Even Unto the Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversion and Revolution in New England Throughout the Fall Of

Introduction: Conversion and Revolution in New England Throughout the Fall of 1765, Stephen Johnson, the pastor of the church in Lyme, Connecticut, excoriated Britain’s Parliament for the Stamp Act and recent trade regulations. Such “evils” imposed on “two millions of free people,” he warned in a series of newspaper editorials, threatened to “destroy the good affections and confidence” between Parliament, King, and America.1 In December, he preached a fast-day sermon (an occasion called by the colony for corporate lamentation) that elucidated the meaning of disrupted “affections.” The “present crisis,” he admitted, was “perplexing and exercising” because it compelled American colonists to make a choice between loyalty to Britain and their “great, provincial, continental, or national purposes.” He put it boldly: “if there be left to the colonies but this single, this dreadful alternative,--slavery or independency,--they will not want time to deliberate which to choose.” Johnson reiterated the need for moral deliberation. As he argued in his newspaper pieces, the “liberty of free inquiry is one of the first and most fundamental [liberties] of a free people.” New Englanders ought to be prepared to determine their political allegiances. Johnson repeated his provocation as a simple question: “what shall we do?”2 This question implied more than the possibility of resistance to parliamentary regulation. It hinted at independence from the British empire. Johnson asked his parishioners, the people of Connecticut, and all Americans to imagine a complete transformation of political loyalties, a renunciation of their status as subjects of the English monarchy. He contended that they had the moral capacity to change their allegiances. -

The Language of the Clergy: Religious and Political Discourse in Revolutionary America, 1754-1783

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 The Language of the Clergy: Religious and Political Discourse in Revolutionary America, 1754-1783 Cristine E. Maglieri College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Maglieri, Cristine E., "The Language of the Clergy: Religious and Political Discourse in Revolutionary America, 1754-1783" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626265. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-vbyq-k788 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LANGUAGE OF THE CLERGY RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL DISCOURSE IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1754-1783 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Cristine E. Maglieri 2000 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts C aju ^ H j YV j6- * 0 . Cristine E. Maglieri Approved, December 2000 Christopher Grasso oL-, A x^ju James Axtell Lu Ann Hom za^ TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Whose Rebellion? Reformed Resistance Theory in America: Part II Sarah Morgan Smith

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of History, Department of History, Politics, and International Politics, and International Studies Studies 4-2018 Whose Rebellion? Reformed Resistance Theory in America: Part II Sarah Morgan Smith Mark David Hall George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/hist_fac Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sarah Morgan and Hall, Mark David, "Whose Rebellion? Reformed Resistance Theory in America: Part II" (2018). Faculty Publications - Department of History, Politics, and International Studies. 84. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/hist_fac/84 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History, Politics, and International Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of History, Politics, and International Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. u SARAH MORGAN SMITH AND MA.RK DAVID HAll Abstract Students of the American Founding routinely assert that America's civic leaders were influenced by secular Lockean political ideas, especially on the question of resistance to tyrannical authority. In the first part of this series, we showed that virtually all Reformed writers, from Calvin to the end of the Glorious Revolution, agreed that tyrants could be actively resisted. The only debated question was who could resist thern. In this essay, we contend that the Reformed approach to active resistance had an important influence on how America's Founders responded to perceived tyrannical actions by Parliament and the Crown. -

A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers: with Some Reflections on the Resistance Made Ot King Charles I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Electronic Texts in American Studies Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1750 A Discourse concerning Unlimited Submission and Non- Resistance to the Higher Powers: With some Reflections on the Resistance made to King Charles I. And on the Anniversary of his Death: In which the Mysterious Doctrine of that Prince's Saintship and Martyrdom is Unriddled (1750). An Online Electronic Text Edition. Jonathan Mayhew A.M., D.D. West (Congregational) Church, Boston Paul Royster , Editor & Depositor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas Part of the American Studies Commons Mayhew, Jonathan A.M., D.D. and Royster, Paul , Editor & Depositor, "A Discourse concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers: With some Reflections on the Resistance made ot King Charles I. And on the Anniversary of his Death: In which the Mysterious Doctrine of that Prince's Saintship and Martyrdom is Unriddled (1750). An Online Electronic Text Edition." (1750). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 44. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Texts in American Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. JONATHAN MAYHEW (1720–1766) -

View of John Winthrop's Career As a Scientist, to Mention the Copy of Euclid, Cambridge, 1655, Which Had Been Used in College Successively by Penn Townsend (A.B

