6 on the Place-Name Isle of Dogs Laura Wright University of Cambridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Ocpssummer2012 2

Old Chiswick Protection Society Summer 2012 Newsletter Chairman's message It has been a very busy period for the OCPS. Highlights include persuading stakeholders that the historic pollarding of the Eyot ought to continue. Our next aim is to extend the boundaries of the Conservation Area to include the Eyot, which was inexplicably excluded on first designation. The improvement in the physical condition of the York stone pavements is pleasing, as well as the sensitive replacement of lamps in the Conservation Area. The underpasses are also looking better and are set to improve. The committee is rightfully proud of its living oral history project, which seeks to ensure the memories and voices of the area do not slip from memory. Because of our disappointment at the result of Chiswick Lodge, we need to be at the heart of creating a Neighbourhood Plan for the area to ensure that future developments are properly scrutinised at all levels to harmonise with the character and appearance of the area. In the past OCPS has been able to punch well above its weight, but we need to increase our membership so that we are a stronger and more representative organisation. Remember we seek to protect the whole of the Conservation Area, which runs from British Passage in the east to St Mary’s Convent in the west, from the river in the south, to the A4 in the north. Proper representation from all parts of the area is essential. To this end, if you are not yet a member, please join and have your say on what shapes one of the UK’s oldest Conservation Areas. -

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

Household Income in Tower Hamlets 2013

October 2013 Household income in Tower Hamlets Insights from the 2013 CACI Paycheck data 1 Summary of key findings The Corporate Research Team has published the analysis of 2013 CACI Paycheck household income data to support the Partnerships knowledge of affluence, prosperity, deprivation and relative poverty and its geographical concentration and trends in Tower Hamlets. The median household income in Tower Hamlets in 2013 was £ 30,805 which is around £900 lower than the Greater London average of £ 31,700. Both were considerably above the Great Britain median household income of £27,500. The most common (modal) household annual income band in Tower Hamlets was £17,500 in 2013. Around 17% of households in Tower Hamlets have an annual income of less than £15,000 while just below half (48.7%) of all households have an annual income less than £30,000. 17% of Tower Hamlets households have an annual income greater than £60,000. 10 out of the 17 Tower Hamlets wards have a household income below the Borough’s overall median income of £30,805. The lowest median household income can be found in East India & Lansbury (£24,000) and Bromley by Bow (£24,800) while the highest is in St Katherine’s & Wapping (£42,280) and Millwall (£43,900). 2 1 Tower Hamlets Household income 1 1.1 CACI Paycheck household income data – Methodology CACI Information Solutions,2 a market research company, produces Paycheck data which provides an estimate of household income for every postcode in the United Kingdom. The data modelled gross income before tax and covered income from a variety of sources, including income support and welfare. -

Old Chiswick Protection Society

Old Chiswick Protection Society Autumn 2020 Newsletter Old Chiswick Protection Society exists to preserve and enhance the amenities of this riverside conservation area. Even the geese are social distancing! [Photograph: David Humphreys] Chairman’s Message As we look back at the last months, the Old Chiswick Conservation Area has become even more precious to many of us who live here, work here or visit. We have seen and spoken with visitors, previously unfamiliar with our environment and its atmosphere and history, who are enjoying it for the first time. Nature carries on here regardless, and our history continues to be relevant and vital to our future. We can't take anything for granted though. It is only with the support of our members' subscriptions and diligent work that we are here today and can be so proud of what has been achieved by the charity over the last 60 years. Old Chiswick could so easily have looked and felt very different: no Chiswick Eyot, with its unique withy beds and nature reserve; houses where Homefields Recreation Ground South is; an entirely different main road into and out of London, sacrificing more historical buildings; post-war housing instead of Georgian houses along Chiswick Mall. Our community has done much to help others this year, and we continue to build relationships with those like Asahi who are new to the area since taking over Fuller’s Brewery, and who have expressed a wish to become part of the community. We look forward to inviting you to join our AGM this year, which will of course be conducted on line, with the very latest advice on meetings. -

Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events

November 2016 Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events Gilbert & George contemplate one of Raju's photographs at the launch of Brick Lane Born Our main exhibition, on show until 7 January is Brick Lane Born, a display of over forty photographs taken in the mid-1980s by Raju Vaidyanathan depicting his neighbourhood and friends in and around Brick Lane. After a feature on ITV London News, the exhibition launched with a bang on 20 October with over a hundred visitors including Gilbert and George (pictured), a lively discussion and an amazing joyous atmosphere. Comments in the Visitors Book so far read: "Fascinating and absorbing. Raju's words and pictures are brilliant. Thank you." "Excellent photos and a story very similar to that of Vivian Maier." "What a fascinating and very special exhibition. The sharpness and range of photographs is impressive and I am delighted to be here." "What a brilliant historical testimony to a Brick Lane no longer in existence. Beautiful." "Just caught this on TV last night and spent over an hour going through it. Excellent B&W photos." One launch attendee unexpectedly found a portrait of her late father in the exhibition and was overjoyed, not least because her children have never seen a photo of their grandfather during that period. Raju's photos and the wonderful stories told in his captions continue to evoke strong memories for people who remember the Spitalfields of the 1980s, as well as fascination in those who weren't there. An additional event has been added to the programme- see below for details. -

