(INCS) Vol. XVII (2011), No. 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LABOR and the SOVIET SYSTEM, by Romuald Szumski, Is a Factual Story About the Destruction of Democratic Trade Unions Under Russian Bolshevism

c NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR A FREE EUROPE, INC. 350 Fifth Avenue, New York 1, N. Y. Telephone: BRyant 9-2100 LABOR AND THE SOVIET SYSTEM, by Romuald Szumski, is a factual story about the destruction of democratic trade unions under Russian Bolshevism. The author clearly shows that real trade unions do not exist in Russia or its satellite countries. He describes Soviet slavery and the extension of this most barbaric system of Russian imperialism into Eastern Europe. This hard-hitting account is the answer to those who think free workers have nothing to fear from the Kremlin's "dictatorship of the proletariat*1. I strongly urge you to read LABOR AND THE SOVIET SYSTEM and see the deceptive and fraudulent tactics and devices of Russian communism exposed. I ask you to join us in the relentless battle to restore and preserve freedom and peace. Please write me if you would like further details of our Committee. C, D. Jackson April, 19^1 ~; President Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis By Komuald Szumski LABOE and the Soviet System National Committee for a Free Eurbpe, Inc. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis o ONLY A WORLD BUILT ON THE IDEALS OF FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY CAN LIVE IN PEACE NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR A FREE EUROPE, INC. 301 Empire State Building 350 Fifth Avenue, New York 1, N. Y. MEMBERS C. L. Adcock William Green Raymond Pace Alexander Joseph C. Grew Frank Altschul Charles R. Hook Laird Bell Palmer Hoyt A. -

The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness--A Soviet Spymaster Ebook

SPECIAL TASKS: THE MEMOIRS OF AN UNWANTED WITNESS--A SOVIET SPYMASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anatoli Sudoplatov, Pavel Sudoplatov, Leona P Schecter, Jerrold L Schecter | 576 pages | 01 Jun 1995 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316821155 | English | Boston, MA, United States Lord of the spies: The 4 most impressive operations by Stalin’s chief spymaster - Russia Beyond Robert Oppenheimer and Leo Szilard, all of whom are dead and were eminent scientists. Both Dr. Bohr and Dr. Fermi won the Nobel Prize for basic discoveries in physics, the former in and the latter in Szilard, a Hungarian, was the chief physicist for the Manhattan Project, the nation's atom bomb project. Oppenheimer was the scientific director of the Los Alamos laboratory in the mountains of New Mexico during the war. The scientists there built the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The book, which offered little evidence other than Mr. Sudoplatov's recollections to back up its accusations, was excerpted in Time on April 25, , and ignited a global controversy as outraged scientists and historians rushed to defend the dead luminaries. Aspin had asked for the review on March Director, Louis J. Given Moscow's remarkable successes in placing Fuchs and Donald Maclean as atom spies, it would be brave to declare categorically that none of these four - Oppenheimer, Fermi, Szilard or Bohr - could possibly have been agents, or at least helpful sympathisers. But to assert, without supporting evidence, that they all were, is to smear them. These are four of the inspirational figures of modern physics: they deserve better. Independent Premium Comments can be posted by members of our membership scheme, Independent Premium. -