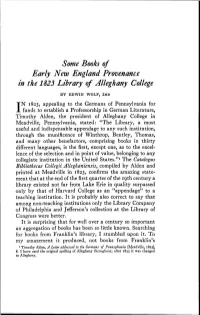

Some Books of Early New England Provenance in the 1823 Library of Alleghany College BY EDWIN WOLF, 2ND N 1823, appealing to the Germans of Pennsylvania for I funds to establish a Professorship in German Literature, Timothy Alden, the president of Alleghany College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, stated: "The Library, a most useful and indispensable appendage to any such institution, through the munificence of Winthrop, Bentley, Thomas, and many other benefactors, comprising books in thirty different languages, is the first, except one, as to the excel- lence of the selection and in point of value, belonging to any collegiate institution in the United States."' The Catalogus Bibliothecae Collegii Alleghaniensis, compiled by Alden and printed at Meadville in 1823, confirms the amazing state- ment that at the end of the first quarter of the 19th century a library existed not far from Lake Erie in quality surpassed only by that of Harvard College as an "appendage" to a teaching institution. It is probably also correct to say that among non-teaching institutions only the Library Company of Philadelphia and Jefferson's collection at the Library of Congress were better. It is surprising that for well over a century so important an aggregation of books has been so little known. Searching for books from Franklin's library, I stumbled upon it. To my amazement it produced, not books from Franklin's ' Timothy Alden, A Letter addressed to the Germans of Pennsylvania [Meadville, 1823], 8. I have used the original spelling of Alleghany throughout; after 1833 it was changed to Allegheny. 14 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, library, but a wealth of New England provenance. -

Samuel Cooper's Old Sermons and New Enemies: Popery And

Note: I provide this essay only as background. My panel talk will summarize Protestant Constitutionalism more generally and also argue for its contemporary relevance. Please contact me with questions: [email protected] Samuel Cooper’s Old Sermons and New Enemies: Popery and Protestant Constitutionalism GLENN A. MOOTS ABSTRACT This article reinterprets the role of Protestantism in the American Revolution by examining the unpublished sermon manuscripts of Boston Congregationalist minister Samuel Cooper. Even as late as 1775, Protestant ministers like Cooper identified Protestantism withlibertyandRomanCatholicismwithtyranny.Butthesesameministerseagerlyallied with Catholic France against Protestant Britain in the Revolution. Cooper even redeployed colonial war sermons against his new British foes in the Revolution. The shifting loyalty of ministers like Cooper cannot be explained by mere expediency or secularization of the political elite. Rather, the explanation lies in the evolving nature of transatlantic Protestant constitutionalism—the ongoing association of Protestantism with liberty and the rule of law—over 2 centuries. On March 15, 1775, off-duty British soldiers and Loyalists held a mock town meeting outside the British Coffee House in Boston. They played their opponents to type and concluded with a costumed mock oration performed by Loyalist surgeon Dr. Thomas Bolton. Publication of Bolton’s oration followed, probably printed by a Loyalist printer outside of Boston. Not coincidentally, March 15 also saw the publication of an oration delivered just 9 days earlier— that year’s official annual oration commemorating the Boston Massacre delivered by Dr. Joseph Warren (Akers 1976, 23–25). The roster of commemorative orators since 1771 was a “who’s who” of Patriot leaders: John Hancock, Glenn A. -

Election Sermon

“&\)C .Sljirlbs of tijr Eartij belong unto ffiob.” AN ELECTION SERMON DELIVERED BEFORE HIS EXCELLENCY JOHN D. LONG, GOVERNOR; HIS HONOR BYRON WESTON, LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR; THE HONORABLE COUNCIL, AND THE LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS, In King's Chapel, Boston, January 4, 1882. BY JOSEPH F. LOVERING, MINISTER OF THE OLD SOUTH CHURCH, WORCESTER, MASS. BOSTON : JSant, gi&erg, Sc Co., Printers to tfje Commontoealtf), 117 Franklin Street. 1882. Commonimaltl] of fllassaclmsctts. House op Representatives, Feb. 1, 1882. Ordered, That a committee of three be appointed to present the thanks of the House to the Rev. Joseph F. Lovering, for the interest- ing and instractive discourse preached before the executive and legislative branches of the State Government on the 4th of January last, and to request a copy of the same for publication. GEO. A. HARDEN, Clerk (Eommontoealtfj of fHassadjusctts. House of Representatives, Boston, Jan. 13, 1882. Reverend and dear Sir, The undersigned have been appointed a committee in behalf of the House of Representatives, to return to you the thanks of the House for the instructive, patriotic, and valuable discourse delivered by you in King’s Chapel, on the 4th inst., before the executive and legislative branches of the State Government, and to ask a copy of the same for publication. Truly “ the shields of the earth belong unto God.” Very respectfully, A. R. MARSHALL. JOHN McFARLEY. O. A. ROBERTS. To the Rev. J. F. Loveking, Worcester, Mass. To A. R. Marshall, John McFarley, O. A. Roberts, Committee of the House of Representatives. Gentlemen, —l am glad to acknowledge the receipt of your letter, informing me of the generous approval of the House of Representatives, expressed by its vote of thanks, of the sermon I had the honor to deliver on the 4th inst. -

"Conservative Revolutionaries" -A Study of the Religious and Political Thought of John Wise, Jonathan Mayhew, Andrew Eliot and Charles Chauncy

