PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Booklet

ORIGINAL TELEVISION SCORE ADDITIONAL CUES FOR 4-PART VERSION 01 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors) 0.36 34 End of Episode 1 (Sarah Falls) 0.11 02 New Console 0.24 35 End of Episode 2 (Cybermen III variation) 0.13 03 The Eye of Orion 0.57 36 End of Episode 3 (Nothing to Fear) 0.09 04 Cosmic Angst 1.18 05 Melting Icebergs 0.40 37 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue (Premix) 1.22 06 Great Balls of Fire 1.02 07 My Other Selves 0.38 08 No Coordinates 0.26 09 Bus Stop 0.23 10 No Where, No Time 0.31 11 Dalek Alley and The Death Zone 3.00 12 Hand in the Wall 0.21 13 Who Are You? 1.04 14 The Dark Tower / My Best Enemy 1.24 15 The Game of Rassilon 0.18 16 Cybermen I 0.22 17 Below 0.29 18 Cybermen II 0.58 19 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen III 0.34 20 Raston Robot 0.24 21 Not the Mind Probe 0.10 22 Where There’s a Wind, There’s a Way 0.43 23 Cybermen vs Raston Robot 2.02 24 Above and Between 1.41 25 As Easy as Pi 0.23 26 Phantoms 1.41 27 The Tomb of Rassilon 0.24 28 Killing You Once Was Never Enough 0.39 29 Oh, Borusa 1.21 30 Mindlock 1.12 31 Immortality 1.18 32 Doctor Who Closing Theme - The Five Doctors Edit 1.19 33 Death Zone Atmosphere 3.51 SPECIAL EDITION SCORE 56 The Game of Rassilon (Special Edition) 0.17 57 Cybermen I (Special Edition) 0.22 38 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors Special Edition) 0.35 58 Below (Special Edition) 0.43 39 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue 1.17 59 Cybermen II (Special Edition) 1.12 40 The Eye of Orion / Cosmic Angst (Special Edition) 2.22 60 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen -

Doctor Who Classic Series Guide

Doctor who classic series guide Continue Author Robert Kuykendall 12 March 2013 Go to Doctor One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight. Check out the Reading Guide first! Last updated on January 12, 2020. Each season of Classic Doctor Who contains a series of series that consists of several episodes. Below is every Doctor Who serial classified and ranked. I got my list of episodes from a fantastic Wikipedia entry, a list of Doctor Who TV series. I also consulted Nerdist in the Doctor Who for Rookie series (First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Eleventh), Geeks Doom's 10th Classic 'Doctor Who' Adventure Worth Check Articles, and Doctor Who magazine's Big 200 Reader Poll to make sure I didn't present a single episode. Leave any suggestions for changes in the comments below. If you want to start on a later episode, Ritch and Space have a video that covers good starting points and watch habits. Another great option to start with is Doctors Revisited, a BBC series profiling each doctor and then revealed one of their classic stories. It's a great mix of backstory, commentary, and curated history: Reading Guide To Color Episodes Coordinated: Episode - Recommended Serial (I) Episode - Good Serial Episode - Normal Serial Episode - Boring or Bad Serial Episode - Series with Missing Parts (Audio, With More Images) Episode - Also Recommended Nerdist Also Recommended Nerdist Episode - Also Recommended By Geeks From The Doom Episode - Rank on The Doctor A: (I) on recommended TV series is their rank among other recommended episodes from this doctor. -

