Bruce Lacey Interviewed by Gillian Whiteley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of the British Isles VIPP July 29

The Best of the British Isles VIPP (England, Scotland, Ireland & Wales! July 29 - Aug. 12, 2022 (14 nights ) on the ISLAND PRINCESS Pauls’ Top Ten List: (Top 10 reasons this vacation is for you! ) 10. You’ll visit 10 ports of call in 4 countries- England, Scotland, Wales & Ireland 9. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day! 8. You’ll have a lot of fun- Tom & Rita Paul are personally escorting this trip! 7. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!! 6. At least 36 meals are included - more, if you work at it! 5. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!!! 4. Texas is too hot in August to stay here! 3. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!!!! 2. You deserve to see the British Isles (maybe for the second time) in sheer luxury! # 1 reason: You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!!!!! So, join us! Just think-no nightly hotels, packing & unpacking, we’re going on a real vacation! New ports too! We sail from London (Southampton) to GUERNSEY (St. Peter Port), England- a lush, green island situated near France. CORK (Ireland) allows a chance to “kiss the Blarney stone” as well as enjoy the scenic countryside and villages! On to HOLYHEAD (Wales) then BELFAST (N. -

Discover London

Discover London Page 1 London Welcome to your free “Discover London” city guide. We have put together a quick and easy guide to some of the best sites in London, a guide to going out and shopping as well as transport information. Don’t miss our local guide to London on page 31. Enjoy your visit to London. Visitor information...........................................................................................................Page 3 Tate Modern....................................................................................................................Page 9 London Eye.....................................................................................................................Page 11 The Houses of Parliament...............................................................................................Page 13 Westminster Abbey........................................................................................................Page 15 The Churchill War Rooms...............................................................................................Page 17 Tower of London............................................................................................................Page 19 Tower Bridge..................................................................................................................Page 21 Trafalgar Square.............................................................................................................Page 23 Buckingham Palace.........................................................................................................Page -

London Sightseer

GREAT RIDES LONDON SIGHTSEER London Sightseer An audax through the streets of London? If you’d dismissed city cycling for pleasure, organiser Bill Carnaby shows you something to make you change your mind (Clockwise from et away from its busy thoroughfares If you arrive at around 11.30 they will be changing the above) Tower Bridge, Hyde Park, The Mall, and cycling in London ceases to be guard as you pass Buckingham Palace. The next part the Gherkin, the about jostling for space with buses and is busiest of the route: you take in Trafalgar Square, the London Eye, and the riverside at Richmond. taxis. It becomes instead an absorbing Strand, Fleet Street and Ludgate Hill with a wonderful view If you want to explore mix of green parks, quiet backstreets, as you ride up to St Paul’s Cathedral. You can use the bus the capital, forget the tube: take your bike Griverside vistas and layer upon layer of history. I’ve lanes here, continuing into the City and across Bank to enjoyed cycling in the capital for years and devised Leadenhall Street. Lord Rogers’ Lloyd’s Building is on the the London Sightseer 100k randonee back in 2002 to right and Lord Foster’s 30 St Mary Axe – known popularly as show it to other cyclists. the Gherkin – on the left. The last several hundred years have left London with a A few twisty and cobbled streets later you are at Tower network of small streets that are ideal for exploring by bike. Bridge. This is the old Pool of London and it was said that Together with the numerous parks and the Thames, they you could once cross the river here by walking from ship form the basis of the route. -

Virginia Horse Shows Association, Inc

2 VIRGINIA HORSE SHOWS ASSOCIATION, INC. OFFICERS Walter J. Lee………………………………President Oliver Brown… …………………….Vice President Wendy Mathews…...…….……………....Treasurer Nancy Peterson……..…………………….Secretary Angela Mauck………...…….....Executive Secretary MAILING ADDRESS 400 Rosedale Court, Suite 100 ~ Warrenton, Virginia 20186 (540) 349-0910 ~ Fax: (540) 349-0094 Website: www.vhsa.com E-mail: [email protected] 3 VHSA Official Sponsors Thank you to our Official Sponsors for their continued support of the Virginia Horse Shows Association www.mjhorsetransportation.com www.antares-sellier.com www.theclotheshorse.com www.platinumjumps.com www.equijet.com www.werideemo.com www.LMBoots.com www.vhib.org 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Officers ..................................................................................3 Official Sponsors ...................................................................4 Dedication Page .....................................................................7 Memorial Pages .............................................................. 8~18 President’s Page ..................................................................19 Board of Directors ...............................................................20 Committees ................................................................... 24~35 2021 Regular Program Horse Show Calendar ............. 40~43 2021 Associate Program Horse Show Calendar .......... 46~60 VHSA Special Awards .................................................. 63-65 VHSA Award Photos .................................................. -