Buses from North Greenwich Bus Station

Buses from North Greenwich bus station Route finder Day buses including 24-hour services Stratford 108 188 Bus Station Bus route Towards Bus stops Russell Square 108 Lewisham B for British Museum Stratford High Street Stratford D Carpenters Road HOLBORN STRATFORD 129 Greenwich C Holborn Bow River Thames 132 Bexleyheath C Bromley High Street 161 Chislehurst A Aldwych 188 Russell Square C for Covent Garden Bromley-by-Bow and London Transport Museum 422 Bexleyheath B River Thames Coventry Cross Estate The O2 472 Thamesmead A Thames Path North CUTTER LANE Greenwich 486 Bexleyheath B Waterloo Bridge Blackwall Tunnel Pier Emirates East india Dock Road for IMAX Cinema, London Eye Penrose Way Royal Docks and Southbank Centre BLACKWALL TUNNEL Peninsula Waterloo Square Pier Walk E North Mitre Passage Greenwich St George’s Circus D B for Imperial War Museum U River Thames M S I S L T C L A E T B A N I Elephant & Castle F ON N Y 472 I U A W M Y E E Thamesmead LL A Bricklayers Arms W A S Emirates Air Line G H T Town Centre A D N B P Tunnel Y U A P E U R Emirates DM A A S E R W K Avenue K S S Greenwich Tower Bridge Road S T A ID Thamesmead I Y E D Peninsula Crossway Druid Street E THAMESMEAD Bermondsey Thamesmead Millennium Way Boiler House Canada Water Boord Street Thamesmead Millennium Greenwich Peninsula Bentham Road Surrey Quays Shopping Centre John Harris Way Village Odeon Cinema Millennium Primary School Sainsbury’s at Central Way Surrey Quays Blackwall Lane Greenwich Peninsula Greenwich Deptford Evelyn Street 129 Cutty Sark WOOLWICH Woolwich -

Deptford Church Street & Greenwich Pumping Station

DEPTFORD CHURCH STREET & GREENWICH PUMPING STATION ONLINE COMMUNITY LIAISON WORKING GROUP 13 July 2021 STAFF Chair: Mehboob Khan Tideway • Darren Kehoe, Project Manager Greenwich • Anil Dhillon, Project Manager Deptford • Natasha Rudat • Emily Black CVB – main works contractor • Audric Rivaud, Deptford Church Street Site Manager • Anna Fish– Deptford Church Street, Environmental Advisor • Robert Margariti-Smith, Greenwich, Tunnel & Site Manager • Rebecca Oyibo • Joe Selwood AGENDA Deptford Update • Works update • Looking ahead • Noise and vibration Greenwich Update • Works update • Looking ahead • Noise and vibration Community Investment Community Feedback / Questions DEPTFORD CHURCH STREET WHAT WE’RE BUILDING DEPTFORD WORKS UPDATE SHAFT & CULVERT Shaft • Vortex pipe installed and secondary lining complete • Tunnel Boring Machine crossing complete • Vortex generator works on-going Culvert • Excavation complete • Base slab and walls complete • Opening to shaft complete DEPTFORD WORKS UPDATE COMBINED SEWER OVERFLOW (CSO) CSO Phase 1: Interception Chamber • Internal walls and roof complete • Mechanical, Electrical, Instrumentation, Controls, Automation (MEICA) equipment installation on-going CSO Phase 2: Sewer connection • Protection works of Deptford Green Foul Sewer complete • Secant piling works complete • Capping beam and excavation to Deptford Storm Relief Sewer on-going time hours: Monday to Friday: 22:00 to 08:00 DEPTFORD 12 MONTHS LOOK AHEAD WHAT TO EXPECT AT DEPTFORD CSO: connection to existing sewer Mitigations • This work will take place over a 10 hour shift – the time of the shift • Method of works chosen to limit noise will be dependent on the tidal restrictions in the Deptford Storm Relief Sewer’ generation such as sawing concrete into • Lights to illuminate works and walkways after dark blocks easily transportable off site. -

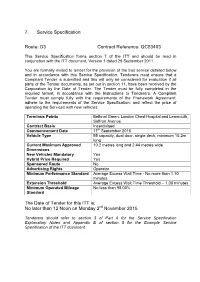

D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 the Date of Tender for This ITT Is

