Carson Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cultural Justice Approach to Popular Music Heritage in Deindustrialising Cities

International Journal of Heritage Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjhs20 A cultural justice approach to popular music heritage in deindustrialising cities Zelmarie Cantillon , Sarah Baker & Raphaël Nowak To cite this article: Zelmarie Cantillon , Sarah Baker & Raphaël Nowak (2020): A cultural justice approach to popular music heritage in deindustrialising cities, International Journal of Heritage Studies, DOI: 10.1080/13527258.2020.1768579 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1768579 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 27 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 736 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjhs20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HERITAGE STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1768579 A cultural justice approach to popular music heritage in deindustrialising cities Zelmarie Cantillon a,b, Sarah Baker c and Raphaël Nowak b aInstitute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, Parramatta, Australia; bGriffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia; cSchool of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Deindustrialisation contributes to significant transformations for local Received 2 April 2020 communities, including rising unemployment, poverty and urban decay. Accepted 10 May 2020 ‘ ’ Following the creative city phenomenon in cultural policy, deindustrialis- KEYWORDS ing cities across the globe have increasingly turned to arts, culture and Cultural justice; popular heritage as strategies for economic diversification and urban renewal. -

Toni Braxton Announces North American Fall Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TONI BRAXTON ANNOUNCES NORTH AMERICAN FALL TOUR Detroit (August 8, 2016) – Seven-time GRAMMY Award-winning singer, songwriter and actress Toni Braxton announces her North American tour. Kicking off on Saturday, October 8 in Oakland, Braxton will tour more than 20 cities, ending with a show in Atlantic City, NJ on Saturday, November 12. Most recently, Braxton released “Love, Marriage & Divorce,” a duets album with Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds. The album took off behind “Hurt You,” the Urban AC #1 duet hit co-written by Toni Braxton & Babyface (with Daryl Simmons and Antonio Dixon), and produced by Babyface. The two also shared the win for Best R&B Album at the 2015 GRAMMY Awards. Today, with over 67 million in sales worldwide and seven GRAMMY Awards, Braxton is recognized as one of the most outstanding voices of this generation. Her distinctive sultry vocal blend of R&B, pop, jazz and gospel became an instantaneous international sensation when she came forth with her first solo recording in 1992. Braxton stormed the charts in the 90’s with the releases of “Toni Braxton” and “Secrets,” which spawned the hit singles and instant classics; “Another Sad Love Song,” “Breathe Again,” “You’re Makin’ Me High,” and “Unbreak My Heart.” Today, Braxton balances the demands of her career with the high priorities of family, health and public service as she raises her two sons Denim and Diezel. This year Toni was the Executive Producer of the highly-rated Lifetime movie “Unbreak My Heart” which was based on her memoir and she is the star of the WEtv hit reality series Braxton Family Values in its fifth season. -

Ican/Ican Associates Presents the 2013 Child Abuse Prevention Poster Art Contest

ICAN/ICAN ASSOCIATES PRESENTS THE 2013 CHILD ABUSE PREVENTION POSTER ART CONTEST THEME: LET’S TAKE CARE OF OUR CHILDREN Contest is open to all 4th, 5th, and 6th Grade Students POSTERS MUST BE POSTMARKED BY: FRIDAY, MARCH 1, 2013 25 AWARDS FOR STUDENTS AND TEACHERS The Winners and Finalists will be honored in April 2013 Visit the ICAN Associates Website at: www.ican4kids.org APRIL IS NATIONAL CHILD ABUSE PREVENTION MONTH The ICAN/ICAN Associates Child Abuse Prevention Month Poster Contest focuses on the health and well-being of children and provides a comfortable forum for discussion in the classroom. This contest emphasizes the importance of child abuse prevention and gives children the ability to convey it to others through their art. Physical and emotional abuse can be reduced with education and awareness and the ICAN/ ICAN Associates Poster Contest is a public awareness campaign that addresses this critical need for protecting and educating our children. WINNERS, FINALISTS, AND THEIR TEACHERS will be invited to participate in the Announcement of Child Abuse Prevention Month when the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors meet in April, 2013. The posters of the winners and finalists have been previously exhibited at: ICAN Policy Committee Meeting Reception ICAN Annual Grief and Loss Conference State Department of Social Services Family Violence Division of the District Attorney’s Office, Criminal Courts Building HOWS Markets, Pasadena and North Hollywood Frances Howard Goldwyn Hollywood Library Los Angeles County Office of Education/Selected District Offices Los Angeles County Ed Edelman Children's Court ICAN/ICAN Associates “Nexus” Training Conference RULES pertaining to this event are enclosed. -

