On Hard Facts and Misleading Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by CLP Research 1600 1700 1750

Spencer Compton 1600Copyright by CLP Research (1601-43) (2d Earl of Northampton); (Royalist/KIA fighting for King Charles I) Main Political Affiliation: Partial Genealogy of the Comptons = Mary Beaumont (1604-54) (of Ohio) 9 Others William Compton I 1763-83 Whig/Revolutionary (1622-94) 1789-1823 Republican (Emigrated from Northamptonshire, England to Long Island, New York, 1647); (moved to Middlesex co. New Jersey) 1824-33 National Republican = Mary Wilmot (1635-1713) See Wilmot of PA 1834-53 Whig 6 Others William Compton II Genealogy 1854- Republican (1649-1709) 1650 (born Long Island, New York); (moved to Middlesex co. New Jersey, then Monmouth co. NJ) = Mary Brown (1653-84) 9 Others Richard Compton (1667-1710); (merchant-store/farmer) = Providence Isselstyne (1664-1702) 6 Others Isselstyne Compton (1694-1763) 1700 = Orchie Altje Blaaw (1700-30) 7 Others Azariah Compton (1738-1825) (Rev War/Yorktown) = Margaret Mary Burlu 1750 (1760?-at least 1811) 7 Others Elias Compton (1788-1864); (farmer) (born Rosemont, Hunterdon co. NJ); (moved to Hamilton co. Ohio, 1816) Catheryne Die = = Bathsheba Hill 1800 (1790s?-1813) (1790-1832) 2 SonsWilson Martindale Compton 5 Others (1828-1908); (farmer) (born Springfield, Hamilton co. OH) = Elizabeth Hunt (1832-at least 1880) Rev. Elias Compton 4 Others 1850 (1856-at least 1927) (Wooster University professor of philosophy; dean) = Otelia Catheryne Augspurger (1858-1944) Dr. Karl Taylor Compton Dr. Wilson Martindale Comton 1 Daughter Arthur Holly Compton (1887-1954); (PhD/physics) (1890-1967); (PhD/physics) (1892-1962); (PhD/physics) (born Wooster, Wayne co. OH) (born Wooster, Wayne co. OH) (born Wooster, Wayne co. OH); (moved to Chicago, Cook co. -

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja the ZOOSEMIOTICS of SOCIALIZATION

University of Tartu Department of Semiotics Laura Kiiroja THE ZOOSEMIOTICS OF SOCIALIZATION: CASE-STUDY IN SOCIALIZING RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN TANGEN ANIMAL PARK, NORWAY Master’s Thesis Supervisors: Timo Maran, Ph.D Nelly Mäekivi, M.A Tartu 2014 CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….4 1. The theoretical aspects of keeping wild animals in captivity ………………………………7 1.1. The main arguments on the ethics of keeping animals in captivity……………….7 1.2. Modern viewpoints on animal welfare……………………………………………9 1.3. Modern viewpoints on animal behaviour………………………………………..13 1.3.1. Behavioural display and animal welfare……………………………….14 1.4. The role of enrichment in animal welfare………………………………………..17 1.4.1. The essence of animal training in zoos………………………………...19 1.5. The importance of human-animal relationships in the zoo………………………21 1.5.1. The importance of Umwelt consideration……………………………...23 1.5.1.1. The functional circle ………………………………………...24 1.5.2. The effect of zoo visitors on animal welfare…………………………..26 1.5.3. The effect of keeper-animal relationships on animal welfare………….28 1.6. Explaining animal communication…………………………………………........30 1.7. Socialization – a method of improving welfare of captive animals……………...36 1.7.1. The need for socialization……………………………………………...37 1.7.2. The basic mechanisms of socialization………………………………...38 2. The research methodology of a zoosemiotic approach to socialization …………………...40 2.1. Thick description of socialization………………………………………………..40 2.2. Actor-orientedness of the research……………………………………………….42 2.3. Participatory observation………………………………………………………...43 2.4. The dimensions of interpretations presented in the thesis ………………………44 3. Case-study of the socialization of Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)………………………………46 3.1. General methods of socialization………………………………………………..46 3.1.1. -

Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us About Human Language?

