The Struggle to Make Sacred Places in the Secular Space of Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sherman Oaks-Studio City-Toluca Lake-Cahuenga Pass Activity Log

SHERMAN OAKS-STUDIO CITY- TOLUCA LAKE-CAHUENGA PASS Community Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACTIVITY LOG COMMUNITY MAPS COMMUNITY PLAN I. Introduction II. Function of the Community Plan III. Land Use Policies and Programs IV. Coordination Opportunities for Public Agencies V. Urban Design www.lacity.org/PLN (General Plans) A Part of the General Plans - City of Los Angeles SHERMAN OAKS-STUDIO CITY-TOLUCA LAKE-CAHUENGA PASS ACTIVITY LOG ADOPTION DATE PLAN CPC FILE NO. COUNCIL FILE NO. May 13, 1998 Sherman Oaks-Studio City-Toluca Lake-Cahuenga 95-0356 CPU 97-0704 Pass Community Plan Update Jan. 4, 1991 Ventura-Cahuenga Boulevard Corridor Specific Plan 85-0383 85-0926 S22 May 13, 1992 Mulholland Scenic Parkway Specific Plan 84-0323 SP 86-0945 ADOPTION DATE AMENDMENT CPC FI LE NO. COUNCIL FIL E Sept. 7, 2016 Mobility Plan 2035 Update CPC-2013-910-GPA-SPCA-MSC 15-0719 SHERMAN OAKS-STUDIO CITY- TOLUCA LAKE-CAHUENGA PASS Community Plan Chapter I INTRODUCTION COMMUNITY BACKGROUND PLAN AREA The Sherman Oaks-Studio City-Toluca Lake-Cahuenga Pass Community Plan area is located approximately 8 miles west of downtown Los Angeles, is bounded by the communities of North Hollywood, Van Nuys-North Sherman Oaks on the north, Hollywood, Universal City and a portion of the City of Burbank on the east, Encino-Tarzana on the west and Beverly Crest-Bel Air to the south. The area is comprised of five community subareas, each with its own identity, described as follows: • Cahuenga Pass is the historical transition from the highly urbanized core of the city to the rural settings identified with the San Fernando Valley. -

Specific Plan

VENTURA-CAHUENGA BOULEVARD CORRIDOR Specific Plan Ordinance No. 166,560 Effective February 16, 1991 Amended by Ordinance No. 171,240 Effective September 25, 1996 Amended by Ordinance No. 174,052 Effective August 18, 2001 Specific Plan Procedures Amended by Ordinance No. 173,455 TABLE OF CONTENTS MAPS Specific Plan Area Section 1. Establishment of Specific Plan Section 2. Purposes Section 3. Relationship to Other Provisions of the Los Angeles Municipal Code Section 4. Definitions Section 5. Prohibitions, Violations, Enforcement, Use Limitations and Restrictions, and Exemptions Section 6. Building Limitations Section 7. Land Use Regulations Section 8. Sign Regulations Section 9. Project Permit Compliance Section 10. Transportation Mitigation Standards and Procedures Section 11. Project Impact Assessment Fee Section 12. PIA Fee-Funded Improvements and Services Section 13. Prior Projects Permitted Section 14. Public Right-Of-Way Improvements Section 15. Plan Review Section 16. Alley Vacations Section 17. Owners Acknowledgment of Limitations Section 18. Severability Section 19. Specific Plan Exceptions Exemption Section 20. Repeal of Existing Ventura/Cahuenga Corridor Specific Plan Ordinance A Part of the General Plan - City of Los Angeles www.lacity.org/Pln (General Plans) Ventura/Cahuenga Boulevard Corridor Specific Plan Exhibits A-G Tarzana Section A Corbin Av B Reseda Bl Tampa Av Wilbur Av Winnetka Av Lindley Av Topanga Canyon Bl Burbank Bl Shoup Av Canoga Av Sherman Oaks Section De Soto Av Fallbrook Av Zelzah Av White Oak Av C Louise Av -

