New Products and Brand Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unilever (Breyer's & Good Humor) Using Genetical

Unilever (Breyer’s & Good Humor) Using Genetical by Paris Reidhead more and more consumers want to choose unadulterated food, it’s disappoint- Summary: ing to see Unilever investing in this unnecessary development in overly Genetically-modified fish proteins in Breyer’s Ice Cream processed food.” Unilever, the British-Dutch global consumer marketing products giant, is On July 4, 2006, Prof. Cummins wrote in the GM Watch website: the largest producer of ice cream and frozen novelties in the U.S. Unilever’s (http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=6706) brands sold in the U.S. include Breyer’s ice cream, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, that Unilever has been selling GM ice cream in the U.S., with FDA approval. Klondike ice cream bars, and Popsicle products. Unilever’s Good Humor is a major producer of ice cream bars and other frozen Specifically: Breyer’s Light Double-Churned, Extra Creamy Creamy novelty products mainly targeted to young children. The applications for approval Chocolate ice cream, as well as a Good Humor ice cream novelty bar, contain of GM ice cream have all ignored the impact of GM ice cream on children. the genetically-modified fish “antifreeze” proteins. In the FDA GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) application, Unilever’s scientists have patented, and the company is using ice cream Unilever’s main focus of safety was the allergenicity of the ice structuring pro- products sold in the U.S., Australia and New Zealand, “antifreeze” protein sub- tein from the pout fish. The main test was to examine effect of the ice structur- stances from the blood of the ocean pout (a polar ocean species). -

Companies That Do Test on Animals

COMPANIES THAT DO TEST ON ANIMALS Frequently Asked Questions Why are these companies included on the 'Do Test' list? The following companies manufacture products that ARE tested on animals. Those marked with a are currently observing a moratorium (i.e., current suspension of) on animal testing. Please encourage them to announce a permanent ban. Listed in parentheses are examples of products manufactured by either the company listed or, if applicable, its parent company. For a complete listing of products manufactured by a company on this list, please visit the company's Web site or contact the company directly for more information. Companies on this list may manufacture individual lines of products without animal testing (e.g., Clairol claims that its Herbal Essences line is not animal-tested). They have not, however, eliminated animal testing from their entire line of cosmetics and household products. Similarly, companies on this list may make some products, such as pharmaceuticals, that are required by law to be tested on animals. However, the reason for these companies' inclusion on the list is not the animal testing that they conduct that is required by law, but rather the animal testing (of personal-care and household products) that is not required by law. What can be done about animal tests required by law? Although animal testing of pharmaceuticals and certain chemicals is still mandated by law, the arguments against using animals in cosmetics testing are still valid when applied to the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. These industries are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency, respectively, and it is the responsibility of the companies that kill animals in order to bring their products to market to convince the regulatory agencies that there is a better way to determine product safety. -

Dreyer's Grand Ice Cream Business Time Line

Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream Business Time Line: DATE Event Description 4th Origins of ice cream being made… China, Persians faloodeh, Nero in Rome (62 AD) century BC 15th Spanish, Italian royalty and wealthy store mountain ice in pits for summer use Century 16th Ice Cream breakthrough is when Italians learn to make ice by immersing a bucket of Century water in snow and adding potassium nitrate… later just use common salt. 1700s Jefferson and Washington In US serving ice cream 1776 First US ice cream parlor in New York City and American colonists first to use the term ice cream 1832 Augustus Jackson (Black) in Philadelphia adds salt to lower temp. White House chef to a catering business. 1846 Nancy Johnson patented hand-crank freezer 1848 William Young patents an ice cream freezer 1851 Jacob Fussell in Seven Valleys, Pennsylvania established the first large-scale commercial ice cream plant… moved to Baltimore 1870s Development of Industrial Refrigeration by German engineer Carl von Linde 1904 Walk away edible cone at the St Louis World’s Fair 1906 William Dreyer made his first frozen dessert to celebrate his German ship's arrival in America. Made Ice Cream in New York then moves to Northern California began 20 year apprenticeship with ice cream makers like National Ice Cream Company and Peerless Ice Cream. 1921 Dreyer opens own ice creamery in Visalia and one first prize at Pacific Slope Dairy Show. 1920s – Dreyer taught ice cream courses at the University of California and served as an officer in 1930s the California Dairy Industries Association. -

