Representing Slavery at Oakland Plantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDWARD J. GAY and FAMILY PAPERS (Mss

EDWARD J. GAY AND FAMILY PAPERS (Mss. 1295) Inventory Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Reformatted 2007-2008 By John Hansen and Caroline Richard Updated 2013 Jennifer Mitchell GAY (EDWARD J. AND FAMILY) PAPERS Mss. # 1295 1797-1938 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, LSU LIBRARIES CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SERIES ............................................................................................................................ 7 Series I., Correspondence and Other Papers, 1797-1938, undated ................................................. 8 Series II., Printed Items, 1837-1911, undated ............................................................................... 58 Series III., Photographs, 1874-1901, undated. .............................................................................. 59 Series IV. Manuscript Volumes, 1825-1919, undated. ................................................................ 60 CONTAINER LIST ..................................................................................................................... -

Designing Parterres on the Main City Squares

https://doi.org/10.24867/GRID-2020-p66 Professional paper DESIGNING PARTERRES ON THE MAIN CITY SQUARES Milena Lakićević , Ivona Simić , Radenka Kolarov University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Agriculture, Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Novi Sad, Serbia Abstract: A “parterre” is a word originating from the French, with the meaning interpreted as “on the ground”. Nowadays, this term is widely used in landscape architecture terminology and depicts a ground- level space covered by ornamental plant material. The designing parterres are generally limited to the central city zones and entrances to the valuable architectonic objects, such as government buildings, courts, museums, castles, villas, etc. There are several main types of parterres set up in France, during the period of baroque, and the most famous one is the parterre type “broderie” with the most advanced styling pattern. Nowadays, French baroque parterres are adapted and communicate with contemporary landscape design styles, but some traits and characteristics of originals are still easily recognizable. In this paper, apart from presenting a short overview of designing parterres in general, the main focus is based on designing a new parterre on the main city square in the city of Bijeljina in the Republic of Srpska. The design concept relies on principles known in the history of landscape art but is, at the same time, adjusted to local conditions and space purposes. The paper presents the current design of the selected zone – parterre on the main city square in Bijeljina and proposes a new design strongly influenced by the “broderie” type of parterre. For creating a new design proposal we have used the following software AutoCad (for 2D drawings) and Realtime Landscaping Architect (for more advanced presentations and 3D previews). -

Nottoway-Plantation-Resort-Brochure

Explore ... THE GRANDEUR & THE STORIES OF NOTTOWAY. Guided tours of the mansion Guided Mansion Tours are offered 7 days a week. Completed in 1859, Nottoway’s Self-guided tours of the grounds, museum & theater spectacular 53,000 square foot are also available daily. mansion was built by sugar- cane magnate John Hampden Randolph for his wife and their 11 children. Known for its stunning architectural design, elaborate interiors and innovative features, this majestic “White Castle” continues to captivate visitors from around the world. Experience the grandeur and unique charm that sets this plantation apart. Let our tour guides regale you with the fascinating stories and history of Nottoway, the grandest antebellum mansion in the South to survive the Civil War. www.nottoway.com Louisiana’s Premier Historical Resort Nottoway Plantation & Resort Room Reservations 31025 Hwy. 1 • White Castle, LA 70788 · Online at www.nottoway.com Ph: 866-527-6884 · 225-545-2730 · Or call 866-527-6884 (toll-free) Fax: 225-545-8632 or 225-545-2730 (local) www.nottoway.com Restaurant Reservations Facilities · Online at www.seatme.com · AAA Four Diamonds Award · National Register of Historic Places · 40 elegantly appointed accommodations ◦ 7 bed & breakfast-style rooms ◦ 28 deluxe rooms ◦ 3 corporate cottage suites ◦ 2 honeymoon suites · All non-smoking rooms · Handicap-accessible rooms · Mansion Restaurant & Bar/Lounge · Le Café · Fitness Center with lounge, TV, pool table · Business Center · Guided & self-guided tours · Museum & theater, historical cemetery · Gift shop · On-site salon: hair, nails, massage · Outdoor pool and cabana with hot tub · The Island Golf Club - 10 minutes away Location · Ample free parking Centrally located between Louisiana’s · Buses welcome · Special group rates 3 major metropolitan cities, New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Lafayette. -

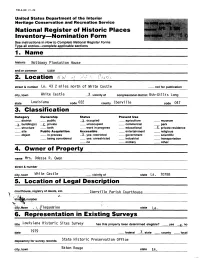

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name__________________ historic Nottoway Plantation House________________ and/or common same 2. Location A/ v street & number La. 43 2 miles north of White Castle not for publication city,town White Castle ________JL vicinity of____congressional district 8th-Gi 11 i S Long state Louisiana code 022 county Iberville Code 047 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational _ X_ private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other- 4. Owner of Property name Mrs. Odessa R. Owen street & number city,town whi te Castle vicinity of state La. 70788 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Iberville Parish Courthouse number \ sPlaquemine state La. 6. Representation in Existing Surveys tjtle Louisiana Historic Sites Survey has this property been determined elegible? no date 1979 federal X state __ county local depository for survey records state Historic Preservation Office city, town Baton Rouge state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered 0(_ original site __ ruins X altered __ moved date fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Nottoway plantation house is set approximately 200 feet behind the Mississippi River levee, two miles north of the town of White Castle. -

