Battered Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Wonderful World of Slapstick

THE THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF Georgia State Bo»r* of Education AN. PR,CLAun\;v eSupt of School* 150576 DECATUR -DeKALB LIBRARY REGIONAI SERVICE ROCKDALE COUNTY NEWTON COUNTY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Media History Digital Library http://archive.org/details/mywonderfulworldOObust MY WONDERFUL WORLD OF SLAPSTICK MY WO/VDERFUL WORLD OF SLAPSTICK BUSTER KEATON WITH CHARLES SAMUELS 150576 DOVBLEW& COMPANY, lNC.,<k*D£H C(TYt HlW Yo*K DECATUR - DeKALB LIBRARY REGiOMA! $&KZ ROCKDALE COUNTY NEWTON COUNTY Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 60-5934 Copyright © i960 by Buster Keaton and Charles Samuels All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition J 6>o For Eleanor 1. THE THREE KEATONS 9 2. I BECOME A SOCIAL ISSUE 29 3. THE KEATONS INVADE ENGLAND 49 4. BACK HOME AGAIN IN GOD'S COUNTRY 65 5. ONE WAY TO GET INTO THE MOVIES 85 6. WHEN THE WORLD WAS OURS 107 7. BOFFOS BY MAN AND BEAST 123 8. THE DAY THE LAUGHTER STOPPED 145 9. MARRIAGE AND PROSPERITY SNEAK UP ON ME 163 10. MY $300,000 HOME AND SOME OTHER SEMI-TRIUMPHS 179 11. THE WORST MISTAKE OF MY LIFE 199 12. THE TALKIE REVOLUTION 217 13. THE CHAPTER I HATE TO WRITE 233 14. A PRATFALL CAN BE A BEAUTIFUL THING 249 15. ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL 267 THE THREE KeAtOnS Down through the years my face has been called a sour puss, a dead pan, a frozen face, The Great Stone Face, and, believe it or not, "a tragic mask." On the other hand that kindly critic, the late James Agee, described my face as ranking "almost with Lin- coln's as an early American archetype, it was haunting, handsome, almost beautiful." I cant imagine what the great rail splitter's reaction would have been to this, though I sure was pleased. -

Buster Keaton Shorts One Week – 1920 the Scarecrow – 1920 the ‘High Sign’ – 1921 Cops - 1922

Buster Keaton Shorts One Week – 1920 The Scarecrow – 1920 The ‘High Sign’ – 1921 Cops - 1922 COMPONENT 2: SECTION C SILENT CINEMA S AREAS FOR STUDY S FILM FORM S MEANING AND RESPONSE (INCLUDING REPRESENTATION OF REALISM) S CONTEXTS S CRITICAL DEBATES Why you are studying Silent Cinema S Communicating narrative through purely visual means is an art form in itself (think about a painting e.g. the many ‘narratives’ about the Mona Lisa) S Buster Keaton’s films explored ‘big man v little man’ narratives during a time of great industrial progress (modernism) pre the Great Depression/Wall Street global crash in 1929 – Chaplin/Harold Lloyd as contemporaries, see 1921 Never Weaken S Representations very theatrical, OTT and stylised reflecting a vaudeville tradition (theatre based on comedy situations) S Cops is the main film in this resource Cops (1922) S The Cops has several ‘big gags’ – personal favourite, Policeman ‘punched’ twice Example Questions: 30 min, 20 mark question Discuss how your chosen film or films reflect aesthetic qualities associated with a particular film movement Discuss how far your chosen film or films reflect cultural contexts associated with a particular film movement To what extent can it be said that your chosen film movement represents an expressionistic, as opposed to a realist approach to filmmaking? Make detailed reference to examples from the silent film or films you have studied “Films without recorded speech can succeed brilliantly in communicating ideas and emotions”. How true is this statement in relation to the silent film or films you have studied? Grand buildings – LA as American city, progress/modernity protected by The Police Big man v Little man. -

