A Carpet Page in the Book of Durrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Medieval Europe

Early Medieval Europe 1 Early Medieval Sites in Europe 2 Figure 16-2 Pair of Merovingian looped fibulae, from Jouy-le-Comte, France, mid-sixth century. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones, 4” high. Musée d’Archéologie nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye. 3 Heraldic Motifs Figure 16-3 Purse cover, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial in Suffolk, England, ca. 625. Gold, glass, and cloisonné garnets, 7 1/2” long. British Museum, London. 4 5 Figure 16-4 Animal-head post, from the Viking ship burial, Oseberg, Norway, ca. 825. Wood, head 5” high. University Museum of National Antiquities, Oslo. 6 Figure 16-5 Wooden portal of the stave church at Urnes, Norway, ca. 1050–1070. 7 Figure 16-6 Man (symbol of Saint Matthew), folio 21 verso of the Book of Durrow, possibly from Iona, Scotland, ca. 660–680. Ink and tempera on parchment, 9 5/8” X 6 1/8”. Trinity College Library, Dublin. 8 Figure 16-1 Cross-inscribed carpet page, folio 26 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 9 Figure 16-7 Saint Matthew, folio 25 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 10 Figure 16-8 Chi-rho-iota (XPI) page, folio 34 recto of the Book of Kells, probably from Iona, Scotland, late eighth or early ninth century. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1” X 9 1/2”. -

The Date and Context of the Glamis, Angus, Carved Pictish Stones Lloyd Laing*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 131 (2001), 223–239 The date and context of the Glamis, Angus, carved Pictish stones Lloyd Laing* ABSTRACT The widely accepted eighth-century dating for the Pictish relief-decorated cross-slabs known as Glamis 2 and Glamis 1 is reviewed, and an alternative ninth-century date advanced for both monuments. It is suggested that the carving on front and back of Glamis 2 was contemporaneous, and that both monuments belong to the Aberlemno School. GLAMIS 2 DESCRIPTION The Glamis 2 stone (Allen & Anderson’s scheme, 1903, pt III, 3–4) stands in front of the manse at Glamis, Angus, and its measurements — 2.76 m by 1.5 m by 0.24 m — make it one of the larger Class II slabs. It is probably a re-used Bronze Age standing stone as there appear to be some cup- marks incised on the base of the cross face. Holes have been drilled in the relatively recent past at the base of the sides, presumably for support struts. Viewed from the front (cross) face the slab is pedimented, the ornament being partly incised, partly in relief (illus 1). The cross is in shallow relief, has double hollow armpits and a ring delimited by incised double lines except in the bottom right hand corner, where the ring is absent. It is decorated with interlace, with a central interlaced roundel on the crossing. The interlace on the cross-arms and immediately above the roundel is zoomorphic. At the top of the pediment is a pair of beast heads, now very weathered, with what may be a human head between them, in low relief. -

Gothic Architecture the Gothic Period Began with the Construction of the Choir at St

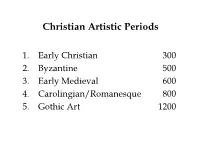

Christian Artistic Periods 1. Early Christian 300 2. Byzantine 500 3. Early Medieval 600 4. Carolingian/Romanesque 800 5. Gothic Art 1200 The Good Shepherd in the Catacomb of Saints Pietro and Marcellino, Rome (E. Christian, early 4th century CE). Edicule, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem Saint Apollinaire as the Good Shepherd, Early Christian, mosaic, St. Apollinaire in Classe, Ravenna, Italy. Christ the Good Shepherd, mosaic, Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna Terminology • Catacomb • Fresco • Basilica • Longitudinal plan • Facade • Central plan • Atrium • Latin Cross Plan • Narthex • Mosiacs • Nave • Altar • Apse • Transept Justinian and Attendants (Byzantine, c. 547 CE). Mosaic. San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy Anthemius and Isidorus. Hagia Sophia, (Byzantine, 532-537 CE) Istanbul, Turkey. Pantocrator, Byzantine, mosaic, Hagia Sophia Madonna Enthroned tempera and gold leaf on panel, Byzantine, 1300 ce Early Christian and Byzantine Themes and Concepts: • basilica versus central plan • West versus East • church and state • Mosaics, tempera, and gold-leaf • icon, iconography Purse Cover from Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, Suffolk, England, before 655, gold and enamel, 7.5 ‘ long Animal-Head Post from Oseberg Ship Burial, Maritime Museum in Stockholm, Sweden, c. 825, wood The High Cross of Muiredach, west face, gets its name from an inscription at the base of the west face, saying it was erected by Muiredach. 10th or possibly 9th century, located at the ruined monastic site of Monasterboice, in County Louth, Ireland. Irish high crosses are internationally recognized icons of early medieval Ireland. c. 850, sandstone, 19’ The Lindisfarne Gospels is a manuscript that contains the Gospels of the four Evangelists Mark, John, Luke, and Matthew. -

