15th. Kinfolk comes following up their appearance on the #1 hit track ‘Grillz’ with fellow hip-hop artist Nelly and will be on his record label, Derrty Ent., an imprint of Universal Motown Records. The first single off the album, “Go ‘Head,” is an anthemic summer song that combines "midwest swing" with southern crunk and is produced by up and coming St. Louis native Trife. "Gipp and I started hanging out a while back and found that we had a lot in common," says Ali. "We''re both considered leaders in our crews, we''re fathers and even though we have different styles, we respect each other's skills." Gipp describes their collaborative effort as “the best of both worlds-- the St. Lunatics kicked off the midwest movement and Goodie Mob helped establish southern rap, that’s why I say it’s the best of both worlds; Plain and simple." In that spirit, Kinfolk has a mix of songs featuring "St. Louis" hip-hop kin: rap artists Nelly, Murphy Lee and Derrty Ent newcomers, Chocolate Tai and Avery Storm; "Atlanta" hip-hop kin Cee-lo and other southern hip-hop all-stars include rappers Juvenile, David Banner, Three 6 Mafia and Bun B. The album collab also contains a mix of mid-west and southern producers including the St. -

Outkast Stankonia Album Download Outkast Stankonia Album Download

outkast stankonia album download Outkast stankonia album download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67ab1adfff2e15e4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. MQS Albums Download. Mastering Quality Sound,Hi-Res Audio Download, 高解析音樂, 高音質の音楽. OutKast – Stankonia (20th Anniversary Deluxe) (2000/2020) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz] OutKast – Stankonia (20th Anniversary Deluxe) (2000/2020) FLAC (tracks) 24-bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 01:37:50 minutes | 1,11 GB | Genre: Hip- Hop, Rap Studio Master, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © LaFace – Legacy. OutKast is celebrating the 20th-anniversary of their seminal album Stankonia with a set of bonus tracks, previously unreleased remixes, streaming bundles and vinyl and digital editions. According to reports, the digital re-release will arrive in 24-bit and 360 Reality Audio formats, and will feature a total of six bonus tracks that include a remix of “B.O.B. (Bombs Over Baghdad)” by Zack de la Rocha of Rage Against The Machine, a remix of “Ms. Jackson” by Mr. Drunk, a remix of “So Fresh, So Clean” with Snoop Dogg and Sleepy Brown, plus a cappella versions of the three songs. -

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: a Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’S “Mainstream” (1996)

Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) MITCHELL OHRINER[1] University of Denver ABSTRACT: Recent years have seen the rise of musical corpus studies, primarily detailing harmonic tendencies of tonal music. This article extends this scholarship by addressing a new genre (rap music) and a new parameter of focus (rhythm). More specifically, I use corpus methods to investigate the relation between metric ambivalence in the instrumental parts of a rap track (i.e., the beat) and an emcee’s rap delivery (i.e., the flow). Unlike virtually every other rap track, the instrumental tracks of Outkast’s “Mainstream” (1996) simultaneously afford hearing both a four-beat and a three-beat metric cycle. Because three-beat durations between rhymes, phrase endings, and reiterated rhythmic patterns are rare in rap music, an abundance of them within a verse of “Mainstream” suggests that an emcee highlights the three-beat cycle, especially if that emcee is not prone to such durations more generally. Through the construction of three corpora, one representative of the genre as a whole, and two that are artist specific, I show how the emcee T-Mo Goodie’s expressive practice highlights the rare three-beat affordances of the track. Submitted 2015 July 15; accepted 2015 December 15. KEYWORDS: corpus studies, rap music, flow, T-Mo Goodie, Outkast THIS article uses methods of corpus studies to address questions of creative practice in rap music, specifically how the material of the rapping voice—what emcees, hip-hop heads, and scholars call “the flow”—relates to the material of the previously recorded instrumental tracks collectively known as the beat. -

Ceelo Green – Primary Wave Music

CEELO GREEN facebook.com/ceelogreen twitter.com/CeeLoGreen instagram.com/ceelogreen/ open.spotify.com/artist/5nLYd9ST4Cnwy6NHaCxbj8 Thomas DeCarlo Callaway (born May 30, 1974), known professionally as CeeLo Green (or Cee Lo Green), is an American singer, songwriter, rapper, record producer and actor. Green came to initial prominence as a member of the Southern hip hop group Goodie Mob and later as part of the soul duo Gnarls Barkley, with record producer Danger Mouse. Internationally, Green is best known for his soul work: his most popular was Gnarls Barkley’s 2006 worldwide hit “Crazy”, which reached number 1 in various singles charts worldwide, including the UK. In the United States, “Crazy” reached number two on the Billboard Hot 100. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Goodie Mob Amazing Grays Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Big Rube Amazing Break Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Calm B 4 Da Storm Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Survival Kit Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Back2Back Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Try We Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Off-Road Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Big Rube's Road Break Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob 4 My Ppl Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Dc Young Fly Crowe's Nest Break Survival Kit Organized Noize / Goodie Mob A 2020 Goodie Mob Prey -

Goodie Mob Album Featuring Ceelo Drops on Groupon

August 23, 2013 Goodie Mob Album Featuring CeeLo Drops on Groupon First Goodie Mob Album in 14 Years For Sale Today on Groupon.com CHICAGO--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Groupon (NASDAQ: GRPN) (http://www.groupon.com) today announces a deal for Goodie Mob's first album in 14 years. Groupon has a limited supply of Goodie Mob's new album, "Age Against the Machine," which officially releases from Primary Wave on Aug. 27. The CD is now available for purchase at Groupon.com for $8.99 at http://gr.pn/180qCBQ. The first single off the new Goodie Mob album is entitled, "Special Education," featuring Janelle Monae. The album also features T.I., and Goodie Mob's U.S. tour kicks off this weekend on Aug. 24 in Washington, with a special stop the following night in Brooklyn, N.Y. for a post-VMAs concert at Brooklyn Bowl. Goodie Mob's last released single was "Fight To Win," in the summer of 2012, an anthem of liberation, motivation and determination to always fight to win in life, a motto that the Goodie Mob lives by. Also, CeeLo Green's memoire, "Everybody's Brother," releases Sept. 10. In addition to the new album, tour and book, CeeLo and Goodie Mob will be the subjects of a new reality series to debut in 2014. Goodie Mob is a pioneering Southern hip-hop group and one of the most celebrated rap acts to come out of the hip-hop hotbed of Atlanta. Formed in 1991, Goodie Mob's original and current group members include CeeLo Green, Big Gipp, Khujo and T-Mo, all of whom grew up together in Atlanta alongside the rest of the Dungeon Family—the musical collective of Southern rappers, which includes Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast, Organized Noise and Parental Advisory. -

WAV / Kotori Magazine Issue 6 the Prodigy Dilated Peoples George

WWW.KOTORIMAG.COM MAGAZINE WWW.KOTORIMAG.COM MAGAZINE TM MUSIC/ART/POLITICS/CULTURE MUSIC/ART/POLITICS/CULTURE 006 / THE PRODIGY DILATED PEOPLES - GEORGE CLINTON FLIGHT COMICS - METRIC - SASHA & DIGWEED GRAM RABBIT MALKOVICH MUSIC DJ MUGGS PORTUGAL. THE MAN GOAPELE TIM FITE TWO GALLANTS USA $3.99 CANADA $4.99 ISSUE 6 SILVERSUN PICKUPS 0 6 0 74470 04910 4 BOMBAY DUB ORCHESTRA KOTORIMAG.COM RSE7!6SPRINGADPDF0- # - 9 #- -9 #9 #-9 + TABLE OF CONTENTS DILATED PEOPLES 12 They’re almost prophetic, hooking up with Kanye and Alchemist before most of the world even knew those names...now they’re back, and with 20/20, their vision is better than ever. Baby, Rakaa, and Evidence get all loose with our one and only Simonita. THE PRODIGY 40 Let the madness ensue as Maxim, Keith, and Liam reload The Prodigy cannon for another go round. Safety and sanity be damned. The electronic music world has never been the same since the Firestarter grabbed hold of us in the 90s. In this issue we explore the trials and tribs of megastardom and the never ending struggle to retain the punk rock performance belt they’ve been brandishing for years. GEORGE CLINTON 48 “Think! It ain’t illegal yet!!” That’s about the only venture outside the halls of justice that the P Funk Master has been able to afford of WOLFMOTHER late. Four score and seven lawyers later, the 08 man who fostered the groove for a nation of hip “You ever heard of Wolfmother?” ‘No.’ hop protagonists gets his pay day and let’s his “WOLFMOTHER WOLFMOTHER WOLF- story be told here in this exclusive interview. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 2-25-2000 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2000). The George-Anne. 1640. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/1640 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■H^MH ^^^^H^^H f a u J i h fi : 0 The Official Student Newspaper of Georgia Southern University ;.-,.•:. er' has it all: drops two to humor, wit and Alabama seriousness Charles Harper Webb gives us Eagles lose both games on poetry that is both poignant and the road 12-4 and 9-3 beautiful. during the week. Page 4 Page 6 Vol. 72 No. 61 Friday, February 25, 2000 Want to m Investors aren't the only ones who on it By Kathy Bourassa Don'tThe product was only available to people who Staff Writer agreed to sell the balls. For a little over a hundred their money. Valentine points out As you sort your mail an envelope catches your dollars, investors received two laundry balls, adver- banks have collapsed in the U.S. attention. There is no return address but the postmark tising pamphlets, and an explanation of the "pay- abroad, leaving customers hold- indicates that it originated from another state. -

