Transcript by Will Robinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Program Guide

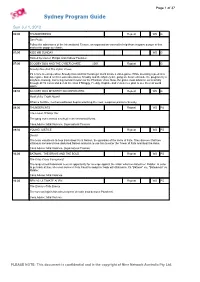

Page 1 of 37 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jul 1, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Sun Probe Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 SCOOBY DOO AND THE CYBER CHASE 2001 Repeat G Scooby Doo And The Cyber Chase It's a race to escape when Scooby-Doo and his friends get stuck inside a video game. While sneaking a peek at a laser game based on their own adventures, Scooby and the Mystery Inc. gang are beamed inside the program by a mayhem-causing, menacing monster known as the Phantom Virus. Now, the game must advance successfully through all 10 levels and defeat the virus if Shaggy, Freddy, Daphne and Velma ever plan to see the real world again. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Howl of the Fright Hound When a horrible, mechanized beast begins attacking the town, suspicion points to Scooby. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG The Forest Of Magi Oar The gang come across a school in an enchanted forest. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Denial The team volunteers to help track down Kent Nelson, the guardian of the Helm of Fate. They discover that two villainous sorcerers have abducted Nelson and plan to use him to enter the Tower of Fate and steal the Helm. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG The Criss Cross Conspiracy! The long-retired Batwoman sees an opportunity for revenge against the villain who humiliated her: Riddler. -

20Th Century Women by Mike Mills EXT

20th Century Women by Mike Mills EXT. OCEAN - DAY High overhead shot looking down on the Pacific Ocean. TITLE: SANTA BARBARA, 1979. EXT. SANTA BARBARA - VONS PARKING LOT - DAY WIDE ON a plume of black smoke rising high into the air. CLOSER ON a 1965 Ford Galaxy engulfed in flames. DOROTHEA (55, short grey hair, Amelia Earhart androgyny) and JAMIE (15, New-Wave/Punk) jog their shopping cart toward the commotion, stunned to find their car in flames. Dorothea looks at the car and then at her son Jamie, concerned. People run for help. Sirens in the background. DOROTHEA (V.O.) That was my husband’s Ford Galaxy. We drove Jamie home from the hospital in that car. JAMIE (V.O.) VISUALS My mom was 40 when she had 1. BABY IN ISOLETTE me. Everyone told her she was too old to be a mother. DOROTHEA (V.O.) VISUALS I put my hand through the 2. DOROTHEA’S HAND OPENING little window, and he’d ISOLETTE WINDOW AND PUTTING squeeze my finger, and I’d HAND THROUGH 3. BABY’S tell him life was very big, FINGERS HOLDING HAND 4. STARS and unknown; IN SPACE JAMIE (V.O.) VISUALS And she told me that there 5. MUYBRIDGE FOOTAGE OF were animals and sky and ANIMALS 6. STILL OF THE SKY cities, 7. CITY FROM DOROTHEA’S ERA DOROTHEA (V.O.) VISUALS Music, movies. He’d fall in 8. BACK TO DOROTHEA’S HAND love, have his own children, OPENING ISOLETTE WINDOW AND have passions, have meaning, PUTTING HAND THROUGH 9. -

Et Tu, Dude? Humor and Philosophy in the Movies of Joel And

ET TU, DUDE? HUMOR AND PHILOSOPHY IN THE MOVIES OF JOEL AND ETHAN COEN A Report of a Senior Study by Geoffrey Bokuniewicz Major: Writing/Communication Maryville College Spring, 2014 Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Faculty Supervisor Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Division Chair Abstract This is a two-part senior thesis revolving around the works of the film writer/directors Joel and Ethan Coen. The first seven chapters deal with the humor and philosophy of the Coens according to formal theories of humor and deep explication of their cross-film themes. Though references are made to most of their films in the study, the five films studied most in-depth are Fargo, The Big Lebowski, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, and A Serious Man. The study looks at common structures across both the Coens’ comedies and dramas and also how certain techniques make people laugh. Above all, this is a study on the production of humor through the lens of two very funny writers. This is also a launching pad for a prospective creative screenplay, and that is the focus of Chapter 8. In that chapter, there is a full treatment of a planned script as well as a significant portion of written script up until the first major plot point. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter - Introduction VII I The Pattern Recognition Theory of Humor in Burn After Reading 1 Explanation and Examples 1 Efficacy and How It Could Help Me 12 II Benign Violation Theory in The Big Lebowski and 16 No Country for Old Men Explanation and Examples -

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

William Urkj O

New Potentials for "Independent" Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. ARCHIVES Signature of Author: Program in Comparative Media Studies , Mo 9, 2008 Certified By: v - William Urkjo Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies / Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: {/- (y Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies New Potentials for "Independent" Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

