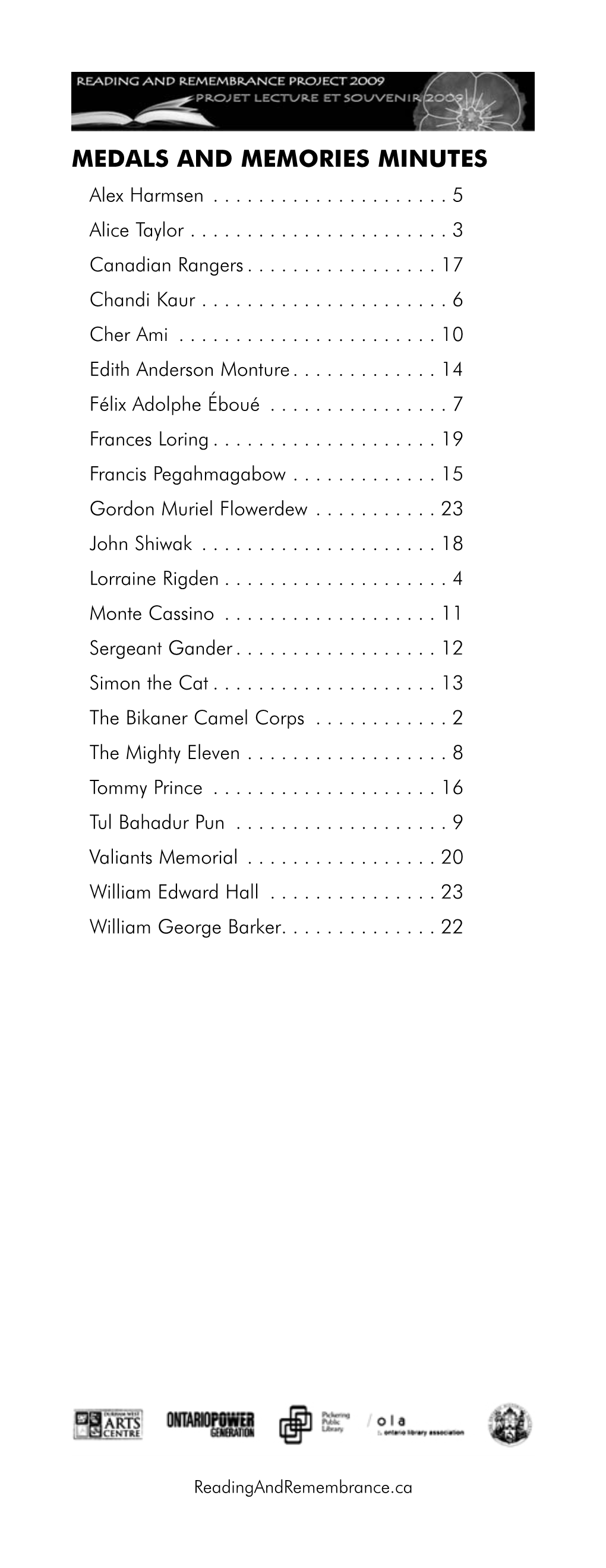

Minutes Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fom,990-PF Or Section 4947(A)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated As a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury Note

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Fom,990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2011 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number rlnmininn Fni inrlnfinn 13-Rn77762 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/sude B Telephone number (see instructions) 501 Martindale Street 400 ( 804 ) 771-4134 City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► Pittsburg h PA 15212 q G Check all that apply q Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q Address change q Name change check here and attach computation ► q H Check type of organization Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated q q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method q Cash ® Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here of year (from Part Il, col (c), q Other (specify) ..... ................... 0- El line 16) ► $ 36 273 623 Part / column (d) must be on cash basis ) (d) Disbursements Analysis of -