1 PLAYING AGAINST the ROLES SCENE 1 Scene 1

PLAYING AGAINST THE ROLES SCENE 1 Scene 1. The roof of Daniel and Estrella’s old apartment complex. DANIEL: Estrella! Why did you want to meet here? We’re going to miss the party! ESTRELLA: Can you believe how much this place has changed? DANIEL: I don’t even recognize it. ESTRELLA: It’s all so… white. It used to be filled with smells and sounds and people. DANIEL: Like the sounds of my terrible violin playing. ESTRELLA: I remember the smells that came from those windows. Mi abuela cooking (She pauses and smells the air) mole and fresh tortillas, and elote, and capirotada. DANIEL and ESTRELLA: and that awful Posole. They both make a face. DANIEL: We played for hours. ESTRELLA: With my Barbies. DANIEL: They were rich. ESTRELLA: and they had a swimming pool and like 10 kids and they always fought. DANIEL: Like my mom and dad. Before he left… ESTRELLA: but remember… we would run away and sneak out. DANIEL: And just lay up here and just look at the stars. They sit in silence remembering the past. DANIEL: You know… in a new place, you can be anyone you want. ESTRELLA: Easy for you to say, ”Dannie Beckerman football star.” (She laughs to herself) DANIEL: Speaking of… that party. You promised you’d come. ESTRELLA: I know. Just one more minute. 1 Scene 2 Scene 1. Friday Night. A teenage house party. We hear bumpin music, perhaps something by Drake or Kanye. DANIEL AND ESTRELLA enter the party. There are groups of mostly McGregor High School students scattered about the room laughing and talking loudly. -

Their Greatest Hits (1971-1975)”—The Eagles (1976) Added to the Registry: 2016 Essay by Marc Eliot (Guest Post)*

“Their Greatest Hits (1971-1975)”—The Eagles (1976) Added to the Registry: 2016 Essay by Marc Eliot (guest post)* The Eagles In 1971, the arrival of The Eagles signaled a major shift in popular musical tastes in America. If Woodstock was the funeral for both the music and the culture of a decade of drugged out, hippie, free love and cultish idealism, the Seventies was the decade of blatant decadence, political cynicism, sexual distrust, and rampant narcissism. No band represented both the rejection of the Sixties and the celebration of the Seventies more than its crown princes, the Eagles. Songs like “Lyin’ Eyes,” “Witchy Woman,” “One of These Nights,” and “Already Gone,” filled with spirited playing, close harmonies and an overlay of the Eagles’ war between the sexes, comprise four of the ten selections included in the initial compilation of Eagles’ hit songs from their first four albums, “Their Greatest Hits (1971-1975).” Ironically, although the Eagles’ laid-back sound was bright and natural as Southern California sunshine, none of the original four members were Golden State natives (Don Henley, vocalist, lyricist, drummer, was from Texas, bred on bluegrass and country music; Glenn Frey, vocalist, lyricist, rhythm guitar, pianist, came from the streets of Detroit, influenced by the music of Motown and mentored by Bob Seger; Randy Meisner, on bass, was a veteran bar band night sider out of Nebraska; Bernie Leadon, guitar, mandolin, banjo, was a Minnesotan who loved and loved to play classic country). Each migrated separately to Los Angeles, like lemmings, to The Troubadour, the musical and cultural ground zero club on Santa Monica Boulevard, owned and operated by Doug Weston, who favored putting on his stage country-rock bands and female vocalists. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ P --------- / CP060727 / CP060727 20th Anniversary Notes: The original art, done by Gary Grimshaw for ArtRock Gallery, in San Francisco Benefit: First American Tour 1969 Artist: Gary Grimshaw Promoter: Artrock Items: Original poster / CP060727 / CP060727 (11 x 17) Performers: : Led Zeppelin ------------------------------ GBR-G/G 1966 T-1 --------- 1966 / GBR G/G CP010035 / CS05131 Free Ticket for Grande Ballroom Notes: Grande Free Pass The "Good for One Free Trip at the Grande" pass has more than passing meaning. It was the key to distributing the Grande postcards on the street and in schools. Volunteers, mostly high-school-aged kids, would get a stack of cards to pass out, plus a free pass to the Grande for themselves. Russ Gibb, who ran the Grande Ballroom, says that this was the ticket, so to speak, to bring in the crowds. While posters in Detroit did not have the effect that posters in San Francisco had, and handbills were only somewhat better, the cards turned out to actually work best. These cards are quite rare. Artist: Gary Grimshaw Venue: Grande Ballroom Promoter: Russ Gibb Presents Items: Ticket GBR-G/G Edition 1 / CP010035 / CS05131 Performers: 1966: Grande Ballroom ------------------------------ GBR-G/G P-01 (H-01) 1966-10-07 P-1 -- ------- 1966-10-07 / GBR G/G P-01 (H-01) CP007394 / CP02638 MC5, Chosen Few at Grande Ballroom - Detroit, MI Notes: Not the very rarest (they are at lest 12, perhaps as 15-16 known copies), but this is the first poster in the series, and considered more or less essential. -