'Just Like Hitler': Comparisons to Nazism in American Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 5-2010 'Just Like Hitler': Comparisons To Nazism in American Culture Brian Scott Johnson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Brian Scott, "'Just Like Hitler': Comparisons To Nazism in American Culture" (2010). Open Access Dissertations. 233. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/233 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘JUST LIKE HITLER’ COMPARISONS TO NAZISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by BRIAN JOHNSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 English Copyright by Brian Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ‘JUST LIKE HITLER’ COMPARISONS TO NAZISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by BRIAN JOHNSON Approved as to style and content by: ______________________________ Joseph T. Skerrett, Chair ______________________________ James Young, Member ______________________________ Barton Byg, Member ______________________________ Joseph F. Bartolomeo, Department Head -

Poets on Punk Libertines in Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk ©2019 Jet-Tone Press the Ante-Room All Rights Reserved

Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk Libertines in Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love: Poets on Punk ©2019 Jet-Tone Press the Ante-Room All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, of Love: mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Poets on Punk Published by Jet-Tone Press 3839 Piedmont Ave, Oakland, CA 94611 www.Jet-Tone.press Cover design by Joel Gregory Design by Grant Kerber Edited by ISBN: 978-1-7330542-0-1 Jamie Townsend and Grant Kerber Special thanks to Sara Larsen for the title Libertines in the Ante-Room of Love (taken from Sara’s book The Riot Grrrl Thing, Roof Books, 2019), Joel Gregory for the cover, Michael Cross for the extra set of eyes, and Wolfman Books for the love and support. Jet - Tone ©2019 Jet-Tone Press, all rights reserved. Bruce Conner at Mabuhay Gardens 63 Table of Contents: Jim Fisher The Dollar Stop Making Sense: After David Byrne 68 Curtis Emery Introduction 4 Jamie Townsend & Grant Kerber Iggy 70 Grant Kerber Punk Map Scream 6 Sara Larsen Landscape: Los Plugz and Life in the Park with Debris 79 Roberto Tejada Part Time Punks: The Television Personalities 8 Rodney Koeneke On The Tendency of Humans to Form Groups 88 Kate Robinson For Kathleen Hanna 21 Hannah Kezema Oh Bondage Up Yours! 92 Jamie Townsend Hues and Flares 24 Joel Gregory If Punk is a Verb: A Conversation 99 Ariel Resnikoff & Danny Shimoda The End of the Avenida 28 Shane Anderson Just Drifting -

We Can't Help It If We're from Florida’: a Discursive Analysis of the 1980S Gainesville Punk Subculture

‘WE CAN'T HELP IT IF WE'RE FROM FLORIDA’: A DISCURSIVE ANALYSIS OF THE 1980S GAINESVILLE PUNK SUBCULTURE Christos Tzoustas Student No: 5950559 Master of Arts ‘Cultural History of Modern Europe’ Utrecht University Supervisor: dr. Rachel Gillett 2018 ABSTRACT This thesis undertakes a discursive analysis of the 1980s Gainesville punk subculture. As such, it performs a semiotic analysis and close reading to both the textual and visual discursive production of the scene, in the form of flyers, fanzines and liner notes, in order to, on the one hand, examine the ways in which such production was made to signify disorder, and, on the second hand, to illuminate the identity representations that ultimately constructed the Gainesville punk identity. For this reason, it employs the concept of intersectionality in an effort to consider identity representations of gender, race and class as interconnected and overlapping rather than isolated. Finally, it investigates the links between Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection and Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque, on the one hand, and the bodily performativity and corporeal manifestations of the Gainesville punk identity, on the other. Can the punk identity, within its capacity to disturb order, rid the ‘subject’ of its discursive constraints? 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... -

Teaching of Psychology: Ideas and Innovations. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Undergraduate Teaching of Psychology (21St, Kerhonkson, New York, March 28-30, 2007)

Teaching of Psychology: Ideas and Innovations Sponsored by: Psychology Department of Farmingdale State College Proceedings of the 21th Annual Conference on Undergraduate Teaching of Psychology March 28–30, 2007 Editors: Katherine Zaromatidis, Ph.D. Patricia A. Oswald, Ph.D. Judith R. Levine, Ph.D. Gene Indenbaum, Ph.D. 1 Table of Contents Introduction…..Page 3 Conference Program…..Page 4 Counselors as Teachers, Teachers as Counselors: The Process of Parallels John A. Malacos, Ph. D. ….. Page 20 Course Management Systems, Past, Present and Future James Regan, Ph.D., Hugh Knickerbocker & Jodi Allen ….. Page 28 The Hybrid Course: Comparison to Traditional and Distance Learning Courses Katherine Zaromatidis, Ph.D. & Patricia Oswald, Ph.D…… Page 30 The Specifics of Group Discussions within On-line Psychology Classes Anna Toom, Ph.D…… Page 34 The Integration of A Tangential Reading Into Psychology Courses Edward J. Murray, Ph.D. & Carol A. Puthoff Murray, M.A…… Page 36 Do Revisions Help Student Learning? Brandi Scruggs & Emily Soltano ….. Page 42 SITCOMS: TRASH OR TREASURE? Using Situation Comedies to Enhance Learning Dean M. Amadio, Ph.D. & Supriya Poonati ….. Page 46 Student Excuses & Motivation Grant Leitma, Ph.D…… Page 52 Horney Goes Hollywood: Using Films to Teach Personality Theory Dante Mancini, Ph.D. and Herman Huber, Ph.D…… Page 60 Testing Elaboration Learning in Varied Contexts Robert A. Dushay, Ph.D…… Page 61 2 Introduction The 21st Annual Conference on Undergraduate Teaching of Psychology was held on March 28— 30, 2007 at Hudson Valley Resort and Day Spa in Kerhonkson, NY. The conference was sponsored by the Psychology Department of Farmingdale State College. -