Member Motion City Council MM7.6

Member Motion City Council Notice of Motion MM7.6 ACTION Ward: All Accepting the Donation of the Royal Canadian Air Force Wing Commander Lieutenant-Colonel William G. Barker Memorial Statue - by Councillor Paul Ainslie, seconded by Mike Layton * Notice of this Motion has been given. * This Motion is subject to referral to the Economic and Community Development Committee. A two-thirds vote is required to waive referral. Recommendations Councillor Paul Ainslie, seconded by Mike Layton, recommends that: 1. City Council accept the donation of the William Barker Memorial Statue by Armando Barbon, subject to the conditions of the Public Art and Monuments Donations Policy and subject to a donation agreement with the Donor, and City Council request City staff to determine the location for the statue in a high-pedestrian-volume site within the former City of Toronto area. Summary Toronto has rich history. Commemorating significant contributors who had an impact the City's fabric is important. William George Barker, Victoria Cross recipient, born in 1894, first came to live in Toronto in 1919 following World War I with his best friend Billy Bishop. Mr. Barker would call the City of Toronto his home until his death in 1930. During his short life, William G. Barker VC had a substantial influence on the City with his numerous achievements including: created the first commercial airline (“Bishop Barker Airlines”) that flew out of Armour Heights and from Lake Ontario by what is aptly named Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport; requested the first landing rights at the City Island for a venture that flew passengers from Toronto to Muskoka during the summer months; with Billy Bishop, began what is now known as the Toronto International Air Show; was the first President of the newly christened Toronto Maple Leafs under new owner Conn Smythe, whom William G. -

Allies Closing Ring on Ruhr Reds Seize Hodges' Left Hook Flanks Ruhr Bocholt I 1St Army, British Danzig and 45 U-Boats Only 55 Mi

LIEGE EDITION Today Is THE mm Today Is D+298 Daily Mews paper of U.S. Armed Forces in the European Theater of Operations D+298 Vol. I—No. 71 Saturday, March 31, 1945 Allies Closing Ring on Ruhr Reds Seize Hodges' Left Hook Flanks Ruhr Bocholt I 1st Army, British Danzig and Only 55 Mi. Apart; 45 U-Boats Marshal Stalin last night announc- ed the capture of Danzig, with 10,000 9th's Armor Loose prisoners and 45 submarines, and the seizure of five Nazi strongpoints in Complete encirclement of the Ruhr appeared imminent last night a» a 31-mile breakthrough along the tanks of the First U.S. and Second British Armies were within 55 mile* north bank of the Danube east of Vienna. of alinkup northeast of the last great industrial region of the Beich. Berlin announced at the same time that German troops had given up their The Germans were rushing armor and self-propelled guns into the hold on the west bank section of Kustrin gap in a desperate effort to block the junction, but latest reports said the, on the Oder, 40 miles east of Berlin. Allied spearheads were still unchecked. Hitler's troops also yielded their last foothold east of the Oder at Lengenberg, Meanwhile, Ninth U.S. Army tanks broke out of their lower Rhine northwest of Kustrin. Evacuation of the bridgehead and drove east, but their farthest advances were screened by neighboring bridgehead of Zehden, 28 security silence. The exact location of the British tanks was not disclosed, miles northwest of Kustrin, was announc- but the First Army's Third Armd. -

List of Section 13F Securities

List of Section 13F Securities 1st Quarter FY 2004 Copyright (c) 2004 American Bankers Association. CUSIP Numbers and descriptions are used with permission by Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No redistribution without permission from Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau. Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the CUSIP Numbers and standard descriptions included herein and neither the American Bankers Association nor Standard & Poor's CUSIP Service Bureau shall be responsible for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of the use of such information. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission OFFICIAL LIST OF SECTION 13(f) SECURITIES USER INFORMATION SHEET General This list of “Section 13(f) securities” as defined by Rule 13f-1(c) [17 CFR 240.13f-1(c)] is made available to the public pursuant to Section13 (f) (3) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [15 USC 78m(f) (3)]. It is made available for use in the preparation of reports filed with the Securities and Exhange Commission pursuant to Rule 13f-1 [17 CFR 240.13f-1] under Section 13(f) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. An updated list is published on a quarterly basis. This list is current as of March 15, 2004, and may be relied on by institutional investment managers filing Form 13F reports for the calendar quarter ending March 31, 2004. Institutional investment managers should report holdings--number of shares and fair market value--as of the last day of the calendar quarter as required by Section 13(f)(1) and Rule 13f-1 thereunder. -