Journal ^ Association of Jewish Refugees

VOLUME 7 NO.S MAY 2007 journal ^ Association of Jewish Refugees How the Jewish refugees thanked Britain One of the most striking initiatives ever Jewish Congregation (Belsize Square mounted by the AJR was the 'Thank-You Synagogue), as well as representatives of the Britain' Fund, which evolved out of a Czech and Hungarian refugees. Among them proposal in 1963 that the Jewish refugees were AJR Chairman Alfred S. Dresel, Amold from Central Europe should make a public Horwell, Egon Larsen, Hans Blumenau, gestiire of thanks to their adopted homeland. Hans Jaeger and the indispensable Wemer The idea was the brainchild of Victor Ross, Rosenstock. Happily, two are still with us: a former refugee who had worked in Victor Ross and Carl Flesch, while Eric publishing and journalism and had written Gould's widow Katia has for years been one a humorous account of the refugee of this joumal's much valued proof-readers. experience, Basic British; as readers know, The Mall Room, British Academy The Fund proved an outstanding he still wields an elegant pen today. The which were to be used for the awarding of success. The organisers' target of £40-60,000 AJR, and in particular its chairman, Hans research fellowships and the holding of was easily exceeded; by the time the Fund Reichmann (who died in 1964), had been annual (later biennial) lectures, both under was handed over to the British Academy at thinking along similar lines. After the AJR the auspices of the British Academy, a a ceremony in the Saddlers' Hall on 8 took on the administration of the fund- highly respected institution that to this day November 1965, it had reached £96,000, raising, Ross became co-chairman of the plays a significant role in supporting and several hundred thousand pounds in today's Fund's organising committee, alongside promoting research and scholarship in the money and an astonishing sum for a Werner M. -

Representations of British Probation

British Journal of Community Justice ©2012 Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield ISSN 1475-0279 Vol. 10(2): 5-23 REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH PROBATION OFFICERS IN FILM, TELEVISION DRAMA AND NOVELS 1948-2012 Mike Nellis, Emeritus Professor of Criminal and Community Justice, School of Law, University of Strathclyde Abstract This paper offers an overview of representations of the British probation service in three fictional media over a sixty year period, up to the present time. While there were never as many, and they were never as renowned as representations of police, lawyers and doctors, there are arguably more than has generally been realised. Broadly speaking - although there have always been individual exceptions to general trends - there has been a shift from supportive and optimistic representations to cynical and disillusioned ones, in which the viability of showing care and compassion to offenders is questioned or mocked. This mirrors wider political attempts to change the traditionally welfare-oriented culture of the service to something more punitive. The somewhat random and intermittent production of probation novels, films and television series over the period in questions has had no discernible cumulative impact on public understanding of probation, and it is suggested that the relative absence of iconic media portrayals of its officers, comparable to those achieved in police, legal and medical fiction, has made it more difficult to sustain credible debates about rehabilitation in popular culture. Introduction One of the problems the Probation Service has is that it is not very photogenic. We live with an image driven media and society and unfortunately probation doesn’t present itself well, certainly on television. -

Modern British & Irish

Modern British & Irish Art Tuesday 4 June 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London Modern British & Irish Art Tuesday 4 June 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge Bonhams Enquiries Please see page 2 for bidder Montpelier Street Emma Corke information including after-sale Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7393 3949 collection and shipment London SW7 1HH [email protected] www.bonhams.com Please see back of catalogue Shayn Speed for important notice to bidders Viewing +44 (0) 20 7393 3909 Sunday 2 June 11am to 3pm [email protected] Illustration Monday 3 June 9am to 4.30pm Front cover: Lot 167 Tuesday 4 June 9am to 11am Customer Services Back cover: Lot 19 Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm Inside front: Lot 76 Bids +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Inside back: Lot 179 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Sale Number: 20777 To bid via the internet please visit www.bonhams.com Catalogue: £12 Please note that bids should be submitted no later than 24 hours before the sale. New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting bids. Failure to do this may result in your bids not being processed. Bidding by telephone will only be accepted on a lot with a lower estimate in excess of £400. Live online bidding is available for this sale Please email [email protected] with “Live bidding” in the subject line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service. Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Chairman, Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Jonathan Baddeley, Antony Bennett, Iain Rushbrook, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Group Managing Director, Matthew Bradbury, Harvey Cammell, Simon Cottle, Veronique Scorer, James Stratton, Roger Tappin, Matthew Girling CEO UK and Europe, Andrew Currie, David Dallas, Paul Davidson, Jean Ghika, Shahin Virani, David Williams, Michael Wynell-Mayow. -

Finding Koko

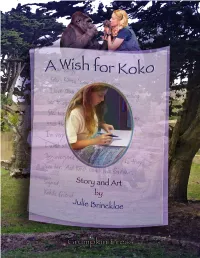

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith's Autumn

Smithers 1 Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith’s Autumn BA Thesis English Language and Culture Annick Smithers 6268218 Supervisor: Simon Cook Second reader: Cathelein Aaftink 26 June 2020 4911 words Smithers 2 Abstract This thesis analyses the way in which intertextuality plays a role in Ali Smith’s Autumn. A discussion of the reception and some readings of the novel show that not much attention has been paid yet to intertextuality in Autumn, or in Smith’s other novels, for that matter. By discussing different theories of the term and highlighting the influence of Bakhtin’s dialogism on intertextuality, this thesis shows that both concepts support an important theme present in Autumn: an awareness and acceptance of different perspectives and voices. Through a close reading, this thesis analyses how this idea is presented in the novel. It argues that Autumn advocates an open-mindedness and shows that, in the novel, this is achieved through a dialogue. This can mainly be seen in scenes where the main characters Elisabeth and Daniel are discussing stories. The novel also shows the reverse of this liberalism: when marginalised voices are silenced. Subsequently, as the story illustrates the state of the UK just before and after the 2016 EU referendum, Autumn demonstrates that the need for a dialogue is more urgent than ever. Smithers 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 “A Brexit Novel” ...................................................................................................................... -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964