Old School Aberthin Rd July 2019 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Gelli Garn Cottages, St Mary Hill Near Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF35 5DT

2 Gelli Garn Cottages, St Mary Hill Near Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF35 5DT 2 Gelli Garn Cottages, St Mary Hill Nr Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF35 5DT £450,000 Freehold 3 Bedrooms : 2 Bathrooms : 1 Reception Rooms Hall • Living room • Kitchen-breakfast room • Rear entrance porch • Ground floor shower room Three double bedrooms • Bathroom Generous gardens and grounds of about ¼ of an acre Garage • Driveway parking • Paved patio • Lawns EPC Rating: TBC Directions From Cowbridge proceed in a westerly direction along the A48 and at the first cross roads by the Hamlet of Pentre Meyrick turn right. Continue north along this road, passing Llangan School and carry on further for approximately half a mile turning left after Fferm Goch where indicated to St. Mary Hill. Travel along this lane for about half a mile, bearing left at the next junction. 2 Gelli Garn Cottages will be on your right after a further 300 yards, the first of a pair of semi detached homes. • Cowbridge 0.0 miles • Cardiff City Centre 0.0 miles • M4 (J35) 0.0 miles Your local office: Cowbridge T 01446 773500 E [email protected] Summary of Accommodation ABOUT THE PROPERTY * Traditional semi detached family home * Extended in recent years to create kitchen, ground floor shower room and additional bedroom space. * Large living room with double doors to south-facing front garden * Plenty for room for seating and also for a family sized dining table * Traditional kitchen with room for breakfast table. Electric oven, hob and integrated fridge all to remain * Ground floor shower room * Three double bedrooms and bathroom to the first floor * Principle bedroom with superb views in a southerly direction over farmland GARDENS AND GROUNDS * South facing, paved patio fronting the property accessed via double doors from the living room * Sheltered lawn * Gardens and grounds of close to 1/4 of an acre in total * Block paved, off-road parking for a number of cars * Detached, block built garage (approx. -

The City and County of Cardiff, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taff and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY AND COUNTY OF CARDIFF, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAFF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COMMITTEE AGENDA ITEM NO THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 21st May 2021 National Broadcast Archive REPORT OF: THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report updates members on the plans for the National Broadcast Archive to host a Clip Corner at Glamorgan Archives. 2. BACKGROUND As reported to previous Joint Committee meetings, the National Library of Wales has asked Glamorgan Archives to host a Clip Corner, which will allow material from the National Broadcast Archive to be shown on dedicated terminals in the building. It is planned that the Clip Corner will be located in the reception area at Glamorgan Archives and it will have a direct VPN link to the material (which includes BBC Wales, ITV Wales and S4C archive footage). NLW have requested that the agreement be in the form of a Lease. This resolves issues for them around the copyright of the material and its’ use at Glamorgan Archives. The Lease has not been appended to this report because of confidentiality reasons, but has been supplied to all Joint Committee members in advance. 3. LEGAL IMPLICATIONS The Glamorgan Archivist is appointed by the Committee to manage the joint archives service on behalf of the Committee; to exercise the duties powers and functions of the parties under the enactments agreements and instruments set out in the Joint Archives Committee agreement dated 11 April 2006; to comply with national standards for archive keeping; to satisfy the requirements of the National Assembly for Wales with regard to archive services; to provide the services agreed by the parties; and to develop such additional services as may be appropriate. -

