The Liability of an Undisclosed Principal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contractual Confusion—Assuming the Liability of Others

Contractual Confusion—Assuming the Liability of Others July 2009 by Craig F. Stanovich It is not surprising, then, if we become easily confused and "misremember" how contractual liability insurance works. For many, the subtleties of this rather arcane topic simply cannot be gleaned from the superficial and infrequent contacts we have with it; for others, it may not rank high on the excitement meter. Either way, what follows is intended to assist in understanding contractual liability insurance by thrashing out some concepts and offering some observations you may find helpful. Basis of Liability Liability can be imposed by law or by contract. You can also assume the liability of another. These are discussed below. Liability Imposed by Law The law can impose liability on us for our own actions . If we are negligent, we are personally liable for the damages that result. We can also be held liable for the actions of others . For example, if our employee is negligent while acting in the scope of employment, not only is the employee personally liable, we are also liable solely because we are the employer. Our liability is based entirely on our relationship with our employee. Assigning liability to an otherwise blameless party (the employer did nothing wrong) for the acts of another (our employee was negligent) is called "vicarious" liability and is also liability imposed by law. Although these concepts are generally well understood, both are worth repeating—to establish a baseline of comprehension and also to use as a point of comparison to help gain insight into contractual liability. -

Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: a Comment

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1996 Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: A Comment Eric A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eric Posner, "Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: A Comment," 144 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1971 (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORMS, FORMALITIES, AND THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS: A COMMENT ERIC A. POSNERt INTRODUCTION Jason Johnston's Article makes three contributions to the economics and sociology of contract law.' First, it provides a methodological analysis of the use of case reports to discover business norms. Second, it makes a positive argument about the extent to which businesses use writings in contractual relations. Third, it sets the stage for, and hints at, a normative defense of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) section 2-201. Although the first contribution is probably the most interesting and useful, I focus on the second and third, and comment only in passing on the first. I conclude with some observations about the role of formalities in contract law. I. JOHNSTON'S POSITIVE ANALYSIS A. The Hypothesis Johnston's hypothesis is that "strangers" use writings for the purpose of ensuring legal enforcement. "Repeat players" do not use writings for this purpose because they expect that nonlegal sanctions will deter breach. -

Vicarious Liability Vs Principal's Liability

Vicarious liability vs Principal’s liability When undertaking any construction project Principal Unless the risk profile of the project dictates otherwise, clients need to carefully assess whether their potential most of the time the contractor would arrange public liabilities arising out of the project are adequately covered liability insurance for small to medium sized projects to by insurance. This paper discusses the insurance options cover the insured parties’ legal liability to third parties, available to principals, potential uninsured exposures arising out of the performance of the contract works. certain insurance options can leave and the steps principals Contractors would typically already have an annual general may need to take to fill these exposure gaps. liability policy which can be relied upon. For major projects, it is likely that the suite of insurance Unless the risk profile of the project dictates otherwise, covers will be arranged either under an owner/principal most small to medium projects allow the contractor to controlled insurance programme or a contractor arrange public liability insurance. This typically means controlled insurance programme. However, for small to that the contractor will rely on their annual public liability medium projects, insurance responsibilities are often policy and the principal can be included as an “additional shared between the parties and cover is placed by those insured” (for their vicarious liability only) arising out of considered best suited to arrange and manage the relevant the performance of the contract works by the contractor. covers. In the situation where a contractor arranges public Despite having liability insurance, principals will need to assess the level of this cover in place, coverage available, and to consider what exposures may there are a number There are a number of other still exist that are not contractually required to be covered of other liabilities liabilities a principal could face by the contractor’s policy. -

