Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq Humanitarian Fund (IHF) 1St Standard Allocation 2020 Allocation Strategy (As of 13 May 2020)

Iraq Humanitarian Fund (IHF) 1st Standard Allocation 2020 Allocation Strategy (as of 13 May 2020) Summary Overview o This Allocation Strategy is issued by the Humanitarian Coordinator (HC), in consultation with the Clusters and Advisory Board (AB), to set the IHF funding priorities for the 1st Standard Allocation 2020. o A total amount of up to US$ 12 million is available for this allocation. This allocation strategy paper outlines the allocation priorities and rationale for the prioritization. o This allocation paper also provides strategic direction and a timeline for the allocation process. o The HC in discussion with the AB has set the Allocation criteria as follows; ✓ Only Out-of-camp and other underserved locations ✓ Focus on ICCG priority HRP activities to support COVID-19 Response ✓ Focus on areas of response facing marked resource mobilization challenges Allocation strategy and rationale Situation Overview As of 10 May 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) has confirmed 2,676 cases of COVID-19 in Iraq; 107 fatalities; and 1,702 patients who have recovered from the virus. The Government of Iraq (GOI) and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) have generally relaxed enforcement of the stringent curfews and movement restrictions which have been in place for several weeks, although they are nominally still applicable. Partial lockdowns are currently in force in federal Iraq until 22 May, and in Kurdistan Region of Iraq until 18 May. The WHO and the Ministry of Health recommend maintenance of strict protective measures for all citizens to prevent a resurgence of new cases in the country. The humanitarian community in Iraq is committed to both act now to stem the impact of COVID-19 by protecting those most at risk in already vulnerable humanitarian contexts and continue to support existing humanitarian response plans, in increasingly challenging environments. -

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY on WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT and AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION in the REPUBLIC of IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 the REPUBLIC of IRAQ

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 REPORT IRAQ FINAL THE REPUBLIC OF IN IRRIGATION AGRICULTURE AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT WATER ON COLLECTION SURVEY DATA THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) NTC International Co., Ltd. 7R JR 16-008 英文 118331.402802.28.4.14 作業;藤川 Directorate Map Dohuk N Albil Nineveh Kiekuk As-Sulaymaniyyah Salah ad-Din Tigris river Euphrates river Bagdad Diyala Al-Anbar Babil Wasit Karbala Misan Al-Qadisiyan Al-Najaf Dhi Qar Al-Basrah Al-Muthanna Legend Irrigation Area International boundary Governorate boundary River Location Map of Irrigation Areas ( ii ) Photographs Kick-off meeting with MoWR officials at the conference Explanation to D.G. Directorate of Legal and Contracts of room of MoWR MoWR on the project formulation (Conference room at Both parties exchange observations of Inception report. MoWR) Kick-off meeting with MoA officials at the office of MoA Meeting with MoP at office of D.G. Planning Both parties exchange observations of Inception report. Both parties discussed about project formulation Courtesy call to the Minister of MoA Meeting with representatives of WUA assisted by the JICA JICA side explained the progress of the irrigation sector loan technical cooperation project Phase 1. and further project formulation process. (Conference room of MoWR) ( iii ) Office of AL-Zaidiya WUA AL-Zaidiya WUA office Site field work to investigate WUA activities during the JICA team conducted hearing investigation on water second field survey (Dhi-Qar District) management, farming practice of WUA (Dhi-Qar District) Piet Ghzayel WUA Piet Ghzayel WUA Photo shows the eastern portion of the farmland. -