Sudan, Imperialism, and the Mahdi's Holy

bria_29_3:Layout 1 3/14/2014 6:41 PM Page 6 bria_29_3:Layout 1 3/14/2014 6:41 PM Page 7 the rebels. Enraged mobs rioted in the Believing these victories proved city and killed about 50 Europeans. that Allah had blessed the jihad, huge SUDAN, IMPERIALISM, The French withdrew their fleet, but numbers of fighters from Arab tribes the British opened fire on Alexandria swarmed to the Mahdi. They joined AND THE MAHDI’SHOLYWAR and leveled many buildings. Later in his cause of liberating Sudan and DURING THE AGE OF IMPERIALISM, EUROPEAN POWERS SCRAMBLED TO DIVIDE UP the year, Britain sent 25,000 troops to bringing Islam to the entire world. AFRICA. IN SUDAN, HOWEVER, A MUSLIM RELIGIOUS FIGURE KNOWN AS THE MAHDI Egypt and easily defeated the rebel The worried Egyptian khedive and LED A SUCCESSFUL JIHAD (HOLY WAR) THAT FOR A TIME DROVE OUT THE BRITISH Egyptian army. Britain then returned British government decided to send AND EGYPTIANS. the government to the khedive, who Charles Gordon, the former governor- In the late 1800s, many European Ali established Sudan’s colonial now was little more than a British general of Sudan, to Khartoum. His nations tried to stake out pieces of capital at Khartoum, where the White puppet. Thus began the British occu- mission was to organize the evacua- Africa to colonize. In what is known and Blue Nile rivers join to form the pation of Egypt. tion of all Egyptian soldiers and gov- as the “scramble for Africa,” coun- main Nile River, which flows north to While these dramatic events were ernment personnel from Sudan. -

Ward Churchill, the Law Stood Squarely on Its Head

81 Or. L. Rev. 663 Copyright (c) 2002 University of Oregon Oregon Law Review Fall, 2002 81 Or. L. Rev. 663 LENGTH: 12803 words SOCIAL JUSTICE MOVEMENTS AND LATCRIT COMMUNITY: The Law Stood Squarely on Its Head: U.S. Legal Doctrine, Indigenous Self-Determination and the Question of World Order WARD CHURCHILL* BIO: * Ward Churchill (Keetoowah Cherokee) is Chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies and Professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Colorado/Boulder. Among his numerous books are: Since Predator Came: Notes from the Struggle for American Indian Liberation (1995), A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present (1997) and, most recently, Perversions of Justice: Indigenous Peoples and Angloamerican Law (2002). SUMMARY: ... As anyone who has ever debated or negotiated with U.S. officials on matters concerning American Indian land rights can attest, the federal government's first position is invariably that its title to/authority over its territoriality was acquired incrementally, mostly through provisions of cession contained in some 400 treaties with Indians ratified by the Senate between 1778 and 1871. ... The necessity of getting along with powerful Indian [peoples], who outnumbered the European settlers for several decades, dictated that as a matter of prudence, the settlers buy lands that the Indians were willing to sell, rather than displace them by other methods. ... Under international law, discoverers could acquire land only through a voluntary alienation of title by native owners, with one exception - when they were compelled to wage a "Just War" against native people - by which those holding discovery rights might seize land and other property through military force. -

Riding Into 05 0

IN THIS ISSUE: Fighting from the saddle – horses, camels, and elephants VOL XI, ISSUE 5 WWW.ANCIENT-WARFARE.COM // KARWANSARAY PUBLISHERS KARWANSARAY // WWW.ANCIENT-WARFARE.COM JAN / FEB 2018 US/CN $11.99 €7,50 / CHF 7,50 RIDING INTO 05 0 07412 BATTLE Ancient mounted warfare 74470 0 THEME – ROMAN CAMEL UNITS // THE BATTLE OF THAPSUS // RUNNING WITH THE HORSES SPECIALS – LOOKING AT THE PYDNA MONUMENT // PILA TACTICS // WHO WERE THE VEXILLARII? TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE Publisher: Rolof van Hövell tot Westerflier Managing Director: Jasper Oorthuys Editor: Jasper Oorthuys Proofreader: Naomi Munts THEME: RIDiNG INTO BATTLE Design & Media: Christianne C. Beall Horse cavalry has long played a role in warfare. But other, Design © 2016 Karwansaray Publishers more exotic mounts were also used in the ancient world. Contributors: Duncan B. Campbell, Myke Cole, Murray Dahm, Jan Eschbach, Joseph Hall, Robert C.L. Holmes, Michael Livingston, Paul McDonnell- Staff, Lindsay Powell, Evan Schultheis, Tacticus 16 Riding into history 28 Final fight with elephants Illustrators: Seán Ó’Brógáín, Tomás Ó’Brógáín, Igor Historical introduction The Battle of Thapsus, 46 BC Dzis, Rocío Espin, Jose G. Moran, Johnny Shumate, Graham Sumner 18 Patrolling the desert 38 The Hamippoi Print: Grafi Advies Roman dromedary troops Running with the horses Editorial office 23 Bane of behemoths 43 Keeping the horses fit PO Box 4082, 7200 BB Zutphen, The Netherlands Phone: +31-575-776076 (EU), +1-740-994-0091 (US) Anti-elephant tactics Veterinaries of the Roman army E-mail: [email protected] Customer service: [email protected] Website: www.ancient-warfare.com SPECIAL FEATURES Contributions in the form of articles, letters, re- views, news and queries are welcomed. -

