The Importance of Quixotism in the Philosophy of Miguel De Unamuno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quixote and Legacy of a Caricaturist/Artistic Discourse

Don Quixote and the Legacy of a Caricaturist I Artistic Discourse Rupendra Guha Majumdar University of Delhi In Miguel de Cervantes' last book, The Tria/s Of Persiles and Sigismunda, a Byzantine romance published posthumously a year after his death in 1616 but declared as being dedicated to the Count of Lemos in the second part of Don Quixote, a basic aesthetie principIe conjoining literature and art was underscored: "Fiction, poetry and painting, in their fundamental conceptions, are in such accord, are so close to each other, that to write a tale is to create pietoríal work, and to paint a pieture is likewise to create poetic work." 1 In focusing on a primal harmony within man's complex potential of literary and artistic expression in tandem, Cervantes was projecting a philosophy that relied less on esoteric, classical ideas of excellence and truth, and more on down-to-earth, unpredictable, starkly naturalistic and incongruous elements of life. "But fiction does not", he said, "maintain an even pace, painting does not confine itself to sublime subjects, nor does poetry devote itself to none but epie themes; for the baseness of lífe has its part in fiction, grass and weeds come into pietures, and poetry sometimes concems itself with humble things.,,2 1 Quoted in Hans Rosenkranz, El Greco and Cervantes (London: Peter Davies, 1932), p.179 2 Ibid.pp.179-180 Run'endra Guha It is, perhaps, not difficult to read in these lines Cervantes' intuitive vindication of the essence of Don Quixote and of it's potential to generate a plural discourse of literature and art in the years to come, at multiple levels of authenticity. -

2022 Spain: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote

Please see the NOTICE ON PROGRAM UPDATES at the bottom of this sample itinerary for details on program changes. Please note that program activities may change in order to adhere to COVID-19 regulations. SPAIN: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote™ For more than a language course, travel to Toledo, Madrid & Salamanca - the perfect setting for a full Spanish experience in Castilla-La Mancha. OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS On this program you will travel to three cities in the heart of Spain, all ★ with rich histories that bring a unique taste of the country with each stop. Improve your Spanish through Start your journey in Madrid, the Spanish capital. Then head to Toledo, language immersion ★ where your Spanish immersion will truly begin and will make up the Walk the historic streets of Toledo, heart of your program experience. Journey west to Salamanca, where known as "the city of three you'll find the third oldest European university and Cervantes' alma cultures" ★ mater. Finally, if you opt to stay for our Homestay Extension, you will live Visit some of Madrid's oldest in Toledo for a week with a local family and explore Almagro, home to restaurants on a tapas tours ★ one of the oldest open air theaters in the world. Go kayaking on the Alto Tajo River ★ Help to run a summer English language camp for Spanish 14-DAY PROGRAM Tuition: $4,399 children Service Hours: 20 ★ Stay an extra week and live with a June 25 – July 8, 2022 Language Hours: 35 Spanish family to perfect your + 7-NIGHT HOMESTAY (OPTIONAL) Max Group Size: 32 Spanish language skills (Homestay July 8 - July 15 Age Range: 14-19 Add 10 service hours add-on only) Add 20 language hours Student-to-Staff Ratio: 8-to-1 Add $1,699 tuition Airport: MAD experienceGLA.com | +1 858-771-0645 | @GLAteens DAILY BREAKDOWN Actual schedule of activities will vary by program session. -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Existentialism