Poverty Rates

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Mapping Poverty inIraq Mapping Poverty Where are Iraq’s Poor: Poor: Iraq’s are Where Acknowledgements This work was led by Tara Vishwanath (Lead Economist, GPVDR) with a core team comprising Dhiraj Sharma (ETC, GPVDR), Nandini Krishnan (Senior Economist, GPVDR), and Brian Blankespoor (Environment Specialist, DECCT). We are grateful to Dr. Mehdi Al-Alak (Chair of the Poverty Reduction Strategy High Committee and Deputy Minister of Planning), Ms. Najla Ali Murad (Executive General Manager of the Poverty Reduction Strategy), Mr. Serwan Mohamed (Director, KRSO), and Mr. Qusay Raoof Abdulfatah (Liv- ing Conditions Statistics Director, CSO) for their commitment and dedication to the project. We also acknowledge the contribution on the draft report of the members of Poverty Technical High Committee of the Government of Iraq, representatives from academic institutions, the Ministry of Planning, Education and Social Affairs, and colleagues from the Central Statistics Office and the Kurdistan Region Statistics during the Beirut workshop in October 2014. We are thankful to our peer reviewers - Kenneth Simler (Senior Economist, GPVDR) and Nobuo Yoshida (Senior Economist, GPVDR) – for their valuable comments. Finally, we acknowledge the support of TACBF Trust Fund for financing a significant part of the work and the support and encouragement of Ferid Belhaj (Country Director, MNC02), Robert Bou Jaoude (Country Manager, MNCIQ), and Pilar -

Wayfarers in the Libyan Desert

^ « | ^^al^^#w (||^^w<tgKWwl|«^ wft^wl ^ l »Wl l^l^ ^l^l^lll<^«wAwl»^^w^^vliluww)^^^w» ,r,H,«M>f<t«ttaGti«<'^' Wayfarers in the Libyan Desert ) Frances Gordon Alexander With Sixty Illustrations from Photographs and a Map G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Zbc Iknicfterbocfter press 1912 Copyright, 1Q12 BY FRANCES GORDON ALEXANDER Zbc Iftnfcftetbocfecr ptces, "Rcw Korfe CI.A330112 ^ / PREFACE THE following pages are the impressions of two wayfarers who, starting from Cairo, made an expedition into the Libyan Desert, the northeastern corner of the Great Sahara, as far as the oasis of the Fayoum. For two women to start upon a camping trip in the desert, with only an Arab retinue to protect them, seems to some of our friends to show a too high sense of adventure. But it is perfectly safe and feasible. Provided a well recommended 111 Preface dragoman has been selected to take charge of the expediton, one is free from all responsi- bility and care. He provides the camels, donkeys, tents, servants, supplies, and acts as guide, interpreter, and majordomo. The price, part of which is usually paid in advance and the remainder after the journey is finished, is naturally dependent on the size of the caravan. The comfort in which one travels de- pends in part upon the amount of money expended, but in great measure upon the executive ability and honesty of the drago- man. As the licensed dragoman would be answerable if any accident were to befall a party under his charge, every precaution is taken. -

The Role of Tribalism and Sectarianism in Defining the Iraqi National Identity

The Role of Tribalism and Sectarianism in Defining the Iraqi National Identity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Abdallat, Saleh Ayman. 2020. The Role of Tribalism and Sectarianism in Defining the Iraqi National Identity. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365053 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Role of Tribalism and Sectarianism in Defining the Iraqi National Identity Saleh Ayman Abdallat A Thesis in the Field of Middle Eastern Studies for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2020 Copyright 2020 Saleh Ayman Abdallat Abstract In this thesis, I examine the roots that aggravated the Iraqi national identity to devolve into sectarianism. The thesis covers 603 years of historical events that coincided during the time the Ottoman ruled Mesopotamia, until the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003. The thesis is divided into four chapters, in which I address the factors that aggravated to deteriorate the Iraqi national unity. The historical events include the Ottoman-Persian rivalry that lasted for more than three centuries, and the outcomes that precipitated the Iraqi national identity to devolve into sectarianism. Furthermore, the thesis covers the modern history of Iraq during the period that Britain invaded Iraq and appointed the Hashemite to act on their behalf. -