JULIA, ANNE, MARIE PONT Née Le 22 Avril 1975 À PARIS XVI

ENVT ANNEE 2003 THESE : 2003- TOU 3 DES ANIMAUX, DES GUERRES ET DES HOMMES De l’utilisation des animaux dans les guerres de l’antiquité à nos jours THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR VETERINAIRE DIPLOME D’ETAT Présentée et soutenue publiquement en 2003 Devant l’Université Paul-Sabatier de Toulouse Par JULIA, ANNE, MARIE PONT Née le 22 avril 1975 à PARIS XVI Directeur de thèse : M. le Professeur Michel FRANC JURY Liste des professeurs 2 A Monsieur le Professeur …. 3 Professeur de la faculté de Médecine de Toulouse Qui nous a fait l’honneur d’accepter la présidence de notre jury de thèse A Monsieur le Professeur Michel Franc Professeur à l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de Toulouse Qui a accepté de diriger cette thèse, pour la confiance et la patience qu’il a bien voulu m’accorder. Je vous témoigne toute ma gratitude et ma profonde reconnaissance. A Monsieur….. Professeur à l’Ecole Nationale vétérinaire de Toulouse Pour l’attention qu’il a bien voulu apporter à l’examen de ce travail 4 A mes parents, présents au jour le jour. Ce que je suis aujourd’hui je vous le dois. Vous m’avez épaulée dans chaque moment de ma vie, soutenue dans tous les tracas et les aléas de l’existence, poussée en avant pour tenter de donner le meilleur de moi-même. Si aujourd’hui je réalise mon rêve d’enfant, c’est en grande partie grâce à vous, à la ligne de conduite que vous m’avez montrée, autant dans ma vie personnelle que professionnelle. -

Report on San Miguel Island of the Channel Islands, California

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE rtr LIBRARY '"'' Denver, Colorado D-1 s~ IJ UNITED STATES . IL DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE I ' I I. i? ~~ REPORT ON 1 ·•*·;* SAN MIGUEL ISLAND ii' ' ·OF THE CHANNEL ISLANDS .. CALIFORNIA I. November 1, 1957 I " I ' I~ 1· Prepared By I Region Four, National Park Service Division of Recreation. Resource Planning I GPO 975965 I CONTENTS SUMMARY SECTION 1 ---~------------------------ CONCLUSIONS - ------------------------------- z ESTIMATED COSTS --------------------------- 3 REPORT -----------------------"-------------- 5 -I Authorization and Purpose __ .;, ______________ _ 5 Investigation Activities --------------------- 5 ,, 5 Population ---'-- ~------- - ------------------ Accessibility ----------------- ---- - - - ----- 6 Background Information -------------------- 7 I Major Characteristics --------------------- 7 Scenic Features --------------------- 7 Historic or prehistoric features -------- 8 I Geological features- - ------ --- ------- -- lZ .Biological features------------'-•------- lZ Interpretive possibilities-------------- 15 -, Other recreation possibilities -"'.-------- 16 NEED FOR CONSERVATION 16 ;' I BOUNDARIES AND ACREAGE 17 1 POSSIBLE DEVELOPMENT ---------------------- 17 PRACTICABILITY OF ADMINISTRATION, I OPERATION, PROTECTION AND PUBLIC USE--- 17 OTHER LAND RESOURCES OR USES -------------- 18 :.1 LAND OWNERSHIP OR STATUS------------------- 19 ·1 LOCAL ATTITUDE -----------------------•------ 19 PROBABLE AVAILABILITY----------------------- 19 'I PERSONS INTERESTED-------------------------- -