Linguistic Frontiers • 1(1) • 14-38 • 2018 DOI: 10.2478/lf-2018-0005 Linguistic Frontiers Representational Systems in Zoosemiotics and Anthroposemiotics Part I: What Have the So- Called “Talking Animals” Taught Us about Human Language? Research Article Vilém Uhlíř* Theoretical and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Philosophy and History of Sciences. Charles University. Viničná 7, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic Received ???, 2018; Accepted ???, 2018 Abstract: This paper offers a brief critical review of some of the so-called “Talking Animals” projects. The findings from the projects are compared with linguistic data from Homo sapiens and with newer evidence gleaned from experiments on animal syntactic skills. The question concerning what had the so-called “Talking Animals” really done is broken down into two categories – words and (recursive) syntax. The (relative) failure of the animal projects in both categories points mainly to the fact that the core feature of language – hierarchical recursive syntax – is missing in the pseudo-linguistic feats of the animals. Keywords: language • syntax • representation • meta-representation • zoosemiotics • anthroposemiotics • talking animals • general cognition • representational systems • evolutionary discontinuity • biosemiotics © Sciendo 1. The “Talking Animals” Projects For the sake of brevity, I offer a greatly selective review of some of the more important “Talking Animals” projects. Please note that many omissions were necessary for reasons of space. The “thought climate” of the 1960s and 1970s was formed largely by the Skinnerian zeitgeist, in which it seemed possible to teach any animal to master any, or almost any, skill, including language. Perhaps riding on an ideological wave, following the surprising claims of Fossey [1] and Goodall [2] concerning primates, as well as the claims of Lilly [3] and Batteau and Markey [4] concerning dolphins, many scientists and researchers focussed on the continuities between humans and other species, while largely ignoring the discontinuities and differences. -

THE NAKED APE By

THE NAKED APE by Desmond Morris A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Jonathan Cape Ltd. PRINTING HISTORY Jonathan Cape edition published October 1967 Serialized in THE SUNDAY MIRROR October 1967 Literary Guild edition published April 1969 Transrvorld Publishers edition published May 1969 Bantam edition published January 1969 2nd printing ...... January 1969 3rd printing ...... January 1969 4th printing ...... February 1969 5th printing ...... June1969 6th printing ...... August 1969 7th printing ...... October 1969 8th printing ...... October 1970 All rights reserved. Copyright (C 1967 by Desmond Morris. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mitneograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 30 Bedford Square, London Idi.C.1, England. Bantam Books are published in Canada by Bantam Books of Canada Ltd., registered user of the trademarks con silting of the word Bantam and the portrayal of a bantam. PRINTED IN CANADA Bantam Books of Canada Ltd. 888 DuPont Street, Toronto .9, Ontario CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, 9 ORIGINS, 13 SEX, 45 REARING, 91 EXPLORATION, 113 FIGHTING, 128 FEEDING, 164 COMFORT, 174 ANIMALS, 189 APPENDIX: LITERATURE, 212 BIBLIOGRAPHY, 215 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is intended for a general audience and authorities have therefore not been quoted in the text. To do so would have broken the flow of words and is a practice suitable only for a more technical work. But many brilliantly original papers and books have been referred to during the assembly of this volume and it would be wrong to present it without acknowledging their valuable assistance. At the end of the book I have included a chapter-by-chapter appendix relating the topics discussed to the major authorities concerned. -

DACETON Armigerum. Formica Armigera Latreille, 1802C: 244, Pl. 9, Fig

BARRY BOLTON’S ANT CATALOGUE, 2020 DACETON armigerum. Formica armigera Latreille, 1802c: 244, pl. 9, fig. 58 (w.) (no state data, probably Brazil). Type-material: syntype? workers (number not stated). Type-locality: Brazil: (no further data) (“collection du Stathouder”). Type-depository: MNHN? (not confirmed). Smith, F. 1853: 226 (q.m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1955a: 122 (l.). Combination in Atta: Guérin-Méneville, 1844a: 421; combination in Daceton: Perty, 1833: 136; Smith, F. 1853: 226. Status as species: Perty, 1833: 136; Guérin-Méneville, 1844a: 421; Smith, F. 1853: 226; Smith, F. 1858b: 160; Roger, 1862c: 290; Roger, 1863b: 40; Mayr, 1884: 38; Mayr, 1886c: 360; Dalla Torre, 1893: 149; Emery, 1894c: 140; Forel, 1895b: 136; Forel, 1907e: 3; Crawley, 1916b: 372; Mann, 1916: 452; Wheeler, W.M. 1916c: 9; Wheeler, W.M. 1923a: 4; Emery, 1924d: 316; Borgmeier, 1927c: 120; Borgmeier, 1934: 103; Kempf, 1961b: 514; Wilson, 1962b: 403; Kempf, 1970b: 335; Kempf, 1972a: 95; Bolton, 1995b: 168; Gronenberg, 1996: 2012; Bolton, 1999: 1655; Bolton, 2000: 18; Azorsa & Sosa- Calvo, 2008: 30; Sosa-Calvo, et al. 2010: 39 (in key); Bezděčková, et al. 2015: 117; Fernández & Serna, 2019: 851. Senior synonym of cordata: Roger, 1862c: 290; Mayr, 1863: 406; Roger, 1863b: 40; Dalla Torre, 1893: 149; Forel, 1895b: 136; Emery, 1924d: 317; Borgmeier, 1927c: 120; Kempf, 1972a: 95; Bolton, 1995b: 168. [Note: Mayr, 1863: 406, gives cordata as senior synonym, but armigerum has priority (Roger, 1863b: 40).] Distribution: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Trinidad, Venezuela. boltoni. Daceton boltoni Azorsa & Sosa-Calvo, 2008: 32, figs. 2, 4, 6, 8-16, 20-22 (w.) PERU, BRAZIL (Amazonas). -