CS1021___Fulvue Driv

Anywhere USA: An American Portrait (Cinevolve Studios/MVD DVD) Page 1 of 2 Find Category: Home > Reviews > Comedy > Shorts > Anywhere USA: An American Portrait (Cinevolve Studios/MVD DVD) Anywhere USA: An American Portrait (Cinevolve Studios/MVD DVD) > Iron Man: Extremis/Spider - Woman: Agent Of S.W.O.R.D. Picture: B- Sound: C (Marvel Knights Double Extras: B Main Program: C+ Feature/Shout! Factory Blu- ray) > From Prada To Nada (2010/Lionsgate Blu-ray) + Hall From its success at the Pass (2011/Enlarged Edition – Sundance Film Festival, Extended Cut/Warner Blu-ray Anywhere USA is a series of w/DVD) + Muay Thai Fighter (2009/MagNet/Magnolia Blu- shorts skits that make fun of ray) + Wild Cherry (2008/Image American culture that you can Blu -ray find anywhere. Topics include > Black Moon (1975/Criterion Collection Blu -ray) American stereotypes, > Diary Of A Wimpy Kid: prejudices, racism, values and Rodrick Rules (2011/Fox Blu- more... To feature America's ray w/DVD) + Scholastic Sets: Good Night Gorilla + I’m Dirty worst at their best in a comic & I Stink (DVDs) + Team parodies and how Americans Umizoomi + Victorious – can laugh at their own Season One, Volume One (Nickelodeon DVDs idiosyncrasies. Watch a group > Martha Argerich & Mischa of amateur actors as they Maisky (Accentus) + Hector show you what it is to be in Berloiz: Les Troyens/Gergiev (Unitel Classica) + Pierre America. Boulez/The Cleveland Orchestra – Mahler: Des This film features 3 skits that are relate to each other but unconnected at Knaben Wunderhorn/Adagio from Symp. No. 10 (Acc the same time, Penance, Loss, and Ignorance. -

ISSUE # 19 the Fanzine Devoted to Doctor Who Gaming

THE FASA SPECIAL The fanzine devoted to Doctor Who Gaming „IN THE MUDS OF EDEN‰ ADVENTURE MODU ISSUE # 19 A COMPLETE LOOK AT THE FASA DOCTOR „PLASTERED IN PARIS‰ ADVENTURE MODULE GENCON 2012 CON REPORT - NEW NPC FEATURE and MORE... LE - „TIMEQUAKE‰ ADVENTURE MODULE WHO RPG - FASA WRITER INTERVIEWS 1 EDITOR’S NOTES CONTENTS Wow. This issue has been a big project for our staff. We are sure that many of you have wondered what EDITOR’S NOTES 2 the delay was all about for this issue, but it was simply REVIEW: Doctor Who: AiTS (11th Doctor Edition) 4 about getting you the best fanzine that we could. Our Cubicle 7 Product News– More Who on the Way 6 approach this issue was more investigative reporting and Defending the Earth is Set for Release 7 historical research than it was writing role‐playing re‐ A Complete Look at the FASA Doctor Who RPG 8 sources and adventure modules. For this issue we really Differences in the Editions of the FASA Who RPG 12 wanted to put together a fanzine that was as deeply in‐ FASA Doctor Who RPG Supplements 15 formative and complete as possible. Not just as a fanzine The Unpublished FASA Supplements 17 but as a research document about the FASA Doctor Who Researching the Existence of the Unpublished 18 role‐playing game. And that simply means that it took us More Research Method Information 19 longer than we hoped. However, our staff also feels like FASA Doctor Who Adventure Modules 20 this issue was worth the wait. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

DAVISON TV STORIES Castrovalva Four to Doomsday Kinda the Visitation Black Orchid Earthshock Time-Flight Arc Of

DAVISON TV STORIES Castrovalva Four to Doomsday Kinda The Visitation Black Orchid Earthshock Time-Flight Arc of Infinity Snakedance Mawdryn Undead Terminus Enlightenment The King’s Demons The Five Doctors Warriors of the Deep The Awakening Frontios Resurrection of the Daleks Planet of Fire The Caves of Androzani DAVISON ORIGINAL NOVELS Goth Opera The Crystal Bucephalus Lords of the Storm The Sands of Time Cold Fusion The Ultimate Treasure Zeta Major Deep Blue Divided Loyalties Imperial Moon The King of Terror Superior Beings Warmonger Fear of the Dark Empire of Death Blood and Hope Tip of the Tongue DAVISON TARGET NOVELISATIONS Doctor Who - Castrovalva Doctor Who - Four to Doomsday Doctor Who - Kinda Doctor Who and The Visitation Doctor Who - Black Orchid Doctor Who - Earthshock Doctor Who - Time-Flight Doctor Who - Arc of Infinity Doctor Who - Snakedance Doctor Who - Mawdryn Undead Doctor Who - Terminus Doctor Who - Enlightenment Doctor Who - The King’s Demons Doctor Who - The Five Doctors Doctor Who - Warriors of the Deep Doctor Who - The Awakening Doctor Who - Frontios Doctor Who - Planet of Fire Doctor Who - The Caves of Androzani DAVISON COMICS The Tides of Time The Stars Fell on Stockbridge The Stockbridge Horror Lunar Lagoon 4-Dimensional Vistas The Moderator The Lunar Strangers The Curse of the Scarab On the Planet Isopterus Blood Invocation The Forgotten - 5th Doctor segment Prisoners of Time 05: In Their Nature DAVISON ODDS & SODS The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot Peter Davison's Book of Alien Monsters Peter Davison's Book of Alien -

