The Filibusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Mcguffey's Sixth Eclectic Reader by William Holmes Mcguffey

The Project Gutenberg EBook of McGuffey's Sixth Eclectic Reader by William Holmes McGuffey This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: McGuffey's Sixth Eclectic Reader Author: William Holmes McGuffey Release Date: September 26, 2005 [EBook #16751] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MCGUFFEY'S SIXTH ECLECTIC READER *** Produced by Don Kostuch [Transcriber's Notes: Welcome to the schoolroom of 1900. The moral tone is plain. "She is kind to the old blind man." The exercises are still suitable, and perhaps more helpful than some contemporary alternatives. Much is left to the teacher. Explanations given in the text are enough to get started teaching a child to read and write. Counting in Roman numerals is included as a bonus in the form of lesson numbers. The form of contractions includes a space. The contemporary word "don't" was rendered as "do n't". The author, not listed in the te xt, is William Holmes McGuffey. Passages using non-ASCI characters are approximately rendered in the text version. The DOC and PDF versions include the original images. The section numbers are decimal in the Table of Contents but are in Roman Numerals in the body. Don Kostuch end transcriber's notes] She sits, inclining forward as to speak, Her lips half-open, and her finger up, As though she said, "Beware!" (Page 341) ECLECTIC EDUCATIONAL SERIES. -

Period 06 Final Exam

Period Six Final Exam Taming of the Shrew Baptista Bianca Biondello Gremio Grumio Hortensio Katherine Lucentio Merchant Petruchio Tranio 1. Who said, “Tranio, since for the great desire I had To see fair Padua, nursery of arts. I am arrived for Fruitful Lombardy. The pleasant garden of great Italy. And by my father’s love and leave am armed with his goodwill and good company.” 2. Who said, “Gentlemen, importune me no farther, For how I firmly am resolved you know – That is not to bestow my youngest daughter Before I have a husband for the elder.” 3. Who said, “Sister, content you in my discontent – Sir. To your pleasure humbly I subscribe. My books and instruments shall be my company. On them to look and practice by myself.” 4. Who said, “Where have I been? Nay, how now, where are you? Master, has my fellow Tranio stolen your clothes? Or you stolen his? Or both? Pray what’s the news? 5. Who said, “How now, what’s the matter? My old friend Grumio and my good friend Petruchio? How do you all at Verona? 6. Who said, “If this be not a lawful case for me to leave his service – look you, sir: he bid me knock him and rap him soundly, sir Well, was it fit for a servant to use his master so?” 7. Who said, “That being a stranger in this city here Do make myself a suitor to your daughter, Unto Bianca, fair and virtuous.” 8. Who said, “Say that she rai: whey then I’ll tell her plain She sings as sweetly as a nightingale. -

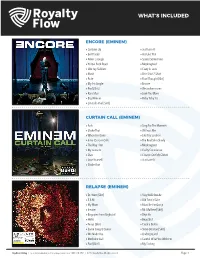

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

Sweet 16 Hot List

Sweet 16 Hot List Song Artist Happy Pharrell Best Day of My Life American Authors Run Run Run Talk Dirty to Me Jason Derulo Timber Pitbull Demons & Radioactive Imagine Dragons Dark Horse Katy Perry Find You Zedd Pumping Blood NoNoNo Animals Martin Garrix Empire State of Mind Jay Z The Monster Eminem Blurred Lines We found Love Rihanna/Calvin Love Me Again John Newman Dare You Hardwell Don't Say Goodnight Hot Chella Rae All Night Icona Pop Wild Heart The Vamps Tennis Court & Royals Lorde Songs by Coldplay Counting Stars One Republic Get Lucky Daft punk Sexy Back Justin Timberland Ain't it Fun Paramore City of Angels 30 Seconds Walking on a Dream Empire of the Sun If I loose Myself One Republic (w/Allesso mix) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall mix Coldplay & Swedish Mafia Hey Ho The Lumineers Turbulence Laidback Luke Steve Aoki Lil Jon Pursuit of Happiness Steve Aoki Heads will roll Yeah yeah yeah's A-trak remix Mercy Kanye West Crazy in love Beyonce and Jay-z Pop that Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Drake Reason Nervo & Hook N Sling All night longer Sammy Adams Timber Ke$ha, Pitbull Alive Krewella Teach me how to dougie Cali Swag District Aye ladies Travis Porter #GETITRIGHT Miley Cyrus We can't stop Miley Cyrus Lip gloss Lil mama Turn down for what Laidback Luke Get low Lil Jon Shots LMFAO We found love Rihanna Hypnotize Biggie Smalls Scream and Shout Cupid Shuffle Wobble Hips Don’t Lie Sexy and I know it International Love Whistle Best Love Song Chris Brown Single Ladies Danza Kuduro Can’t Hold Us Kiss You One direction Don’t You worry Child Don’t -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