Newsletter 16

Number 16 March 2019 Price £6.00 Welcome to the 16th edition of the Welsh Stone Forum May 11th: C12th-C19th stonework of the lower Teifi Newsletter. Many thanks to everyone who contributed to Valley this edition of the Newsletter, to the 2018 field programme, Leader: Tim Palmer and the planning of the 2019 programme. Meet:Meet 11.00am, Llandygwydd. (SN 240 436), off the A484 between Newcastle Emlyn and Cardigan Subscriptions We will examine a variety of local and foreign stones, If you have not paid your subscription for 2019, please not all of which are understood. The first stop will be the forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew.haycock@ demolished church (with standing font) at the meeting museumwales.ac.uk). If you are able to do this via a bank point. We will then move to the Friends of Friendless transfer then this is very helpful. Churches church at Manordeifi (SN 229 432), assuming repairs following this winter’s flooding have been Data Protection completed. Lunch will be at St Dogmael’s cafe and Museum (SN 164 459), including a trip to a nearby farm to Last year we asked you to complete a form to update see the substantial collection of medieval stonework from the information that we hold about you. This is so we the mid C20th excavations which have not previously comply with data protection legislation (GDPR, General been on show. The final stop will be the C19th church Data Protection Regulations). If any of your details (e.g. with incorporated medieval doorway at Meline (SN 118 address or e-mail) have changed please contact us so we 387), a new Friends of Friendless Churches listing. -

Church Cottage, Aberthin, Vale of Glamorgan, Cf71 7Ld

CHURCH COTTAGE, ABERTHIN LANE, ABERTHIN, VALE OF GLAMORGAN, CF71 7LD CHURCH COTTAGE, ABERTHIN, VALE OF GLAMORGAN, CF71 7LD A CHARACTERFUL COTTAGE HAVING CONSIDERABLE POTENTIAL WITH ADJOINING PADDOCK OF ABOUT 2.4 ACRE Cowbridge 1.2 miles Cardiff City Centre 12.6 miles M4 (J34) 7.5 miles Accommodation and amenities: Lounge • Sitting Room / Bedroom 3 • Kitchen- Dinign Room • Cloakroom • Ground Floor Bathroom Two Bedrooms to First Floor Gardens • Outbuildings Paddock of about 2.4 acre EPC Rating: E Chartered Surveyors, Auctioneers and Estate Agents 55 High Street, Cowbridge, Vale Of Glamorgan, CF71 7AE Tel: 01446 773500 Email: [email protected] www.wattsandmorgan.co.uk www.wattsandmorgan.co.uk SITUATION The Village of Aberthin includes a combination of stone-built Cottages and houses together with more modern properties and is surrounded by farmland and the adjoining Stalling Down Common which allows pleasant walks. The Village also includes two public houses and a Village Hall. The nearby Market Town of Cowbridge has a range of shops and services to suit all needs. There are well regarded local Primary and Secondary Schools in addition to a public library, health centre and Old Hall Community Centre. Recreation facilities include a leisure centre and various sporting clubs, which offer tennis, squash, cricket, rugby, football and bowls. Cowbridge lies some 13 miles west of Cardiff which has the usual amenities of a Capital City including a main-line rail connection to London in around two hours. The area is serviced by the A48 which by- passes the Town along the route from Cardiff to Bridgend and Swansea. -

Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE

These minutes are subject to approval as an accurate record at the next meeting of the Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE Minutes of the Meeting of the Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee held at Glamorgan Archives, Leckwith, Cardiff on Friday 16 September 2011 at 2.00pm. Present: Members Representing: Vale of Glamorgan County Borough Council County Councillors A D Hampton and A M Ernest Cardiff County Council County Councillors J Cowan, , R Jerrett, J Parry & A Robson Caerphilly County Borough Council County Councillor Criddle Rhondda Cynon Taff County Borough Council County Councillors John David, E Jenkins, R. Bevan Officers in Attendance: Miss S Edwards, Glamorgan Archivist Mrs Charlotte Hodgson, Deputy Glamorgan Archivist Mr Marc Falconer, Operational Manager (Projects Accountancy), Cardiff County Council Mr Stephen Ham, Solicitor, Cardiff County Council Ms Joanne Jones, Information Officer, Caerphilly County Council Mrs Andrea Redmond, Committee and Members Services, Cardiff County Council 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from: County Councillor M Butcher, Bridgend County Borough Council County Councillor J Hooper, Cardiff County Council Page 1 of 15 These minutes are subject to approval as an accurate record at the next meeting of the Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee Ms Kate Thomas, The Lord Lieutenant Mr McLaggan 2. DECLARATION OF INTEREST Members had no declarations of personal interest in matters pertaining to the agenda. 3. MINUTES RESOLVED – That the minutes of the meeting of the Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee 17 June 2011 were approved as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. 4. MATTERS ARISING Members discussed the Open Doors Project. -