Film Preservation & Restoration Workshop

FILM PRESERVATION & RESTORATION WORKSHOP, INDIA 2016 1 2 FILM PRESERVATION & RESTORATION WORKSHOP, INDIA 2016 1 Cover Image: Ulagam Sutrum Valiban, 1973 Tamil (M. G. Ramachandran) Courtesy: Gnanam FILM PRESERVATION OCT 7TH - 14TH & RESTORATION Prasad Film Laboratories WORKSHOP 58, Arunachalam Road Saligramam INDIA 2017 Chennai 600 093 Vedhala Ulagam, 1948, Tamil The Film Preservation & Restoration Workshop India 2017 (FPRWI 2017) is an initiative of Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) and The International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, L’Immagine Ritrovata, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Prasad Corp., La Cinémathèque française, Imperial War Museums, Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, The National Audivisual Institute of Finland (KAVI), Národní Filmový Archiv (NFA), Czech Republic and The Criterion Collection to provide training in the specialized skills required to safe- guard India’s cinematic heritage. The seven-day course designed by David Walsh, Head of the FIAF Training and Outreach Program will cover both theory and practical classes in the best practices of the preservation and restoration of both filmic and non-filmic material and daily screenings of restored classics from around the world. Lectures and practical sessions will be conducted by leading archivists and restorers from preeminent institutions from around the world. Preparatory reading material will be shared with selected candidates in seven modules beginning two weeks prior to the commencement of the workshop. The goal of the programme is to continue our commitment for the third successive year to train an indigenous pool of film archivists and restorers as well as to build on the movement we have created all over India and in our neighbouring countries to preserve the moving image legacy. -

+ Vimeo Link for ALL of Bruce Jackson's and Diane Christian's Film

Virtual February 2, 2021 (42:1) Buster Keaton and Clyde Bruckman: THE GENERAL (1927, 72 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries + Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the Spring 2021 BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to The General Zoom link for all Fall 2020 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 National Film Preservation Board, USA 1989 Directed by Buster Keaton, Clyde Bruckman, Written by Buster Keaton, Clyde Bruckman, (written by), Al Boasberg, Charles Henry Smith (adapted by), William Pittenger (book, memoir "The Great BUSTER KEATON (b. Joseph Frank Keaton VI on Locomotive Chase") (uncredited) and Paul Girard October 4, 1895 in Piqua, Kansas—d. February 1, Smith (uncredited) 1966 in Los Angeles, CA) was born in a boarding Produced Buster Keaton, Joseph M. Schenck house where his parents, Joseph Hallie Keaton and Music Joe Hisaishi Myra Cutler Keaton, were touring with a medicine Cinematography Bert Haines, Devereaux Jennings show. He made his debut at the age of nine months Film Editing Buster Keaton, Sherman Kell when he crawled out of the dressing room onto the Art Direction Fred Gabourie stage, and he became part of the act when he was three. The young Keaton got his nickname within the Cast first two years of his life when he fell down a flight of Buster Keaton…Johnnie Gray stairs and landed unhurt and unfazed. -

David L. Smith Collection Ca

Collection # P 0568 OM 0616 CT 2355–2368 DVD 0866–0868 DAVID L. SMITH COLLECTION CA. 1902–2014 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Processed by Barbara Quigley and Courtney Rookard February 27, 2017 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 6 boxes of photographs, 1 OVA graphics box, 1 OVB COLLECTION: photographs box, 4 flat-file folders of movie posters; 1 folder of negatives; 9 manuscript boxes; 7 oversize manuscript folders; 1 artifact; 14 cassette tapes; 3 CDs; 1 thumb drive; 18 books COLLECTION 1902–2014 DATES: PROVENANCE: Gift from David L. Smith, July 2015 RESTRICTIONS: Any materials listed as being in Cold Storage must be requested at least 4 hours in advance. COPYRIGHT: The Indiana Historical Society does not hold the copyright for the majority of the items in this collection. REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2015.0215, 2017.0023 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH David L. Smith is Professor Emeritus of Telecommunications at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, where he taught for twenty-three years. He is the author of Hoosiers in Hollywood (published by the Indiana Historical Society in 2006), Sitting Pretty: The Life and Times of Clifton Webb (University Press of Mississippi, 2011), and Indianapolis Television (Arcadia Publishing, 2012). He was the host of a series called When Movies Were Movies on WISH-TV in Indianapolis from 1971–1981, and served as program manager for the station for twenty years. -

Mimodiegetic and Volodiegetic Levels of Diegesis, Together with Variable Frame Rates, As Tools to Define a Tentative Early Film Language

Lund University Christoffer Markholm Centre for Languages and Literature FiMN09, spring 2017 Master Program in Film and Media History Master’s Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Erik Hedling Seminar Date: 31-05-2017 Mimodiegetic and Volodiegetic Levels of Diegesis, Together with Variable Frame Rates, as Tools to Define a Tentative Early Film Language Abstract This thesis focuses on the era of early film, with the aim to address an almost forgotten film language. Three aspects have been taken into account—variable frame rates, suppressed sound and hearing, and projection speeds—to analyze several examples of film to ascertain the techniques used by early filmmakers. I have also applied my findings of the techniques of yesteryear to contemporary films that have tried to imitate the early era production methods, in order to present the possibilities and difficulties in reproducing and utilizing the “old” language. The thesis also examines what separated the early era from the modern era, thus identifying future avenues of research. In so doing, I have introduced two novel diegetic terms, namely mimodiegetic and volodiegetic, with the former referring to sound imitating the visuals and the latter relating to a volatile sound rising from the image. Neither of the terms represents a technique, or, for that matter, are restricted to the early era—both rather provide a means to define a specific technique. Finally, based on my findings, I argue that the early film language is problematic to utilize fully today but that it is, at the same time, not confined to the early era. Keywords: silent era, diegesis, frame rate, frames per second, early film, intertitles, projection, Girl Shy, The Movies, Fiddlesticks, One Week, Neighbors, Easy Street, Ask Father, The Artist, La Antena, Dr. -