L a County Sheriff Jim Mcdonnell Public Safety Challenges for 2018: *Crime *Counter-Terrorism *Mental Illness *Opioids *Recruitment of Officers

L A County Sheriff Jim McDonnell Public Safety Challenges for 2018: *Crime *Counter-Terrorism *Mental Illness *Opioids *Recruitment of Officers COMMUNITY MEETING WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2017 - 7:15 PM NOTRE DAME HIGH SCHOOL • RIVERSIDE & WOODMAN, SHERMAN OAKS Los Angeles County Sheriff Jim McDonnell will be our guest speaker on Wednesday evening October 18, 2017. Many of us are very familiar with Sheriff McDonnell because he has spoken at previous Meetings as the second in command to Los Angeles Police Chief William Bratton. In 2010, he left the Los Angeles Police Department to become Chief of Police in the City of Long Beach. In 2014, he was elected as Los Angeles County Sheriff. Chief McDonnell brings decades of experience and expertise to the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. He is well-respected within the community and among law enforcement agencies. McDonnell has served as President of the Los Angeles County Police Chiefs’ Association as well as California Peace Officers’ Association. He is committed to keeping our streets safe while being transparent and proactively addressing the root causes of all crimes. Learn how Chief McDonnell deals with the challenges of overseeing 18,000 employees and what is being done to solve admitted problems within the Sheriff’s Department. Chief McDonnell will also discuss the controversy over the Sheriff’s Department’s use of drones. He will explain how the Sheriff’s Department is prepared if a Las Vegas shooting were to occur in Los Angeles. How will immigration rules from Washington, D.C. impact policing in our communities? Jules Feir announces that Poquito Mas will be our Restaurant of the Month. -

Support Docs 7D 06/15/2017

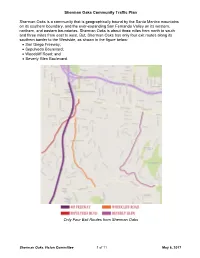

Sherman Oaks Community Traffic Plan Sherman Oaks is a community that is geographically bound by the Santa Monica mountains on its southern boundary, and the ever-expanding San Fernando Valley on its western, northern, and eastern boundaries. Sherman Oaks is about three miles from north to south and three miles from east to west. But, Sherman Oaks has only four exit routes along its southern border to the Westside, as shown in the figure below: • San Diego Freeway; • Sepulveda Boulevard; • Woodcliff Road; and • Beverly Glen Boulevard. Only Four Exit Routes from Sherman Oaks Sherman Oaks Vision Committee 1 of 11 May 6, 2017 Sherman Oaks Community Traffic Plan Sherman Oaks was first developed in 1927 with only three canyon exit routes to the Westside – the San Diego Freeway did not exist until 1964. This lack of viable exits created a huge future problem because there are so many job opportunities on the Westside. Years ago, traffic flowing through Sherman Oaks was manageable. But, with increasing population growth more people from across the Valley started using these canyon routes to access their jobs and schools on the Westside – thus straining the capacity of these routes. As traffic became heavier, it began to overflow onto secondary streets. This caused many neighborhoods such distress that the city began limiting access to these secondary streets through turn restrictions during peak travel times. This further concentrated traffic onto already overcrowded canyon routes, many of which are substandard streets, causing gridlock. Throughout Sherman Oaks, much of our troubles stem from streets never intended for heavy traffic. -