03/05/2017 Existentialism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Existentialism First published Mon Aug 23, 2004; substantive revision Mon Mar 9, 2015 Like “rationalism” and “empiricism,” “existentialism” is a term that belongs to intellectual history. Its definition is thus to some extent one of historical convenience. The term was explicitly adopted as a self description by JeanPaul Sartre, and through the wide dissemination of the postwar literary and philosophical output of Sartre and his associates—notably Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice MerleauPonty, and Albert Camus —existentialism became identified with a cultural movement that flourished in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s. Among the major philosophers identified as existentialists (many of whom—for instance Camus and Heidegger—repudiated the label) were Karl Jaspers, Martin Heidegger, and Martin Buber in Germany, Jean Wahl and Gabriel Marcel in France, the Spaniards José Ortega y Gasset and Miguel de Unamuno, and the Russians Nikolai Berdyaev and Lev Shestov. The nineteenth century philosophers, Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, came to be seen as precursors of the movement. Existentialism was as much a literary phenomenon as a philosophical one. Sartre's own ideas were and are better known through his fictional works (such as Nausea and No Exit) than through his more purely philosophical ones (such as Being and Nothingness and Critique of Dialectical Reason), and the postwar years found a very diverse coterie of writers and artists linked under the term: retrospectively, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, and Kafka were conscripted; in Paris there were Jean Genet, André Gide, André Malraux, and the expatriate Samuel Beckett; the Norwegian Knut Hamsun and the Romanian Eugene Ionesco belong to the club; artists such as Alberto Giacometti and even Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning, and filmmakers such as JeanLuc Godard and Ingmar Bergman were understood in existential terms. -

Iconografía Militar Del Quijote: Emblemas De Aviación1

Revista de la CECEL, 15 2015, pp. 189-206 ISSN: 1578-570-X ICONOGRAFÍA MILITAR DEL QUIJOTE: EMBLEMAS DE AVIACIÓN1 JOSÉ MANUEL PAÑEDA RUIZ UNED RESUMEN ABSTRACT La popular obra de Cervantes ha sido ob- The popular text of Cervantes has received a jeto de una pluralidad de fi guraciones que plurality of confi gurations that have illustrat- han ilustrado la obra; mientras que por otro ed the work; while on the other hand an ex- lado surge en torno a dicho texto una extensa tensive popular iconography arises over the iconografía popular. Sin embargo, las repre- text. However, the representations in the mili- sentaciones en el ámbito militar son escasas, tary fi eld are scarce, being mainly focused in estando centradas principalmente en la esfera the fi eld of aviation. In this study a tour of the de la aviación. En este estudio se realiza un latter has been made, in order to analyze their recorrido por estas últimas, con el fi n de ana- origin, meaning and its relationship with the lizar su procedencia, signifi cado y su relación Quixote. con el Quijote.. PALABRAS CLAVE KEY WORDS Quijote, aviación, iconografía popular, pilo- Quixote, aviation, popular iconography, tos de caza. fi ghter pilots. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN La celebración del III centenario de la publicación de la segunda parte del Quijote2 en 1915 coincidió con otros dos acontecimientos que aunque inicial- mente no guarden relación aparente con la obra cervantina, posteriormente se verá que están intimamente ligados con la línea de trabajo del presente texto. El primero de ellos fue la Guerra Europea o Gran Guerra, o en palabras de Woodrow Wilson, presidente de Estados Unidos: 1 Fecha de recepción: 3 de diciembre de 2015. -

