In Search of a Citizenship Education Model for a Democratic Multireligious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baso Maruddani - Haki - C.6 .1

METODE PREDIKSI DAN TEKNIK MITIGASI REDAMAN PROPAGASI HUJAN MENGUNAKAN HIDDEN MARKOV MODEL PADA KANAL SATELIT PITA-K DI DAERAH TROPIS DISERTASI Karya tulis sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Doktor dari Institut Teknologi Bandung Oleh Baso Maruddani NIM : 33207303 (Program Studi Teknik Elektro dan Informatika) INSTITUT TEKNOLOGI BANDUNG 2013 ABSTRAK METODE PREDIKSI DAN TEKNIK MITIGASI REDAMAN PROPAGASI HUJAN MENGUNAKAN HIDDEN MARKOV MODEL PADA KANAL SATELIT PITA-K DI DAERAH TROPIS Oleh Baso Maruddani NIM : 33207303 Redaman propagasi hujan pada frekuensi pita-K sangat tinggi. Dimensi panjang gelombang pada frekuensi pita-K yang mendekati ukuran butir hujan menyebabkan kuat sinyal pada frekuensi ini sangat mudah diredam oleh butiran hujan karena sinyal dengan mudah mengalami hamburan dan serapan oleh butiran hujan tersebut. Redaman oleh butiran hujan ini menjadi salah satu faktor terbesar yang menyebabkan level sinyal yang sampai di penerima tidak mencapai level sensitivitas penerima. Redaman propagasi akibat hujan merupakan faktor yang paling mempengaruhi pada sistem komunikasi satelit pita-K, terutama pada daerah dengan curah hujan yang tinggi. Evaluasi pengaruh dari redaman ini membutuhkan pengetahuan yang detil dari statistik redaman propagasi di setiap tempat dan pada rentang frekuensi tertentu. Redaman propagasi akibat hujan dipengaruhi oleh curah hujan yang terjadi di sepanjang lintasan antara satelit dengan lokasi tempat SB terpasang. Hujan terdistribusi ruang dan waktu sehingga setiap lokasi memiliki intensitas dan waktu hujan yang berbeda. Oleh karena itu diperlukan data yang memadai mengenai curah hujan untuk memprediksi redaman propagasi akibat hujan. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengembangkan sebuah metode prediksi kanal yang merepresentasikan redaman propagasi akibat hujan untuk frekuensi pita-K pada kanal komunikasi satelit dan mengembangkan algoritma teknik mitigasi redaman propagasi hujan yang efektif untuk mengatasi redaman propagasi akibat hujan untuk kanal komunikasi satelit di Indonesia. -