Los Angeles City Planning Department

JOHN O’HARA TOWNHOUSE 10733-10735 ½ Ohio Avenue CHC-2015-1979-HCM ENV-2015-2185-CE Agenda packet includes 1. Final Staff Recommendation Report 2. Categorical Exemption 3. Letter from John O’Hara’s daughter, Lylie O’Hara Doughty 4. Under Consideration Staff Recommendation Report 5. Nomination Please click on each document to be directly taken to the corresponding page of the PDF. Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-1979-HCM ENV-2015-2185-CE HEARING DATE: August 6, 2015 Location: 10733-10735 ½ Ohio Avenue TIME: 9:00 AM Council District: 5 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Westwood 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: West Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Westwood 90012 Legal Description: TR 7803, Block 28, Lot 14 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the JOHN O’HARA TOWNHOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Thomas Berry 986 La Mesa Terrace Unit A Sunnyvale, CA 94086 Caribeth LLC c/o John Ketcham 626 Adelaide Drive Santa Monica,CA 90402 APPLICANT: Marlene McCampbell 10634 Holman Ave. Apt 1 Los Angeles, CA 90024 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the subject property a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7. 2. Adopt the staff report and findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager -

3406. Mediterranean Fruit Fly Interior Quarantine a Quarantine Is

3406. Mediterranean Fruit Fly Interior Quarantine A quarantine is established against the following pest, its hosts, and possible carriers: (a) Pest. Mediterranean fruit fly (Continued) (b) Quarantine Area. The area under quarantine for Mediterranean fruit fly in California is: (1) In the Santa Monica area of Los Angeles County: Beginning at the intersection of Stoney Hill Road and Mt St. Marys Fire Road; then, southeasterly on Mt. St. Marys Fire Road to its intersection with an unnamed road at 34.098629 latitude and -118.487062 longitude; then, starting northeasterly along the unnamed road to its intersection with Promontory Road; then, starting southwesterly along Promontory Road to its intersection with N Sepulveda Boulevard; then, starting southeasterly along N Sepulveda Boulevard to its intersection with US Interstate 405; then, easterly along an imaginary line to the westernmost point of Savona Road; then, starting easterly along Savona Road to its intersection with Stradella Road; then, starting southerly along Stradella Road to its intersection with Portofino Place; then, northeasterly along an imaginary line to the intersection of Levico Way and Stone Canyon Road; then, starting southeasterly along Stone Canyon Road to its intersection with Vestone Way; then, starting northeasterly along Vestone Way to its intersection with Bel Air Road; then, starting southeasterly along Bel Air Road to its intersection with Sandall Lane; then, southeasterly along Sandall Lane to its easternmost point; then, northeasterly along an imaginary line -

Traffic, Circulation, and Parking

4.1 Traffic, Circulation, and Parking This section describes the existing transportation and parking conditions within and adjacent to the project area. A traffic report describing the potential impacts of the proposed project was prepared by Iteris in March 2010 and is included as Appendix B. This section summarizes the findings of the traffic report and discusses any necessary mitigation and residual impacts after mitigation. The study area for the traffic report prepared for the proposed project was developed in conjunction with LACMTA and the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT). A study area that included 74 study intersections, consisting of intersections along Wilshire Boulevard, as well as parallel corridors, such as Sunset Boulevard, Santa Monica Boulevard, Olympic Boulevard, Pico Boulevard, 3rd Street, 6th Street, and 8th Street, was established for the proposed project. 4.1.1 Environmental Setting The following discussion includes an overview of the transportation system within the Wilshire BRT study area. The roadway system in the study area forms a grid pattern, with arterials and collectors that generally follow a northeast-to-southwest orientation in the western portion of the study area (west of the City of Beverly Hills) and an east-to-west orientation in the eastern portion of the study area (east of the City of Beverly Hills.) Freeway Network The Santa Monica Freeway (Interstate 10 [I-10]) is a major east-west freeway that parallels Wilshire Boulevard south of the study area. The freeway is one of the busiest and carries some of the highest daily traffic volumes in the nation. Annual counts from the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) indicate that the 2007 average daily traffic (ADT) on I-10 ranges from 199,000 (east of Centinela Avenue) to 323,000 (east of Vermont Avenue). -