Petition of the Procter & Gamble Company for Approval of Proposed Divestiture

PUBLIC RECORD VERSION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFÖRE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS: Deborah Platt Majoras, Chairman Pamela Jones Harbour Jon Leibowitz Wiliam E. Kovacic J. Thomas Rosch ) In the Matter of ) ) THEa corporation;PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY, ) ) ) Docket No. C-4151 and ) File No. 051-0115 ) THE GILLETTE COMPANY, ) a corporation., ) ) ) PETITION OF THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY FOR APPROVAL OF PROPOSED DIVESTITURE Pursuant to Section 2.41(f) of the Federal Trade Commission ("Commission" or "FTC") Rules of Practice and Procedure, 16 CF.R. § 2.41(f) (2005), and Paragraph II.A. of the final Decision and Order approved by the Commission in the above-captioned matter, The Procter & Gamble Company ("P&G") hereby fies this Petition for Approval of Proposed Divestitue ("Petition") requesting the Commission's approval of the divestitue of the APDO business, including Right Guard, Soft & Dri, Dry Idea, Natrel Plus, and Balance ("the APDO Assets") of The Gilette Company ("Gilette"), to The Dial Corporation ("Dial"), a subsidiar of Henkel KGaA ("Henkel"). .~ PUBLIC RECORD VERSION I. INTRODUCTION On September 23,2005, P&G and the Commission entered into an Agreement Containing Consent Orders, including an initial Decision and Order and an Order to Maintain Assets. On October 1,2005, pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger between P&G and Gilette dated Januar 27, 2005, P&G completed its acquisition of Gilette. After a period of public comment, on December 15, 2005, the Commission issued its final Decision and Order , ("Order") (with minor changes) and Order to Maintain Assets (without changes) (collectively, the "Consent Agreement"). At the same time it reissued its Complaint (also without changes). -

Unilever Annual Report 1994

Annual Review 1994 And Summary Financial Statement English Version in Childers Unilever Contents Directors’ Report Summary Financial Statement 1 Financial Highlights 33 Introduction 2 Chairmen’s Statement 33 Dividends 4 Business Overview 33 Statement from the Auditors 12 Review of Operations 34 Summary Consolidated Accounts 26 Financial Review 29 Organisation 36 Additional Information 30 Directors & Advisory Directors Financial Highlights 1994 1993 % Change % Change at constant atwrrent a* cOnSt.3nf exchange rates exchange rates exchange rates Results (Fl. million) Turnover 82 590 83 641 77 626 6 8 Operating profit 7 012 7 107 5 397 30 32 Operating profit before excepttonal items 7 294 6 763 6 8 Exceptional items (187) (1 366) Profit on ordinary activities before taxation 6 634 6 700 5 367 24 25 Net profit 4 339 4 362 3 612 20 21 Net profit before exceptional items 4 372 4 406 4 271 -~mpy~21 E Key ratios Operating margin before exceptional items (%) 8.7 8.7 Net profit margin before exceptional items (%) 5.3 5.5 Return on capital employed (%) 16.7 15.7 Net gearing (%) 22.7 24.8 Net interest cover (times) 12.2 12.8 Combined earnings per share Guilders per Fl. 4 of ordinary capital 15.52 12.90 20 Pence per 5p of ordinary capital 83.59 69.45 20 Ordinary dividends Guilders per Fl. 4 of ordinary capital 6.19 5.88 5 Pence per 5p of ordinary capital 26.81 25.03 7 Fluctuations in exchange rates can have a significant effect on Unilever’s reported results. -