Regime Stability in the Gulf Monarchies

COVER Between Resilience and Revolution: Regime Stability in the Gulf Monarchies Yoel Guzansky with Miriam Goldman and Elise Steinberg Memorandum 193 Between Resilience and Revolution: Regime Stability in the Gulf Monarchies Yoel Guzansky with Miriam Goldman and Elise Steinberg Institute for National Security Studies The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), incorporating the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, was founded in 2006. The purpose of the Institute for National Security Studies is first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel’s national security as well as Middle East regional and international security affairs. Second, the Institute aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are – or should be – at the top of Israel’s national security agenda. INSS seeks to address Israeli decision makers and policymakers, the defense establishment, public opinion makers, the academic community in Israel and abroad, and the general public. INSS publishes research that it deems worthy of public attention, while it maintains a strict policy of non-partisanship. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute, its trustees, boards, research staff, or the organizations and individuals that support its research. Between Resilience and Revolution: Regime Stability in the Gulf Monarchies Yoel Guzansky with Miriam Goldman and Elise Steinberg Memorandum No. 193 July 2019 בין חוסן למהפכה: יציבות המשטרים המלוכניים במפרץ יואל גוז'נסקי, עם מרים גולדמן ואליס שטיינברג Institute for National Security Studies (a public benefit company) 40 Haim Levanon Street POB 39950 Ramat Aviv Tel Aviv 6997556 Israel Tel. -

Iom Emergency Needs Assessments Post February 2006 Displacement in Iraq 1 January 2009 Monthly Report

IOM EMERGENCY NEEDS ASSESSMENTS POST FEBRUARY 2006 DISPLACEMENT IN IRAQ 1 JANUARY 2009 MONTHLY REPORT Following the February 2006 bombing of the Samarra Al-Askari Mosque, escalating sectarian violence in Iraq caused massive displacement, both internal and to locations abroad. In coordination with the Iraqi government’s Ministry of Displacement and Migration (MoDM), IOM continues to assess Iraqi displacement through a network of partners and monitors on the ground. Most displacement over the past five years (since 2003) occurred in 2006 and has since slowed. However, displacement continues to occur in some locations and the humanitarian situation of those already displaced is worsening. Some Iraqis are returning, but their conditions in places of return are extremely difficult. The estimated number of displaced since February 2006 is more than 1.6 million individuals1. SUMMARY OF CURRENT IRAQI DISPLACEMENT AND RETURN: Returns While an estimated 1.6 million individuals are displaced in Iraq, returns continue to grow. This is particularly the case in Baghdad. Many returnees are coming back to find destroyed homes and infrastructure in disrepair. Buildings, pipe and electrical networks, and basic public services such as health care centers are all in need of rehabilitation to meet the needs of returning IDP and refugee families. Transportation for families who wish to return also continues to be an issue. Some families wish to return but do not have the financial resources to travel with their belongings to their places of origin. MoDM has offered 500,000 Iraqi Dinar (IQD), or approximately 432 USD to IDP families returning from another governorate, and they have offered 250,000 IQD for families returning within the same governorate. -

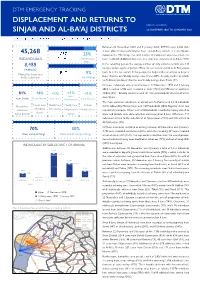

DISPLACEMENT and RETURNS to SINJAR and BAAJ DISTRICTS 03 Jan 2021

DTMDISPLACEMENT EMERGENCY AND RETURNS TO SINJAR TRACKINGAND AL-BA’AJ DISTRICTS DISPLACEMENT AND RETURNS TO PERIOD COVERED: SINJAR AND AL-BA’AJ DISTRICTS 22 NOVEMBER 2020 TO 3 JANUARY 2021 *All charts/graphs in this document show total figures for the period of 8 June 2020 to 3 January 2021 Between 22 November 2020 and 3 January 2021, DTM tracked 4,484 indi- 45,268 viduals (826 families) returning to Sinjar and Al-Ba’aj districts in Iraq’s Ninewa 77% 23% Governorate. This brings the total number of individuals who have taken this INDIVIDUALS Returnees Out-of-camp route to 45,268 (8,488 families) since data collection commenced on 8 June 2020. IDPs 8,488 In this reporting period, the average number of daily individual arrivals was 111 to Sinjar (down significantly from 258 in the last round) and 10 to Al-Ba’aj (down FAMILIES from 16 in the last round). In this period, the daily number of arrivals to Sinjar is Moved to Sinjar and 91% 9% lower than the overall daily average since 8 June (205); the daily number of arrivals Al-Ba’aj districts to Sinjar to Al-Ba’aj to Al-Ba’aj is also lower than the overall daily average since 8 June (19). Of those individuals who arrived between 22 November 2020 and 3 January 2021, a total of 4,106 were recorded in Sinjar (92%) and 378 were recorded in Al-Ba’aj (8%) – broadly consistent with the rates of individuals’ districts of arrival 81% 18% <1% <1% <1% from since 8 June. -