A Reassessment of the Early Medieval Stone Crosses and Related Sculpture of O Aly, Kilkenny and Tipperary

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early medieval stone crosses and related sculpture of oaly, Kilkenny and Tipperary Edwards, Nancy How to cite: Edwards, Nancy (1982) A reassessment of the early medieval stone crosses and related sculpture of oaly, Kilkenny and Tipperary, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7418/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 a Reassessment op tbe ecmly raeofeoat stone cRosses ariO ReLateo scaLptciRe of offaly kilkenny ano tfppeRciR^y nancy efocoa&os Abstract This study is concerned with the Early Medieval freestanding stone crosses and related sculpture of three Irish counties, Offaly, Kilkenny and Tipperary. These monuments are recorded both descriptively and photographically and particular emphasis has been placed on a detailed analysis of the Hiberno-Saxon abstract ornament, the patterns used and, where possible, the way in which they were constructed. -

WOVEN WORDS in the LINDISFARNE GOSPELS By

WOVEN WORDS IN THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS by Chiara Valle A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland July, 2015 Abstract This dissertation investigates the meanings and function of the five ornamental pages that decorate the Lindisfarne Gospels (London, British Library, Cotton Nero D.IV), a Gospel book produced in the British Isles, most likely in the Isle of Lindisfarne, around 720 CE. Along with the ornament, the manuscript is embellished with portraits of the Evangelists and display scripts. Since the publication of a facsimile edition in 1960, the manuscript has been widely studied. A vast bibliography has explored the meanings of the miniatures, analyzing the ornament within the early medieval pictorial tradition of the Mediterranean basin. The present research relies on these studies, and takes a slightly different perspective by examining the ways that the ornamental pages work within the book itself. Interpreting each carpet page in light of the preceding portrait and the following text, it explores the ways in which the written and figurative languages share means of construction with the ornamental pages and enhance their metamorphic nature. The carpet pages transform the geometric shapes into crosses, they blur the positive and the negative spaces, they reveal and hide crosses and geometric shapes. This dissertation interprets the ornament not so much as a static image, but rather as a composition in motion that exists in tension between figurative and abstract, between mimicked materials and pure signs. The fluid and transformative character of the carpet pages prompts the beholder to assume an interpretative role, discerning new patterns and shapes each time he looks at the ornament. -

Navigation, Search a Carpet Page from the Lindisfarne Gospels Carpet

Carpet page From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A carpet page from the Lindisfarne Gospels Carpet pages are a characteristic feature of Insular illuminated manuscripts. They are pages of mainly geometrical ornamentation, which may include repeated animal forms, typically placed at the beginning of each of the four Gospels in Gospel Books. The designation "carpet page" is used to describe those pages in Christian, Islamic, or Jewish illuminated manuscripts that contain little or no text and which are filled entirely with decorative motifs.[1][2][3] They are distinct from pages devoted to highly decorated historiated initials, though the style of decoration may be very similar.[4] Carpet pages are wholly devoted to ornamentation with brilliant colors, active lines, and complex patterns of interlace. They are normally symmetrical, or very nearly so, about both a horizontal and vertical axis, though for example the page at right is only symmetrical about a vertical axis. Some art historians find their origin in similar Coptic decorative book pages,[5] and they also clearly borrow from contemporary metalwork decoration. Oriental carpets, or other textiles, may themselves have been influences. The tooled leather book binding of the St Cuthbert Gospel represents a simple carpet page in another medium,[6] and the few surviving treasure bindings - metalwork book covers or book shrines - from the same period, such as that on the Lindau Gospels, are also close parallels.[7] Roman floor mosaics seen in post-Roman Britain, are also cited as a possible source.[8] The Hebrew Codex Cairensis, from 9th century Galilee, also contains a similar type of page, but stylistically very different. -