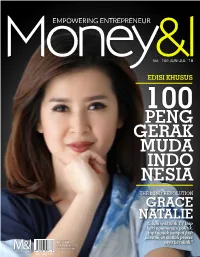

Peng Gerak Muda Indo Nesia

EMPOWERING ENTREPRENEUR MoneyVol.&I 100 JUN-JUL '18 EDISI KHUSUS 100 PENG GERAK MUDA INDO NESIA THE MIND REVOLUTION GRACE NATALIE “..dulu waktu di TV tiap hari ngomongin politik, tapi nggak sampai jadi passion, di sinilah proses Rp. 32.500 saya berubah.” WWW.MONEYINSIGHT.ID MONTHLY MAGAZINE MONEY&I MAGAZINE Vol. 100 | Jun - Jul 2018 1 ISSN: 2087-5975 2 Vol. 100 | Jun - Jul 2018 BIMCSiloam - Advertorial - dr Ary - Diabetes Melitus - May 2018.indd All Pages 5/17/2018 10:57:57 AM Vol. 100 | Jun - Jul 2018 3 BIMCSiloam - Advertorial - dr Ary - Diabetes Melitus - May 2018.indd All Pages 5/17/2018 10:57:57 AM FROM THE EDITOR Arif Rahman @arif_journal 100 COVER emula, ini adalah sebuah Foto oleh Ida Bagus Baruna Luhur pemikiran yang lahir untuk Desain oleh Sahal Putra mengedukasi masyarakat soal keuangan dan MONEY&I MAGAZINE S Akubank School juga kewirausahaan, mencoba ikut Jl. Dewi Madri III berkontribusi atas persoalan disekitar kita Denpasar - Bali T. +62 823 3996 4020 akan banyaknya kasus penipuan karena [email protected] masalah investasi, ataupun minimnya www.moneyinsight.id jumlah pebisnis di Indonesia. Yang kita sepenuhnya menyadari, jumlah wirausaha For advertising enquiries please yang banyak dan berkinerja baik, bisa send an email to : mengantarkan Indonesia menjadi Berawal dari kolom sejahtera. di koran harian Indah Kencana Putri [email protected] BERAWAL DARI KOLOM KORAN HARIAN M. 0823 3996 4020 Desak Putu Widyawati Ide kecil ini kemudian teraplikasi dalam tengah masyarakat. Sepanjang 100 [email protected] M. 0823 4112 7767 bentuk kolom di koran harian lokal Bali edisi kami terus merangkai cerita, Pos, dengan nama rubrik Money&You konsisten melakukan wawancara DISTRIBUTION SUPPORT Adi Setiawan di tahun 2007, diasuh oleh Alex P kepada para inspirator hebat negeri ini, [email protected] Chandra selaku penggagas. -

KIAT SUKSES DITERIMA DI PERGURUAN TINGGI NEGERI PILIHAN TAHUN 2019 Oleh : [email protected]

KIAT SUKSES DITERIMA DI PERGURUAN TINGGI NEGERI PILIHAN TAHUN 2019 Oleh : [email protected] Jangan baperlah, kenyataan menunjukkan menjadi peserta didik di SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta itu sesuatu sekali. Banyak keluarga yang bangga ketika salah satu keluarga mampu untuk menimba ilmu di Taman Bukitduri Tebet. Harus diakui 25 tahun terakhir SMAN 8 Jakarta sedemikian melegenda. Pertemuan keluarga, arisan bahkan konten-konten di media sosial berisi kebahagian saat anggota kelurga resmi menjadi keluarga besar SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta. Kemampuan SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta meramu bahan dasar bahkan bahan setengah jadi menjadi bahan jadi yang enak dipandang bahkan diberi banyak apresiasi membuat banyak sekolah competitor bertanya apa rahasia dibalik keberhasilan SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta ? Jangan kaget SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta, beberapa tahun terakhir adalah sekolah reguler, bukan sekolah unggulan seperti SMA MHT. SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta juga termasuk sekolah yang sama dengan 115 sekolah lain di Jakarta, mendapatkan dana BOS, sehingga tidak ada lagi pungutan apa pun di sekolah. Apa ada jurus-jurus jitu yang dipakai sehingga anak- anak Bukitduri sedemikian berbeda dikancah kompetisi anak SMA baik di lomba-lomba akademis, non akademis bahkan di kompetisi memperebutkan bangku kuliah di Perguruan Tinggi,…. Yaa salam,.. doa untuk para guru baik yang masih aktif atau yang sudah purnabakti, semoga berkah segala ilmu, dengan kesehatan dan kebahagiaan,.. aamiin. Setiap kelas X yang saya datangi dalam beberapa tahun terakhir, dan saya menanyakan : “Kenapa memilih masuk ke SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta ?”, selalu saja jawabannya adalah : agar bisa diterima di Perguruan Tinggi Favorit. Kenapa ? Karena SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta hingga hari ini menjadi pemasok terbanyak ke UI ITB di Provinsi DKI Jakarta. -