1874 Marriages by Groom Glamorgan Gazette

Marriages by Groom taken from Glamorgan Gazette 1874 Groom's Groom's First Bride's Bride's First Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname Name/s Surname Name/s Marriage Newspaper Bailey Alfred Davies Selina 30/05/1874 Register Office Groom coity Bride Coity 05/06/1874 2 3 Baker Samuel Williams Hannah 28/3/1874 Bettws Church Groom - Coytrahen 3/4/1874 2 6 Row, Bride of Shwt. Bevan Jenkin Marandaz Mary 17/12/1874 Margam Groom son of Evan 18/12/1874 2 5 Bevan Trebryn Both of Aberavon Bevan John Williams Ann 15/11/1874 Parish Church Pyle Both of Kenfig Hill 04/12/1874 2 5 Blamsy Arthur Wills Sarah 30/17/1874 Wesleyan chapel Groom of H M Dockyard 14/08/1874 2 6 Bridgend Portsmouth Bride Schoolmistress of Porthcawl Brodgen James Beete Mary Caroline 26/11/1874 Ewenny Abbey Groom Tondu House 27/11/1874 2 7 Church Bridgend and 101 Gloucester Place Portman Square London Bride Only daughter of Major J Picton Beete Brooke Thomas david Jones Mary Jane 28/04/1874 Gillingham Kent Groom 2nd son of 08/05/1874 2 5 James Brook Bridgend Bride elder daughter of John Jones Calderwood Marandaz 28/04/1874 Aberavon Groom Draper Bride 01/05/1874 2 7 Bridge House Aberavon Groom's Groom's First Bride's Bride's First Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname Name/s Surname Name/s Marriage Newspaper Carhonell Francis R Ludlow Catherine 13/02/1874 Christchurch Clifton Groom from Usk 20/02/1874 2 4 Dorinda Monmouth - Bride was Daughter of Rev A R Ludlow Dimlands Castle Llantwit Major Carter Edmund Shepherd Mary Anne -

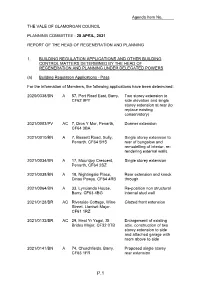

Planning Committee Report 20-04-21

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 28 APRIL, 2021 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2020/0338/BN A 57, Port Road East, Barry. Two storey extension to CF62 9PY side elevation and single storey extension at rear (to replace existing conservatory) 2021/0003/PV AC 7, Dros Y Mor, Penarth, Dormer extension CF64 3BA 2021/0010/BN A 7, Bassett Road, Sully, Single storey extension to Penarth. CF64 5HS rear of bungalow and remodelling of interior, re- rendering external walls. 2021/0034/BN A 17, Mountjoy Crescent, Single storey extension Penarth, CF64 2SZ 2021/0038/BN A 18, Nightingale Place, Rear extension and knock Dinas Powys. CF64 4RB through 2021/0064/BN A 33, Lyncianda House, Re-position non structural Barry. CF63 4BG internal stud wall 2021/0128/BR AC Riverside Cottage, Wine Glazed front extension Street, Llantwit Major. CF61 1RZ 2021/0132/BR AC 29, Heol Yr Ysgol, St Enlargement of existing Brides Major, CF32 0TB attic, construction of two storey extension to side and attached garage with room above to side 2021/0141/BN A 74, Churchfields, Barry. Proposed single storey CF63 1FR rear extension P.1 2021/0145/BN A 11, Archer Road, Penarth, Loft conversion and new CF64 3HW fibre slate roof 2021/0146/BN A 30, Heath Avenue, Replace existing beam Penarth. -