Song Ranking Based on Piracy in Peer-To-Peer Networks

10th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2009) SONG RANKING BASED ON PIRACY IN PEER-TO-PEER NETWORKS Noam Koenigstein Yuval Shavitt School of Electrical Engineering Tel Aviv University, Israel {noamk, shavitt}@eng.tau.ac.il ABSTRACT board. We measured music piracy using a data set of geo- graphically identified P2P query string, and compared it to Music sales are loosing their role as a means for music dis- songs ranking on the Billborad Hot 100, which measures semination but are still used by the music industry for rank- sales and air plays. We compiled popularity charts based ing artist success, e.g., in the Billboard Magazine chart. on P2P activity, and show a strong correlation between mu- Thus, it was suggested recently to use social networks as sic piracy and legal sales and air plays. We argue that rank- an alternative ranking system; a suggestion which is prob- ing songs through measurement of P2P queries is a good lematic due to the ease of manipulating the list and the dif- predictor of peoples’ taste, and has many advantages over ficulty of implementation. In this work we suggest to use other means of popularity ranking, which were suggested logs of queries from peer-to-peer file-sharing systems for in the past, most notably using social networks [6]. ranking song success. We show that the trend and fluctua- The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: In tions of the popularity of a song in the Billboard list have Section 2 we introduce the data set used in this study, and strong correlation (0.89) to the ones in a list built from the the methodology used to collect it. -

GYPSY LANE SONG LIST TODAY & 90'S

GYPSY LANE SONG LIST TODAY & 90's Uptown Funk (Mark Ronson/Bruno Mars) All About that Bass (Meghan Trainer) Talk Dirty (Jason Derulo) Thriftshop (Mackelmore) Fancy (IGGY) Timber (Pitbull/Keisha) Happy (Pharell Wiliams) Treasure (Bruno Mars) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke/ Pharell) Don’t you worry child (Swedish House) Get Lucky (Daft Punk) Don’t Stop the party (Pittbull) Feel the moment (Pittbull) Girl on Fire (Alecia Keys) Gangham Style (Psy) Harlem Shake (Baauer) I Wanna Dance with Somebody/Hopeless Love (Whitney Houston/Rhianna) Mr Saxobeat (Alexandra Stan) Raise Your Glass (Pink) Good Feeling (Florider) Move like Jagger/Start me Up (Maroon 5/Mick Jagger) Rolling in the Deep/Come on Baby Light my Fire (Adele/Doors) Party Rock Anthem (LMFAO) Everything Tonight (Pittbull/Neyo) Danza Kuduro (Pittbull/Don Omar) Forget You (Ceelo) Dynamite (Tao Cruz) Billionaire (Travie McCoy) California Girls (Katie Perry) OMG (Usher) Shotz (LMFAO) How low Can You Go (Ludacris and Ciara) I Gotta Feeling (BlackEyed Peas) Boom Boom Pow (BlackEyed Peas) Beggin (Madcon) Just Dance (Lady Gaga) Pokerface (Lady Gaga) Bad Romance (Lady Gaga) Blame it on the Alcohol (Jamie Fox/ TPain) Single Ladies (Beyonce) Green light (John Legend) My Life (TI and Rhianna) Whatever you Want (TI) Dead and Gone (TI/ Justin Timberlake) Magic Girl (Robin Thicke) American Boy (Estelle/ Kanye West) Dangerous (Akon) Just Fine (Mary J Blige) World Hold On (Bob Sinclaire) Please don't stop the music (Rhianna) Only Girl in the World (Rhianna) I Kissed a Girl (Katie Perry) Low (FloRider) -

Part 2: Case Studies in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland

Part 2: Case Studies in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland Order with and without the law Institute for Rural Futures: University of New England 2 Order with and without the law Contents CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................................3 1 STUDY TWO: THE CASE STUDIES ..............................................................................................................7 1.1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.1 Managing the environment within rural communities ..................................................................... 9 1.2.2 Conflict resolution at the local community level ............................................................................... 9 1.2.3 Defining environmental crime ........................................................................................................ 10 1.3 STUDY OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 METHOD ................................................................................................................................................ 12 1.4.1 Interviews ....................................................................................................................................... -

