'Fighting for the Unity of the Empire'1 Australian Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of Henry Reynolds

Descendants of Henry Reynolds Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of Henry Reynolds 1-Henry Reynolds1 was born on 2 Jun 1639 in Chippenham, Wiltshire and died in 1723 at age 84. Henry married Jane1 about 1671. Jane was born about 1645 and died in 1712 about age 67. They had four children: Henry, Richard, Thomas, and George. 2-Henry Reynolds1 was born in 1673 and died in 1712 at age 39. 2-Richard Reynolds1 was born in 1675 and died in 1745 at age 70. Richard married Anne Adams. They had one daughter: Mariah. 3-Mariah Reynolds1 was born on 29 Mar 1715 and died in 1715. 2-Thomas Reynolds1 was born about 1677 in Southwark, London and died about 1755 in Southwark, London about age 78. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a Colour maker. Thomas married Susannah Cowley1 on 22 Apr 1710 in FMH Southwark. Susannah was born in 1683 and died in 1743 at age 60. They had three children: Thomas, Thomas, and Rachel. 3-Thomas Reynolds1 was born in 1712 and died in 1713 at age 1. 3-Thomas Reynolds1,2,3 was born on 22 May 1714 in Southwark, London and died on 22 Mar 1771 in Westminster, London at age 56. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a Linen Draper. • He worked as a Clothworker in London. Thomas married Mary Foster,1,2 daughter of William Foster and Sarah, on 16 Oct 1733 in Southwark, London. Mary was born on 20 Oct 1712 in Southwark, London and died on 23 Jul 1741 in London at age 28. -

The Report of the Inquiry Into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour

Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR This publication has been published by the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Copies of this publication are available on the Tribunal’s website: www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Editing and design by Biotext, Canberra. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR Senator The Hon. David Feeney Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Parliamentary Secretary, I am pleased to present the report of the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal’s Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour. The Inquiry was conducted in accordance with the Terms of Reference. The Tribunal that conducted the Inquiry arrived unanimously at the findings and recommendations set out in this report. In accordance with the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal Procedural Rules 2011, this report will be published on the Tribunal’s website — www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au — 20 working days after -

U3A Newsletter No. 65

Inc AA0053344W Issue 65 NEWSLETTER 3 May 2021 • Am I eligible? You can apply for the $250 From the Committee payment if you have one of the following: On Anzac Day President Doug McCallum laid a • A Pension Concession Card wreath on behalf of Creswick U3A to honour those • JobSeeker, Youth Allowance, Abstudy or who sacrified more than we could ever have asked Austudy of them in order to enjoy the life we now lead. Not • Veterans Affairs Pensioner Concession Card only did they give their future hopes and dreams, but many suffered the effects for their entire lifetime. It Venue is the Ballarat North Neighbourhood House, behoves us all to never forget these brave men and 6 Crompton Street, Soldiers Hill on Friday 4 June women and the debt we owe them and their families from 11.00am to 3.00pm. Phone 0491 753 307 for for the selfless acts of courage they performed in our further information. defence. A day at the movies Tutors’ Meeting What a day we had at the Regent Multiplex seeing A Tutors’ Meeting will be held in the Scout Hall on 42nd Street, where we had the entire Showcase to Thursday 27 May at 2.30pm please come along and ourselves with super comfortable seats. The movie help us plan the remainder of the year. Some light is a delightful trip down memory lane with familiar refreshments will be provided. RSVP by 20 May. songs, superb costumes and vibrant dance scenes. We were each given a boxed lunch on arrival and New Residents’ Meeting all who went thoroughly enjoyed the afternoon’s The New Residents Meetings will be held on entertainment. -

Muster Rolls, Etc., 1743-1787

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Pennsylvaniaarchives SamuelHazard,JohnBlairLinn,WilliamHenryEgle,GeorgeEdwardReed,ThomasLynchMontgomery,GertrudeMacKinney,CharlesFrancisHoban,Pennsylvania.SecretaryoftheCommonwealth,Dept.PublicInstruction,PennsylvaniaStateLibrary PENNSYLVANIA ARCHIVES jfiftb Seríes VOLUME VII. EDITED BY THOMAS LYNCH MONTGOMERY UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE Hon. FRANK M. FULLER, SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH. HARRISBURG, PA.: HARRISBURG PUBLISHING COMPANT, STATE PRINTER, 1906. Si- 290328 Muster Rolls RELATING TO THE ASSOCIATORS AND MILITIA OF THE COUNTY OF LANCASTER, (a) (1) 1-Vol. VII-5th Ser. (2) COUNTY OF LANCASTER. LANCASTER COUNTY LIEU TENANTS. Bartram Galbraith, June 3, 1777. Samuel John Atlee, Men. 31, 1780. Adam Hubley, Feb. 14, 1781. James Ross, Nov. 17, 1783. LANCASTER COUNTY SUB-LIEUTENANTS. James Crawford, March 12, 1777. Adam Orth, March 12, 1777. Robert Thompson, March 12, 1777. Joshua Elder, March 12, 1777. Christopher Crawford, March 12, 1777. Curtis Grubb, Oct. 23, 1777. William Ross, Oct. 25, 1777. Simon Snyder, Oct. 25, 1777. Christian Wirtz, Oct. 31, 1777. James Cunningham, Apr. 1, 1780. Christopher Kucher, Apr. 1, 1780. Abraham Dehuff, Apr. 1, 1780. John Hopkins, Apr. 1, 1780. John Huber, Apr. 1, 1780. Wm. Steel, Apr. 1, 1780. Maxwell Chambers, Apr. 1, 1780. Jacob Carpenter, Apr. 1, 1780. James Barber, Apr. 1, 1780. Robert Clark, Apr. 1, 1780. Robert Good, June 21, 1780. William Kelley, Feb. 14, 1781. Wiliam Smith, June 29, 1781. Philip Gloninger, May 2, 1781. Adam Orth, Nov. 13, 1782. 4 ASSOCfAfEORS AND MILITIA. 'LANCASTER COUNTY COMMISSIONERS. -