2019 Annual Report

The Friends of The Frelinghuysen Arboretum 2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT In April 2019 I was asked to make a presentation to the Morris County Park Commissioners about “who the Friends of Frelinghuysen Arboretum are and what they do.” Barbara Shepard, President of the MCPC Board, noted that there were several new commissioners who did not know much about the Frelinghuysen Arboretum (FA) and its support group. This request motivated me to combine the highlights of the Friends’ history (from a draft by past President Sally Hemsen) with a summary of the Friends’ financial contributions to the MCPC since inception in 1973, with some amazing results. The Friends’ grants and donations to the MCPC can be broadly categorized as support for Facilities (Frelinghuysen, Bamboo Brook, Willowwood, and Tourne Park), Plants & Gardens, Programs & Events, and Staff Support. To cite some major support for Facilities, the Friends gave (in round numbers) $50,000 for the renovation of the Haggerty Education Center auditorium and lobby, $156,000 for garden infrastructure projects at the FA, $40,000 for preservation of the Rare Books collection, and $55,000 for the hardscape restoration at Bamboo Brook, to name just a few from a total of nearly $450,000. Donations for Plants & Gardens were $31,000; for Programs & Events--$81,000; and for Staff Support--$137,000. Total grants and donations since 1973 were nearly $700,000, and this figure does not include support for several staff positions through the years, nor the scholarships which have been presented annually since 1977. The actual total is probably close to $1 million. -

View This Finding

See also UPA Microfilm MF 5322, Series I, Part 1, Reels 14-15 JOHN H. RANDOLPH PAPERS Mss. 355, 356 Inventory Compiled by Kevin Shupe Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1988 Revised 2009 Updated 2020 RANDOLPH (JOHN H.) PAPERS Mss. 355, 356 1823-1890 LSU LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SUBGROUPS AND SERIES ......................................................................................... 7 SUBGROUPS AND SERIES DESCRIPTIONS ............................................................................ 8 INDEX TERMS ............................................................................................................................ 10 CONTAINER LIST ...................................................................................................................... 11 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please place a request via the Special Collections Request System. Consult the Container List for location information. Photocopying. Should you wish to request -

Management Plan / Environmental Assessment, Atchafalaya

Atchafalaya National Heritage Area Heritage National Atchafalaya COMMISSION REVIEW- October 1, 2010 Vol. I SEPTEMBER 2011 Environmental Assessment Environmental Management Plan Note: This is a low resolution file of the painting, “Hope” to show artwork and placement. Artwork will be credited to Melissa Bonin, on inside front cover. AtchafalayaAtchafalaya NationalNational HeritageHeritage AreaArea MANAGEMENT PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT SEPT DRAFT MANAGEMENT PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 2011 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. Front cover photo credit: Louisiana Office of Tourism NPS ABF/P77/107232 SEPTEMBER 2011 Printed on recycled paper July 1, 2011 Dear Stakeholders: I am pleased to present the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area Management Plan and Environmental Assessment developed by the Atchafalaya Trace Commission. The Plan is a model of collaboration among public agencies and private organizations. It proposes an integrated and cooperative approach for projects that will protect, interpret and enhance the natural, scenic, cultural, historical and recreational resources of the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area. -

Rethinking Representations of Slave Life a Historical Plantation Museums

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Rethinking representations of slave life a historical plantation museums: towards a commemorative museum pedagogy Julia Anne Rose Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Julia Anne, "Rethinking representations of slave life a historical plantation museums: towards a commemorative museum pedagogy" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1040. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1040 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RETHINKING REPRESENTATIONS OF SLAVE LIFE AT HISTORICAL PLANTATION MUSEUMS: TOWARDS A COMMEMORATIVE MUSEUM PEDAGOGY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Julia Anne Rose B.A., State University of New York at Albany, 1980 M.A.T., The George Washington University, 1984 August, 2006 Dedication In memory of my loving sister, Claudia J. Liban ii Acknowledgments I was a young mother with two little boys when I first entertained the idea of pursuing a doctor of philosophy degree in education. -

