Rural Restructuring and Rural In-Migration Patterns in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q3central Bank Quarterly Bulletin

JULY 11 JULY Q3 Central Bank Quarterly Bulletin Central Bank of Ireland Quarterly Bulletin 03 / July 11 © Central Bank of Ireland 2011 Contents Section 1 Forecast Summary Table 6 Comment 7 The Domestic Economy 9 Box A: The Impact of the Car Scrappage Scheme on Retail Sales Box B: Relative Trends in Irish Services Producer Prices An Timpeallacht Gheilleagrach 33 Financing Developments in the Irish Economy 35 Box 1: Developments in Retail Interest Rate Margins Developments in the International and Euro Area Economy 53 Box 1: Recent Developments in Euro Area Housing Markets Box 2: A Study of Irish Trade with China Recent Economic Research Publications 68 Section 2 The Rise and Fall of Sectoral Net Wealth in Ireland 70 Mary Cussen and Gillian Phelan Using the Bank Lending Survey to Understand the Recent Disruption to Financial Markets: An Overview 83 Bernard Kennedy Meeting the Statistical Challenges of Financial Innovation: Introducing New Data on Securitisation 109 Brian Godfrey and Clive Jackson Section 3 Statistical Appendix Notes 1. The permission of the Government has been obtained for the use in this Bulletin of certain material compiled by the Central Statistics Office and Government Departments. The Bulletin also contains material which has been made available by the courtesy of licensed banks and other financial institutions. 2. Unless otherwise stated, statistics refer to the State, i.e., Ireland exclusive of Northern Ireland. 3. In some cases, owing to the rounding of figures, components do not add to the totals shown. 4. The method of seasonal adjustment used in the Bank is that of the US Bureau of the Census X-11 variant. -

Health Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan 2019-2024

Health Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan 2019-2024 Prepared under the National Adaptation Framework Prepared by the Department of Health www.gov.ie/health Health Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan 2019-2024 1 Contents Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Development of a Plan for Ireland’s Health Sector, 2019 – 2024 7 Six climate scenarios with profound health implications 8 Predicted climate risks and health impacts for Ireland include: 10 1. Introduction 11 Mandate and vision 12 Health context and the case for adaptation 13 Mainstreaming climate change adaptation 14 Limitations – more research, better data 15 Development of this Plan 16 2. Scene-setting: climate change, health, and Ireland 21 2.1. Health in Ireland, climate in Ireland 22 2.1.1 Health of the population 22 2.1.2 Climate in Ireland 23 2.1.3 Climate change projections for Ireland 23 2.2. Effect of climate change on human health 24 2.3. Health implications of climate change in Ireland 24 2.3.1 Health impacts of temperature changes 24 2.3.2 Health impacts of drought and flooding 29 2.3.3 Health impacts of storms 32 2.3.4 Mental health impacts 32 2.3.5 Risks to health services 32 3. Prioritisation 35 3.1. Climate Impact Screening 36 3.2. Developing Priorities 38 3.3. Climate scenarios – Priority Impacts 41 3.3.1 UV / Sun exposure 41 3.3.2 Air pollution 41 3.3.3 Windstorms 41 3.3.4 Heat / Heatwaves 42 3.3.5 High precipitation / Flooding 43 3.3.6 Extreme cold snaps 43 2 Contents 4. -

Portfolio of Glaslough

An oasis of calm, where the hse is king GLASLOUGH CO MONAGHAN IRELAND INfORMAtION Q pORtfOLIO xxx ENtENtE fLORAL/E EUROpE 2017 CONtENtS foreword ...........................................................1 Beautiful Glaslough .......................................2 planning & Development ...........................3 Natural Environment ...................................5 Built Environment ..........................................7 Landscape ........................................................9 Green Spaces ..............................................10 planting ...........................................................13 Environmental Education ........................15 Effort & Involvement .................................17 tourism & Leisure .....................................18 Community ....................................................21 The Boathouse at Castle Leslie Estate. fOREwORD elcome to beautiful Glaslough, t is a very special privilege to welcome an oasis of calm tucked away the International Jury of Entente Florale Wbetween counties Monaghan, Ito Co. Monaghan to adjudicate Armagh and Tyrone. We were both thrilled Glaslough as one o@f Ireland’s and honoured to be nominated to representatives in this year’s competition. represent Ireland in this year’s Entente Co. Monaghan may not be one of the Florale competition. We hope to do better known tourist destinations of Ireland justice, and that you enjoy the best Ireland, but we are confident that after of scenery and hospitality during your stay spending a day -