Conclusion (Volume

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Conclusion At the time of his death, Professor Lillich’s manuscript was lacking only a concluding statement of the contemporary law governing the forcible protection of nationals abroad. Although we were determined to present his work without substantive alteration, we did want this volume to be as comprehensive as possible. An editorial consensus emerged that we should append a chapter as a complementary snapshot of the law as it exists today. The following article, written by a co-editor of this volume and originally published in the Dickinson Law Review in the Spring of 2000, fit the bill. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of The Dickinson Law School of The Pennsylvania State University.† We hope that it is an appropriate punctuation mark for Professor Lillich’s research and analysis, and that it may serve as a point of departure for those scholars who will build on his impressive body of work Forcible Protection of Nationals Abroad Thomas C. Wingfield “It was only one life. What is one life in the affairs of a state?” —Benito Mussolini, after running down a child in his automobile (as reported by Gen. Smedley D. Butler in address, 1931)1 “This Government wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead.” —Theodore Roosevelt, committing the United States to the protection of Ion Perdicaris, kidnapped by Sherif Mulai Ahmed ibn-Muhammed er Raisuli (in State Department telegram, June 22nd, 1904)2 † Thomas C. Wingfield, Forcible Protection of Nationals Abroad, 104 DICK.L.REV. 493 (2000). Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner, The Dickinson School of Law of The Pennsylvania State University. -

Fourth Plenary Workshop of the Interpares 3, Project TEAM Canada

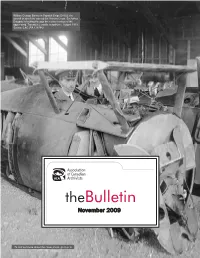

William George Barker in Sopwith Snipe E8102, the aircraft in which he earned the Victoria Cross. Sir Arthur Doughty is looking through the center section of the upper wing. Toronto’s Leaside aerodrome, August 1919. Source: LAC (PA 138786) Association of Canadian Archivists theBulletin NovemberJune 2008 2009 To find out more about the cover photo, go to p. 9 Association of Canadian Archivists Submissions, suggestions and any questions should be addressed to: I.S.S.N. 0709-4604 Editor: Loryl MacDonald, [email protected] November 2009, Vol. 33 No. 4 Submission deadlines for the Bulletins scheduled for P.O. Box 2596, Station D, the remainder of 2009: Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W6 Tel: (613) 234-6977 Issue Submission deadline Fax: (613) 234-8500 Fall issue Sept 3 Email: [email protected] Winter issue Nov 9 The views expressed in the Bulletin are not necessarily those of the Penny Warne, Layout and Design Board of Directors of the Association of Canadian Archivists. [email protected] The Bulletin is usually published quarterly by the Association of Canadian Archivists. ACA Board Members President: Paul Banfield, [email protected] ACA Secretariat Vice President: Rod Carter, [email protected] Administrative Coordinator: Judy Laird Secretary-Treasurer: Michele Dale, [email protected] Executive Director: Duncan Grant Director at Large: Heather Pitcher, [email protected] Table of Contents Letter From th e Editor ..................................................3 Wish You Were Here…. Here’s how some of Historical Perspectives -

Information Resources on Old World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1962-2003"

NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL LIBRARY ARCHIVED FILE Archived files are provided for reference purposes only. This file was current when produced, but is no longer maintained and may now be outdated. Content may not appear in full or in its original format. All links external to the document have been deactivated. For additional information, see http://pubs.nal.usda.gov. "Information resources on old world camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1962-2003" NOTE: Information Resources on Old World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian, 1941-2004 may be viewed as one document below or by individual sections at camels2.htm Information Resources on Old United States Department of Agriculture World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1941-2004 Agricultural Research Service November 2001 (Updated December 2004) National Agricultural AWIC Resource Series No. 13 Library Compiled by: Jean Larson Judith Ho Animal Welfare Information Animal Welfare Information Center Center USDA, ARS, NAL 10301 Baltimore Ave. Beltsville, MD 20705 Contact us : http://www.nal.usda.gov/awic/contact.php Policies and Links Table of Contents Introduction About this Document Bibliography World Wide Web Resources Information Resources on Old World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1941-2004 Introduction The Camelidae family is a comparatively small family of mammalian animals. There are two members of Old World camels living in Africa and Asia--the Arabian and the Bactrian. There are four members of the New World camels of camels.htm[12/10/2014 1:37:48 PM] "Information resources on old world camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1962-2003" South America--llamas, vicunas, alpacas and guanacos. They are all very well adapted to their respective environments.