Recordings by Women Table of Contents

'• ••':.•.• %*__*& -• '*r-f ":# fc** Si* o. •_ V -;r>"".y:'>^. f/i Anniversary Editi Recordings By Women table of contents Ordering Information 2 Reggae * Calypso 44 Order Blank 3 Rock 45 About Ladyslipper 4 Punk * NewWave 47 Musical Month Club 5 Soul * R&B * Rap * Dance 49 Donor Discount Club 5 Gospel 50 Gift Order Blank 6 Country 50 Gift Certificates 6 Folk * Traditional 52 Free Gifts 7 Blues 58 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Jazz ; 60 Ladyslipper Especially Recommends 8 Classical 62 Women's Spirituality * New Age 9 Spoken 64 Recovery 22 Children's 65 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 "Mehn's Music". 70 Comedy 35 Videos 71 Holiday 35 Kids'Videos 75 International: African 37 Songbooks, Books, Posters 76 Arabic * Middle Eastern 38 Calendars, Cards, T-shirts, Grab-bag 77 Asian 39 Jewelry 78 European 40 Ladyslipper Mailing List 79 Latin American 40 Ladyslipper's Top 40 79 Native American 42 Resources 80 Jewish 43 Readers' Comments 86 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 INQUIRIES: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 ordering information FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are tem CATALOG EXPIRATION AND PRICES: We will honor don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and porarily out of stock on a title, we will automatically prices in this catalog (except in cases of dramatic schools). Make check or money order payable to back-order it unless you include alternatives (should increase) until September. -

The Time Traveler's Wife

When Henry meets Clare, he is twenty-eight and she is twenty. He is a hip librarian; she is a beautiful art student. Henry has never met Clare before; Clare has known Henry since she was six... “A powerfully original love story. BOTTOM LINE: Amazing trip.” —PEOPLE “To those who say there are no new love stories, I heartily recommend The Time Traveler’s Wife, an enchanting novel, which is beautifully crafted and as dazzlingly imaginative as it is dizzyingly romantic.” —SCOTT TUROW AUDREY NIFFENEGGER’S innovative debut, The Time Traveler’s Wife, is the story, of Clare, a beautiful art student, and Henry, an adventuresome librarian, who have known each other since Clare was six and Henry was thirty-six, and were married when Clare was twenty-three and Henry thirty-one. Impossible but true, because Henry is one of the first people diagnosed with Chrono-Displacement Disorder: periodically his genetic clock resets and he finds himself misplaced in time, pulled to moments of emotional gravity from his life, past and future. His disappearances are spontaneous, his experiences unpredictable, alternately harrowing and amusing. The Time Traveler’s Wife depicts the effects of time travel on Henry and Clare’s marriage and their passionate love for each other, as the story unfolds from both points of view. Clare and Henry attempt to live normal lives, pursuing familiar goals— steady jobs, good friends, children of their own. All of this is threatened by something they can neither prevent nor control, making their story intensely moving and entirely unforgettable. THE TIME TRAVELER’S WIFE a novel by Audrey Niffenegger Clock time is our bank manager, tax collector, police inspector; this inner time is our wife. -

The Barber (^Seinfeld) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

:rhe Barber (Seinfeld) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of2 The Barber (^Seinfeld) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "The Barber" is theT2nd episode of the NBC sitcom Seinfeld.It is the eighth episode of the fifth "The Barber" season, and first aired on November ll,1993. Seínfeld episode Plot Episode no. Season 5 Episode 8 The episode begins with George at ajob Directed by Tom Cherones interview. His future employer, Mr. Tuttle, is cut Written by Andy Robin off mid-sentence by an important telephone call, and sends George away without knowing whether Production code 508 he has been hired or not. Mr. Tuttle told George Original air date November ll,1993 that one of the things that make George such an Guest actors attractive hire is that he can "understand everything immediately", so this leaves apuzzling situation. In Jerry's words: "If you call and ask if Wayne Knight as Newman Antony Ponzini as Enzo you have the job, you might lose the job." But if David Ciminello as Gino George doesn't call, he might have been hired and Michael Fairman as Mr. Penske he never know. George will decides that the best Jack Shearer as Mr. Tuttle course of action is to not call at all and to just "show up", pretending that he has been hired and Season 5 episodes start "work", all while Mr. Tuttle is out of town. The thought behind this was that if George has the September 1993 -May 1994 job, then everything will be fine; and if George uThe was not hired, then by the time Tuttle returns, he 1.