PMA Polonica Catalog

PMA Polonica Catalog PLACE OF AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER DATE DESCRIPTION CALL NR PUBLICATION Concerns the Soviet-Polish War of Eighteenth Decisive Battle Abernon, De London Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd. 1931 1920, also called the Miracle on the PE.PB-ab of the World-Warsaw 1920 Vistula. Illus., index, maps. Ackermann, And We Are Civilized New York Covici Friede Publ. 1936 Poland in World War I. PE.PB-ac Wolfgang Form letter to Polish-Americans asking for their help in book on Appeal: "To Polish Adamic, Louis New Jersey 1939 immigration author is planning to PE.PP-ad Americans" write. (Filed with PP-ad-1, another work by this author). Questionnaire regarding book Plymouth Rock and Ellis author is planning to write. (Filed Adamic, Louis New Jersey 1939 PE.PP-ad-1 Island with PE.PP-ad, another work by this author). A factual report affecting the lives Adamowski, and security of every citizen of the It Did Happen Here. Chicago unknown 1942 PA.A-ad Benjamin S. U.S. of America. United States in World War II New York Biography of Jan Kostanecki, PE.PC-kost- Adams , Dorothy We Stood Alone Longmans, Green & Co. 1944 Toronto diplomat and economist. ad Addinsell, Piano solo. Arranged from the Warsaw Concerto New York Chappell & Co. Inc. 1942 PE.PG-ad Richard original score by Henry Geehl. Great moments of Kosciuszko's life Ajdukiewicz, Kosciuszko--Hero of Two New York Cosmopolitan Art Company 1945 immortalized in 8 famous paintings PE.PG-aj Zygumunt Worlds by the celebrated Polish artist. Z roznymi ludzmi o roznych polsko- Ciekawe Gawedy Macieja amerykanskich sprawach. -

1000 Ans De Vie Juive En Pologne Une Chronologie. Traduit Par Natalia Krasicka

de vie juiveans en Pologne 1000 ans de vie juive en Pologne une chronologie. Traduit par Natalia Krasicka Version française réalisé par le en coopération avec la Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture et le Consul honoraire de la République de Pologne, région de la Baie de San Francisco Le projet est cofi nancé par le Ministère des Affaires Étrangères de la République de Pologne. Les opinions exprimées dans la présente publication n’engagent que leur auteur et ne refl ètent pas le point de vue offi ciel du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères de la République de Pologne. La présente version linguistique est réalisée dans le cadre du projet « Histoire commune, nouveaux chapitres ». En hébreu, Pologne se dit Polin (ce qui signifi e « repose-toi ici » ou « habite ici »). En effet, au cours de l’histoire, les Juifs ont la plupart du temps trouvé en Pologne un lieu où se reposer, habiter et se sentir chez eux. L’histoire des Juifs polonais est certes lourde de traumatismes mais elle est aussi porteuse de créativité et de réalisations cultu- relles extraordinaires. C’est une histoire faite de récits interdépendants. Cette chronologie en fournit les dates clés, elle présente les personnalités et les tendances qui illustrent la richesse et la complexité de ces mille ans de vie des Juifs de Pologne. I. POLIN: ÉTABLISSEMENT DES JUIFS EN POLOGNE, 965-1569 965-966 Un commerçant juif d’Espagne, Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, voyage en Pologne et rédige les premières descriptions du pays. Aux Xe et XIe siècles, des marchands et des artisans juifs s’éta- blissent en Pologne. -

Communisttakeove545503unit Bw.Pdf

rfr Bi cJVp *9335.4A?70 Given By Charles J. Kersten 4&~ SPECIAL REPORTS OF U,5 ( —* SSL3CT ca.lIITTBB ON Caa:UNI ST AGGRESSI ON TAKEOVER AM) OCCUPATION COMMUNIST - mi mm*iii miBiKi if — r7 </o pts • 1-16 UNITED STATES GOVERNT-ENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 195U-1955 * • o> / CONTENTS No. 26814., pts. 1-16. Special reports of Select Com- mittee on Communist Aggression. Pfc. 1. Communist takeover and occupation of Latvia. 2 • Communist takeover and occupation of Albania. 3» Communist takeover and occupation of Poland. U» Appendix to Committee report on communist takeover and occupation of Poland. 5« Treatment of Jews under communism. 6. Communist takeover and occupation of Estonia. 7. Communist takeover and occupation of Ukraine. 8. Communist takeover and occupation of Armenia. 9» Communist takeover and occupation of Georgia* 10. Communist takeover and occupation of Bulgaria. 11. Communist takeover and occupation of Byelorussia. 12. Communist takeover and occupation of Hungary. 13* Communist takeover and occupation of Lithuania. lU. Communist takeover and occupation of Czechoslovakia. „ 15* Communist takeover and occupation of Rumania. 16. Summary report of Select Committee on Communist Aggression. / Union Calendar No. C29 j ~~d Congress, 2d Session - House Report No. 2684, Part 3 COMMUNIST TAKEOVER AND OCCUPATION OF POLAND U.S. SPECIAL REPORT NO. 1 OP THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON COMMUNIST AGGRESSION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES EIGHTY-THIRD CONGRESS SECOND SESSION UNDER AUTHORITY OP H. Res. 346 and H. Res. 438 December 31, 1954.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 65929 WASHINGTON : 1955 ^-~~ 7 \, H« HOUSE SELECT COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE COMMUNIST AGGRESSION AND THE FORCED INCORPORATION OF THE BALTIC STATES INTO THE U. -