Combat Search and Rescue in Desert Storm / Darrel D. Whitcomb

Combat Search and Rescue in Desert Storm DARREL D. WHITCOMB Colonel, USAFR, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 2006 front.indd 1 11/6/06 3:37:09 PM Air University Library Cataloging Data Whitcomb, Darrel D., 1947- Combat search and rescue in Desert Storm / Darrel D. Whitcomb. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. A rich heritage: the saga of Bengal 505 Alpha—The interim years—Desert Shield— Desert Storm week one—Desert Storm weeks two/three/four—Desert Storm week five—Desert Sabre week six. ISBN 1-58566-153-8 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991—Search and rescue operations. 2. Search and rescue operations—United States—History. 3. United States—Armed Forces—Search and rescue operations. I. Title. 956.704424 –– dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. © Copyright 2006 by Darrel D. Whitcomb ([email protected]). Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii front.indd 2 11/6/06 3:37:10 PM This work is dedicated to the memory of the brave crew of Bengal 15. Without question, without hesitation, eight soldiers went forth to rescue a downed countryman— only three returned. God bless those lost, as they rest in their eternal peace. front.indd 3 11/6/06 3:37:10 PM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . -

Research Memorandum RNA-6, October 12, 1961 the Syrian Army Coup Which Resulted in the Secession of Syria from the United Arab R

1 2 cms PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE ins 1 1 2 ' Ref.: fa -3^-1 / / 57 -g 2> 7 "ff'SOZS Piesise note that this copy is supplied subject to the Public Record Office's terms and conditions and that your use of it may be subject to copyright restrictions. Further information is given in the enclosed Terms and Conditions of supply of Public Records' leaflet CONFIDENTIAi/NOFORN DEPARTMENT OF STATE BUREAU OF INTELLIGENCE AND RESEARCH Research Memorandum RNA-6, October 12, 1961 IMPLICATIONS OF SYRIA'S SECESSION FROM THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC ABSTRACT The Syrian army coup which resulted in the secession of Syria from the United Arab Republic has dealt a serious blow to Nasser's prestige, has opened the way for a renewal of intense partisan strife in Syria, has exacerbated the controversy over Arab unity, and probably will make Syria again a focal point of inter-Arab rivalry. The conservative regime that emerged from the coup faces the difficult task of reorienting Syrian policy away from Nasser's state socialism while convincing the workers and peasants that the essentials of the grains they made since 1958 will be preserved. The regime will also have to contend with mounting communist pressures as the Communist party seeks to regain the position of influence it occupied before the formation of the UAR. Its most serious economic problems will be in the field of finance. Although Syria's defection has not had any immediate serious repercussions in Egypt, the regime may be weakened by disputes as Nasser seeks to put the blame for the Syrian fiasco on some of his lieutenants, notably Marshal 'Amir. -