List of the Top Dairy Processors in the Dairy 100

DAIRY 100 In Millions Code to Type: C=Cooperative; Pr=Privately-held company; Pu=Publicly-traded company; S=Subsidiary; An asterisk on a sales figure denotes a Dairy Foods estimate. SALES SALES COMPANY LOCATION DAIRY EXECUTIVE TYPE PARENT COMPANY, LOCATION FY END ‘11 ‘10 1. Dean Foods Co. Dallas, TX Gregg Engles, Chairman/CEO Pu 12/31/2011 $12,700 $12,123 Brands: Alpro (Europe), Alta Dena, Arctic Splash, Atlanta Dairies, Barbers, Barbe’s, Berkeley Farms, Broughton, Borden (licensed brand), Brown Cow, Brown’s Dairy, Bud’s Ice Cream, Chug, Country Charm, Country Churn, Country Delite, Country Fresh, Country Love, Creamland, Dairy Fresh, Dean’s, Dipzz, Fieldcrest, Foremost (licensed brand), Friendship, Gandy’s, Garelick Farms, Hershey’s (licensed brand), Horizon Organic, Hygeia, International Delight, Jilbert, Knudsen (licensed brand), LAND O LAKES (licensed brand), Land-O-Sun & design, Lehigh Valley Dairy Farms, Liberty, Louis Trauth Dairy Inc, Maplehurst, Mayfield, McArthur, Meadow Brook, Meadow Gold, Mile High Ice Cream, Model Dairy, Morning Glory, Nature’s Pride, Nurture, Nutty Buddy, Oak Farms, Over the Moon, Pet (licensed brand), Pog (licensed brand), Price’s, Provamel (Europe), Purity, Reiter, Robinson, Saunders, Schenkel’s All*Star, Schepps, Shenandoah’s Pride, Silk, Silk Pure Almond, Silk Pure Coconut, Stok, Stroh’s, Swiss Dairy, Swiss Premium, Trumoo, T.GLee, Tuscan, Turtle Tracks, Verifine, Viva. Products: Milk, cultured dairy, juice/drinks, water, creamers, whipping cream, ice cream mix, ice cream novelties. Plants: Fresh Dairy -

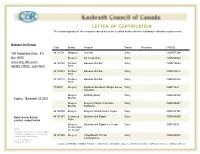

Letter of Certification the Following Products the Company Named Below Are Certified Kosher with the Following Certification Requirements

Letter of Certification The following products the company named below are certified kosher with the following certification requirements. Unilever Ice Cream Code Brand Product Status Requires UKD ID 909 Packerland Drive, P O 84113371 Magnum Almond Dairy COR707290 Box 19007 Breyers BL Creamsicle Dairy COR456463 Green Bay, Wisconsin 84127808 Fruttare Banana Milk Bar Dairy COR716543 UNITED STATES, 543079007 Fruit 84127433 Fruttare Banana Milk Bar Dairy COR870812 Fruit 84127812 Fruttare Banana Milk Bar Dairy COR953832 Fruit 7739701 Breyers Big Bear Sandwich (Single Serve) Dairy COR18821 Novelties Breyers Birthday Blast Dairy COR285799 Expires: November 30 2021 Blends Breyers Breyers Classic Chocolate Dairy COR974651 Blends Explosion 84125809 Breyers Breyers Vanilla Honey Yogurt Dairy COR387107 Rabbi Dovid Rosen 84121991 Creamery Butterscotch Ripple Dairy COR684050 Kashrus Administrator Style Breyers Butterscotch Ripple Ice Cream Dairy COR33532 Cream Style Note: Ice Cream Unauthorized use of the COR symbol is a violation of applicable food labeling statutes and copyright law. 84121990 Breyers CREAMERY STYLE Dairy COR286038 CHOCOLATE Letter # 280973214 October 01, 2021 3200 Dufferin Street #308 | Toronto, ON M6A 3B2 | 416.635.9550 | [email protected] | www.cor.ca Letter of Certification The following products the company named below are certified kosher with the following certification requirements. Unilever Ice Cream Code Brand Product Status Requires UKD ID 909 Packerland Drive, P O 84113936 Breyers Cadbury Caramilk Bar Dairy COR448415 Blends -