2050 Asia-Pacific Writing Competition 2019

Our World: 2050 Asia-Pacific Writing Competition 2019 Contents Secondary Schools Winner Don’t Face It - Change It Island School, Hong Kong Clarissa Ki 10 Runner-Up Together, We Can Nord Anglia International School Hong Kong Philine Kotanko 12 Tertiary Winner Youth Empowerment Shaping the Next 30 Years Ngee Ann Polytechnic, Singapore Jonas Ngoh 16 Runner-Up Do Whatever You Want to Shape the Future The University of Hong Kong Alvin Lam 18 Note: All essays have been reviewed for grammatical and typographical inconsistencies but otherwise appear in their original form. Asia-Pacific Writing Competition 2019 3 Contents Shortlist of Entrants: Secondary School (listed in alphabetical order by school name) Beaconhouse Sri Inai International School, Malaysia Cheryl Chow 22 Beaconhouse Sri Inai International School, Malaysia Teng Yee Shean 23 British International School Hanoi, Vietnam Quoc Thai Kieu 24 British International School Hanoi, Vietnam Valerie Lua 25 Canadian International School of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Janae Ng 26 Cedar Girls’ Secondary School, Singapore Kareena Kumar 27 Christian Alliance Cheng Wing Gee College, Hong Kong Chin Pok Khaw 28 Concordia International School Shanghai, China Sophia Cho 29 Concordia International School Shanghai, China Edith Wong 30 Fairview International School, Malaysia Nethra Kaner 31 Gateway College Colombo, Sri Lanka Joel Shankar 32 Hanoi-Amsterdam High School for the Gifted, Vietnam Chi Tran 33 4 King George V School, Hong Kong Andrea Lam 34 King George V School, Hong Kong Christine Tsoi 35 Lotus Valley International School, India Ritika Singhal 36 L.P. Savani Academy, India Sarvik Chaudhary 37 Methodist Girls’ School, Singapore Estelle Lim 38 Mount Maunganui Intermediate School, New Zealand Amaya Greene 39 Mount Maunganui Intermediate School, New Zealand Skye Shaw 40 Pacific American School, Taiwan Ray Chen 41 Raffles Girls’ School, Singapore Phylicia Goh 42 Raffles Girls’ School, Singapore Chloe Wong 43 Ravenswood School for Girls, Australia Emily Ra 44 St. -

SMAN 8 Jakarta School Brochure

ABOUT US VISION Founded in August 1, 1958, SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta is Creating high quality graduates in the aspects of well known for its highly competitive admission personality, academics and non-academics of process, achievements in science competitions such international standard as the National Science Olympiad, and an excellent performance of its students in the Indonesian public university entrance examination. The school has been ranked as one of the best high schools in the country for multiple times, and recently ranked 4th nationally and 2nd highest in Jakarta province based on the average score on National University Placement Test (UTBK) 2020. INTELLIGENT CONTACT US SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta RESILIENT Jalan Taman Bukit Duri Tebet Jakarta Selatan 12840 - Indonesia CARING Ph. 021-8295455, Fax. 021-8351782 Website: www.sman8jkt.sch.id Email: [email protected] MISSION Organizing learning activities that are interactive, inspirational, fun, challenging students to participate actively and creatively. SMAN 8 Organizing a learning system that encourages actualization of student competencies. Carrying out personality development activities JAKARTA that include faith and noble morals. Organizing interest and talent development activities based on needs and achievement- S C H O O L P R O F I L E oriented. Implement efficient, effective, transparent and accountable school governance. CURRICULUM COLLEGE SMAN 8 received Accreditation ‘A’ from the ACCEPTANCE National Accreditation Body/BAN. The school is using Indonesia National Curriculum 2013 that NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES lasts for 3 years (10th to 12th grade), in which sudents should enroll in specialization of natural Many of SMAN 8 Jakarta graduates study in sciences or social sciences from the 10th grade. -