Final Thesis File

The Children’s Court: Implications of a New Jurisdiction Jennifer Marie Anderson https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5562-6383 Williamstown Police Court c. 1890s with children in foreground Andrew Rider (1821 – 1903), State Library Victoria, H86.98/640. Doctor of Philosophy March 2021 Melbourne Law School and School of Social and Political Studies University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ABSTRACT This thesis examines the establishment of Children’s Courts in the state of Victoria through the Children’s Court Act 1906 (Vic) and the campaign for legislative change in the city of Melbourne. It asks as its central question why the foundation of a separate Court was, and continues to be, understood as a primary response to children’s social and economic disadvantage. The thesis employs social history methodologies to show, through close jurisprudential examination of archives, how the Children’s Court was theorised by middle class reformers as a solution to their anxieties about the public behaviour of poor urban children in early twentieth-century Melbourne. It reveals how those anxieties were projected on to concerns over Court environment and procedures, as well as how key decisions about which children should be included within (and excluded from) the new jurisdiction reflected reformers’ social and moral understandings about criminal responsibility, poverty and welfare, race and gender. The thesis also documents the experiences of children who were the subject of historical Court intervention. Their life stories demonstrate the close interrelationship between structural disadvantage and a Court appearance. This research project has both historical and contemporary significance. -

December 1924

GIiH&K OK THE PAPERS LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 4 Notices of Motion and Orders of the Day No. 1. TUESDAY, 15th JULY, 1924. Questions. 1. Mb. Clough : To ask the Honorable the Minister of Railways what decision has been arrived at in connexion with the proposal to remove the moulding shop from the Bendigo Railway Workshops. 2. Mr. Cain : To ask the Honorable the Chief Secretary when the Government intends to give effect to the eight-hour day for employees of mental hospitals, as promised recently in the Premier’s policy speech at Creswick. Order of the Day (to take precedence):— 1. Address in Reply to the Governor’s Speech—Motion for—Resumption of debate. Notices of Motion :— 1. Sir Alexander Peacock : To move, That the Member for Ovens, the Honorable Alfred Arthur Billson, be appointed Chairman of Committees of this House. 2. Mr. Bailey : To move, That he have leave to bring in a Bill intituled “ A BUI to amend, the ‘ Administration and Probate Act 1915 ’ and for other purposes 3. Mr. Farthing : To move, That he have leave to bring in a Bill intituled “ A Bill relating to Riot Damages and for other purposes.” 4. Mr. Pollard : To move, That he have leave to bring in a Bill intituled “ A Bill to amend the ‘ Local Government Act 1915 ’ and for other purposes.” 5. Mr. Old : To move, That he have leave to bring in a Bill intituled “ A Bill to provide for the Registration of Packing Sheds and for other purposes in connexion with the Dried Fruits Industry.” 6. -

Aspects of the Victorian Parliament at the Exhibition Building, 1901 to 1927

Parliament in Exile: Aspects of the Victorian Parliament at the Exhibition Building, 1901 to 1927 Victor Isaacs * For 26 years the Victorian Parliament met in the Exhibition Building in Melbourne whilst the Commonwealth Parliament temporarily occupied Parliament House in Spring Street. Especially during the early years the Victorians protested periodically about the arrangement and for a brief period returned to their own building. Much of the discontent centred on access to and use of the Library. The Federal Parliament occupied the Victorian State Parliament House at Spring Street from 1901 to 1927. Various political histories of the Commonwealth have examined Federal occupation of this building. 1 This article, however, examines the impact on the Victorian Parliament. These included an attempt by the Victorians not to leave their home, but to have the Commonwealth Parliament occupy the Exhibition Building, and an attempt by the State to occupy the Spring Street building simultaneously with the Commonwealth Parliament. The Commonwealth’s choice There was no mention of the site of the future Federal capital in the draft Federal Constitution submitted to colonial electors for approval in the 1898 referenda, and this was one of the factors leading to the failure of the referendum in New South Wales. Consequently, a Premiers’ Conference of 1899 settled this and some other contentious questions. The revised draft Constitution, in section 125, now provided that the future federal capital would be in territory granted by New South Wales, and that ‘The Parliament shall sit at Melbourne until it meet at the seat of Government.’ Both New South Welsh and Victorian honour was satisfied. -