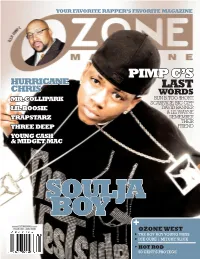

PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR

OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR. COLLIPARK BUN B, TOO $HORT, SCARFACE, BIG GIPP LIL BOOSIE DAVID BANNER & LIL WAYNE REMEMBER TRILL N*GGAS DON’T DIE DON’T N*GGAS TRILL TRAPSTARZ THEIR THREE DEEP FRIEND YOUNG CASH & MIDGET MAC SOULJA BOY +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS JANUARY 2008 ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE OZONE MAG // YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S LAST WORDS SOULJA BUN B BOY TOO $HORT CRANKIN’ IT SCARFACE ALL THE WAY BIG GIPP TO THE BANK WITH DAVID BANNER MR. COLLIPARK LIL WAYNE FONSWORTH LIL BOOSIE’S BENTLEY JEWELRY CORY MO 8BALL & FASCINATION MORE TRAPSTARZ SHARE THEIR THREE DEEP FAVORITE MEMORIES OF THE YOUNG CASH SOUTH’S & MIDGET MAC FINEST HURRICANE CHRIS +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE 8 // OZONE WEST 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 0 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden features ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson 54-59 YEAR END AWARDS PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul 76-79 REMEMBERING PIMP C MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad Sr. 22-23 RAPPERS’ NEW YEARS RESOLUTIONS LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. 74 DIRTY THIRTY: PIMP C’S GREATEST HITS SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Bogan, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, Destine Cajuste, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. -

Outkast Idlewild Album Download Zip Outkast Idlewild Album Download Zip

outkast idlewild album download zip Outkast idlewild album download zip. 1) Select a file to send by clicking the "Browse" button. You can then select photos, audio, video, documents or anything else you want to send. The maximum file size is 500 MB. 2) Click the "Start Upload" button to start uploading the file. You will see the progress of the file transfer. Please don't close your browser window while uploading or it will cancel the upload. 3) After a succesfull upload you'll receive a unique link to the download site, which you can place anywhere: on your homepage, blog, forum or send it via IM or e-mail to your friends. Outkast idlewild album download zip. “Take a little trip, hater pack up yo' mind, look forward not behind, then you'll see what you find” OutKast “Big Boi and Dre Present… Outkast” (2001) Tracks. Funkin' Around (previously unreleased) So Fresh, So Clean. The Whole World (featuring Killer Mike; previously unreleased) Elevators (Me & You) Git Up, Git Out (Remix) Movin' Cool (The After Party) (featuring Joi; previously unreleased) OutKast‘s first greatest hits album. Release date: December 4, 2001. Big Boi and Dre Present… OutKast is the first OutKast greatest hits album, released on Arista Records in 2001. The compilation consists of five tracks from Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, one from ATLiens, and three each from the break-out albums Aquemini and Stankonia. Outkast. ALBUM: Outkast – Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik Zip “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” is another brand new Album by “Outkast” Stream & Download “ALBUM: Outkast – Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” “Mp3 Download”. Stream And “Listen […] ALBUM: Outkast – Speakerboxxx/The Love Below. -

![28 Onions"] You Know This Groove, Don’T You? Most Everybody Knows It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1243/28-onions-you-know-this-groove-don-t-you-most-everybody-knows-it-2261243.webp)

28 Onions"] You Know This Groove, Don’T You? Most Everybody Knows It

The Bitter Southerner Podcast An Uncloudy Day [The Drive By Truckers: "Ever 0:00:00 South"] Welcome to “The Bitter Southerner Podcast” from Georgia Public Broadcasting and the magazine I edit, “The Bitter Southerner.” My name is Chuck Reece Chuck Reece. And this is the very first of six episodes that will make up season one of this podcast. Just a note before we begin, there is a little bit of explicit language. [Booker T. & The MGs: "Green 0:00:28 Onions"] You know this groove, don’t you? Most everybody knows it. But when I ask people, “who made the record?” I usually get blank stares. Well, the name of the song is “Green Onions,” and the band is Booker T. & the MGs. And to me, the MGs Chuck Reece exemplified the very best of Southern culture. They represented what happens when Southerners are willing to cross the barriers of race and class that have kept our region’s people apart for so long. In 1962, four young men in Memphis-- two white and two black-- formed Booker T. & the 0:01:04 MGs, and they became the house band at a studio called Stax Records. [Booker T. & The MGs: "Green Onions"] So, every time you’ve shaken your booty to Otis Redding or Wilson Pickett or Sam & Dave, you were shaking it to the MGs. Back then, the Jim Crow South wouldn’t let the MGs have a meal together in public, but so 0:01:26 Chuck Reece be it. Booker T. Jones, Steve Cropper, Al Jackson, and “Duck” Dunn ignored the color lines and the cultural barriers, at their personal peril, because they knew they had it in them to make something beautiful.