Raoul Wallenberg: Report of the Swedish-Russian Working Group

Raoul Wallenberg Report of the Swedish-Russian Working Group STOCKHOLM 2000 Additional copies of this report can be ordered from: Fritzes kundservice 106 47 Stockholm Fax: 08-690 9191 Tel: 08-690 9190 Internet: www.fritzes.se E-mail: [email protected] Ministry for Foreign Affairs Department for Central and Eastern Europe SE-103 39 Stockholm Tel: 08-405 10 00 Fax: 08-723 11 76 _______________ Editorial group: Ingrid Palmklint, Daniel Larsson Cover design: Ingrid Palmklint Cover photo: Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest, November 1944, Raoul Wallenbergföreningen Printed by: Elanders Gotab AB, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN: ISBN: 91-7496-230-2 2 Contents Preface ..........................................7 I Introduction ...................................9 II Planning and implementation ..................12 Examining the records.............................. 16 Interviews......................................... 22 III Political background - The USSR 1944-1957 ...24 IV Soviet Security Organs 1945-1947 .............28 V Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest .................32 Background to the assignment....................... 32 Operations begin................................... 34 Protective power assignment........................ 37 Did Raoul Wallenberg visit Stockholm in late autumn 1944?.............................................. 38 VI American papers on Raoul Wallenberg - was he an undercover agent for OSS? .........40 Conclusions........................................ 44 VII Circumstances surrounding Raoul Wallenberg’s detention and arrest in Budapest -

In Soviet Poland and Lithuania

IN SOVIET POLAND AND LITHUANIA By DAVID GRODNER IGID censorship and the absence of accredited news correspond- ents have made it impossible for American readers to learn R" what is really happening to Jews in Soviet Poland and Lith- uania. The impression that Polish refugees have found a friendly home in these areas is fostered largely by Communist propaganda, which has publicized the letters of those elated by their escape from Nazi Poland or those who had the good fortune to make a fair ad- justment under the new conditions. Having spent at least six months in Soviet Poland and more than that time in Lithuania, including the period of its occupation, I feel it my duty to tell what I have seen happen to the religious, communal and cultural life of Jews under their new Soviet masters. In particular, more ought to be known about the fate of at least one hundred thousand Polish Jewish refugees who sought aliaven from the Nazi invaders only to be driven mercilessly to the frozen tundras of Siberia. Newspapers in the United States have exaggerated the number of Jews in Soviet Poland. Altogether, there are about 1,200,000 Jews in Western Ukraine (former Galicia) and Western Byelorosya (White Russia). In addition, approximately 500,000 Jews fled there from Nazi Poland. About 60% of these refugees, it must be noted, arrived before the Red Army entered the country. On the night of September 6, 1939, the propaganda chief of the Polish Army announced over the radio that Warsaw was to be evacuated and ordered all inhabitants of military age to leave the city.* (Later, it was rumored that this official was a German spy carrying out Nazi orders.) About 200,000 persons left Warsaw that night and headed for the Bug River, where the Polish Army was planning to make a last stand. -

Jewish Labor Bund's

THE STARS BEAR WITNESS: THE JEWISH LABOR BUND 1897-2017 112020 cubs בונד ∞≥± — A 120TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF THE FOUNDING OF THE JEWISH LABOR BUND October 22, 2017 YIVO Institute for Jewish Research at the Center for Jewish History Sponsors YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Jonathan Brent, Executive Director Workmen’s Circle, Ann Toback, Executive Director Media Sponsor Jewish Currents Executive Committee Irena Klepisz, Moishe Rosenfeld, Alex Weiser Ad Hoc Committee Rochelle Diogenes, Adi Diner, Francine Dunkel, Mimi Erlich Nelly Furman, Abe Goldwasser, Ettie Goldwasser, Deborah Grace Rosenstein Leo Greenbaum, Jack Jacobs, Rita Meed, Zalmen Mlotek Elliot Palevsky, Irene Kronhill Pletka, Fay Rosenfeld Gabriel Ross, Daniel Soyer, Vivian Kahan Weston Editors Irena Klepisz and Daniel Soyer Typography and Book Design Yankl Salant with invaluable sources and assistance from Cara Beckenstein, Hakan Blomqvist, Hinde Ena Burstin, Mimi Erlich, Gwen Fogel Nelly Furman, Bernard Flam, Jerry Glickson, Abe Goldwasser Ettie Goldwasser, Leo Greenbaum, Avi Hoffman, Jack Jacobs, Magdelana Micinski Ruth Mlotek, Freydi Mrocki, Eugene Orenstein, Eddy Portnoy, Moishe Rosenfeld George Rothe, Paula Sawicka, David Slucki, Alex Weiser, Vivian Kahan Weston Marvin Zuckerman, Michael Zylberman, Reyzl Zylberman and the following YIVO publications: The Story of the Jewish Labor Bund 1897-1997: A Centennial Exhibition Here and Now: The Vision of the Jewish Labor Bund in Interwar Poland Program Editor Finance Committee Nelly Furman Adi Diner and Abe Goldwasser -

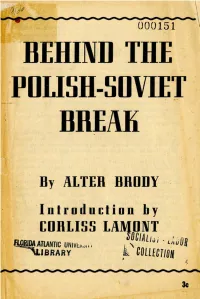

Behind the Polish-Soviet Break

,BEHIND THE POLISH-SOVIET BREAK By ALTER BRODY -I n I rod II eli 0 n h y [OBLISS LAl\fo~/~! " ~JlANTIG UNIV""".. , i '\ LI",. <HoUR - ISRARY ~ . COLLECTION , ~ • 3c l Introduction OVIETR USSIA'S severan ce of relations with the Polish S Government-in-Exile, over the Nazi-inspired charge that the Russians murdered 10,000 Polish army officers, sh ows clearly the danger to the United N ations of the splitting tac tics engineered by Hitler and definitely helped along by the general campaign of anti-Soviet propaganda carried on during recent months in Britain and America. According to the London Bureau of the N ew York Herald Tribune, " It is a safe assumption that the Poles would not have taken so tough an a tt itu de toward the Soviet Government if it had not been for the widespread support Americans have been giving them in the cases of H enry Ehrlich and Victor Alter." It is significant, too, to note, as Professor Lange of the Uni versity of Chicago has pointed out, that the American Friends of Poland, an anti-Soviet organization under the wing of the Polish Embassy, counts among its members some of America's foremost isolationists and America Firsters such as Colonel Langhom, its chairman; General Wood, Mr. John Cudahy, Mr. Robert Hall McCormick and Miss Lucy Martin. These individuals have all been leading advocates of a negotiated peace with Hitler at the expense of Soviet Russia. Mr. Walter Lippmann well sums up the matter in his column "T od ay' and Tomorrow" when h e states that the net effect of American public opinion has . -