Electronic Seal Certificates

Certification Policy Electronic Seal Certificates Version: 190507 Classification: Public Certification Policy Electronic Seal Certificates Version history Version Section and changes Date of publication 190121 ● New Certification Policy for Electronic Seal 21/01/2019 Certificates that groups together all existing policies regarding this type of certificate. May be consulted at http://firmaprofesional.com/cps 190507 ● Homogenization of the terminology of Public 07/05/2019 Administration Seal. ● Period of validity of Public Administration Seal certificates increased from 3 to 5 years. ● Validation of applicant’s email before issuing the certificate. ● Changed the CA that issues the Public Administration Seal to “AC Firmaprofesional - CUALIFICADOS”. Page 2 of 12 Certification Policy Electronic Seal Certificates Index 1. Introduction 4 1.1. General description 4 1.2. Identification of the Document 5 2. Participating entities 6 2.1. Certification Authorities (CA) 6 2.2. Registration Authority (RA) 6 2.3. Applicant 6 2.4. Subscriber 7 2.5. Third parties trusting in certificates 7 3. Certificate features 7 3.1. Certificate Validity Period 7 3.2. Specific use of certificates 8 3.2.1. Appropriate use of certificates 8 3.2.2. Non authorised use of certificates 8 3.3. Rates 8 4. Operations procedures 9 4.1. Certificate issuance process 9 4.2. Certificate revocation 11 4.3. Certificate renewal 11 5. Certificate profiles 12 Page 3 of 12 Certification Policy Electronic Seal Certificates 1. Introduction 1.1. General description Firmaprofesional issues this Certification Policy for Electronic Seal Certificates, grouping together distinct policies that defines certificates intended to sign, on behalf of the organization or body, electronic documents automatically under the responsibility of the certificate subscriber. -

Module Cuzl331 Commercial Law 1: Agency and Sales

MODULE CUZL331 COMMERCIAL LAW 1: AGENCY AND SALES Maureen Banda-Mwanza LLB (UNZA), ACIArb ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the formulation of this module, tailored for the exclusive use of Cavendish University, the Author referred to various renown Commercial law books, quotations of which shall be minimized as much as is practicable. The good authors of the renowned works aforementioned are fully acknowledged for the relevance of their various pieces of work in the study of Commercial Law. CONTENTS PAGE TOPIC 1 TOPIC 1 AGENCY AT the end of this unit, students should be able to understand: 1. The requirements in forming an agency contract, formalities and capacity, 2. Authority of an agent 3. The duties of an agent 4. The Agent’s right against the Principal 5. The Principal’s relation with third parties 6. Various types of agency 7. How to terminate an Agency agreement Introduction Agency is one of the essential features of Commercial law. Commercial law is the law governing business contracts, bankruptcy, patents, trade-marks, designs, companies, partnership, export and import of merchandise, affreightment, insurance, banking, mercantile agency and usages. Agency can therefore be defined in the relationship which arises when one person (an agent) acts on behalf of another person (the principal) in a manner that the agent has power to affect the principal’s legal position with regard to a third-party. Common law explains the basic rule of an agency relationship in the Latin maxim “Qui facit per alium, facit per se” the literal English translation of which is he who acts by another acts by himself. -

Vicarious Liability Critique and Reform

Vicarious Liability Critique and Reform Anthony Gray HART PUBLISHING Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House , Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford , OX2 9PH , UK HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 Copyright © Anthony Gray , 2018 Anthony Gray has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3 ) except where otherwise stated. All Eur-lex material used in the work is © European Union, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/ , 1998–2018. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Names: Gray, Anthony (Law teacher) Title: Vicarious liability : critique and reform / Anthony Gray. -

Commercial Invoice

Commercial Invoice Sent by AWB No Company name Invoice No Name/department Number of pieces Address Total gross weight Total net weight Telephone Carrier E-mail VAT registration No Buyer Delivery to (if different from the buyer) Company name Company name Name/department Name/department Address Address Telephone Telephone E-mail E-mail VAT registration No VAT registration No Full description of goods Customs Country Quantity/ Unit value Sub total commodity of Number of and value and code origin units currency currency Total value and currency Reason for export Terms of delivery I declaire that the above information is true and correct to the best of my knowledge. Date Name Signature How to fill in a Commercial Invoice A correctly completed Commercial invoice is the best guarantee of successful customs clearance. The Commercial invoice should be typed in the receiving country’s language or in English and four signed copies should be enclosed with the shipment. A Commercial invoice should be used when the product is to be sold in the destination country. A Proforma invoice should be used when the product is not to be sold (e.g. it is a gift, a repair or a loan between companies). We recommend that you use your company’s official invoice if available. Sent By Customs Commodity Code Fill in the sender’s/selling company’s name, contact person, Customs commodity code, used for clearance in the address and registration/organization number. destination country. You can find more information about commodity codes from your own country’s customs Buyer webpage. Fill in the buyer’s name, contact person, address and registration/organization number. -