Pendidikan Bela Negara Sebagai Upaya Peningkatan Nasionalisme Bangsa

Pendidikan Bela Negara Sebagai Upaya Peningkatan Nasionalisme Bangsa PROSIDING SEMINAR NASIONAL PENDIDIKAN BELA NEGARA “Bela Negara Untuk Generasi Millenial ” Diselenggarakan Oleh PGSD FKIP UNIVERSITAS MURIA KUDUS KUDUS, 4 Maret 2020 BADAN PENERBIT UNIVERSITAS MURIA KUDUS TAHUN 2020 Pendidikan Bela Negara Sebagai Upaya Peningkatan Nasionalisme Bangsa PROSIDING SEMINAR NASIONAL PENDIDIKAN BELA NEGARA “Bela Negara Untuk Generasi Millenial ” Reviewer 1. Dr. Erik Aditia Ismaya, S.Pd., M.A. 2. Sekar Dwi Ardianti, S. Pd ., M.Pd. Editor : Dr. Erik Aditia Ismaya, S.Pd., M.A. Layouter : Much. Arsyad Fardhani, S.Pd., M.Pd. Hak Cipta Dilindungi Undang-undang Copyright@2020 ISBN : 978-623-7312-35-2 Penerbit Badan Penerbit Universitas Muria Kudus Alamat Penerbit Gondangmanis, Bae, Kudus PO. BOX 53 Kode Pos 59327 Jawa Tengah – Indonesia Telp.: 0291-438229 Fax : 0291-437198 Email : [email protected] SAMBUTAN KETUA PANITIA Puji dan syukur kehadirat Tuhan Yang Maha Esa karena atas karuniaNya Prosiding Seminar Nasional Pendidikan Bela Negara dengan tema “Bela Negara untuk Generasi Milenial” dapat diterbitkan. Seminar ini diselenggarakan oleh Program Studi Pendidikan Guru Sekolah Dasar Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Universitas Muria Kudus pada Rabu 4 Maret 2020 di Hotel @hom Kudus. Prosiding ini berisi kumpulan makalah dari pemakalah yang berasal dari beberapa perguruan tinggi di Indonesia serta telah dipresentasikan dan didiskusikan pada sesi paralel seminar. Seminar Nasional Pendidikan Bela Negara diselenggarakan untuk membuka wawasan dan pemahaman tentang bela negara yang merupakan kewajiban bagi seluruh warga negara Indoesia tanpa terkecuali para generasi millenial. Seminar ini juga memberikan kesempatan bagi para pemakalah yang merupakan akademisi dan praktisi untuk mendiseminasikan hasil-hasil penelitian atau kajian kritis terhadap pendidikan pada umumnya dan bela negara pada khususnya. -

Kata Pengantar

Laporan tahunan LPPM 2015 Kata Pengantar Puji dan syukur kepada Tuhan yang Maha pengasih karena kami dapat menyelesaikan tugas kami di tahun 2015 dengan baik, sehingga Laporan Tahunan ini juga dapat diselesaikan. Sebagaimana pada tahun-tahun sebelumnya, Laporan Tahunan ini disajikan untuk menyampaikan seluruh kegiatan penelitian dan pengabdian kepada masyarakat yang telah dilaksanakan oleh tenaga pendidik di program studi/fakultas/unit yang ada lingkungan Unika Atma Jaya di bawah koordinasi LPPM Unika Atma Jaya. Laporan Tahunan ini akan terpusat pada empat butir sasaran mutu yang telah ditetapkan untuk LPPM pada tahun 2015, yaitu kinerja di bidang penelitian, kegiatan pengabdian kepada masyarakat, pertemuan/kegiatan ilmiah yang diselenggarakan, dan publikasi karya ilmiah ditingkat nasional maupun internasional. Laporan tahunan LPPM 2015 Laporan tahunan LPPM 2015 I. ORGANISASI LPPM 1.1. Latar Belakang Mengacu pada SK Yayasan Atma Jaya No. 006/I/SK/01/97, maka tertanggal 1 Februari 1997 didirikanlah Lembaga Penelitian Atma Jaya (LPA) dan Lembaga Pengabdian Masyarakat (LPM), dan masing-masing Lembaga dipimpin oleh seorang Ketua. Pada tahun 2007 kedua lembaga tersebut dilebur menjadi satu dengan nama Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarkat (LPPM), yang dipimpin oleh seorang Ketua. Penggabungan LPA dan LPM menjadi LPPM ditegaskan dalam Statuta Unika Atma Jaya. Secara keorganisasian LPPM berada di bawah Rektor. Pada Bab VIII Pasal 30 statuta tersebut, diuraikan bahwa LPPM adalah unsur pelaksana tridarma perguruan tinggi yang melaksanakan sebagian tugas pokok dan fungsi universitas untuk darma penelitian dan pengabdian kepada masyarakat. Tugas pokok dari LPPM adalah melaksanakan, mengkoordinasikan, dan memantau pelaksanan kegiatan penelitian dan pengabdian kepada masyarakat, yang diselenggarakan oleh staf pendidik secara individual atau berkelompok, program studi, fakultas, atau unit organisasi yang berada di bawah Universitas. -