Doctor Who Classic Touches Down on Boxing Day

DOCTOR WHO CLASSIC TOUCHES DOWN ON BOXING DAY London, 20 December 2019: BritBox Becomes Home to Doctor Who Classic on 26th December Doctor Who fans across the land get ready to clear their schedules as the biggest Doctor Who Classic collection ever streamed in the UK launches on BritBox from Boxing Day. From 26th December, 627 pieces of Doctor Who Classic content will be available on the service. This tally is comprised of a mix of episodes, spin-offs, documentaries, telesnaps and more and includes many rarely-seen treasures. Subscribers will be able to access this content via web, mobile, tablet, connected TVs and Chromecast. 129 complete stories, which totals 558 episodes spanning the first eight Doctors from William Hartnell to Paul McGann, form the backbone of the collection. The collection also includes four complete stories; The Tenth Planet, The Moonbase, The Ice Warriors and The Invasion, which feature a combination of original content and animation and total 22 episodes. An unaired story entitled Shada which was originally presented as six episodes (but has been uploaded as a 130 minute special), brings this total to 28. A further two complete, solely animated stories - The Power Of The Daleks and The Macra Terror (presented in HD) - add 10 episodes. Five orphaned episodes - The Crusade (2 parts), Galaxy 4, The Space Pirates and The Celestial Toymaker - bring the total up to 600. Doctor Who: The Movie, An Unearthly Child: The Pilot Episode and An Adventure In Space And Time will also be available on the service, in addition to The Underwater Menace, The Wheel In Space and The Web Of Fear which have been completed via telesnaps. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

Costumes and Identities in Doctor Who (1982-1989)

Département des Études du Monde Anglophone (DEMA) Mémoire de Master 2 Recherche (2019-2020) “Oh, never mind about the clothes, they're easily changed.” – Costumes and identities in Doctor Who (1982-1989). Yorick Sarrail-Dupont Sous la direction de M. le Professeur Laurent Mellet Acknowledgments My utmost gratitude goes to Laurent Mellet, for his support and his faith in me. Under his guidance, I grew up a tremendous amount, both as an aspiring researcher and as a person. Without his patience, I would not have been able to make it through. I would like to thank Colin Baker and Nicola Bryant who agreed to help a person they had never met before and share some of their first-hand knowledge. My gratitude also goes to Matt West, who let me access some of the sources he had collected throughout the years, and to Nathalie Rivère de Carles and her sources on the Commedia dell’arte. Finally, I would like to thank the DEMA department, their encouragement, their feedback, and for the nurturing environment built by the various members of the department. Page 2 sur 110 Table des matières Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 I. Doctor Who: Around the Show ........................................................................................ 12 a) An overview of the history of Doctor Who ................................................................. -

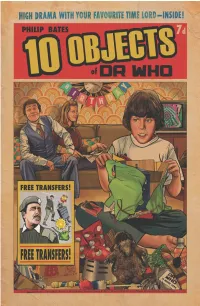

10 Objects of Dr

The right of Philip Bates to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. An unofficial Doctor Who Publication Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2021 Editor: Shaun Russell Editorial: Will Rees Cover and illustrations by Martin Baines Published by Candy Jar Books Mackintosh House 136 Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 1DJ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Come one, come all, to the Museum of ! Located on the SS. Shawcraft and touring the Seven Systems, right now! Are you a fully-grown human adult? I would like to speak to someone in charge, so please direct me to any children in the vicinity. No, no, that's not fair – I was programmed not to judge, for I am a simple advertisement bot, bringing you the best in junk mail. Are you always that short? No, don’t look at me like that: my creators were from Ravan-Skala, where the people are six hundred ft tall; you have to talk to them in hot air balloons, and the tourist information centre is made of one of their hats. -