Evaluation of the Irish Referendum on Lisbon Treaty, June 2008

Evaluation of the Irish Referendum on Lisbon Treaty, June 2008 Markus Schmidgen democracy international is a network promoting direct democracy. Our basic goal is the establishment of direct democracy (initiative and referendum) as a complement to representative democracy within the European Union and in the nation states. We also work on the general democratisation of the European Union, democratic reform and more direct and participatory democracy worldwide. http://www.democracy-international.org Written by Markus Schmidgen Layout: Ronald Pabst Proof-reading (contents):, Gayle Kinkead, Ronald Pabst, Thomas Rupp Proof-reading (language): Sheena A. Finley, Warren P. Mayr Advice: Dr. Klaus Hofmann, Bruno Kaufmann, Frank Rehmet Please refer all questions to: [email protected] Published by democracy international V 0.9 (4.9.2008) Evaluation of the Irish Referendum on Lisbon Treaty, June 2008 I Introduction This report examines the process of the Irish CONTENT referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon. The referendum was held on June 12, 2008 and was the only referendum on this treaty. The evaluation is I INTRODUCTION .......................................... 3 based on the criteria set by the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe (IRIE). These criteria are internationally recognized as standards to II SETTING...................................................... 4 measure how free and fair a referendum process is conducted. This enables the reader to compare the II.1 Background ................................................... 4 Irish Lisbon referendum to other referendums and to identify the points that could be improved as well II.2 Actors ............................................................. 4 as those that are an example to other nations. II.3 Evaluation...................................................... 7 We at Democracy International and our European partners have already published a series of reports on the EU constitutional referenda of 2005: Juan III CONCLUSION......................................... -

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

目錄 中華民國101年10月05日出版 162

2012 10 季刊 目錄 中華民國101年10月05日出版 162 ■ 會務報導 2 西班牙洛哈230km 5天分站賽陳彥博挑戰成功記者會 5 中華健行102年行事曆 7 本會 101.06.01~101.08.31會務報導 10 懷念林發隊長 / 魏菊江 ■ 專 欄 11 步道的分級(三)愛爾蘭 / 林大裕 15 活躍在當代的古典探險家-日本登山耆宿中村保先生 編譯:林友民、丁雲芝 ■ 山野饗宴 22 歷史颱風 侵台四怪颱 / 陳俊憲 26 登山、健行搭配聰明營養補充,打好你的健康”肌”礎 秘 書 長 : 林文坤 / 副 秘 書 長 : 胡瑞發、曾盛輝 / 江純 執行秘書 : 陳遵憲 行政組長 : 李芳裕 / 行政副組長 : 許如蕙、李素珍 27 人生、友情、機緣 / 張福忠 公關組長 : 張煜鑫 / 公關副組長 : 陳 錦 30 北大武山 / 徐鴻煥 國際組長 : 丁雲芝 / 國際副組長 : 馮一心 活動組長 : 黃俊財 / 活動副組長 : 陳志朋、徐增福、顏德宏 32 精彩的夏天 / 馮一心 嚮導組長 : 劉金龍 / 嚮導副組長 : 劉添盛 39 簡章: 尼泊爾安那普娜基地營 友誼之旅 山安組長 : 鍾德修 / 山安副組長 : 汪 勝 財務組長 : 何玉圓 40 登山教室 會計組長 : 郭淑芬 總務組長 : 鄭匡評 / 總務副組長 : 汪森森 42 玉山盃高地路跑 編輯組長 : 陳秀文 / 編輯副組長 : 顏新輝 43 中華民國山難救助協會「山岳守護基金」 資訊組長 : 莊 福 / 資訊副組長 : 莊文楓 資料組長 : 杜明德 / 資料副組長 : 林月華、呂玉芬 47 中華民國山難救助協會101年10月~102年重點活動計劃 專任幹事 : 邱美麗、黃麗芬 南部辦公室 : 主任 吳一成 / 總幹事 林綉桃 48 本會各縣市分會一覽表 發 行 人 : 陳慶章 主 編 : 林文坤 49 本會101年第四季活動表 發 行 所 : 中華民國健行登山會 地 址 : 台北市朱崙街20號703室 電 話 : (02)2751-0938 傳 真 : (02)2752-4741 網 址 : http://www.alpineclub.org.tw 封面說明: E - mail : [email protected] 郵政劃撥 : 00171103號 聖母峰基地營(EBC)健行 承 製 : 產經網廣告有限公司 攝影:張福忠-中華健行登山會高雄分會 前理事長 地 址 : 台北市中華路二段602號12樓 電 話 : (02)2332-7121 傳 真 : (02)2332-7201 投稿專線 : [email protected] 本會已建立facebook社群網站,歡迎山友加入, 行政院新聞局出版事業登記局版台字第0831 廣結更多的年輕族群參與登山健行的活動。 中華郵政登記為雜誌照碼第3413號 逐夢精神倫奧發揚 國際發光再戰西班牙 西班牙洛哈230km 5天分站賽 『AL ANDALUS ULTIMATE TRAIL 2012』 陳彥博挑戰成功 記者會 在台灣三星電子公司的推薦下,彥博經 過嚴格的審核後於2012年6月24日,有幸成 為台灣有史以來第一位擔任夏季奧運火炬手 的運動員,在英國倫敦讓全世界看見台灣的 驕傲。完成此項任務後,彥博在忙碌的備戰 之下,特地前往溫布敦為好友網球選手謝淑 薇加油。馬不停蹄再直奔578計畫的第六站- 西班牙洛哈230km五天分站賽做實地訓練。 夢想鬥士精神 倫奧點燃 外媒採訪 陳彥博受邀擔任 第 4 2 號 火 炬 手 , 身 穿全套白色火炬手制 服,手舉800克重火 炬,由英國曼徹斯特 南部之斯托克波特自 治區(Stockport)聖火 -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