Review of R. M. Flores, Sancho Panza Through Three Hundred Seventy

Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, 61 (1984), 507–08. [email protected] http://bigfoot.com/~daniel.eisenberg R. M. Flores, Sancho Panza through Three Hundred Seventy-five Years of Continuations, Imitations, and Criticism, 1605–1980. Newark, Delaware: Juan de la Cuesta, 1982. x + 233 pp. This is a study of the fortunes of Sancho Panza subsequent to Cervantes, followed by a chapter analyzing ‘Cervantes’ Sancho’. It is a bitter history of what the author views as misinterpretation, a study of ‘disarray, irrelevance, and repetition’, which constitute the overall picture of the topic (149). Included are three bibliogra- phies, one of which is a chronological listing without references, 54 pages of appendices with categorized information about Sancho found in Don Quixote, a tabulation of the length of Sancho’s speeches, and an index of proper names. Flores’ focus in his historical survey is to see if and by whom Sancho has been presented accurately. This is a fair question when dealing with scholarship, but he evaluates creative literature from the same perspective. Thus, a novel of José Larraz López ‘fails to throw any useful light on Sancho’s character’ (105), and we are told that ‘it is impossible to accept [a novel of Jean Camp] as a genuine continuation of Cervantes’ novel’ (105). Flores praises Tolkien because ‘in most…respects the characters of Tolkien and Cervantes are alike’ (108). The question of why a novelist, dramatist, or poet should be expected to be faithful to Cervantes is never addressed, nor is the validity of authorial interpretation and intent explored. Even aside from this, the treatment of creative literature is incomplete, and relies heavily on secondary sources: thus, the discussion of seventeenth-century Spanish images of Sancho is based exclusively on the summary notes in Miguel He- rrero García’s Estimaciones literarias del siglo XVIII. -

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

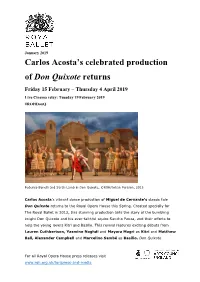

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

From: Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America , 24.1 (2004): 173-88. Copyright © 2004, The Cervantes Society of America. Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote? MICHAEL MCGAHA t will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instrucción written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso origin (Roth 95). The involvement of Miguel’s an- cestors in the cloth business, and his own father Rodrigo’s profes- sion of barber-surgeon—both businesses that in Spain were al- most exclusively in the hand of Jews and conversos—are highly suggestive; his grandfather’s itinerant career as licenciado is so as well (Eisenberg and Sliwa). As Américo Castro often pointed out, if Cervantes were not a cristiano nuevo, it is hard to explain the marginalization he suffered throughout his life (34). He was not rewarded for his courageous service to the Spanish crown as a soldier or for his exemplary behavior during his captivity in Al- giers. Two applications for jobs in the New World—in 1582 and in 1590—were denied. Even his patron the Count of Lemos turn- 173 174 MICHAEL MCGAHA Cervantes ed down his request for a secretarial appointment in the Viceroy- alty of Naples.1 For me, however, the most convincing evidence of Cervantes’ converso background is the attitudes he displays in his work. I find it unbelievable that anyone other than a cristiano nuevo could have written the “Entremés del retablo de las maravi- llas,” for example. -

Nietzsche and Unamuno: Connections and Differences

ISSN: 2347-7474 International Journal Advances in Social Science and Humanities Available online at: www.ijassh.com RESEARCH ARTICLE Nietzsche and Unamuno: Connections and Differences Maria Rodriguez Garcia University Pablo Olavide, Seville, Spain. Abstract This article tries to show the similarities and differences between the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche and Miguel de Unanmuno. For this we refer mainly to the role of Nietzsche's superman and how it is present in the Spanish thinking of the early twentieth century through the work of Miguel de Unamuno. Keywords: Philosophy, Friedrich Nietzsche, Miguel de Unamuno, Metaphysic, Literature. Introduction The last puffs of the 19th century were the negative and the contrast with his writings germ of the approach of the work of situate us in a problematic position, as they Nietzsche to our country, which remained are not few the references found by the sad by the traces of the at present known studious of an influence (more or less like Crisis of the 98 [1] like historical event imperfect) of the thought nietzschean in the that would seat the bases of what would be works of the Spanish thinker. Special the imminent 20th century. According to attention deserves in this point Así hablaba Gonzalo Sobejano in his work Nietzsche in Zaratustra, whose exaltation of the Spain [2], the approach of the authors of the superman and of the eternal return was 98 to the work of Nietzsche was mediated by fundamental in the primes of the Spanish Paul Schmitz, writer and Swiss his pianist 20th century and, specifically, in the that came to Spain in 1899 to remedy an writings unamunianos of these years. -

