International Communication” Revised Pages Revised Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

Broadcasting Jul 1

The Fifth Estate Broadcasting Jul 1 You'll find more women watching Good Company than all other programs combined: Company 'Monday - Friday 3 -4 PM 60% Women 18 -49 55% Total Women Nielsen, DMA, May, 1985 Subject to limitations of survey KSTP -TV Minneapoliso St. Paul [u nunc m' h5 TP t 5 c e! (612) 646 -5555, or your nearest Petry office Z119£ 1V ll3MXVW SO4ii 9016 ZZI W00b svs-lnv SS/ADN >IMP 49£71 ZI19£ It's hours past dinner and a young child hasn't been seen since he left the playground around noon. Because this nightmare is a very real problem .. When a child is missing, it is the most emotionally exhausting experience a family may ever face. To help parents take action if this tragedy should ever occur, WKJF -AM and WKJF -FM organized a program to provide the most precise child identification possible. These Fetzer radio stations contacted a local video movie dealer and the Cadillac area Jaycees to create video prints of each participating child as the youngster talked and moved. Afterwards, area law enforce- ment agencies were given the video tape for their permanent files. WKJF -AM/FM organized and publicized the program, the Jaycees donated man- power, and the video movie dealer donated the taping services-all absolutely free to the families. The child video print program enjoyed area -wide participation and is scheduled for an update. Providing records that give parents a fighting chance in the search for missing youngsters is all a part of the Fetzer tradition of total community involvement. -

Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning David Michael Westlake

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2005 Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning David Michael Westlake Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Westlake, David Michael, "Fantasy and Imagination: Discovering the Threshold of Meaning" (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 477. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/477 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. FANTASY AND IMAGINATION: DISCOVERING THE THRESHOLD OF MEANING BY David Michael Westlake B.A. University of Maine, 1997 A MASTER PROJECT Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2005 Advisory Committee: Kristina Passman, Associate Professor of Classical Language and Literature, Advisor Jay Bregrnan, Professor of History Nancy Ogle, Professor of Music FANTASY AND IMAGINATION: DISCOVERING THE THRESHOLD OF MEANING By David Michael Westlake Thesis Advisor: Dr. Kristina Passman An Abstract of the Master Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) May, 2005 This thesis addresses the ultimate question of western humanity; how does one find meaning in the present era? It offers the reader one powerful way for this to happen, and that is through the stories found in the pages of Fantasy literature. It begins with Frederick Nietzsche's declaration that, "God is dead." This describes the situation of men and women in his time and today. -

Terhi Rantanen LSE Media Globalization So Much Has

Terhi Rantanen LSE Media Globalization So much has happened since the word globalization was first introduced in the early 1990s. Originally introduced as a concept of something positive that would transform many worlds into one – something, as Albrow put it, ‘by which the peoples of the world are incorporated into a single world society, global society’ (Albrow, 1990: 45), and even into a ‘global village’ (McLuhan (1964/1994), it is increasingly seen in negative terms. Soon after its introduction the very word it became a target of anti-globalization movements protesting against unforeseen consequences of injustices accompanying globalization around the world. Rarely has an academic concept so quickly reached the streets and so rapidly become a symbol of inequality. What anti-globalization demonstrators, who often identified themselves also as anti-capitalist and anti-neoliberalist, could not foresee was that right-wing populist parties would also start blaming globalization for the erosion of national economies, politics and culture. As the Financial Times wrote, Mr Trump’s sweeping rhetoric and compulsive tweeting resonated among millions of Americans who have felt marginalized by globalization. In the US, as told by Mr Trump, globalization and free trade have rewarded only a privileged few. There is a kernel of truth in Mr Trump’s generalizations, to which more centrist leaders have given too little notice. Inequality has risen and median incomes have stagnated or fallen in recent years, especially among those without a college degree (Donald Trump’s victory challenges the global liberal order, 2016). Today, at least in Europe and the United States, it often looks as if globalization has become Public Enemy Number One for both right- and left-wing movements and parties. -

Global Studies - CPS Specialty (GBST) 1 Global Studies - CPS Specialty (GBST)

Global Studies - CPS Specialty (GBST) 1 Global Studies - CPS Specialty (GBST) Search GBST Courses using FocusSearch (http:// catalog.northeastern.edu/class-search/?subject=GBST) GBST 1011. Globalization and International Affairs. (4 Hours) Offers an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing global/international affairs. Examines the politics, economics, culture, and history of current international issues through lectures, guest lectures, film, case studies, and readings across the disciplines. GBST 1012. The Global Learning Experience. (1 Hour) Examines global citizenship in the 21st century. Introduces the concepts of global citizenship, cosmopolitanism, pluralism, and culture. Connects local issues at host sites with broader dynamics of globalization, migration, positionality, power, and privilege.#Offers opportunities to analyze and apply ideas through personal reflection, application of intercultural theory, and team-based problem solving. GBST 1020. Community Learning 1. (1 Hour) Offers an introduction to community learning, social justice, and cross- cultural collaboration in Boston. The main objective is to help students prepare for, gain from, and reflect upon their semester in Boston as a profound global experience. Uses lectures, course readings, group discussions, collaborative projects, and semester-long service-learning opportunities to challenge students to ask critical questions and become global citizens and ambassadors by actively participating in their own learning community, as well as the greater Northeastern community, and beyond into Boston. Ongoing, online reflection is designed to help students articulate their own experiences, respond to others’ experiences, and ultimately make connections with the global experiences of others. GBST 1030. Community Learning 2. (1 Hour) Continues the introduction of community learning, social justice, and cross-cultural collaboration begun in GBST 1020. -