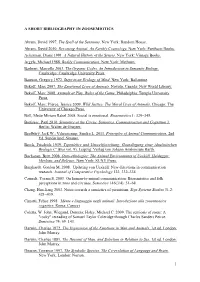

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

Check List 8(4): 722–730, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (Available at Journal of Species Lists and Distribution

Check List 8(4): 722–730, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Check list of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: PECIES S Formicidae) of the eastern Acre, Amazon, Brazil OF Patrícia Nakayama Miranda 1,2*, Marco Antônio Oliveira 3, Fabricio Beggiato Baccaro 4, Elder Ferreira ISTS 1 5,6 L Morato and Jacques Hubert Charles Delabie 1 Universidade Federal do Acre, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Natureza. BR 364 – Km 4 – Distrito Industrial. CEP 69915-900. Rio Branco, AC, Brazil. 2 Instituo Federal do Acre, Campus Rio Branco. Avenida Brasil 920, Bairro Xavier Maia. CEP 69903-062. Rio Branco, AC, Brazil. 3 Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Campus Florestal. Rodovia LMG 818, Km 6. CEP 35690-000. Florestal, MG, Brazil. 4 Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia. CP 478. CEP 69083-670. Manaus, AM, Brazil. 5 Comissão Executiva do Plano da Lavoura Cacaueira, Centro de Pesquisas do Cacau, Laboratório de Mirmecologia – CEPEC/CEPLAC. Caixa Postal 07. CEP 45600-970. Itabuna, BA, Brazil. 6 Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz. CEP 45650-000. Ilhéus, BA, Brazil. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The ant fauna of state of Acre, Brazilian Amazon, is poorly known. The aim of this study was to compile the species sampled in different areas in the State of Acre. An inventory was carried out in pristine forest in the municipality of Xapuri. This list was complemented with the information of a previous inventory carried out in a forest fragment in the municipality of Senador Guiomard and with a list of species deposited at the Entomological Collection of National Institute of Amazonian Research– INPA. -

Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation

THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PRODUCED IN GUIANAS COLLABORATION VERZICHT APERWITH: Ç 2016 Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 WWF-Guianas Global Wildlife Conservation Guyana Office PO Box 129 285 Irving Street, Queenstown Austin, TX 78767 USA Georgetown, Guyana [email protected] www.wwfguianas.org [email protected] Text: Juliana Persaud, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Concept: Francesca Masoero, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Design: Sita Sugrim for Kriti Review: Brian O’Shea, Deirdre Jaferally and Indranee Roopsind Map: Oronde Drakes Front cover photos (left to right): Rupununi Savannah © Zach Montes, Giant Ant Eater © Gerard Perreira, Red Siskin © Meshach Pierre, Jaguar © Evi Paemelaere. Inside cover photo: Gallery Forest © Andrew Snyder. OF BIODIVERSITYTHE SOUTHERN RUPUNUNI SAVANNAH. Guyana-South America. World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 This booklet has been produced and published thanks to: 1 WWF Biodiversity Assessment Team Expedition Southern Rupununi - Guyana. The Southern Rupununi Biodiversity Survey Team / © WWF - GWC. Biodiversity Assessment Team (BAT) Survey. This programme was created by WWF-Guianas in 2013 to contribute to sound land- use planning by filling biodiversity data gaps in critical areas in the Guianas. As far as possible, it also attempts to understand the local context of biodiversity use and the potential threats in order to recommend holistic conservation strategies. The programme brings together local knowledge experts and international scientists to assess priority areas. With each BAT Survey, species new to science or new country records are being discovered. This booklet acknowledges the findings of a BAT Survey carried out during October-November 2013 in the southern Rupununi savannah, at two locations: Kusad Mountain and Parabara. -

The “Tolerant Chimpanzee”—Towards the Costs and Benefits of Sociality in Female Bonobos