Early Christian Art in Ireland Kindle

EARLY CHRISTIAN ART IN IRELAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Margaret Stokes | 242 pages | 01 Sep 2015 | Palala Press | 9781340862695 | English | none Early Christian Art in Ireland PDF Book Sign up here to see what happened On This Day , every day in your inbox! The beginnings of Early Christian art date to the period when the religion was yet a modest and sometimes persecuted sect, and its flowering was possible only after , when the Christian emperor Constantine the Great decreed official toleration of Christianity. Like in the Cathach, dots are also used to decoate the letter,but now the whole letter is outlined with dots. Their strong point was the creation of tiny sculptures, particularly for the embossed engraving of coinage - for which, see Celtic Coin art. Meath and by the door ornaments from Donore, Co. These were Latin texts of the gospels and psalms. Triskeles, spirals and hatching decorate the angels' wings and the outer robes of the two figures below. The mission of Aidan of Iona in the s to the ancient kingdom of Northumbria in northern England was especially important in the later development of insular Celtic art. Proceed to Basket. Another thing: losing my religion - a cross from the Parthenon. It was found near Ardagh, Co Limerick in the 19th century by a boy digging potatoes. Stokes Press. Columba One of the earliest Irish illuminated manuscripts , and a treasure of early Christian art , the Cathach of St. All rights reserved. Ornament was dominated by trumpet scrolls, fine spirals often designed to be seen as a reserved line of metal in a field of red enamel and this motif is best exemplified on the escutcheens of a series of vessels called "hanging bowls". -

Origins and Interpretations of Folio 3V in the Book of Durrow

Issue 4 2014 Being and Becoming: Origins and Interpretations of Folio 3v in the Book of Durrow CLAIRE DILLON NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY As the oldest extant insular illuminated manuscript, the Book of Durrow is a significant codex that embodies the cultural blending that occurred as Christianity adapted to the cultures of Britain and Ireland. Much of the knowledge regarding this manuscript, created in Ireland around the second half of the seventh century, has been lost to history. Folio 3v is particularly enigmatic, as it has been dislocated and decontextualized throughout the centuries. However, this isolation liberates folio 3v from its nebulous history and places it in an ongoing dialogue with a multiplicity of interpretations. This multiplicity is perhaps the appeal of insular illumination, as this ornamentation bridged the visual cultures of Christians and potential converts. Folio 3v features a spiral motif, which is unique to this page and is key to understanding it. “Being and becoming” refers to both the spiral’s static form and the sense of movement that this form evokes, representing the contrast between its Christian origins and its openness to interpretation. By representing the intersections of pagan and Christian spirituality, the spiral recalls notions of transcendence, universality, and intermediation, which likely resonated with medieval viewers of diverse religions, just as they now speak to contemporary viewers across centuries. I. Introduction But if you have found customs, whether in the Church of Rome or of Gaul or any other that may be more acceptable to God, I wish you to make a careful selection of them, and teach the Church of the English, which is still young in the Faith, whatever you have been able to learn with profit from the various Churches. -

KEY CONCEPTS for the EARLY MEDIEVAL PERIOD

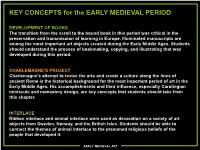

KEY CONCEPTS for the EARLY MEDIEVAL PERIOD DEVELOPMENT OF BOOKS The transition from the scroll to the bound book in this period was critical in the preservation and transmission of learning in Europe. Illuminated manuscripts are among the most important art objects created during the Early Middle Ages. Students should understand the process of bookmaking, copying, and illustrating that was developed during this period. CHARLEMAGNE'S PROJECT Charlemagne's attempt to revive the arts and create a culture along the lines of ancient Rome is the historical background for the most important period of art in the Early Middle Ages. His accomplishments and their influence, especially Carolingian miniscule and monastery design, are key concepts that students should take from this chapter. INTERLACE Ribbon interlace and animal interlace were used as decoration on a variety of art objects from Sweden, Norway, and the British Isles. Students should be able to connect the themes of animal interlace to the presumed religious beliefs of the people that developed it. EARLY MEDIEVAL ART Three Basic parts to Early Medieval Era: Fall of Western Empire 400-600 Art of the Warlords: The PAGAN Years Western Empire now broken up amongst the Goths, Angles, Saxons and Franks… Known for the ‘animal style’ that is prevalent in this period… Chi Rho Iota from the Book of Kells 700-800 HIBERNO-SAXON ART: Produced in Ireland (Hiberno) and England (Saxon). Much like the Pagan art (interwoven designs), but contained Christian concepts. CAROLINGIAN Period (768-814): Charlemagne crowned King of the Franks and Christian Ruler in 768… Cathedral of Aachen promoted the ‘three-part elevation’ to Churches… Education to the people through art and illuminated manuscripts, like the Ebbo Gospels OTTONIAN Periods (950-1050): The Three German Ottos known for uniting the region under a common Christian Rule again, which sparks the need for bigger churches in the ROMANESQUE period. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 12:32:03PM Via Free Access 140