Kings Hall, Wick Road, St. Brides Major, CF32 0SE

Kings Hall, Wick Road, St. Brides Major, CF32 0SE £775,000 Freehold pablack.co.uk Cowbridge - PA Black 01446 772857 Kings Hall, Wick Road, St. Brides Major, CF32 0SE A truly magnificent 17th century detached six bedroom Entrance Reception Hall former farm house, built with solid stone and listed as a County Treasure in a conservation area modernised in Approached by a magnificent porch, solid wood recent years and boasting an outstanding south facing panelled front entrance door, leading to a central hall 1/2 acre level garden and backing onto open fields. with flagstone flooring, wood beams, a mixture of stone and plaster walls. Returning staircase with spindle balustrade leading to a half landing and inner landing, Positioned on the edge of the Historic Village of St Brides open gallery landing. Door to living room and door into the family / breakfast room. Major, just 15 minutes' drive from junctions 35 and 36 off the M4, this capacious residence of character includes Family Room considerable period features, including a charming entrance reception hall with a gallery landing, 23' 4" max x 17' 4" max ( 7.11m max x 5.28m max ) approached by an imposing solid wood panelled front Flagstone flooring, wood beams, a mixture of stone and entrance door, leading to a wide hall with flagstone plaster walls and an open fireplace with a wood burner. Window with outlooks across the private enclosed front floors. garden, and further two picture windows to the rear of the property. The family room is currently being used as a formal dining room. -

WELSH ST DONATS COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES of COMMUNITY COUNCIL MEETING on 1St December 2015

WELSH ST DONATS COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES OF COMMUNITY COUNCIL MEETING ON 1st December 2015 PRESENT: Councillors Andrew Foyle (in the Chair), Ann Thomas, Peter Castle and Graham Duffield, Rhodri Traherne. Members of the public: Christine Evans, Roger Helliwell ITEM 1 (636) PUBLIC FORUM Roger Helliwell was concerned about the absence and condition of existing footway to Cowbridge from Ystradowen. Rhodri confirmed that the 106 agreement through the Edenbrook development in Ystradowen would provide funds to complete the footway. Problems with overhanging branches and the condition of the existing footway should be reported to the Vale through the Clerk. Christine Evans reported that Christmas Celebrations at Hendrewennol had been cancelled and the covers on the poly tunnels had not all been removed, as advised in the planning approval notice. Clerk to report to Enforcement Unit. ITEM 2 (637) RECEIVE APOLOGIES Bill Fawcett, Glyn Jenkins, Nick Craddock and PCSO Kieran Byrne . ITEM 3 (638) DECLARATION OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS Andrew Foyle declared an interest in the planning application for Maendy Ganol, completed a pro forma and left the meeting for any discussions concerning this application. ITEM 4 (639) The minutes of the meeting on 3rd November 2015 were approved and signed. ITEM 5 (640) POLICE REPORT There were no recorded crimes in the area in November ITEM 6 (624) MATTERS ARISING The working party at the pond had been successful and thanks go to everyone who helped out. ITEM 7 (641) REPORT FROM RHODRI TRAHERNE Police: Rhodri would be meeting Alun Michael, Police Commissioner and asked for any issues Councillors would like raised Hendrewennol: Rhodri explained the complexity of the situation involving several Council Departments and included establishing a historical perspective. -