He Dreams of Giants

From the makers of Lost In La Mancha comes A Tale of Obsession… He Dreams of Giants A film by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe RUNNING TIME: 84 minutes United Kingdom, 2019, DCP, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, Aspect Ratio16:9 PRESS CONTACT: Cinetic Media Ryan Werner and Charlie Olsky 1 SYNOPSIS “Why does anyone create? It’s hard. Life is hard. Art is hard. Doing anything worthwhile is hard.” – Terry Gilliam From the team behind Lost in La Mancha and The Hamster Factor, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is the culmination of a trilogy of documentaries that have followed film director Terry Gilliam over a twenty-five-year period. Charting Gilliam’s final, beleaguered quest to adapt Don Quixote, this documentary is a potent study of creative obsession. For over thirty years, Terry Gilliam has dreamed of creating a screen adaptation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. When he first attempted the production in 2000, Gilliam already had the reputation of being a bit of a Quixote himself: a filmmaker whose stories of visionary dreamers raging against gigantic forces mirrored his own artistic battles with the Hollywood machine. The collapse of that infamous and ill-fated production – as documented in Lost in La Mancha – only further cemented Gilliam’s reputation as an idealist chasing an impossible dream. HE DREAMS OF GIANTS picks up Gilliam’s story seventeen years later as he finally mounts the production once again and struggles to finish it. Facing him are a host of new obstacles: budget constraints, a history of compromise and heightened expectations, all compounded by self-doubt, the toll of aging, and the nagging existential question: What is left for an artist when he completes the quest that has defined a large part of his career? 2 Combining immersive verité footage of Gilliam’s production with intimate interviews and archival footage from the director’s entire career, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is a revealing character study of a late-career artist, and a meditation on the value of creativity in the face of mortality. -

Language and Gender in Don Quixote: Teresa Panza As Subject

Language and Gender in Don Quixote: Teresa Panza as Subject Patricia A. Heid University of California, Berkeley Teresa Panza, the wife of Don Quijote’s famous squire Sancho, is depicted in a drawing in Concha Espina’s book, Mujeres del Quijote, as an older and somewhat heavy woman, dressed in the style of the pueblo, with a sensitive facial expression and an overall domestic air. This is, in fact, the way in which we imagine her through most of Part I, when her identity is limited to that of a main character’s wife, and a somewhat unintelligent one at that. Concha Espina herself says that Cervantes’ book offers her to us as “la digna compaflera del buen Sancho, llena de rustiquez y de ignorancia” (90). Other critics have at least recognized that Teresa, like most of Cervantes ’ female characters, exhibits alertness and resolve (Combet 67). Teresa, however, eludes these simple characterizations. Dressed in all the trappings of an ignorant and obedient wife, she bounds over the linguistic and social borders which her gender imposes. In the open space beyond, Teresa develops discourse as a non-gendered subject. Her voice becomes one which her husband must reckon with in the power struggle which forms the context of their language. By analyzing the strategies for control utilized in this conflict, we see that it is similar to another power struggle with which we are quite familiar: that of Don Quijote and Sancho. The parallels discovered between the two highlight important aspects of the way in which Teresa manages her relationship to power, 1 and reveal that both conflicts are fundamentally the same. -

Exhibition Booklet, Printing Cervantes

This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quijote de la Mancha, and of him who wrote the Viaje del Parnaso, after the one by Cesare Caporali di Perusa, and other stray works that may have wandered off without their owner’s name. This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quijote de la Mancha, and of him who wrote the Viaje del Parnaso, after the one by Cesare Caporali di Perusa, and other stray works that may have wandered off without their owner’s name. This man you see here, with aquiline Printingface, chestnut hair, smooth,A LegacyCervantes: unwrinkled of Words brow, and Imagesjoyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; Acknowledgements & Sponsors: With special thanks to the following contributors: Drs. -

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly.