Preserving Rockefeller Center Dorothy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoning ORDINANCE USER's MANUAL

CITY OF PROVIDENCEPROVIDENCE ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL PRODUCED BY CAMIROS ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL WHAT IS ZONING? The Zoning Ordinance provides a set of land use and development regulations, organized by zoning district. The Zoning Map identifies the location of the zoning districts, thereby specifying the land use and develop- ment requirements affecting each parcel of land within the City. HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL This User’s Manual is intended to provide a brief overview of the organization of the Providence Zoning Ordinance, the general purpose of the various Articles of the ordinance, and summaries of some of the key ordinance sections -- including zoning districts, uses, parking standards, site development standards, and administration. This manual is for informational purposes only. It should be used as a reference only, and not to determine official zoning regulations or for legal purposes. Please refer to the full Zoning Ordinance and Zoning Map for further information. user'’S MANUAL CONTENTS 1 ORDINANCE ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 2 ZONING DISTRICTS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 USES............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION N 980314 ZRM Subway

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION July 20, 1998/Calendar No. 3 N 980314 ZRM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the Department of City Planning, pursuant to Section 201 of the New York City Charter, to amend various sections of the Zoning Resolution of the City of New York relating to the establishment of a Special Lower Manhattan District (Article IX, Chapter 1), the elimination of the Special Greenwich Street Development District (Article VIII, Chapter 6), the elimination of the Special South Street Seaport District (Article VIII, Chapter 8), the elimination of the Special Manhattan Landing Development District (Article IX, Chapter 8), and other related sections concerning the reorganization and relocation of certain provisions relating to pedestrian circulation and subway stair relocation requirements and subway improvements. The application for the amendment of the Zoning Resolution was filed by the Department of City Planning on February 4, 1998. The proposed zoning text amendment and a related zoning map amendment would create the Special Lower Manhattan District (LMD), a new special zoning district in the area bounded by the West Street, Broadway, Murray Street, Chambers Street, Centre Street, the centerline of the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River and the Battery Park waterfront. In conjunction with the proposed action, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development is proposing to amend the Brooklyn Bridge Southeast Urban Renewal Plan (located in the existing Special Manhattan Landing District) to reflect the proposed zoning text and map amendments. The proposed zoning text amendment controls would simplify and consolidate regulations into one comprehensive set of controls for Lower Manhattan. -

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Empire State Building Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Advanced reservations are required. You will not be able to enter the Observatory without a timed reservation. Please visit the Empire State Building's website to book a date and time. You will need to have your pass number to hand when making your reservation. Getting in: please arrive with both your Reservation Confirmation and your pass. To gain access to the building, you will be asked to present your Empire State Building reservation confirmation. Your reservation confirmation is not your admission ticket. To gain entry to the Observatory after entering the building, you will need to present your pass for scanning. Please note: In light of COVID-19, we recommend you read the Empire State Building's safety guidelines ahead of your visit. Good to knows: Free high-speed Wi-Fi Eight in-building dining options Signage available in nine languages - English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Hours of Operation From August: Daily - 11AM-11PM Closings & Holidays Open 365 days a year. Getting There Address 20 West 34th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenue) New York, NY 10118 US Closest Subway Stop 6 train to 33rd Street; R, N, Q, B, D, M, F trains to 34th Street/Herald Square; 1, 2, or 3 trains to 34th Street/Penn Station. The Empire State Building is walking distance from Penn Station, Herald Square, Grand Central Station, and Times Square, less than one block from 34th St subway stop. Top of the Rock Observatory Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Getting In: Use the Rockefeller Plaza entrance on 50th Street (between 5th and 6th Avenues). -

City Record Edition

2597 VOLUME CXLVII NUMBER 116 TUESDAY, JUNE 16, 2020 Price: $4.00 Citywide Administrative Services � � � � � � � 2600 Office of Citywide Procurement � � � � � � � � 2600 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Comptroller � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2600 BILL DE BLASIO Mayor Health and Mental Hygiene � � � � � � � � � � � � 2601 PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Homeless Services � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2601 LISETTE CAMILO Borough President - Manhattan � � � � � � � � 2597 Housing Preservation & Development � � � 2601 Commissioner, Department of Citywide Board of Education Retirement System � � 2597 Administrative Services Human Resources Administration � � � � � � � 2601 Employees’ Retirement System � � � � � � � � � 2597 Parks and Recreation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2601 JANAE C. FERREIRA New York City Fire Pension Fund � � � � � � � 2598 Capital Projects � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2602 Editor, The City Record Housing Authority � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2598 Contracts � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2602 Office of Labor Relations � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2598 Published Monday through Friday except legal Police � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2602 holidays by the New York City Department of Landmarks Preservation Commission � � � 2598 Contract Administration � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2602 Citywide Administrative Services under Authority of Section 1066 of the New York City Charter� PROPERTY DISPOSITION Probation � -

EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers

TM EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers, Top of the RockTM at Rockefeller Center is an exciting destination for New York City students. Located on the 67th, 69th, and 70th floors of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the Top of the Rock Observation Deck reopened to the public in November 2005 after being closed for nearly 20 years. It provides a unique educational opportunity in the heart of New York City. To support the vital work of teachers and to encourage inquiry and exploration among students, Tishman Speyer is proud to present Top of the Rock Education Materials. In the Teacher Guide, you will find discussion questions, a suggested reading list, and detailed plans to help you make the most of your visit. The Student Activities section includes trip sheets and student sheets with activities that will enhance your students’ learning experiences at the Observation Deck. These materials are correlated to local, state, and national curriculum standards in Grades 3 through 8, but can be adapted to suit the needs of younger and older students with various aptitudes. We hope that you find these education materials to be useful resources as you explore one of the most dazzling places in all of New York City. Enjoy the trip! Sincerely, General Manager Top of the Rock Observation Deck 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York NY 101 12 T: 212 698-2000 877 NYC-ROCK ( 877 692-7625) F: 212 332-6550 www.topoftherocknyc.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Guide Before Your Visit . Page 1 During Your Visit . Page 2 After Your Visit . Page 6 Suggested Reading List . -

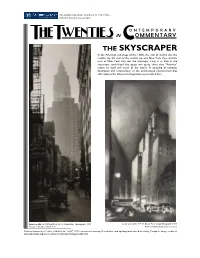

The Skyscraper of the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y IN OMMENTARY HE WENTIES T T C * THE SKYSCRAPER In the American self-image of the 1920s, the icon of modern was the modern city, the icon of the modern city was New York City, and the icon of New York City was the skyscraper. Love it or hate it, the skyscraper symbolized the go-go and up-up drive that “America” meant to itself and much of the world. A sampling of twenties illustration and commentary on the architectural phenomenon that still captures the American imagination is presented here. Berenice Abbott, Cliff and Ferry Street, Manhattan, photograph, 1935 Louis Lozowick, 57th St. [New York City], lithograph, 1929 Museum of the City of New York Renwick Gallery/Smithsonian Institution * ® National Humanities Center, AMERICA IN CLASS , 2012: americainclass.org/. Punctuation and spelling modernized for clarity. Complete image credits at americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/imagecredits.htm. R. L. Duffus Robert L. Duffus was a novelist, literary critic, and essayist with New York newspapers. “The Vertical City” The New Republic One of the intangible satisfactions which a New Yorker receives as a reward July 3, 1929 for living in a most uncomfortable city arises from the monumental character of his artificial scenery. Skyscrapers are undoubtedly popular with the man of the street. He watches them with tender, if somewhat fearsome, interest from the moment the hole is dug until the last Gothic waterspout is put in place. Perhaps the nearest a New Yorker ever comes to civic pride is when he contemplates the skyline and realizes that there is and has been nothing to match it in the world. -

Table of Contents

CITYFEBRUARY 2013 center forLAND new york city law VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1 Table of Contents CITYLAND Top ten stories of 2012 . 1 CITY COUNCIL East Village/LES HD approved . 3 CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CPC’s 75th anniversary . 4 Durst W . 57th street project . 5 Queens rezoning faces opposition . .6 LANDMARKSFPO Rainbow Room renovation . 7 Gage & Tollner change denied . 9 Bed-Stuy HD proposed . 10 SI Harrison Street HD heard . 11 Plans for SoHo vacant lot . 12 Special permits for legitimate physical culture or health establishments are debated in CityLand’s guest commentary by Howard Goldman and Eugene Travers. See page 8 . Credit: SXC . HISTORIC DISTRICTS COUNCIL CITYLAND public school is built on site. HDC’s 2013 Six to Celebrate . 13 2. Landmarking of Brincker- hoff Cemetery Proceeds to Coun- COURT DECISIONS Top Ten Stories Union Square restaurant halted . 14. cil Vote Despite Owner’s Opposi- New York City tion – Owner of the vacant former BOARD OF STANDARDS & APPEALS Top Ten Stories of 2012 cemetery site claimed she pur- Harlem mixed-use OK’d . 15 chased the lot to build a home for Welcome to CityLand’s first annual herself, not knowing of the prop- top ten stories of the year! We’ve se- CITYLAND COMMENTARY erty’s history, and was not compe- lected the most popular and inter- Ross Sandler . .2 tently represented throughout the esting stories in NYC land use news landmarking process. from our very first year as an online- GUEST COMMENTARY 3. City Council Rejects Sale only publication. We’ve been re- Howard Goldman and of City Property in Hopes for an Eugene Travers . -