GEOVIEW Q1 2014 GEOVIEW Quarterly Commercial Vacancy Rates Report

GEOVIEW Q1 2014 GEOVIEW Quarterly CommerCial VaCanCy rates report Analysis of Commercial Buildings in the GeoDirectory Database Q1 2014 This is the first GeoView quarterly analysis for 2014. It provides accurate and up‑to‑date data on the stock of Commercial Properties in Ireland. The information in this report is derived from the GeoDirectory database of commercial address points. This is a comprehensive address database of commercial buildings in the Republic of Ireland. The statistics in this report relate to commercial units as of 31st March 2014. This report includes an once‑off analsyis of commercial vacancy rates in key retail areas in Ireland’s five largest cities. Q1 2014 facts at a glance New in this report Stock of Commercial Properties This issue of GeoView contains an analysis of commercial vacancy rates in selected shopping centres and streets in Cork, Dublin, Galway, Kilkenny and Limerick. 223,336 Total stock of commercial properties These streets and shopping centres contain commercial units involved in different economic sectors but the majority are involved in retail. The comprehensive data includes every 195,545 Total stock of occupied properties business premises on the high streets that were reviewed. Total stock of vacant 27,791 commercial properties Street and Shopping Centre Vacancy Rates Average vacancy rate from selected Vacancy Rates 10.9% shopping centres Average vacancy rate from selected 12.4% Vacancy rate – unchanged from Q4 2013 13. 5% streets Highest vacancy rate recorded for Sligo Find out the streets and shopping centres with the highest and 16.0% – unchanged from Q4 2013 lowest vacancies in each city on pages 5 to 11. -

Cork, Ireland

SHOPPING CENTRE & RETAIL PARK CORK, IRELAND PRIME RETAIL INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY BLACKPOOL SHOPPING CENTRE & RETAIL PARK CORK, IRELAND Introduction JLL and HWBC are delighted to present a unique opportunity to the market to acquire a large-scale retail scheme that is the dominant shopping and office centre in north Cork City. The combined Blackpool Shopping Centre and Retail Park offers an investor a stake in Ireland’s second largest city of Cork. Blackpool is a long established and dominant suburban retail offer effectively fully occupied (98% weighted by value). The package contains two complementary assets providing an investor with the opportunity to purchase 27,846 sq m (299,739 sq ft) of retail space with the benefit of an additional 10,081 sq m (108,513 sq ft) of self-contained offices in a well-designed and integrated mixed use commercial development. Blackpool is the only shopping centre north of the city offering a high concentration of international and nationally recognised retailers including; Dunnes Stores, New Look, Heatons, Next, Aldi, Woodie’s DIY, amongst others. There are also a number of community services provided in the scheme including; council library, post office and state health board. Investment Highlights • Excellent location and dominant retail offer position in its catchment • Destination retail hub with a purpose-built shopping centre and separate open use retail park with overhead modern offices • Long established since year 2000 for the shopping centre and 2004 for the retail park • Occupancy rate of 98% -