Former Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee

Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee Statement of Accounts 2012/2013 Glamorgan Archives Statement of Accounts 2012/2013 Page 1 of 39 Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee Statement of Accounts 2012/2013 Contents Page Introduction 3 Summary of Financial Performance 2012/2013 4 Guide to the Financial Statements 8 Statement of Accounting Policies 10 Critical Assumptions in Applying Accounting Policies 14 Statement of Responsibilities for the Statement of Accounts 15 Certificate of the Interim Section 151 Officer 16 Comprehensive Income & Expenditure Statement 17 Movement in Reserves Statement 18 Balance Sheet 19 Cashflow Statement 20 Notes to the Core Financial Statements 21 Annual Governance Statement 32 Certification by the Chair of Committee & Archivist 37 Independent Auditor’s Report 38 Page 2 of 39 Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee Statement of Accounts 2012/2013 Explanatory Foreword 1. Introduction This document presents the Statement of Accounts for the Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee. These are prepared on a going concern basis in accordance with proper accounting practices as contained in the Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the United Kingdom 2012/13 and supported by International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). This is the third year that the Statement of Accounts has been prepared on an IFRS basis, the Joint Committee having adopted the IFRS-based Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the United Kingdom. Adoption of this Code has had no impact on the financial contributions required from the Member Authorities to fund the Glamorgan Archives Joint Committee. Glamorgan Archives collects, preserves and makes accessible to the public, documents relating to the area it serves, and maintains the corporate memory of its constituent Local Authorities. -

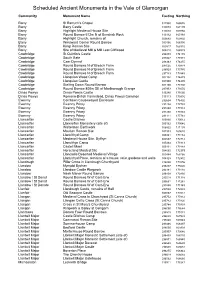

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan Community Monument Name Easting Northing Barry St Barruch's Chapel 311930 166676 Barry Barry Castle 310078 167195 Barry Highlight Medieval House Site 310040 169750 Barry Round Barrow 612m N of Bendrick Rock 313132 167393 Barry Highlight Church, remains of 309682 169892 Barry Westward Corner Round Barrow 309166 166900 Barry Knap Roman Site 309917 166510 Barry Site of Medieval Mill & Mill Leat Cliffwood 308810 166919 Cowbridge St Quintin's Castle 298899 174170 Cowbridge South Gate 299327 174574 Cowbridge Caer Dynnaf 298363 174255 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297025 173874 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 296929 173780 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297133 173849 Cowbridge Llanquian Wood Camp 302152 174479 Cowbridge Llanquian Castle 301900 174405 Cowbridge Stalling Down Round Barrow 301165 174900 Cowbridge Round Barrow 800m SE of Marlborough Grange 297953 173070 Dinas Powys Dinas Powys Castle 315280 171630 Dinas Powys Romano-British Farmstead, Dinas Powys Common 315113 170936 Ewenny Corntown Causewayed Enclosure 292604 176402 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291294 177788 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291260 177814 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291200 177832 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291111 177761 Llancarfan Castle Ditches 305890 170012 Llancarfan Llancarfan Monastery (site of) 305162 170046 Llancarfan Walterston Earthwork 306822 171193 Llancarfan Moulton Roman Site 307383 169610 Llancarfan Llantrithyd Camp 303861 173184 Llancarfan Medieval House Site, Dyffryn 304537 172712 Llancarfan Llanvithyn -

Helpful Information for Life at the College Contents HELPFUL INFORMATION Why You Are Coming to Theuk

WELCOME Helpful information for life at the college Contents If you have been successful in your application, here is some helpful information about making sure your arrival at the College is as smooth as possible. HELPFUL INFORMATION HELPFUL Good luck from us all at UWC Atlantic - we look forward to working with you! Arrival in the UK Your job offer from the College will be on the condition the relevant papers which allow you to stay and work in the that you can prove you have permission to live and work UK. It would be helpful to have the following items in your in the UK. It is therefore essential to ensure that you have hand luggage: gained your Visa and relevant documentation prior to • Job offer travelling to the UK. For further guidance on completing your immigration application please see the UK Visas and • Degree certificates Immigration website or contact [email protected] • Reference letter from your bank to help you set up a If you are not a citizen of the EEA or Switzerland, you will bank account in the local area need to complete a landing card immediately upon your • Driving licence arrival at the UK border and before you proceed to the passport desks. You will need to write down your personal You might want to have a photocopy of the main parts of details and your UK contact address on the landing card. your passport and the copies of essential documents in your main luggage, together with your clothes, toiletries, At the passport desk, the immigration officer will look at electrical goods (including a UK power adaptor) and your passport and visas take your landing card and ask you personal items.