Singapore Court of Appeal Clarifies Requirements on Execution of Deeds

CASEWATCH MARCH 2021 Singapore Court of Appeal Clarifies Requirements on Execution of Deeds The Singapore Court of Appeal has affirmed that sealing remains a key requisite for the execution of a deed, which is valid by being “signed, sealed and delivered”: Lim Zhipeng v Seow Suat Thin and another matter [2020] SGCA 89 (“Lim Zhipeng”). Our Comments Lim Zhipeng is significant as the Court of Appeal has clarified that sealing remains a crucial requirement for construing that a deed has been validly executed, and notwithstanding developments in the common law that have expanded the scenarios under which a document has been proved to be executed under seal, the court will look beyond the words of the document referring to it as having been sealed. While a seal may not need to take the form of wax (as was historically used) or the circular wafer seal commonly used nowadays, the Court of Appeal has held that there must be evidence of a party’s intention in sealing the document beyond using in the document the words “executed as a deed” and the parties’ signing next to the words “signed, sealed and delivered”. In Lim Zhipeng, the Court of Appeal explored cases where the requirement of sealing was satisfied by green ribbon attached to a document evidencing where a physical seal should have been together with certificates certifying the document was a deed and a printed circle with the letters ‘L.S.’ within it countersigned by the executing party, which evidenced parties’ intention to seal the document they were signing. In the modern day, a physical manifestation of a seal could be represented by an electronic red seal similar to the circular wafer seal commonly stuck onto documents to meet the requirements of sealing. -

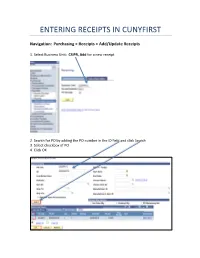

Entering Receipts in Cunyfirst

ENTERING RECEIPTS IN CUNYFIRST Navigation: Purchasing > Receipts > Add/Update Receipts 1. Select Business Unit: CSIPR, Add for a new receipt 2. Search for PO by adding the PO number in the ID field and click Search 3. Select checkbox of PO 4. Click OK FOR “AMOUNT ONLY” PO’S: 5. Enter price shown on invoice 6. Click save Note: amount only PO’s will default to original PO amount. This number must be changed to match the invoice FOR “QUANTITY BASED” PO’S: 5. Enter the quantity received 6. Click save Note: record the number of good received per line in quantity PO’s. You will not see the amount originally ordered Received status displays and assigns a Receipt ID which should be retained for your records If an inspection is required a box will pop up notifying the receiver that they must contact the inspector with the receipt number so they can complete an inspection receipt 7. Click on Add Comments and add attachments (signed and dated packing slips or invoices) Enter PO number in comments 8. Click on Header Details to modify receipt date 9. Change receipt date to reflect the date goods or services were received per packing slips, invoices or dates of service which should be the same date on attached backup. Note: receipt date will default to current date if no changes are made. 10. Click on Document Status to view related documents 11. Print a screen shot of the Receipt, sign and date it, attach all original documentation with the receipt number and PO number on and forward it to Accounts Payable Summary: 1. -