Flora & Fauna, Water, Soils, Cultural

ROUTE CONSTRAINTS REPORT SOCIO -ECONOMIC , LANDUSE , LANDSCAPE , FLORA & FAUNA , WATER , SOILS , CULTURAL HERITAGE AND STATION LOCATION REPORT Prepared for Eirgrid to support a Planning Application for the Cavan-Tyrone 400kV Interconnector Project Client: Eirgrid 27 Fitzwilliam Street Lower Dublin 2 By: AOS Planning Limited 4th Floor Red Cow Lane 71 / 72 Brunswick Street North Smithfield Dublin 7 Tel 01 872 1530 Fax 01 872 1519 E-mail: [email protected] www.aosplanning.ie FINAL REPORT - SEPTEMBER 2007 All maps reproduced under licence from Ordnance Survey Ireland Licence No. SU0001105. © Ordnance Survey Ireland Government of Ireland. Cavan-Tyrone 400kV Interconnector Project Table of Contents Section 1 – Executive Summary ......................................................... 5 1.1 The Project .................................................................................. 5 1.2 Route Corridor Alternatives ........................................................... 5 1.3 Key Findings with Regard to Impacts Arising .................................. 5 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................... 6 1.5 Terms of Reference ...................................................................... 6 1.6 Strategic Planning Context ............................................................ 7 1.7 Socio-Economic ............................................................................ 7 1.8 Landuse ...................................................................................... -

Psychiatry in Ireland

36 programmes in Canada. Another is currently doing her intern- virtually non-existent. The services are restricted to the main ship at Harvard Medical School. All of them completed the psychiatric hospital, albeit with some out-patient clinics in 1-year internship at the psychiatric hospital before proceed- general and specialist hospitals. The provision of services at ing abroad for higher psychiatric training. The recruitment primary health and community level is absent. of suitable supervisory senior staff and the documentation of general psychiatry and its sub- specialty training posts should lead to the development of a local postgraduate training Psychiatric research in Kuwait scheme in the country. The Department of Psychiatry, together with the hospital staff at the MOH, has largely been responsible for psychiatric research in the country. It has generated more than 50 Current status of services publications in peer-reviewed international journals during The psychiatric services took a quantum leap with the com- the past 10 years. The research areas have varied with epi- pletion of a new extension to the hospital in 2005. A new demio logical, social and biological psychiatry constituting the block with 262 beds (bringing the hospital’s total to 691) was dominant themes. added and the old drug addiction treatment centre with 100 beds was replaced by a newly built facility with 225 beds. In addition to the existing forensic psychiatry and rehabilitation Outlook units, child and family, and old age psychiatry out-patient services were set up. The hospital staff offers advisory, super- The past decade has witnessed substantial development of visory and consultancy services to the Min istries of Social psychiatric services in Kuwait. -

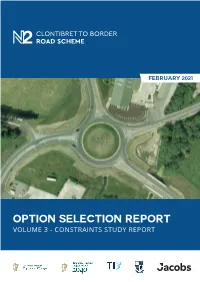

C2B Volume 3

ARDEE – CASTLEBLAYNEY CLONTIBRET – BORDER CLONTIBRET TO BORDER ROAD SCHEME ARDEE – CASTLEBLAYNEY CLONTIBRET – BORDER FEBRUARY 2021 CLONTIBRET ARDEE TO CASTLEBLAYNEY // BORDER ROAD SCHEME CLONTIBRET TO BORDER ROAD SCHEME ARDEE TO CASTLEBLAYNEY ROAD SCHEME CLONTIBRET TO BORDER ROAD SCHEME OPTION SELECTION REPORT rgb rgb // VOLUME22 3 - CONSTRAINTS238 STUDY REPORT 69 60 130 72 #154582 #e83d49 rgb rgb // 44 29 175 29 226 27 #2dafe2 #e8e7e7 [Blank Page] VOLUME 3 - CONSTRAINTS STUDY REPORT N2 Clontibret to Border Road Scheme Project No: 32110000 Document Title: OPTION SELECTION REPORT – VOLUME 3 – CONSTRAINTS STUDY REPORT Document No.: N2-JAC-HWG-C2B-RP-CS-0001 Revision: R0 Document Status: Published Copy Date: February 2021 Client Name: Monaghan County Council Client No: MN/08/3158 & WH0203 Project Manager: Gerry Healy Author: Colm O’Dea File Name: N2-JAC-HWG-C2B-RP-CS-0001.docx Jacobs Engineering Ireland Limited Merrion House Merrion Road Dublin 4, D04 R2C5 Ireland T +353 1 269 5666 F +353 1 269 5497 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2021 Jacobs Engineering Ireland Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party.