The Royal Regiment of Scotland a Soldier's Handbook

The Royal Regiment of Scotland SCOTS A Soldier’s Handbook Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Colonel in Chief The Royal Regiment of Scotland Contents Section Page Introduction 3 The Structure of the Regiment 3 Uniform 7 Regimental Miscellany 12 History Part One 19 History Part Two 25 History Part Three 30 Victoria Crosses 36 Values and Standards of the British Army 40 List of Illustrations Colour Sergeant on Parade Cover The Colonel in Chief 1 Regimental Headquarters 3 On Patrol in Afghanistan 4 Training in Belize, Central America 5 Afghanistan 2006 6 Capbadge and Tactical Recognition Flash 7 Hackles 8 Number 1 Dress Ceremonial 9 Jocks in Action 11 The Military Band 12 Remembrance Day Baghdad 13 Piper in Iraq 14 Air Assault 15 The Golden Lions Scottish Infantry Parachute Display Team 16 The Regimental Kirk 17 Regimental Family Tree 18 A Soldier of Hepburn’s Regiment 1633 19 A Grenadier of Hepburn’s Regiment at Tangier 1680 20 Crawford’s Highlanders at Fontenoy 21 Battle of Ticonderoga 21 Battle of Minden 22 The Duke of Wellington 23 The Duchess of Gordon 24 Piper Kenneth Mackay 25 The Troopship Birkenhead 26 The Thin Red Line 27 William McBean VC 28 Winston Churchill 30 Robert McBeath VC 31 Dennis Donnini VC 32 William Speakman VC 33 Armoured Infantry in Iraq 35 Regimental Capbadge Back Cover 2 The Royal Regiment of Scotland INTRODUCTION The Royal Regiment of Scotland is Scotland’s Infantry Regiment. Structured, equipped and manned for the 21st Century, we are fiercely proud of our heritage. Scotland has a tradition of producing courageous, resilient, tenacious and tough, infantry soldiers of world renown. -

A History of Victorian Public Service Unionism 1885-1946

From Servants to Citizens: A History of Victorian Public Service Unionism 1885-1946 Dustin Raffaele Halse Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne Institute for Social Research Swinburne University of Technology 2015 Abstract The history of Victorian departmental public service unionism had its genesis in the era of ‘New Unionism’ in the 1880s. On 17 June 1885, a group of approximately 1,000 Victorian public servants packed into Melbourne’s Athenaeum Theatre to create Australia’s first state departmental public service union. And yet despite its age, Victorian departmental public service unionism has seldom been the subject of serious historical analysis. It has alternatively been posited that public servants are devoid of the ‘bonds of class feelings’. Public servants have commonly been treated as a residual class in both Marxist and non-Marxist labour history writings. This dissertation therefore fills an obvious lacuna in Australian trade union historiography. It focuses on the experiences of ordinary Victorian public service unionists and the actions of the various configurations of Victorian service unionism from 1885-1946. The central argument of this history is that public service unionists, with the aid of the public service union, challenged the theoretical and practical limitations placed upon their political and industrial citizenship. Indeed, public servants refused to accept the traditional ‘servant’ stereotype. Throughout this dissertation the regulations governing the unique employment status of public servants are revealed. What becomes evident is that public service unionists are frequently subjected to extreme levels of political coercion as a direct result of the historical influence of the master and servant legacy. -

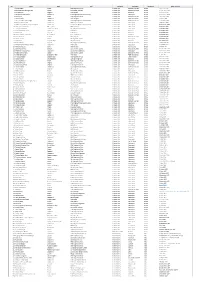

Nr1 Name Rank Unit Campaign Campaign. Campaign.. Date Of

Nr1 Name Rank Unit Campaign Campaign. Campaign.. Date of action 1 Thomas Beach Private 55th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 2 Edward William Derrington Bell Captain Royal Welch Fusiliers Crimean War Battle of the Alma Crimea 20 September 1854 3 John Berryman Sergeant 17th Lancers Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 4 Claude Thomas Bourchier Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 20 November 1854 5 John Byrne Private 68th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 6 John Bythesea Lieutenant HMS Arrogant Crimean War Ã…land Islands Finland 9 August 1854 7 The Hon. Clifford Henry Hugh Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 8 John Augustus Conolly Lieutenant 49th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 26 October 1854 9 William James Montgomery Cuninghame Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 20 November 1854 10 Edward St. John Daniel Midshipman HMS Diamond Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 18 October 1854 11 Collingwood Dickson Lieutenant-Colonel Royal Regiment of Artillery Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 17 October 1854 12 Alexander Roberts Dunn Lieutenant 11th Hussars Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 13 John Farrell Sergeant 17th Lancers Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 14 Gerald Littlehales Goodlake Brevet Major Coldstream Guards Crimean War Inkerman Crimea 28 October 1854 15 James Gorman Seaman