1985 I405corridorstudy Techm

IOUTHERR CALIfOAnlA ADOCIATIOn Of GOVERnmEnTJ 600 fouth Commonweolth Avenue. fuite 1000 • Lol' Angelel' • CoHfornio • 90005 • 2!3/385-1000 I-405 CORRIDOR STUDY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM #2 EXISTI~G CONDITIONS AND NEEDS ANALYSIS DRAFT P-n:pared by: Special Projects Section Oepdrtment of Transportation Planning Southern California Association of Governments 600 South Commonwealth Avenue Los Angeles, California 90005 October, 1985 IOUTHERn CALIfORniA AI/oeIATlOn OF GOVERnmenTI 600 louth Commonwealth Avenue ./uite 1000 • lol' Angelel'. CaU'omio • 90005 • 213/385-1000 I-405 CORRIDOR STUDY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM #2 EXISTING CONDITIONS AND NEEDS ANALYSIS DRAFT Prepared by: Special Projects Section Department of Transportation Planning Southern California Association of Governments 600 South Commonwealth Avenue los Angeles, California 90005 October. 1985 MTA L ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared, by the following people: William R. Wells Special Projects Manager Peter Samuel Behrman Joan Jenkins TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary v I. Study Area Definition 1 II. Existing Demographic Conditions 3 III. Existing Land Use Conditions 3 IV. Existing Transportation System Conditions 3 A. LARTS Mode 1 Data 3 B. Freew~s 3 1. 1-405 3 2. Route 90 10 3. 1-10 10 C. Arterials 14 1. Sepulveda Boulevard 14 2. Bundy Drive-Centinela Avenue 18 3. Jefferson Boulevard-Overland Avenue-Westwood Boulevard- Beverly Glen Boulevard 19 D. Pub 1i c Transportat; on 26 1. Publicly Owned Systems 26 2. Privately Owned Systems 39 3. 1984 Transit Conclusions 40 V. Year 2000/2010 Forecasts 40 A. Freew~s 40 1. I-405 40 2. Route 90 41 3. 1-10 41 B. Arterials 42 1. -

Board of Neighborhood Commissioners Take the Following Action on This Request

200 N. Spring Street, 20th FL, Los Angeles, CA 90012 • (213) 978-1551 or Toll-Free 3-1-1 E-mail: [email protected] www.EmpowerLA.org The Department of Neighborhood Empowerment recommends the Board of Neighborhood Commissioners take the following action on this request: Adopt Requested Change(s) to Board Structure Reject Requested Change(s) to Board Structure. The Department acknowledges the Westside Neighborhood Council’s (WNC) past outreach efforts and concurs with the WNC reasoning to change their Board structure, increasing their total Board size from 17 to 19 members by: 1. Adding 1 new Business Seat (Seat 19), and 2. Adding 1 new Residential Seat (Seat 18) WNC’s reasoning was that the original areas for Business Seats 1 & 2 as well as Residential Seat 7 were too large for adequate coverage and representation. The WNC Board aims to increase one additional seat for each of these specific areas within their boundaries. They aim to ensure that the represented area within the neighborhood is the best reflection of the diverse stakeholders' within WNC. In order to see what would warrant an increase in the Board Seat, there had to be a review of the affected area(s) and the use of a uniform guide for retrieving data for this Neighborhood Council. The use of the Census Tracts (2671, 2672, 2678, & 2679.02) in combination with the use of the American Community Survey (ACS) Demographic and Housing Estimates & Selected Housing Characteristics Survey were resources that helped guide the reasoning for the finding. According to the ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates Survey (DP05) of 2017 through 2014, within the four (4) Census Tract Numbers (2671, 2672, 2678, & 2679.02), the growth of the Sex and Age: Total Populations between 2014 and 2017 grew an estimated total of 1,308. -