139 4 Assembling and reshaping Christianity in the Lives of St Cuthbert and Lindisfarne Gospels In the previous chapter on the Franks Casket, I started to think about the way in which a thing might act as an assembly, gather- ing diverse elements into a distinct whole, and argued that organic whalebone plays an ongoing role, across time, in this assemblage. This chapter begins by moving the focus from an animal body (the whale) to a human (saintly) body. While saints, in early medieval Christian thought, might be understood as special and powerful kinds of human being – closer to God and his angels in the heavenly hierarchy and capable of interceding between the divine kingdom and the fallen world of mankind – they were certainly not abstract otherworldly spirits. Saints were embodied beings, both in life and after death, when they remained physically present and accessible through their relics, whether a bone, a lock of hair, a fingernail, textiles, a preaching cross, a comb, a shoe. As such, their miracu- lous healing powers could be received by ordinary men, women and children by sight, sound, touch, even smell or taste. Given that they did not simply exist ‘up there’ in heaven but maintained an embodied presence on earth, early medieval saints came to be asso- ciated with very particular places, peoples and landscapes, with built and natural environments, with certain body parts, materi- als, artefacts, sometimes animals. Of the earliest English saints, St Cuthbert is probably one of, if not the, best known and even today remains inextricably linked to the north-east of the country, especially the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and its flora and fauna. -

Early Medieval Europe Flashcards

Early Medieval Europe Flashcards 1 Figure 16-3 Purse cover, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial in Suffolk, England, ca. 625. Gold, glass, and cloisonné garnets, 7 1/2” long. British Museum, London. 2 Figure 16-4 Animal-head post, from the Viking ship burial, Oseberg, Norway, ca. 825. Wood, head 5” high. University Museum of National Antiquities, Oslo. 3 Figure 16-5 Wooden portal of the stave church at Urnes, Norway, ca. 1050–1070. 4 Figure 16-1 Cross-inscribed carpet page, folio 26 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 5 Figure 16-8 Chi-rho-iota (XPI) page, folio 34 recto of the Book of Kells, probably from Iona, Scotland, late eighth or early ninth century. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1” X 9 1/2”. Trinity College Library, Dublin. 6 Figure 16-9 High Cross of Muiredach (east face), Monasterboice, Ireland, 923. Sandstone, 18’ high. 7 Figure 16-12 Equestrian portrait of Charlemagne or Charles the Bald, from Metz, France, ninth century. Bronze, originally gilt, 9 1/2” high. Louvre, Paris. 8 Figure 16-13 Saint Matthew, folio 15 recto of the Coronation Gospels (Gospel Book of Charlemagne), from Aachen, Germany, ca. 800– 810. Ink and tempera on vellum, 1’ 3/4” X 10”. Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. 9 Figure 16-14 Saint Matthew, folio 18 verso of the Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of Archbishop Ebbo of Reims), from Hautvillers (near Reims), France, ca. 816–835. Ink and tempera on vellum, 10 1/4” X 8 3/4”. -

Sutton Hoo Is the Site of Two Anglo- Saxon Cemeteries of the 6Th and Early 7Th Centuries, One of Which Contained an Undisturbed Ship Burial, Possibly of King Raedwald

Europe After the Fall of Rome: Early Medieval Art in the West 5th – 10th c. Map of Germanic Migrations, 4th – 6th c. Early Medieval Sites in Europe Art of the Warrior Lords 5th-10th c. The surviving art of the non-Roman peoples that competed for power after the fall of Rome consists of small-scale status symbols, especially portable items of personal adornment. They frequently combined animal forms and interlace pattern. Merovingian looped fibulae (The Merovingians were a dynasty of Frankish kings), from Jouy-le- Comte, France, mid sixth century. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones, 4” long. Musée des Antiquités Nationales, Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Comparison: Fibula with Orientalizing lions from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb, Cerveteri, Italy, ca. 650–640 BCE. Gold, approx. 1’ 1/2” high. Merovingian looped fibulas, from Jouy-le- Comte, France, mid sixth century. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones, 4” long. Comparison: Justinian, Bishop Maximianus, and attendants, mosaic from San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, ca. 547. Sutton Hoo is the site of two Anglo- Saxon cemeteries of the 6th and early 7th centuries, one of which contained an undisturbed ship burial, possibly of King Raedwald. A ghost image of the buried ship was revealed during excavations in 1939 Sutton Hoo ceremonial helmet http://youtu.be/np0pD1wW_Bo Cloisonné:. In making cloisonné enamels the surface to be decorated is divided into compartments with strips of metal (cloisons); the compartments are then filled with enamel (glass in either powder or paste form) and the whole piece is fired in a kiln.