Case Study: Unilever1

CASE STUDY: UNILEVER1 1. Introduction Unilever is a British-Dutch company that operates in the market of consumer goods and sells its products in around 190 countries. Another remarkable fact is that they own more than 400 brands, what means an important diversification in both risk and the products they sell, among which there is food, personal care products and cleaning agents. In fact, twelve of these brands have sales of more than a billion euros. The importance of this multinational is reflected too in the fact 2.5 billion people use Unilever products every day, being part of their daily life. They also are responsible for the employment of 161,000 people in the different countries they operate. Finally, they believe in a sustainable business plan in which they reduce the environmental footprint and increase their positive social impact at the time they keep growing. 2. History Unilever was officially formed in 1929 by the merger of a margarine Dutch company and a British soapmaker. The margarine company of Netherlands was also a merger between the first margarine factory called in the world and another factory of the same product and from the same city, Oss, in the Netherlands. The soapmaker company revolutionized the market because it helped to a more hygienic society and the manufacturing of the product was wrapped. The name of the company is a fusion between the Dutch firm called Margarine Unie and the British firm called Lever Brothers. What Unilever did, was to expand its market locations to the American Latin and Africa. Moreover they widened the product areas to new sectors such as particular food and chemical products. -

Nutribalance-5000 Nutritional Scale

NutriBalance-5000 Nutritional Scale Carb. Guide Contains over 7000 additional food codes for carbohydrates! oz Max: 11lb d: 0.1oz MR M+ WT 9 Prot 7 8 Cal Sal 0 Tare 6 Fat Carb Col 4 5 Fibr 3 g/oz CLR 2 WT MC 1 How To Use This Manual: This manual provides a cross-reference of carbohydrate codes for the NutriBalance nutritional scale, based on the USDA National Nutrient Database Release 18. When using this manual, only the Carb function of the Nutribalance should be used. All other nutritional buttons such as Fiber, Prot, etc will not display accurate information. 1. To find the Carb Code for a food item, simply use the Acrobat Search function (Ctrl+F or Ctrl+Shift+F). Enter the name of the food item in the Search Field and hit Enter. Give the search time to complete. 2. Once you find your food item in the manual, select your code from the “Code to use” column, or the Code (Fiber Method) column. 3. Place the food item onto the weighing platform and enter the code using the keypad. Now press the Carb button. NOTE: The NutriBalance requires 3-digit input for the code to be accepted. Therefore, if the “Code to use” is 3, you should enter 003, etc. Code to use Code Carbo- Fiber_ Refuse_ Modified ( Fiber hydrt TD Pct Carbs (- Method) fiber) MILK SUBSTITUTES,FLUID,W/ 41 41 6.16 0 0 6.16 LAURIC ACID OIL MILK,WHL,3.25% MILKFAT 85 85 4.52 0 0 4.52 MILK,PRODUCER,FLUID,3.7% 819 819 4.65 0 0 4.65 MILKFAT MILK,RED 819 819 4.68 0 0 4.68 FAT,FLUID,2%MILKFAT,W/ADDED VIT A MILK,RED FAT,FLUID,2% 696 696 4.97 0 0 4.97 MILKFAT,W/ NONFAT MILK SOL&VIT A MILK,RED -

Disclaimer Notes to the Annual Report and Accounts This PDF

Disclaimer Notes to the Annual Report and Accounts This PDF version of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2005 is an exact copy of the document provided to Unilever’s shareholders. Certain sections of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2005 have been audited. Sections that have been audited are set out on pages 78 to 151, 157 to 172 and 174 to 177. The auditable part of the report of the Remuneration Committee as set out on page 69 has also been audited. The maintenance and integrity of the Unilever website is the responsibility of the Directors; the work carried out by the auditors does not involve consideration of these matters. Accordingly, the auditors accept no responsibility for any changes that may have occurred to the financial statements since they were initially placed on the website. Legislation in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands governing the preparation and dissemination of financial statements may differ from legislation in other jurisdictions. Disclaimer Except where you are a shareholder, this material is provided for information purposes only and is not, in particular, intended to confer any legal rights on you. This Annual Report and Accounts does not constitute an invitation to invest in Unilever shares. Any decisions you make in reliance on this information are solely your responsibility. The information is given as of the dates specified, is not updated, and any forward-looking statements are made subject to the reservations specified on page 4 of the Report. Unilever accepts no responsibility for any information on other websites that may be accessed from this site by hyperlinks. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,551,508 B2 Lee Et Al