7. Service Specification Route: D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Bethnal Green, London Chest Hospital and Leamouth, Saffron Avenue Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 17th September 2016 Vehicle Type 55 capacity, dual door, single deck, minimum 10.2m long Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.44 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.10 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold – 1.00 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard The Date of Tender for this ITT is: nd No later than 12 Noon on Monday 2 November 2015 Tenderers should refer to section 3 of Part A for the Service Specification Explanatory Notes and Appendix B of section 5 for the Example Service Specification of the ITT document. -

BBB Ward Profile

Bromley-by-Bow Contents Page Population 2 Ward Profile Age Structure 2 Ethnicity 3 Religion 3 Household Composition 4 Health & Unpaid Care 5 Deprivation 8 Crime Data 9 Schools Performance 10 Annual Resident Survey 2011/12 summary 11 Local Layouts 12 Within your ward… 15 In your borough… 17 Data Sources 19 Bromley-by-Bow Page 2 Figure 2: Ward population density Population • At the time of the 2011 Census the population of Bromley-by-Bow was 14,480 residents, which accounted for 5.7% of the total population of Tower Hamlets. • The population density of the ward was 134.8 residents per hectare (74 square meters for each resident of the ward). This compares with a borough density of 129 residents per hectare and 52 per hectare in London. • There were 5,149 occupied households in this ward and an average household size of 2.81 residents; this is higher than the average size for Tower Hamlets of 2.47. Change Figure 3: Proportion of population by age 90+ • The population of Bromley-by-Bow increased by 25% between 2001 BBB Variance and 2011 which was lower than the borough average of 29.6%. 80 ‒ 84 LBTH • Over the next 10 years the population of the ward is projected to 70 ‒ 74 grow by 78% to 91%, reaching somewhere between 26,000 and Bromley-by- 27,800 residents by 2021. 60 ‒ 64 Bow 50 ‒ 54 Age Structure 40 ‒ 44 30 ‒ 34 Figure 1: Age Structure Residents by Age 0-15 16-64 65+ Total 20 ‒ 24 Bromley-by-Bow 3,871 9,776 833 14,480 Bromley-by-Bow % 26.7% 67.5% 5.8% 100% 10 ‒ 14 0 ‒ 4 Tower Hamlets % 19.7% 74.1% 6.1% 100% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 5% 10% 15% Bromley-by-Bow Page 3 Ethnicity Figure 4: Proportion of Residents by Ethnicity • The proportion of residents identifying as ‘White British’ in the 100% Census for Bromley-by-Bow was 21.5%, this was the lowest 8.0% 90% 19.2% Bangladeshi proportion of all wards. -

The British Golf the JOINT COUNCIL

JANUARY 1971 I/- The British Golf THE JOINT COUNCIL FOR GOLF GREENKEEPER APPRENTICESHIP Tomorrow's Greenkeepers are needed today. Training Apprentices on your golf course will ensure that the Greenkeeping skills of the past can help with the upkeep problems of the future. Hon. Secretary: W. Machin, Addington Court Golf Club, Featherbed Lane, Addington, Croydon, Surrey. THE BRITISH GOLF GREENKEEPER HON. EDITOR: F. W. HAWTREE No. 309 New Series JANUARY 1971 FOUNDED 1912 PUBLISHED MONTHLY FOR THE BENEFIT OF GREENKEEPERS. GREENKEEPING AND THE GAME OF GOLF BY THE BRITISH GOLF GREENKEEPERS' ASSOCIATION President: JANUARY CARL BRETHERTON Vice-Presidents: SIR WILLIAM CARR GORDON WRIGHT F. W. HAWTREE S. NORGATE CONTENTS I. G. NICHOLLS F. V. SOUTHGATE P. HAZELL W. KINSEY P. MARSHALL PAGE 3 TEE SHOTS W. PAYNE Chairman: A. ROBERTSHAW 2 West View Avenue 4 NOW THINGS ARE SMOOTH Burley-in-Wharfedale Yorks. Vice-Chairman: J. CARRICK 7 SPECIAL OCCASIONS Hon. Secretary & Treasurer: C. H. Dix Addington Court G.C. Featherbed Lane 8 SITUATIONS VACANT Addington, Croydon, Surrey CRO 9AA Executive Committee: Carl Bretherton (President) 10 FIRST YEAR OF RETIREMENT G. Herrington E. W. Folkes R. Goodwin S. Fretter J. Parker J Simpson A. A. Cockfield H. M. Walsh 11 WAR-TIME RULES OF GOLF H. Fry (Jun.) P. Malia Hon. Auditors: Messrs SMALLFIELD RAWLINS AND Co., Candlewick House, 116/126 13 NEWS FROM SECTIONS Cannon Street, London, E.C.4 Hon. Solicitors: HENRY DOWDING, LL.B. 203-205 High Street Orpington The Association is affiliated to the English and Welsh Golf Unions. EDITORIAL AND ADVERTISEMENT OFFICES: Addington Court Golf Club Featherbed Lane. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British