Buster Keaton O Mundo É Um Circo

26 set > 14 out 2018 ccbb rj 09 out > 28 out 2018 ccbb brasília 11 out > 05 nov 2018 ccbb são Paulo apresentação 9 artigos O cinema, arte do espaço 17 ÉRIC ROHMER Sobre o filme cômico, e em especial sobre Buster Keaton 21 JUDITH ÉRÈBE O mecânico da pantomima 39 ANDRÉ MARTIN biografia + TRAJETÓRIA Cronologia de Buster Keaton 61 Entrevistas com Buster Keaton 91 Os Estúdios Keaton 111 DAVID ROBINSON análises A mise-en-scène de Keaton 151 JEAN-PIERRE COURSODON Mise-en-scène, visão de mundo e consciência estética 179 JEAN-PIERRE COURSODON A gag 195 JEAN-PATRICK LEBEL FILMOGRAFIA COMENTADA 227 FILMOGRAFIA 251 4 O Banco do Brasil apresenta Buster Keaton – O Mundo é um Circo, a mais completa mostra retrospectiva dedicada ao ator e diretor norte-americano já vista no país. A trajetória de Keaton no cinema mudo foi marcada pela interpretação de personagens impassíveis em suas comédias, característica inovadora que revolucionou o mundo da séti- ma arte. Os trabalhos de atuação e direção do artista serão lembrados por meio da exibição de 70 filmes, em película e formatos digitais, além de sessões com acompanhamento mu- sical ao vivo, com audiodescrição, masterclass, curso, debate e livro-catálogo. Com a realização deste projeto, o CCBB reafirma o seu apoio à arte cinematográfica, mantém o seu compromisso com uma programação de qualidade e oferece ao público a oportu- nidade de imergir na obra de Buster Keaton – um dos nomes mais emblemáticos do cinema mudo. Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil 6 7 apresentação DIOGO CAVOUR (com colaboração de Ruy Gardnier) Buster Keaton faz parte do hall dos grandes atores-autores do cinema silencioso. -

Reel Architecture Film Series Summer 2005 National Building Museum

Reel Architecture Film Series Summer 2005 National Building Museum Between July 9 and August 24, 2005, the Museum will present The Reel Architecture Film Series. Inspired by the summer film series Screen on the Green held on the National Mall, Reel Architecture will take place in the Museum’s expansive Great Hall. Guests will be able to spread blankets and pillows among the Museum’s colossal Corinthian columns and enjoy inspiring films in a relaxed atmosphere, rain or shine. The Reel Architecture Film Series is the Museum’s first annual film series dedicated to the relationship between architecture and film. This free series will be launched the weekend of July 9th and 10th by two days of movies dedicated to representations of Los Angeles on screen. After opening weekend, the Museum will present weekly screenings of classic American films dedicated to themes found in past National Building Museum exhibitions—such as sustainable architecture and the do-it-yourself movement. Several features will be opened by short documentary or comedy films. During the Museum’s seven-week, Wednesday night series, doors will open at 7:15 pm and live music will precede each screening. Outside food and non-alcoholic beverages are allowed. Concessions will also be provided by the National Building Museum's nonprofit neighbor, Third & Eats. Proceeds will benefit their mission of training the unemployed and providing aid to the poor and homeless. Floor space is first come first served, with some chairs available, so bring your blankets and pillows and spread out on the carpet of the (air-conditioned) Great Hall! OPENING WEEKEND CELEBRATION OF LOS ANGELES ON SCREEN LIBERTY Directed by Leo McCarey, starring Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy 1929, 20 minutes, Not rated THE LONG GOODBYE Directed by Robert Altman, starring Elliott Gould 1973, 112 minutes, Rated R L.A. -

Untitled Review, New Yorker, September 19, 1938, N.P., and “Block-Heads,” Variety, August, 31, 1938, N.P., Block-Heads Clippings File, BRTC

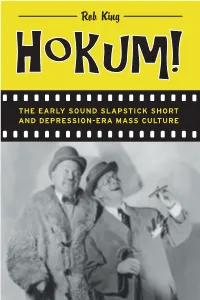

Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Ahmanson Foundation Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. Hokum! Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture Rob King UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2017 by Robert King This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: King, Rob. Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.28 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data King, Rob, 1975– author. Hokum! : the early sound slapstick short and Depression-era mass culture / Rob King. Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Diciembre 2008