US008551508B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,551,508 B2 Lee et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 8, 2013 (54) COSMETIC, PERSONAL CARE, CLEANING 6,224,888 B1 5/2001 Vatter et al. AGENT, AND NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENT 4. R ck $398, ity, al. ......... 433/217.1 a O. ca. COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS OF 7.857.046 B2 12/2010 Lovell et al. MAKING AND USING SAME 2002/0114768 A1 8/2002 Stoor et al. 2004/0228905 A1 * 1 1/2004 Greenspan et al. ........... 424,445 (75) Inventors: Sean Lee, Karlsruhe (DE); Susanna Kessler, Ergolding (DE); Oliver FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Forberich, Oberursel (DE); Claire CN 1290.158 A 4/2001 Buchwar, Wiesbaden (DE); David C. JP 2001-516709 10, 2001 Greenspan, Gainesville, FL (US) JP 2001-52.5779 12/2001 WO 96.10985 4f1996 (73) Assignee: Schott AG, Mainz (DE) WO 97.27148 7/1997 WO 99.13852 3, 1999 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO 99.37287 7, 1999 WO WO9937287 * 7/1999 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO OOf 15167 3, 2000 U.S.C. 154(b) by 919 days. WO OO/42977 T 2000 WO 00,76486 12/2000 (21) Appl. No.: 11/775,615 WO 01.03650 1, 2001 WO O 1/72145 10, 2001 (22) Filed: Jul. 10, 2007 WO O 1/72262 10, 2001 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (65) Prior Publication Data US 2007/0275O21 A1 Nov. 29, 2007 Fechner, J., “Bioactive Glasses as a Potential New Class of Anti Oxidative Ingredients for Personal Care Products.” International Journal for Applied Science 131: Apr. -

Chattanooga Times Free Press 10/04

Chattanooga Times Free Press 10/04 RedPlum 10/4 #1 (last coupon for both RP inserts expires 1/4/2016, OK to discard after that date) $1 off Abreva Conceal item, 6-12 ct. (exp 1/4/2016) $2 off Abreva product, 2g pump or tube (exp 1/4/2016) $3/1 Arnicare Gel 2.6 oz or Arthritis Tabs (exp 11/30) $1.50 off Biotene product (exp 11/4) $1.50/1 Bag or K-cup Box Community Coffee (exp 11/30) $4/2 Bags or K-cup boxes Community Coffee (exp 11/30) $1 off Dial kids or baby Body+Hair wash or foaming hand soap (exp 10/24) $1/2 Dial regular or For Men, or Tone bar soap 3 pk. +, or Dial Complete foaming hand soap 8 oz and refill hand soap, excl gel pumps (exp 10/24) $1/2 Dial regular or For Men, or Tone body wash excl trial size, or Dial regular or For Men or Tone 6-pk.+ bar soap, or Dial Acne Control body wash, bar soap, face wash or face scrub (exp 10/24) $2/2 Dry Idea deodorant (exp 11/4) $2 off Ester-C Gummies or Immune Charge item (exp 11/13) $3 off Ester-C tablets (exp 11/13) $2 off Garnier moisturizer (exp 10/31) $1 off Garnier shampoo, conditioner or treatment, excl 1.7-3 oz and trial size (exp 10/31) $1 off Garnier style item, excl 1.7-3 oz and trial size (exp 10/31) .50/1 Hefty cups (exp 12/31) $2 off L’Oreal Excellence Age Perfect haircolor, excl Excellence Creme (exp 10/31) $2/3 Mars fall harvest bags, 8.67 oz + (exp 10/31) $2 off MicroTouch Tough Blade razor with cartridges (exp 11/8) $2 off Nature’s Bounty Optimal Solutions item (exp 12/4) $1 off Nature’s Bounty vitamin or supplement (exp 12/4) $2/2 Old Spice hair, shampoo or 2in1 items, excl trial size (exp 10/18) $3 off Osteo Bi-Flex product, 28-60 ct, (exp 11/2) $5 off Osteo Bi-Flex product, 70 ct.