Media's Influences on Purchasing of Real Estate --- Case of Guangzhou

Media’s Influences on Purchasing of Real Estate - Case of Guangzhou, China Abstract Key Words: Media’s Influences on Purchasing of Real Estate - Case of Guangzhou, China Lai, Ying, School of Translation and Interpretation, Zhongshan University, Guangzhou Ge, Xin Janet, School of the Built Environment, University of Technology Sydney, Australia. Abstract This study endeavors to provide an overall view of the Cantonese’ usage of media and how it affects their expectations in the purchase of real estate, to better understand the real estate market in Guangzhou. Mass media, as a most prominent element in real estate marketing communication, has increasingly significant effects on the decisions of its audiences. However, deeply rooted Chinese traditional notions direct the purchases as well. A survey is conducted to explore the influences on the purchasing activities of people in Guangzhou. The study is conducted in the following manner: Firstly, the current background of the residential real estate market and mediums in real estate advertising and communication are briefly illustrated. Secondly, mass media theory and literature on media’s influence on purchasing are briefly reviewed. Thirdly, the survey design and data collection procedures are described. Finally, the elements of real estate preferences, and how Chinese traditional notions affect property purchasing activities are analyzed. The findings suggest that the media takes an overwhelmingly important role in providing information on property, whereas the opinions of relatives or friends are most influential when making decisions. The characteristics of a property are always emphasized by the agents during promotion; and the Cantonese welcome various types of housing as they are living in a relatively open and prosperous city. -

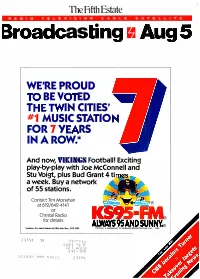

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

The Digital Divide: a Digital Bangladesh by 2021?

International Journal of Education and Human Developments Vol. 1 No. 3; November 2015 The Digital Divide: A digital Bangladesh by 2021? Kristen Waughen, Ph.D. Students In Free Enterprise Sam M Walton Fellow Elizabethtown College Department of Math and Computer Sciences Elizabethtown, PA 17022, USA. Abstract The purpose of this research was to define and identify the digital divide and the various considerations that factor into a country’s technological status. The goal was to investigate the current technological position of Bangladesh, and gaps in their progress because they aim to be a Digital Bangladesh by 2021. The digital divide can be witnessed all over the world between countries and within countries, and there are various aspects that contribute to this situation. Some of the characteristics are access, education, economics, social relationships, income, age, geographical location, government, and the technological skills of teachers, students, and people. One more significant characteristic is the number of children in the household. Also, developed versus developing countries have similar issues on different scales, but together these characteristics affect the success of digital lifestyle of a region or country. Keywords: digital divide, knowledge, poor, barriers, Internet, communication, technology, education, Bangladesh, GDP Elements of the Divide One important element for a country in the 21st century is its technological advancement. Availability, usage, and diffusion of the technology throughout the country are three considerations. One term often used to describe this status is the digital divide (Prensky, 2001). The first computer used in Bangladesh was a mainframe in 1964 (SDNP Bangladesh, 2000). What has happened since then? I will explore the following components of the digital divide in Bangladesh: access to the Internet and computer/mobile devices, amount of education of its citizens, role of the government and the community, the skills of the teachers, and quality and quantity of the information available. -

The Central and Eastern European Online Library

You have downloaded a document from The Central and Eastern European Online Library The joined archive of hundreds of Central-, East- and South-East-European publishers, research institutes, and various content providers Source: CM Komunikacija i mediji CM Communication and Media Location: Serbia Author(s): Hans J. Kleinsteuber, Barbara Thomass Title: Comparing Media Systems: The European Dimension Comparing Media Systems: The European Dimension Issue: 16/2010 Citation Hans J. Kleinsteuber, Barbara Thomass. "Comparing Media Systems: The European style: Dimension". CM Komunikacija i mediji 16:5-20. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=547527 CEEOL copyright 2019 Comparing media systems: The European Dimension Hans J. Kleinsteuber1 Barbara Thomass2 UDC 316.774 : 659.3(4) Summary: Comparative media studies have become a central research area within academic media research. International comparison of media systems has undergone an impressive development in the last five decades. This article is about the classic contri- bution to the study of comparative media systems and what this means for Europe. The authors present short description of the major contributions and after that relate them to the European experience. Starting point of comparative media analysis was the question “Why is the press as it is?” as Siebert, Peterson, and Schramm put it in 1956, when they published their famous comparative study which claimed, not only to explain what the press does and why, but, as the subtitle claimed, What the Press Should Be and Do. Key words: media systems, globalization, internationalization Media systems are embedded in their social environment which is both culturally and nationally shaped environment. -