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 91 3691125 Fax: 91 4672611 (taquilla) [email protected] 91 369 2118 http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html (gerencia) Fax: 91 3691250 MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala diciembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2008 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 17.00 – 00.30 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.30 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico DICIEMBRE 2008 Historias en común: 40 años / 50 películas del cine iberoamericano (I) O Dikhipen - Gitanos en el cine Muestra de cine gallego Buster Keaton (I) Buzón de sugerencias: Henri-Georges Clouzot (I) Muestra de cortometrajes de la PNR Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. Los que aparecen en cursiva corresponden a una traducción literal del original o a títulos habitualmente utilizados en español. -

Buster Keaton, OUR HOSPITALITY (1923, 73 Min)

August 31, 2010 (XXI:1) Buster Keaton, OUR HOSPITALITY (1923, 73 min) Directed by John G. Blystone and Buster Keaton Story, scenario and titles by Jean C. Havez, Clyde Bruckman & Joseph A. Mitchell Produced by Joseph M. Schenck legendary producers. He produced all of Keaton’s great films Cinematography by Gordon Jennings and Elgin Lessley (through Steamboat Bill, Jr). Some others of his 90 films were As You Like It (1936), Under Two Flags (1936), Hallelujah, I'm a Bum Joe Roberts...Joseph Canfield (1933), Rain (1932), Indiscreet (1931), Camille (1927), The Ralph Bushman...Canfield's Son Duchess of Buffalo (1926), Go West (1925), The Frozen North Craig Ward...Canfield's Son (1922), My Wife's Relations (1922), The Paleface (1922), She Monte Collins...The Parson Loves and Lies (1920), Convict 13 (1920), The Probation Wife Joe Keaton...The Engineer (1919), Her Only Way (1918), Coney Island (1917), His Wedding Kitty Bradbury...Aunt Mary Night (1917), and Panthea (1917). He won an honorary Academy Natalie Talmadge...The Girl - Canfield's Daughter Award in 1953. Buster Keaton Jr....Willie McKay - 1 Year Old Buster Keaton...Willie McKay - 21 Years Old CLYDE BRUCKMAN (20 September 1894, San Bernardino, California— 4 January 1955, Hollywood, suicide) wrote the BUSTER KEATON (Joseph Frank screenplays for about 60 lightweight films, the last Keaton VI, 4 October 1895, Piqua, of which was Goof on the Roof 1953. He directed 21 Kansas—1 February 1966, Los films, the last of them Man on the Flying Trapeze Angeles, lung cancer) wrote about 30 1935. Some of the others were Horses' Collars 1935, films, directed nearly 50, and acted in The Fatal Glass of Beer 1933, Everything's Rosie more than 140 films and television 1931, Leave 'Em Laughing 1928, Should Tall Men series, often playing himself. -

Aportacions Del So Al Cinema: Sonorització D’Un Curtmetratge Mut

Grau en Mitjans Audiovisuals Aportacions del so al cinema: Sonorització d’un curtmetratge mut Memòria DAVID PACHECO MODESTO PONENT: ÀNGEL VALVERDE VILABELLA PRIMAVERA 2016 Dedicatòria Als meus pares, pel vostre sacrifici i paciència. Gràcies per lluitar per mi i recolzar-me sempre. A en Gil, pel teu suport al llarg de tot el grau. No deixis mai de somriure. A la Irene, per inspirar-me. A en Guillem i la Berta. Agraïments A en Xavi, de nou, quatre anys més tard, per la teva paciència i per compartir amb mi la teva passió. A en Ferran i la Irene, per cedir-me una part del vostre art. A tots els qui heu fet possible aquest projecte. Resum Aquest projecte es basa en estudiar com afecta la presència o absència del so a les produccions audiovisuals analitzant la diferència entre el visionat d’un curtmetratge de cinema mut i el mateix curtmetratge després de ser sonoritzat. Per a dur a terme aquesta investigació, s’ha realitzat un procés complet de sonorització i postproducció sonora del curtmetratge The Electric House (Buster Keaton, 1922). Resumen Este proyecto se basa en estudiar cómo afecta la presencia o absència de sonido en las producciones audiovisuales analizando la diferencia entre el visionado de un cortometraje de cine mudo y el mismo cortometraje después de haber sido sonorizado. Para llevar a cabo esta investigación, se ha realizado un proceso completo de sonorización y postproducción sonora del cortometraje The Electric House (Buster Keaton, 1922). Abstract This project is based in studying how the presence or absence of sound influences an audiovisual production by analyzing the difference between the view of a silent short film and the same production after a process of sound post production.