Commercial Invoice Why Do You Need to Complete a Commercial Invoice? INVOICE

INVOICE Everything you need to know about completing a commercial invoice Why do you need to complete a commercial invoice? INVOICE • It is the basis for your customs declaration. • It clearly describes the goods and their value. • It helps to determine customs duties to be paid. • It helps you to avoid any customs delays and deliver your shipment smoothly. • Without a commercial invoice, you are unable to ship overseas. General tips for completing a commercial invoice INVOICE Three signed copies – one original and two copies – are required and should You should prepare a commercial Be accurate and provide as be included with your shipment. invoice in advance of your much detail about the goods x3 Make sure you also keep a copy of the shipment collection that you’re exporting orginal signed commercial invoice for your own records When possible, include a Ensure that you have clearly harmonized tariff code. This global stated your reason for system of classification speeds up exporting on the document, exports, reduces delays and can e.g. gift help you avoid any additional fees You can download a or charges commercial invoice on UPS.com Check the tariff code here ? DOWNLOAD Menu The commercial invoice Click on the yellow squares to go through each section of the invoice. Click on the home button to go back to the menu. From From Make sure to include full details, including: • Tax ID (or in the EU, the Economic Operators Registration and Identity (EORI) Number) • Shipper’s contact name • Shipper’s address with postal code and country • Shipper’s phone number (very important) Shipment Details Shipment Details Tracking . -

Law Reform Commission of British Columbia Report on Deeds and Seals

LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT ON DEEDS AND SEALS LRC 96 JUNE, 1988 The Law Reform Commission of British Columbia was established by the Law Reform Commis- sion Act in 1969 and began functioning in 1970. The Commissioners are: ARTHUR L. CLOSE, Chairman HON. RONALD I. CHEFFINS, Q.C., Vice-Chairman MARY V. NEWBURY LYMAN R. ROBINSON, Q.C. PETER T. BURNS, Q.C. Thomas G. Anderson is Counsel to the Commission. J. Bruce McKinnon, Deborah M. Cumberford and Monika Gehlen are Legal Research Officers to the Commission. Sharon St. Michael is Secretary to the Commission Text processing and technical copy preparation by Linda Grant. The Commission offices are located at Suite 601, Chancery Place, 865 Hornby St., Vancouver, BC V6Z 2H4. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Law Reform Commission of British Columbia Report on deeds and seals “LRC 96" Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-7718-8679-9 1. Deeds - British Columbia. 2. Seals (Law) - British Columbia. I. Title DEB231.A72L37 1988 346.711'02 C88-092150-1 Table of Contents I. DEEDS AND SEALS 1 A. Introduction 1 B. Background to the Report 2 C. A Note on Terminology 2 D. Overview of the Report 2 E. The Working Paper 2 II. HISTORICAL NOTE 3 A. Introduction 3 B. Execution of Documents and Literacy 3 C. Actions of Covenant 4 D. Assumpsit and the Decline of Covenant 5 E. Covenant Today 5 III. THE MAKING OF A DEED 7 A. Introduction 7 B. Form and Material Substance 7 1. Introduction 7 2. The Need for an Attachment, Mark or Impression 7 3. -

A Theory of Vicarious Liability 287

A Theory of Vicarious Liability 287 A Theory of Vicarious Liability J.W. Neyers* This article proposes a theory' of vicarious liability Cet article propose une thiorie de la responsabilite which attempts to explain the central features and du fail d'autrui qui essaie d'expliquer les limitations of the doctrine. The main premise of the caracteristiques el les limitations centrales de la article is that the common law should continue to doctrine. La principale primisse de cet article eslque impose vicarious liability because it can co-exist with la « common law » doit continuer a imposer la the current tort law regime that imposes liability for responsabilite du fait d'autrui parce qu'elle peul fault. The author lays out the central features of the coexisler avec le regime actual de la responsabilite doctrine of vicarious liability and examines why the delictuelle qui impose la responsabilite' pour fauie. leading rationales (such as control, compensation, L 'auteur e'nonce les caracteristiques centrales de la deterrence, loss-spreading, enterprise liability and doctrine de la responsabilite du fait d'autrui et mixed policy) fail to explain or account for its examine les raisons pour lesquelles les principaux doctrinal rules. motifs (comme le controle. I'indemnisation. la The author offers an indemnity theory for vicarious dissuasion. I'etalement des penes, la responsabilite liability and examines why the current rules of d'entreyirise et la police mate) ne peuvenl m vicarious liability are limited in application to expliquer nijuslifier les regies de cette doctrine. employer-employee relationships and do not extend L 'auteur propose une thiorie des indemnltis pour la further.