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS of SOVIET Terroi\

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I --' . ' J ,j HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF SOVIET TERROi\ .. HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBOOMMITTEE ON SECURITY AND TERRORISM OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED ST.A.g;ES;~'SEN ATE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF SOVIET TERRORISM JUNE 11 AND 1~, 1981 Serial No.. J-97-40 rinted for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary . ~.. ~. ~ A\!?IJ.ISIJl1 ~O b'. ~~~g "1?'r.<f~~ ~l~&V U.R. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1981 U.S. Department ':.~ Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permissic;m to reproduce this '*ll'yr/gJorbJ material has been CONTENTS .::lrante~i,. • . l-'ubllC Domain UTIltea~tates Senate OPENING STATEMENTS Page to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Denton, Chairman Jeremiah ......................................................................................... 1, 29 Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the 00j5) I i~ owner. CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WITNESSES JUNE 11, 1981 COMMI'ITEE ON THE JUDICIARY Billington, James H., director, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars ......................................................................................................................... 4 STROM THU'lMOND;1South Carolina, Chairman Biography .................................................................................................................. 27 CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., Maryland JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL LAXALT Nevada EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JUNE 12, 1981 ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia. Possony, Stefan T., senior fellow (emeritus), Hoover Institution, Stanford Uni- ROBERT DOLE Kansas HOWARD M. -

Democracy's Champion: Albert Shanker and The

DEMOCRACY’S CHAMPION ALBERT SHANKER and the International Impact of the American Federation of Teachers By Eric Chenoweth BOARD OF DIRECTORS Paul E. Almeida Anthony Bryk Barbara Byrd-Bennett Landon Butler David K. Cohen Thomas R. Donahue Han Dongfang Bob Edwards Carl Gershman The Albert Shanker Institute is a nonprofit organization established in 1998 to honor the life and legacy of the late president of the Milton Goldberg American Federation of Teachers. The organization’s by-laws Ernest G. Green commit it to four fundamental principles—vibrant democracy, Linda Darling Hammond quality public education, a voice for working people in decisions E. D. Hirsch, Jr. affecting their jobs and their lives, and free and open debate about Sol Hurwitz all of these issues. John Jackson Clifford B. Janey The institute brings together influential leaders and thinkers from Lorretta Johnson business, labor, government, and education from across the political Susan Moore Johnson spectrum. It sponsors research, promotes discussions, and seeks new Ted Kirsch and workable approaches to the issues that will shape the future of Francine Lawrence democracy, education, and unionism. Many of these conversations Stanley S. Litow are off-the-record, encouraging lively, honest debate and new Michael Maccoby understandings. Herb Magidson Harold Meyerson These efforts are directed by and accountable to a diverse and Mary Cathryn Ricker distinguished board of directors representing the richness of Al Richard Riley Shanker’s commitments and concerns. William Schmidt Randi Weingarten ____________________________________________ Deborah L. Wince-Smith This document was written for the Albert Shanker Institute and does not necessarily represent the views of the institute or the members of its Board EMERITUS BOARD of Directors. -

The New------NTERNATIONAL -----....1

The New--------- NTERNATIONAL -----....1 . Mortll • 1943 1.... ----- NOTES OF THE MONTH · War Labor Board Ehrlich and Alter THE ROAD TO SOCIALISM Political Resolution of the Workers Party National and Colonial Problems By Max S#Jac#Jfman Whither Zionism? Whither Jewry?--II By Karl Minfer Archive. • Book Revi.lN• • Correspondence SINGLE COpy 20c ONE YEAR $1.50 Boost Our Press! Two hundred and fifty new subscribers for The NEW THE NEW INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL, one thousand new subcribers for Labor Ac A Monthly Or.an of ••volutlonary Marxl... tion, by June 151 The readers and friends of both papers are mobilizing for a joint drive to raise the banner of socialist Vol. IX No.3, Whole No. 73 thougbt and socialJist action higher than ever before, in the Published monthly by the New International Publishing Co., very face of a difficult world situation and the rise of reaction. 114 West 14th Street, New York, N. Y. Telephone: CHelsea They are backed by the enthusiastic approval of the hundred 2-9681. Subscription rates: $1.50 per year; bundles, 14c for five copies and up. Canada and foreign: $1.75 per year; bundles, 16c or more delegates and visitors to the recent conference of for five and up. Entered as second-class matter July 10, 1940, at Workers Party activists. the post office at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 5,1879. The magnificent progress made by Labor Action during Editor: ALBERT GATES the past year gives us good reason to believe that LA will hold up its end of the drive.