Mgm DJ (Top Wedding Songs)

Page 1 of 10 Marygold Manor (Most Played Songs of 2012) 339 songs, 22.4 hours, 2.02 GB Name Artist Time Genre Ain't Goin Down Till The Sun Goes Up Garth Brooks 4:34 Country (fast) Alcohol Brad Paisley 4:54 Country (slow) All For Love Bryan Adams 4:45 Rock (slow) All My Life KCi & Jojo 3:41 R&B (slow) All Shook Up Elvis Presley 1:58 Rock All Summer Long Kid Rock 3:47 Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 2:48 Rock All You Need Is Love The Beatles 3:53 Pop (slow) Amazed LoneStar 4:00 Country (slow) Amazing Aerosmith 5:56 Rock (slow) American Pie Don McLean 8:32 Rock Another Day In Paradise Phil Collins 5:22 Rock Another One Bites The Dust Queen 3:36 Rock Apache (Jump On it) The Sugarhill Gang 4:16 Hip Hop/Rap Are You Gonna Kiss Me or Not Thompson Square 3:09 Country (fast) At Last Etta James 4:22 Oldies Baby Justin Bieber Feat Ludacris 3:34 Pop (fast) Baby's Got Back (I Like Big Butts) (edit) (Cold Start) Sir Mix-A-Lot 3:51 Hip Hop/Rap Back That Azz Up Juvenile 4:28 Hip Hop/Rap Back That Azz Up Juvenile, Lil Wayne & Manny Fresh 4:26 Hip-Hop/Rap Bad Michael Jackson 4:07 Pop (fast) Bad Romance Lady Gaga 4:29 Dance (fast) Be Our Guest (From Disney's ''Beauty And The Beast'') Angela Lansbury & Jerry Orbach 3:43 Pop Beat It Michael Jackson 4:18 Pop (fast) Beautiful Akon ft. -

(Only Music) Gaston

- Belle from “Beauty & the Beast” - no words (only music) Gaston - no words (only music) Be Our Guest - no words (only music) Days In the Sun - no words (only music) Something There - no words (only music) Beauty and the Beast - no words (only music) Evermore - no words (only music) How Does a Moment Last Forever - no words (only music) 3 Doors Down - Away From the Sun Landing In London 311 - Donʼt Tread On Me 38 Special - Caught Up In You Hold On Loosely Second Chance 4 Non Blondes - Whatʼs Up 5 Seconds Of Summer - Sheʼs Kinda Hot 50 Cent - Best Friend Candy Shop Hustlers Ambition I Get Money Outta Control 98 Degrees - Give Me Just One Night - I Do (Cherish You) The Hardest Thing The Way You Want Me True To Your Heart 3rd Strike - No Light AC DC - High Voltage TNT Adam Brand - Ready For Love Adele - Donʼt You Remember He Wonʼt Go Lovesong Skyfall A Great Big World - Say Something Akon - Berautiful Smack That Alabama - Done It This Way Alan Jackson - I Donʼt Even Know Your Name Alessia Cara - Wild Things Alice In Chains - Man In The Box Your Decision Alicia Keys - Girl On Fire Alison Krauss - When You Say Nothing Amanda Watkins - If I Was Over You Andre Mieux - Bedroom Lovers Got To Get It Andy Grammer - Honey Iʼm Good Aretha Franklin - I Never Loved A Man - Ariana Grande - Problem Ashton Shepherd - Look It Up Ashley Gearing - Five More Minutes Audioslave - I Am the Highway Avicii - Hey Brother Wake Me Up Avril Lavigne - Sk8er Boi Bastille -Pompeii Beauty and the Beast - Beauty and the Beast Beyonce - Best Thing I Never Had Big & Rich - 8th of November Bill Hailey & His Comets - Rock Around the Clock Shake Rattle and Roll Billy Ray Cyrus - Couldvʼe Been Me Blackfoot - Train Train Blake Shelton - Boys Round Here Bloodhound Gang - Another Dick With No Balls The Ballad of Chasey Lain Bob Seger - Rock and Roll Never Forgets Bobby Darin - Youʼre The Reason Iʼm Living Bradley Gaskin - Mr.