Doctor Who Snakedance by Terrance Dicks the Essential Terrance Dicks Stories, As Chosen by Fans

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Snakedance by Terrance Dicks The essential Terrance Dicks stories, as chosen by fans. Coming this August is a two-volume celebration of this much-loved storyteller, collecting ten of Terrance Dicks’ best Doctor Who novels, as chosen by fans. You can pre-order The Essential Terrance Dicks Volumes One and Two now. Terrance Dicks was at the heart(s) of Doctor Who for over 50 years - from joining production of The Invasion in 1968 as a Script Editor to his final short story in 2019. Terrance wrote 64 Target novels from his first commission in 1973 to his last, published in 1990, helping introduce a generation of children to the pleasures of reading and writing, with fans including Neil Gaiman, Sarah Waters, Mark Gatiss, Alastair Reynolds, Russell T Davies, Steven Moffat, Frank-Cottrell Boyce, and Robert Webb, among many others. This special two-volume collection, published on the anniversary of Terrance’s death, features the very best of his Doctor Who Target novels as chosen by fans - from his first book, The Auton Invasion , to his masterwork, the 20th anniversary celebration story The Five Doctors , voted all- time favourite. With forewords by Frank Cottrell-Boyce and Robert Webb, The Essential Terrance Dicks is a masterclass in contemporary fiction, by a writer of unlimited imagination. Volume One contains, complete and unabridged: Doctor Who and the Dalek Invasion of Earth Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen Doctor Who and the Wheel in Space Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks. -

Released with Audio Only Anim

Updated – 7/26/15 Released Lost – Won’t be released unless found Unreleased A – Released with Audio only Anim – Released with Lost video replaced by Animation CD – Audio only released on CD (Doctor Who: The Lost TV Episodes: Collections) Release Scheduled The First Doctor – William Hartnell Season 1 001 – An Unearthly Child (1–4) 002 – The Daleks (1–7) 003 – The Edge of Destruction (1–2) 004 – Marco Polo (1–7) CD 005 – The Keys of Marinus (1–6) 006 – The Aztecs (1–4) 007 – The Sensorites (1–6) 008 – The Reign of Terror (1–3,4–5Anim,6) CD Season 2 009 – Planet of Giants (1–3) 010 – The Dalek Invasion of Earth (1–6) 011 – The Rescue (1–2) 012 – The Romans (1–4) 013 – The Web Planet (1–6) 014 – The Crusade (1,2A,3,4A) CD 015 – The Space Museum (1–4) 016 – The Chase (1–6) 017 – The Time Meddler (1–4) Season 3 018 – Galaxy 4 (1–2,3,4) CD 019 – Mission to the Unknown (1) 020 – The Myth Makers (1–4) CD 021 – The Daleks' Master Plan (1,2,3–4,5,6–9,10,11–12) CD 022 – The Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Eve (1–4) CD 023 – The Ark (1–4) 024 – The Celestial Toymaker (1–3,4) CD 025 – The Gunfighters (1–4) 026 – The Savages (1–4) CD 027 – The War Machines (1–4) Season 4 028 – The Smugglers (1–4) CD 029 – The Tenth Planet (1–3,4) CD The Second Doctor – Patrick Troughton 030 – The Power of the Daleks (1–6) CD 031 – The Highlanders (1–4) CD 032 – The Underwater Menace (1,2,3,4) CD 033 – The Moonbase (1A,2,3A,4) CD 034 – The Macra Terror (1–4) CD 035 – The Faceless Ones (1,2,3,4–6) CD 036 – The Evil of the Daleks (1,2,3–7) CD Season 5 037 – The Tomb of the