"CONSERVATIVE REVOLUTIONARIES" -A STUDY OF THE RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF JOHN WISE, JONATHAN MAYHEW, ANDREW ELIOT AND CHARLES CHAUNCY by John Stephen Oakes M.A., University of Oxford, 1989 M.C.S., Regent College, 1992 M.A., University of British Columbia, 1994 M.DIV., Regent College, 1996 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of History © John Stephen Oakes 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: John Stephen Oakes Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: "Conservative Revolutionaries" -A Study of the Religious and Political Thought of John Wise, Jonathan Mayhew, Andrew Eliot and Charles Chauncy Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Luke Clossey Assistant Professor, Department of History Dr. John Craig Senior Supervisor Professor and Chair, Department of History Dr. Michael Kenny Supervisor Professor, Department of Anthropology Dr. Jack Little Internal Examiner Professor, Department of History Dr. Alan Tully External Examiner Eugene C. Barker Centennial Professor in American History and Chair, Department of History University of Texas, Austin Date Defended!Approved: Janyary 17. 2008 ii SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Decla ration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

The Causes of the American Revolution As Seen by the New England Tories

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 1-1-1970 The causes of the American Revolution as seen by the New England Tories Connie J. McCann University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation McCann, Connie J., "The causes of the American Revolution as seen by the New England Tories" (1970). Student Work. 464. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/464 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CAUSES - OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION AS SEEN BY THE NEW ENGLAND TORIES A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Connie J. McCann January 1970 UMI Number: EP73102 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oissertasion Publishing UMI EP73102 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest’ ProQuest LLC. -

The Craft of Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century America

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 The Craft of Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century America Anne Mary Fuhrman College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Fuhrman, Anne Mary, "The Craft of Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century America" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625718. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-x173-s753 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CRAFT OF PORTRAITURE IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA A Thesis Presented To The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts by Anne M. Fuhrman 1992 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -r'.' --'*'■ ' 2 < r .■/' /•• : ‘ ^ 'S' __ \ Author Approved, April 1992 Graham Hjood i Walter P. Wenska Richard S. Lowry TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS........................................................................................................ -

Of God and Reason in XVIII C. British North America Sobre Dios Y La

ISSN 2007-5308 Of God and Reason in XVIII C. British North America Sobre Dios y la razón en la Norteamérica británica dieciochesca DOI: 10.32870/mycp.v10i28.701 Carlos Acosta Gastélum1 Abstract Resumen The following article intends the description of the El presente artículo tiene por objetivo la des- religious and intellectual environment in prerevo- cripción del contexto religioso e intelectual de la lutionary America. It is divided into two main sec- Norteamérica prerrevolucionaria. Está dividido tions: (1) a religious one where I will cover the most en dos secciones principales: (1) una religiosa en significant elements, and the ideological context donde se abordarán los elementos más signifi- of what was the most decisive cultural force in the cativos y el contexto ideológico de lo que sería la formation of the new country ―Puritanism―; and fuerza cultural más decisiva en la formación del (2) another that succinctly describes the particular futuro país —puritanismo—, y (2) otra que de shape that enlightened thought acquired in that manera sucinta describirá la particular forma que part of the British Empire. el pensamiento ilustrado adquirió en esa región del A description of eighteenth-century Puritan Imperio británico. North America requires a closer look at the ver- Una descripción del puritanismo estadou- sion of Calvinism prevalent in the Northeastern nidense dieciochesco nos obliga a un análisis del seaboard, and therein to the cultural phenomenon calvinismo característico de la costa nororiental, of religious revivalism. Now connected to these así como del fenómeno cultural de los avivamien- variables lie a series of theological conceptions tos religiosos. -

Colonists Respond to the Repeal of the Stamp Act, 1766

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION Library of Congress “Joy to America!” COLONISTS RESPOND TO THE REPEAL OF THE STAMP ACT, 1766 A Selection from News Reports, Broadsides, Sermons, Poetry, An Engraving, A Letter, and A History “So sudden a calm recovered after so violent a storm, is without a parallel in history.” ___David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, 1789 * 1763____ French and Indian War ends with British victory and acquisition of all French territory in North America east of the Mississippi River. 1764____ April: SUGAR ACT & CURRENCY ACT are passed by Parliament. 1765____ March 22: STAMP ACT is passed by Parliament to raise funds for the mainte- nance of British troops in the colonies. The first direct tax imposed on the colonists, it requires the use of tax-stamped paper for all newspapers, magazines, legal documents, etc. Summer/Fall: Public protests, legislative resolutions, and merchant boycotts of British goods occur throughout the colonies. Stamp Act Congress meets in New York with delegates from nine colonies. Nov. 1: Stamp Act takes effect. 1766____ Feb. 13: Benjamin Franklin testifies to the British House of Commons in Paul Revere, A View of the support of repealing the Stamp Act. Obelisk erected under Liberty- March 18: STAMP ACT is repealed. Celebrations occur throughout the colonies. Tree in Boston on the Rejoicings March 18: DECLARATORY Act is passed by Parliament to affirm its authority to for the Repeal of theStamp- “make laws . of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and Act, engraving, 1766, detail people of America .