Iraq- Kerbala Governorate, Kerbala District ( (

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Kerbala Governorate, Kerbala District ( ( ( Jurf as ( Turkey Sakhr Falluja District IQ-P08109 Mosul! ! Erbil اﻟﻔﻠوﺟﺔ IQ-D002 BSyaribaylon GovernoIrrante ( aghdad ﺑBﺎﺑل Ramadi! !\ IQ-G06 Jordan Najaf! Musayab District Basrah! ) ) ) Mulla اﻟﻣﺳﯾب Saudi Arabia KuwaRitajab ( IQ-D037 IQ-P08121 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Kareid (( kwnah ( ( ( IQ-P08112 ( ( ( ( ( Makiheil wa ( ( ( al-haswah IQ-P16306 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Al-qertah ( IQ-P16117 ( Um Rewah Al-thalthany IQ-P15974 IQ-P15816 ( ( Al Shreefat ( ( ( Masleikh ( ( ( - 12 ( ( IQ-P16308 Al-Swadah 1 Hadi Ibrahim ( ( IQ-P16046 ( IQ-P16127 ( IQ-P15844 Karwd ( Um Gharagher al-sharkeiah (( IQ-P16331 ( Al-Amel Haswat Al A'wara IQ-(P15884 Camp Karwd ( ( Mutlak Al Gharbiya ( ( ( IQ-P15572 ( al-hamodeiah ( IQ-P16176 Al-shareifat IQ-P16016 Al-razazah ( ( IQ-P15883 ( IQ-P16125 Um gharagher ( IQ-P16120 Al Anwar Al-sharei'ah ( ( ( Qal`at Sayyid IQ-P15970 ( Al-kamaleiah IQ-P16013 IQ-P16124 ( ( ( ( Muhammad ( IQ-P16105 Al-faidhiyah North Al-Kass ( IQ-P16317 Hay Al Hay ( IQ-P16077 IQ-P15931 ( ( Zira'a(( Al-Share'a Bad'ah aswad ( Razaza Al Wafa'a ( IQ-P(1(6204 Ansar (( IQ-P16264 IQ-P16050 Bad'ah IQ-P16146 ( ( ( IQ-P16321 ( Al-gadhy (( ( ( ( IQ-P15830 Alhaj ( Al-Naqeib shareif ( ( ( ( IQ-P16082 ( ( Imam `Awn ( ( ( Kadhim IQ-P16114 IQ-P16147 IQ-P16287 ( ( ( ( Bas(atein ( ( IQ-P16090 ( ( al-karchi ( Al Husayniyah ( Al Hurr ( ( ( ( IQ-P1(6157 Al-zubaidat (( ( Al-salameiah Hay al-'askary Bad'ah ( ( ( ( IQ-(P16139 al-(sharkeiah al-thanei 'aeishah Mustafah ((( ( ((( IQ-P15797 IQ-P16222 IQ-P16145 khan ( ( Na'amah -

English and French Speaking Individuals and Labeled TV and Living in Um-Qasr Hospital

ISGP-2003-00027262 UNCLASSIFIED//FOUO [Page 3:] In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful Summary report of Department 27 for 2 April 2003 1. a. At 0800 on 2 April, the enemy carried out a military airborne drop near observation post (800), Amiriyah Al-Fallujah. On 1 April about 100 tanks were seen near the same observation post. b. At 1840 on 1 April, an airborne drop took place about 15 Kilometers from east Barwanah, Haditah. c. At 6:50 on April, the enemy conducted an airborne drop of tanks in the city of Al- Nu’maniyah 2. Large reinforcements on a convoy in Al-Hay, Kut supported by around 15 to 20 helicopters. There are also reinforcements on the convoy that passed Al-Nu’maniyah going towards Al-Aziziyah road. Stations of Wasit 3. Information from the air force security based on letter from Al-Qadisiyyah base showed that the enemy is currently in H 1 airport in 10 to 12 tanks supported by 2 helicopters. The enemy attacked the force guarding Al-Qadisiyyah dam and was able to take it over with a small force. A force from the Party and Ghazah Brigade are heading towards it. 4. At 1050 an enemy convoy is moving towards Al-Zubaydiyah from Al- Nu’maniyah. The enemy convoy is currently about 15 Kilometers north of Al- Nu’maniyah across from [illegible] going towards Al-Zubaydiyah and Sawirah to Wasit. At 1100, the enemy has advanced with [illegible] force towards Kut and the fighting is still ongoing. 5. The information indicates that the enemy has crosses the Euphrates from Al-Hay region with a force of [illegible], trucks, and administrative services going towards [illegible].