Watermark LAPORAN AKADEMIK HANYA PRESTASI

PROFIL SMA NEGERI 8 JAKARTA 1.IDENTITAS SEKOLAH Nama : SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta NSS/NIS : 30101630100 / 30081 NPSN : 20102568 Kepala sekolah : Drs. Agusman Anwar Alamat : Jalan Taman Bukitduri, Tebet, Jakarta Selatan Kode pos 12840 Telephon : (021) 8295455 Fax : (c)(021) 8351782 Website : http://www.sman8jkt.sch.id Email : [email protected] Visi Menjadi SMA bertaraf International yang memiliki keseimbangan dalam pembinaan akademis dan kepribadian Misi Menyelenggarakan kegiatan pembelajaran yang bersifat interaktif, inspiratif, menyenangkan menantang peserta didik untuk berpartisipasi secara aktif dan kreatif Melaksanakan kegiatan pembinaan kepribadian yang meliputi keimanan dan akhlak mulia Menyelanggarakan kegiatan pengembangan minat dan bakat berbasis kebutuhan dan berorientasi pada prestasi Melaksanakan tata kelola sekolah efisien, efektif, transparan serta dapat dipertanggung jawabkan PrestasiSijambro Sekolah UJIAN NASIONAL ng yaa Rekapitulasi Medali Olimpiade Sains Nasional SMA NEGERI 8 JAKARTA Olimpiade Sains Nasional 2018 1. Daffa Fathani Meraih Medali Emas bidang Fisika 2. Antonius Berwin Meraih Medali Perak bidang Astronomi 3. Shafira Aurelia Meraih Medali Perak bidang Fisika 4. Ghayda Nafisa Assakura Meraih Medali Perak bidang Biologi 5. Jessica Annabel Meraih Medali Perak bidang Ekonomi 6. Ubaidillah Ariq Meraih Medali Perunggu bidang Matematika 7. Tivano Antoni(c) Meraih Medali Perunggu bidang Kimia 8. Muhammad Nabiel Meraih Medali Perunggu bidang Astronomi Olimpiade Sains Nasional 2017 1. Prawira Satya Darma Meraih Medali -

Brochure S1 2-16.Cdr

Admission Regular Program - applicable for Indonesian passport holder Bachelor of Management and Bachelor of Entrepreneurship Starng in 2013, ITB only accepts admission for undergraduate program through SNMPTN(Non-test Track) and SBMPTN (Wrien Test Track). Prospecve students from highly respected schools intending to connue their studies, please enroll through SNMPTN and/or SBMPTN. Undergraduate Program SNMPTN School of Business and Management hp://snmptn.ac.id/ Institut Teknologi Bandung SBMPTN hp://sbmptn.ac.id/ In SNMPTN, students must be from IPA or IPS class and join collecve registraon through appointed his/her high school representave. In SBMPTN, SBM ITB is classified in IPS (Social) wrien test track. Students must be from IPA or IPS class. Below are the subjects to be tested: Basic Subjects : Matemaka Dasar, Bahasa Indonesia, dan Bahasa Inggris. Social Subjects: Sosiologi, Sejarah, Ekonomi, Geografi. Details about ITB regulaon on SNMPTN and SBMPTN, please refer to www.usm.itb.ac.id. Applicants are suggested to check SBM ITB official website (www.sbm.itb.ac.id) regularly to get updates. Internaonal Program - applicable for Indonesian passport holder and Non-Indonesian passport holder Bachelor of Management in Internaonal Business Program Starng in 2016, ITB open enrollment through internaonal class admission track. Prospecve students from highly respected schools intending to connue their studies, please enroll through this track and follow the procedure. Every admission process must follow the procedure in www.usm.itb.ac.id. Applicants are suggested to check SBM ITB official website (www.sbm.itb.ac.id) regularly to get updates. Prospecve students must meet the following requirements: Ÿ Have good English language skills, proven by one of the English language proficiency cerficates. -