2018 River Madness Bracket

2018 River Madness Bracket First Round Second Round Swift 16 Entertaining 8 Fab Four Championship Fab Four Entertaining 8 Swift 16 Second Round First Round March 15-16 March 19-20 March 22-23 March 26-27 March 29 March 30 March 29 March 26-27 March 22-23 March 19-20 March 15-16 1 Elvis 70% Aerosmith 85% 1 Elvis 70% Elvis 70% Aerosmith 88% Aerosmith 85% 16 S. Miller Band 30% H. Lewis & News 15% 16 Elvis 58% Aerosmith 83% 8 Metallica 39% Elvis 70% Aerosmith 88% Springsteen 53% 8 Metallica 39% Styx 30% Springsteen 12% Springsteen 53% 9 Styx 61% Rod Stewart 47% 9 Elvis 66% Aerosmith 82% 5 Tom Petty 82% Van Halen 59% 5 Tom Petty 82% Tom Petty 78% Van Halen 61% Van Halen 59% 12 Bryan Adams 18% Elvis 58% Aerosmith 83% Chicago 41% 12 Tom Petty 42% Van Halen 17% 4 Madonna 67% Tom Petty 78% Van Halen 61% David Bowie 78% 4 Madonna 67% Madonna 22% David Bowie 39% David Bowie 78% 13 J. Browne 33% Tournament Of Legends A. Franklin 22% 13 Diamond Region Elvis 55% Aerosmith 45% Gold Region 6 REO 83% Bob Seger 75% 6 REO 83% REO Speedwagon 40% Bob Seger 42% Bob Seger 75% 11 The Police 17% Sheryl Crow 25% 11 Prince 56% Fleetwood Mac 41% 3 Prince 77% REO Speedwagon 40% AJ2F4 Fleet Mac 83% 3 Prince 77% Prince 60% Fleet Mac 58% Fleet Mac 83% 14 S & G 23% Elvis 66% Aerosmith 82% Temptations 17% 14 Prince 34% Guns N Roses 18% 7 Bee Gees 45% GNR 69% 7 Bee Gees 45% Pink Floyd 37% Guns N Roses 60% GNR 69% 10 Pink Floyd 55% Prince 56% Fleetwood Mac 41% Doobie Bros 31% 10 Elton John 44% Guns N Roses 59% 2 Elton John 87% Pink Floyd 37% Elvis 65% Guns N Roses 60% R. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

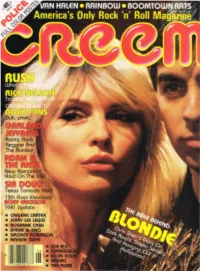

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Introduction in Their Thirty Years Together, the Grateful Dead Forever

Introduction In their thirty years together, the Grateful Dead forever altered the way in which popular music is performed, recorded, heard, marketed, and shared. Founding members Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann, Phil Lesh, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, and Bob Weir took the name Grateful Dead in 1965, after incarnations as Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions and The Warlocks. Despite significant changes in the band’s lineup, including the addition of Mickey Hart and the death of Ron McKernan, the band played together until Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995. From the beginning, the Grateful Dead distinguished themselves by their preference for live performance, musical and business creativity, and an unprecedented dedication to their fans. Working musicians rather than rock stars, the Dead developed a distinctive sound while performing as latter-day American troubadours, bringing audio precision to their live performances and the spontaneity of live performances to their studio work. Side-stepping the established rules of the recording industry, the Dead took control of the production and distribution of their music. With a similar business savvy, they introduced strategic marketing innovations that strengthened the bond with their fans. This exhibition, the first extensive presentation of materials from the Grateful Dead Archive housed at the University of California, Santa Cruz, testifies to the enduring impact of the Grateful Dead and provides a glimpse into the social upheavals and awakenings of the late twentieth century—a transformative period that profoundly shaped our present cultural landscape. Amalie R. Rothschild, Fillmore East Marquee, December 1969. Courtesy Amalie R. Rothschild Beginnings The Grateful Dead began their musical journey in the San Francisco Bay Area at a pivotal time in American history, when the sensibilities of the Beat generation coincided with the spirit of the burgeoning hippie movement. -

Press Release

OLYMPIA HAMMERSMITH ROAD LONDON W14 8UX +44 (0)20 7293 5522 WWW.SOTHEBYS.COM PRESS RELEASE Sotheby’s to host an exhibition of the art of Rock Art from Beat to Punk via Psychedelia including the infamous poster of the ‘Flying Eyeball’ measuring six feet high! INSPIRATIONAL TIMES - a major international exhibition tracing the history of one of the most influential periods through the Rock Art poster and graphic design in the 20th Century – will be held at Sotheby’s, Olympia from Sunday, January 5 through to Sunday, January 19, 2003. Based on the collection of fashion impresario Peter Golding, who is credited with creating the first stretch Jean in 1978, it is one of the largest archives of original rock and roll art in existence today. Peter began the collection after picking up a poster from a protest concert in Hyde Park, London in 1967 and has since amassed an extensive collection of original pieces of quintessential work by key artists and designers of the time ranging from sketches and illustrations to paintings, printing plates and first edition posters. Approximately 300 of these will be included in the exhibition. As well as having an impressive art collection, Peter Golding also owned the famous ACE boutique in London’s Kings Road, which during the 1970s and 1980s, catered to an international celebrity clientele of stage, screen and rock and roll stars. He is also an avid SOTHEBY’S: REGISTERED AT 34-35 NEW BOND STREET LONDON W1A 2AA NO. 874867 musician, very much dedicated to Blues and Jazz, and launched his CD “Stretching the Blues” in 1997 to a star studded audience at London’s Café de Paris.