Behavioral The official journal of the ISBE Ecology International Society for Behavioral Ecology Behavioral Ecology (2018), 29(6), 1325–1339. doi:10.1093/beheco/ary118 Original Article The “tolerant chimpanzee”—towards the Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article-abstract/29/6/1325/5090310 by MPI evolutionary Anthropology user on 07 January 2019 costs and benefits of sociality in female bonobos Niina O. Nurmi,a,b, Gottfried Hohmann,b Lucas G. Goldstone,c Tobias Deschner,b and Oliver Schülkea,d aDepartment of Behavioral Ecology, JFB Institute for Zoology/Anthropology, University of Göttingen, Germany, bDepartment of Primatology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Germany, cGraduate School of Systemic Neurosciences, Ludwig Maximilians University, Germany, and dResearch Group Social Evolution in Primates, German Primate Center, Leibniz Institute for Primate Research, Göttingen, Germany Received 7 December 2017; revised 26 July 2018; editorial decision 28 July 2018; accepted 8 August 2018; Advance Access publication 4 September 2018. Humans share an extraordinary degree of sociality with other primates, calling for comparative work into the evolutionary drivers of the variation in social engagement observed between species. Of particular interest is the contrast between the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus), the latter exhibiting increased female gregariousness, more tolerant relationships, and elab- orate behavioral adaptations for conflict resolution. Here, we test predictions from 3 socioecological hypotheses regarding the evo- lution of these traits using data on wild bonobos at LuiKotale, Democratic Republic of Congo. Focusing on the behavior of co-feeding females and controlling for variation in characteristics of the feeding patch, food intake rate moderately increased while feeding effort decreased with female dominance rank, indicating that females engaged in competitive exclusion from high-quality food resources. -

The Legacy of Mildred Dresselhaus, the Queen of Carbon

The legacy of Mildred Dresselhaus, the Queen of Carbon Zeila Zanolli RWTH Aachen June 7, 2017 - ETSF Young Researchers Meeting, Tarragona Mildred Dresselhaus Laid the foundations for C nanotechnology: Pioneer of experimental techniques to study 2D materials Predicted the possibility and characteristics of CNTs (band structure, …) Low-dimensional thermolectrics: model of thermal transport in nanostructures, energy materials, electronic properties, phonons, electron-phonon interactions, … Her work has been crucial for developing lithium-ion batteries, electronic devices, renewable-energy generators, … [email protected] Millie: Institute Professor at MIT > 1700 publications h-index 135 > 25 prestigious awards 28 honorary doctorates Supervised >60 PhD 57 years at MIT [email protected] How did she started? [email protected] Millie: a tale of persistence 1930: born in Brooklyn lived in the Bronx family of immigrants, quite poor during the Great Depression 1936 ( 6 y): got a scholarship for a Music school and heard about the Hunter College “My teachers didn’t think it was possible to get in. But Hunter sent me a practice exam, and I studied what I needed to know to pass the exam.” at Hunter, Rosalyn Yalow (future Nobel laureate) encouraged Millie in pursuing a scientific career. 1951 (21 y): Bachelor, Hunter College, New York [email protected] Millie as Young Researcher 1953 (23 y): MA, Radcliffe College on a Fulbright Fellowship, Cambridge (MA) & Harvard 1958 (28 y): PhD, University of Chicago on the properties of superconductors in a magnetic field. Daily chats with E. Fermi. “My nominal thesis adviser told me in 1955 that women had no place in physics” I told him that I was not expecting to have others show interest in my work. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Journal of School Violence

Journal of School Violence eHAWORTH® Electronic Text is provided AS IS without warranty of any kind. The Haworth Press, Inc. further disclaims all implied warranties including, without limitation, any implied warranties of merchantability or of fitness for a particular purpose. The entire risk arising out of the use of the Electronic Text remains with you. In no event shall The Haworth Press, Inc., its authors, or anyone else involved in the creation, production, or delivery of this product be liable for any damages whatsoever (including, without limitation, damages for loss of business profits, business interruption, loss of business information, or other pecuniary loss) arising out of the use of or inability to use the Electronic Text, even if The Haworth Press, Inc. has been advised of the possibility of such damages. EDITOR EDWIN R. GERLER, Jr., Professor, Counselor Education Program, College of Education, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC ASSOCIATE EDITORS PAMELA L. RILEY, Executive Director, National Association of Students Against Violence Everywhere (SAVE), Raleigh, NC JOANNE McDANIEL, Director, Center for the Prevention of School Violence, Raleigh, NC COLUMN EDITOR, E-SITES FOR SAFE SCHOOLS REBECCA R. REED, Ahlgren Associates, Raleigh, NC EDITORIAL BOARD DAVID P. ADAY, Jr., Department of Sociology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA RON AVI ASTOR, School of Social Work, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA RAMI BENBENISHTY, Paul Baerwald School of Social Work, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel ILENE R. BERSON, Department of Child and Family Studies, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL CATHERINE BLAYA-DEBARBIEUX, Universite Victor Segalen Bordeaux 2, Bordeaux Cedex, France CHERYL L.