Building, Utility and Adjacent Structure Protection – Tunnels (Final) Task No

LOS ANGELES COUNTY METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY WESTSIDE PURPLE LINE EXTENSION PROJECT, SECTION 3 ADVANCED PRELIMINARY ENGINEERING Contract No. PS‐4350‐2000 Building, Utility and Adjacent Structure Protection – Tunnels (Final) Task No. 58.03.110.03B Prepared for: Prepared by: 777 South Figueroa Street, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90017 September 2017 Building, Utility and Adjacent Structure Protection – Tunnels (Final) Table of Contents Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1‐1 1.1 Building and Utility Protection Program .......................................................................... 1‐1 1.2 Allowable Criteria for Building and Major Utility Settlement .......................................... 1‐1 1.3 Building and Utility Protection Program Approach ......................................................... 1‐2 1.4 Purpose of the Building and Utility Protection Program Report ‐ Tunnels ..................... 1‐2 1.5 Background ...................................................................................................................... 1‐3 2.0 ALIGNMENT AND GEOLOGY .................................................................................................. 2‐1 2.1 Project Alignment ............................................................................................................ 2‐1 2.2 Project Geology ............................................................................................................... -

Iv. Environmental Impact Analysis I. Noise

IV. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS I. NOISE 1. INTRODUCTION This section analyzes potential noise and vibration impacts associated with construction and operation of the proposed project. The analysis describes the existing noise environment within the vicinity of the project site, estimates future noise levels at surrounding land uses resulting from construction and operation of the proposed project, identifies the potential for significant impacts, and provides mitigation measures to address significant impacts. In addition, an evaluation of the potential cumulative noise impacts from the proposed project and known related projects is also provided. Noise calculation worksheets are included in Appendix G of this Draft EIR. 2. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING a. Noise and Vibration Basics (1) Noise Noise is most often defined as unwanted sound. Although sound can be easily measured, the perceptibility of sound is subjective and the physical response to sound complicates the analysis of its impact on people. People judge the relative magnitude of sound sensation in subjective terms such as “noisiness” or “loudness.” Sound pressure magnitude is measured and quantified using a logarithmic ratio of pressures, the scale of which gives the level of sound in decibels (dB). The human hearing system is not equally sensitive to sound at all frequencies. Therefore, to approximate this human, frequency‐dependent response, the A‐weighted filter system is used to adjust measured sound levels. The A‐weighted sound level is expressed in “dBA.” This scale de‐emphasizes low frequencies to which human hearing is less sensitive and focuses on mid‐ to high‐range frequencies. Although the A‐weighted scale accounts for the range of people’s response, and therefore, is commonly used to quantify individual event or general community sound levels, the degree of annoyance or other response effects also depends on several other perceptibility factors. -

Los Angeles City Guide: How to Prepare for a Successful Summer in Los Angeles, CA the Resources in This Guide Are for Informational Purposes Only

Career Advancement Los Angeles City Guide: How to Prepare for a Successful Summer in Los Angeles, CA The resources in this guide are for informational purposes only. Career Advancement does not endorse or guarantee any of the services described in this document. Students should exercise their own discretion when planning for their summer internship. If you would like more information or have questions about this document, feel free to speak with a Career Advancement adviser. You can make an appointment on UChicago Handshake. 4. Politely ask your employer about housing resources. Your L.A. Housing Overview employer may have suggestions for where to live, or give Whether you are craving some relaxation at the beach, you the contact information of other interns who are spending time outdoors, or checking out the culture and searching for housing so that you can room together or get cuisine, L.A. has it all! advice from each other. L.A. has been a popular location for summer internships and Online Housing Resources provides a great opportunity to explore what it is like to live in There are a variety of online housing resources that provide a different city. The type of housing you’re looking for, your short-term housing vacancies, including: budget, and your connections in L.A. are all factors that should help determine where you begin your housing search. http://losangeles.craigslist.org/ The earlier you begin looking, the more options you will have https://www.airbnb.com/s/Los-Angeles--CA and the easier it will be to choose exactly where you want to http://losangeles.apartments.com/ live for the summer.