Wurlington Press Order Form Date

Wurlington Press Order Form www.Wurlington-Bros.com Date Build Your Own Chicago postcards Build Your Own New York postcards Posters & Books Quantity @ Quantity @ Quantity @ $ Chicago’s Tallest Bldgs Poster 19" x 28" 20.00 $ $ $ Water Tower Postcard AR-CHI-1 2.00 Flatiron Building AR-NYC-1 2.00 Louis Sullivan Doors Poster 18” x 24” 20.00 $ $ $ Chicago Tribune Tower AR-CHI-2 2.00 Empire State Building AR-NYC-2 2.00 Auditorium Bldg Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ $ $ AR-NYC-3 3.5” x 5.5” Wrigley Building AR-CHI-3 2.00 Citicorp Center 2.00 John Hancock Memo Book 4.95 $ $ $ AT&T Building AR-NYC-4 2.00 Pritzker Pavilion Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 Sears Tower AR-CHI-4 2.00 $ $ Rookery Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ Chrysler Building AR-NYC-5 2.00 John Hancock Center AR-CHI-5 2.00 $ $ American Landmarks Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 $ Lever House AR-NYC-6 2.00 AR-CHI-6 Reliance Building 2.00 $ $ U.S. Capitol Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 AR-NYC-7 $ Seagram Building 2.00 Bahai Temple AR-CHI-7 2.00 $ $ Santa’s Workshop Cut & Asssemble Book 12.95 Woolworth Building AR-NYC-8 2.00 $ Marina City AR-CHI-9 2.00 Haunted House Cut & Asssemble Book $12.95 $ Lipstick Building AR-NYC-9 2.00 $ $ 860 Lake Shore Dr Apts AR-CHI-10 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Book 30.00 $ Hearst Tower AR-NYC-10 2.00 $ $ Lake Point Tower AR-CHI-11 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Zines (per issue) 2.75 $ AR-NYC-11 UN Headquarters 2.00 $ $ Flood and Flotsam Book 16.00 Crown Hall AR-CHI-12 2.00 $ 1 World Trade Center AR-NYC-12 2.00 $ AR-CHI-13 35 E. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

Off* for Visitors

Welcome to The best brands, the biggest selection, plus 1O% off* for visitors. Stop by Macy’s Herald Square and ask for your Macy’s Visitor Savings Pass*, good for 10% off* thousands of items throughout the store! Plus, we now ship to over 100 countries around the world, so you can enjoy international shipping online. For details, log on to macys.com/international Macy’s Herald Square Visitor Center, Lower Level (212) 494-3827 *Restrictions apply. Valid I.D. required. Details in store. NYC Official Visitor Guide A Letter from the Mayor Dear Friends: As temperatures dip, autumn turns the City’s abundant foliage to brilliant colors, providing a beautiful backdrop to the five boroughs. Neighborhoods like Fort Greene in Brooklyn, Snug Harbor on Staten Island, Long Island City in Queens and Arthur Avenue in the Bronx are rich in the cultural diversity for which the City is famous. Enjoy strolling through these communities as well as among the more than 700 acres of new parkland added in the past decade. Fall also means it is time for favorite holidays. Every October, NYC streets come alive with ghosts, goblins and revelry along Sixth Avenue during Manhattan’s Village Halloween Parade. The pomp and pageantry of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in November make for a high-energy holiday spectacle. And in early December, Rockefeller Center’s signature tree lights up and beckons to the area’s shoppers and ice-skaters. The season also offers plenty of relaxing options for anyone seeking a break from the holiday hustle and bustle. -

Rockefeller Center Complex Master Plan and Exterior Rehabilitations New York, New York

Rockefeller Center Complex Master Plan and Exterior Rehabilitations New York, New York Developed for the purpose of planning maintenance and capital improvement projects, Hoffmann National Trust for Architects’ Exterior Rehabilitation Master Plan for Rockefeller Center encompassed the nineteen Historic Preservation buildings of John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s 22-acre “city within a city.” The buildings are subject not only to Honor Award New York City Department of Buildings regulations, including New York City Local Law 10 of 1980 GE Building at Rockefeller and Local Law 11 of 1998 (LL10/LL11), but also to Landmark Commission restrictions, making Center - Restoration rehabilitation planning particularly challenging. Hoffmann Architects’ Master Plan addressed these considerations, while achieving even budgeting across the years. The award-winning rehabilitation program included facade and curtain wall restoration, roof replacements, waterproofing, and historic preservation for this National Historic Landmark and centerpiece of New York City. In conjunction with the Master Plan, Hoffmann Architects developed specific rehabilitation solutions for the Center’s structures, including: GE Building, Sculpture Restoration and Building Envelope Rehabilitation Radio City Music Hall, Roof Replacement and Facade Restoration La Maison Francaise and The British Empire Building, Facade Evaluations and Cleaning Channel Gardens and Lower Plaza/Skating Rink, Survey and Rehabilitation Design International Building, Facade Restoration and Roof Replacement Simon