History of Gardening

Hist ory of Gardening 600-850 HE COLOR OF RIPE TOMATOES, the juicy tang of a peach, the Tgreen evenness of a lawn, the sweet scent of lilies and lilacs… Summer is the time for gardeners, and this exhibit celebrates the season with a select ion of books on several diff erent types of garden- ing. From antiquity to the present, interest in gardens has generated a steady supply of books on plants, planting advice, and landscape design. Th is exhibit focuses on gardening in the seventeenth, eigh- teenth, and nineteenth centuries, taking into account formal es- tate gardens, kitchen gardens, tree nurseries, and other plantings. Gardeners during this period ranged from aristocratic hobbyists and landowners to the more humbly born professional grounds- keepers hired to manage estates both great and small. Hybridizers and botanists introduced exciting new varieties of fruits, vegetables, and fl owers into gardens across the Europe and the Americas. In England, fi gures like “Capability” Brown and Humphry Repton made names for themselves as landscape architect s on a grand scale, while botanists and nurserymen like William Curtis and Leonard Meager contributed to the gardener’s stock of pract ical information on specifi c plants. From the proper way to prune fruit trees to the fashionable layout of a great estate, these books record how gardeners select ed, planned, and cared for their plantings. Viewers are invited to read, enjoy, and imagine the colors, fl avors, sights and smells of summers long past. e Kitchen Garden ITCHENITCHEN gardens were the heart of rural food produc- Ktion, wherewhere everythingeverything fromfrom the tenderesttenderest peaches and plums to the hardiest cabbage and kale were grown. -

America's Deep South

8 DAY HOLIDAY America’s Deep South featuring New Orleans, Natchez and a Nottoway Plantation Stay April 1, 29; May 27; October 21, 28 2018 Departure Dates: America’s Deep South The beauty and charm of Amer- ica’s8 Days Deep • South14 Meals comes alive on a tour that combines the best of New Orleans and Natchez with a stay at Nottoway Plantation Resort. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS 4 14 Meals (5 dinners, 2 lunches and 7 breakfasts) 4 Round trip airport transfers 4 Spend 3 nights in “The Big Easy,” New Orleans 4 Enjoy dinner and fun at the New Orleans School of Cooking 4 Narrated New Orleans sightseeing tour with a local guide including Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, the Garden District and the French Quarter 4 Enjoy brunch and live music on a Jazz Brunch cruise 4 Visit the National WWII Museum, dedicated to the victory by the Allies in World War II 4 Learn the secrets to float building at Mardi Gras World and enjoy New Orleans School of Cooking dinner at the famed Court of Two Sisters 4 Take a narrated swamp tour and visit the impressive Oak Alley Plantation 4 DAY 1 – Arrive in Louisiana Spend 1 night at Nottoway Plantation Resort with included dinner Welcome to the beautiful South. Arrive in New Orleans by 3:00 p.m. and home tour 4 and transfer to our hotel. Tonight get to know your traveling com- Visit Jefferson Davis’ boyhood home, Rosemont panions and learn the basics of Louisiana cooking from well-known 4 Tour 2 of Natchez’s impressive homes, the 1860 and the Longwood local chefs while enjoying dinner at the New Orleans School of Greek Revival Stanton Hall Cooking. -

New French Formal Gardens

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 I - HISTORY .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1 - The Château’s Surroundings in the 16 th Century ........................................................................ 4 2 - The Major Projects of the 17 th Century ........................................................................................ 4 3 - Completion of the Parterre in the 18 th Century ........................................................................... 5 4 - The Steady Disappearance of the Garden .................................................................................. 7 II – SCIENTIFIC APPROACH ........................................................................................................... 8 1 - A Methodical and Scientific Investigation .................................................................................. 8 2 - Historical Research (2003–2014) .................................................................................................. 8 3 - Archaeological and Geophysical Surface Surveys (2013–2014) .................................................. 8 4 - Planned Archaeological Digs (2016) ............................................................................................ 9 III – COMPOSITION OF FRENCH FORMAL GARDENS ........................................................ -

The French Style

The French style In the reign of Louis XIV., the formal garden reached a height that could never be surpassed. This era combined an ingenious artist, an enthusiastic ruler with unlimited powers, technical skill unknown up until that time and a abundance of practical fellow-artists to make the individual arts and garden areas combine to be successful as a whole It followed that the art of gardens grew to its utmost height, and became a dominate style in the western world The northern garden style originated in France, and became the one shining example for Middle and Northern Europe. All eyes were fixed on the magic place Versailles; and to emulate this work of art was the aim of all ambitions. No imitator, however, could attain his object completely, because nowhere else did circumstances combine so favorably. The great importance of the style lay in its adaptability to the natural conditions of the North, and in the fact that it was easily taught and understood. Thus we have a remarkable spectacle: in spite of the fact that immediately after Louis’ death the picturesque style appeared—that enemy destined to strike a mortal blow at a fashion which was at least a thousand years old—for some decades later there came into being many specimens of the finest formal gardens, and the art flourished, especially in countries like Germany, Russia, and Sweden. France did not become mistress of Europe in garden art merely because of such of her examples as could be copied; of almost equal importance was the wide popularity of a book which first appeared anonymously in France in 1709 under the name of Théorie et Pratique du Jardinage.