Mergers & Acquisitions

Mergers & Acquisitions: The Case Grupo Media Capital and PT Portugal Pedro Barreto Goulão Crespo Student Number – 152114216 Advisor: Professor Henrique Bonfim June 2016 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree Master in Management with Major in Corporate Finance, at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa 2016 Abstract Over the last 2 years, Altice Group has been one of the most active telecommunication companies, making acquisitions in different countries, not only in the telecommunication sector but also in the media sector. According to the multinational company, the expansion into the media industry, in the countries where they have already telecommunication operations, brings many and important synergies to their overall operation. After Altice have bought PT Portugal, some rumors came up about the possibility of Altice also entering in the media market in Portugal. Taking up these rumors I decided to study the potential acquisition of Grupo Media Capital by Grupo Altice, through PT Portugal. Along the thesis, I explain relevant M&A literature, make a review on both sectors (media and telecommunication) and companies, and at the end also calculate the standalone valuation of both companies and the synergies that may arise from this deal. After all these procedures, I conclude that this is the perfect moment for PT Portugal to make an offer to Group Prisa (Grupo Media Capital major shareholder). Grupo Prisa should be willing to disinvest in their Portuguese position and taking into account my calculations, Grupo Media Capital share price is undervalued. PT Portugal should make an offer of €4.84 per share, if considering a premium composed by 75% of the cost reduction synergy and 25% of the advertising revenue synergy. -

Article Consumer Databases and The

Consumer Databases and the Commercial Article Mediation of Identity: a medium theory analysis Vincent Manzerolle Sandra Smeltzer University of Western Ontario, Canada. University of Western Ontario, Canada. [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper argues that the systemic nature of contemporary consumer surveillance undermines the most fundamental principle of free market economics: consumer sovereignty. Specifically, this paper argues that the rise of an information society in conjunction with neoliberal capitalism has entrenched routine forms of surveillance within commercial strategies by employing networked databases as a primary medium for the articulation of consumer sovereignty. The communicative relationship between consumers and producers within the market involves effectively ‘listening’ (and then responding) to consumer needs and wants in a timely manner. Surveillance is therefore not only necessary for the operation of globalized consumer capitalism, it is also the primary means by which consumers communicate their sovereignty within the marketplace. By turning to the work of Harold Innis and the intellectual tradition known as medium theory, this paper will theorize how consumer databases are used to circumvent the fundamental neutrality of the market, and thus sovereignty, of individual consumers by exploiting individual vulnerabilities through behaviour and profile modelling. Increasingly, vast amounts of personal information are in the hands of third party entities, creating what Innis calls monopolies of knowledge. Drawing on the example of Acxiom, a US-based data collection and management corporation, we highlight how the commercial mediation of identity has become progressively more hidden from view of the consumer and thus the need for greater regulation of this industry. Introduction Personal information is increasingly the basic fuel on which economic activity runs. -

Mcluhan Lecture

MediaTropes eJournal Vol I (2008): 19–41 ISSN 1913-6005 “AGENTS OF AGGRESSIVE ORDER”: LETTERS, HANDS, AND THE GRASPING POWER OF TEETH IN THE EARLY CANADIAN TORTURE NARRATIVE MONIQUE TSCHOFEN Introduction This paper brings together a most fascinating and under-examined body of early New World writing that belong to a genre of writing I call “the torture narrative” with the insights of Marshall McLuhan in order to offer a way of thinking about body parts, especially hands, teeth, tongues, and eyeballs, and their extensions through technologies such as alphabets, manuscripts, books, and weapons. At its core are questions about the nature and effects of the changes wrought by the early-Gutenberg era—a period characterized by vast scientific and technical discoveries, rising nationalisms, explorations, and conquests—in the New World. Rather than explore the ways an early New World print culture reflects or distorts discrete historical or ethnographic facts about colonial contact, I want to probe the ways the torture narrative speaks to the conditions of speaking and writing, and therefore to the discursive and textual production of the New World subject and New World space. My inquiry seeks to understand both the violence in, and the violence of, representation at founding historical moments, but its relevance far exceeds Renaissance or American studies. At stake in this discussion is an appreciation of a mode of intellectual inquiry that is attentive to the relationship between media technologies and the social worlds they reflect and transform. I. McLuhan’s Theories: Break-Boundaries and the Effects of Alphabetization Fascinated by turbulence, over-heating, explosions, implosions, and reversals, Marshall McLuhan is a thinker of boundaries, limits, and all modalities of transformation.