Brochure S1 ABEST 21.Cdr

Admission Regular Program - applicable for Indonesian passport holder Bachelor of Management and Bachelor of Entrepreneurship Starting in 2013, ITB only accepts admission for undergraduate program through SNMPTN(Non-test Track) and SBMPTN (Written Test Track). Prospective students from highly respected schools intending to continue their studies, please enroll through SNMPTN and/or SBMPTN. Undergraduate Program SNMPTN School of Business and Management http://snmptn.ac.id/ Institut Teknologi Bandung SBMPTN http://sbmptn.ac.id/ In SNMPTN, students must be from IPA or IPS class and join collective registration through appointed his/her high school representative. In SBMPTN, SBM ITB is classified in IPS (Social) written test track. Students must be from IPA or IPS class. Below are the subjects to be tested: Basic Subjects : Matematika Dasar, Bahasa Indonesia, dan Bahasa Inggris. Social Subjects: Sosiologi, Sejarah, Ekonomi, Geografi. Details about ITB regulation on SNMPTN and SBMPTN, please refer to www.usm.itb.ac.id. Applicants are suggested to check SBM ITB official website (www.sbm.itb.ac.id) regularly to get updates. International Program - applicable for Indonesian passport holder and Non-Indonesian passport holder Bachelor of Management in International Business Program Starting in 2016, ITB open enrollment through international class admission track. Prospective students from highly respected schools intending to continue their studies, please enroll through this track and follow the procedure. Every admission process must follow the procedure in www.usm.itb.ac.id. Applicants are suggested to check SBM ITB official website (www.sbm.itb.ac.id) regularly to get updates. Prospective students must meet the following requirements: Ÿ Have good English language skills, proven by one of the English language proficiency certificates. -

School Profile - SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta

School Profile - SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta About SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta is 3-year a public high school in South Jakarta, Indonesia. It is located on Jalan Taman Bukit Duri, South Jakarta. The school received Accreditation ‘A’ from National Accreditation Board (BAN). Founded in August 1, 1958, SMA Negeri 8 Jakarta is well known for its highly competitive admission process, achievements in science competitions such as the National Science Olympiad, and an excellent performance of its students in the Indonesian public university entrance examination. The school has been ranked as one of the best high schools in the country for multiple times, and recently ranked 4th nationally and 2nd highest in Jakarta province based on the average score on National University Placement Test (UTBK) 2020. Many of its students study in University of Indonesia and Bandung Institute of Technology, considered Indonesia's most prestigious colleges along with Gadjah Mada University, as well as universities abroad, many of them pursue degrees in medicine, engineering and economics. Vision Creating high quality graduates in the aspects of personality, academics and non-academics of international standard Mission • Organizing learning activities that are interactive, inspirational, fun, challenging students to participate actively and creatively. • Organizing a learning system that encourages actualization of student competencies. • Carrying out personality development activities that include faith and noble morals. • Organizing interest and talent development activities based on needs and achievement- oriented. • Implement efficient, effective, transparent and accountable school governance. Curriculum SMAN 8 received Accreditation ‘A’ from the National Accreditation Body/BAN. The school is using Indonesia National Curriculum 2013 that lasts for 3 years (10th to 12th grade) in which sudents should enroll in specialization of natural sciences or social sciences from the 10th grade. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 296 International Conference on Special and Inclusive Education (ICSIE 2018) A Review on Indonesia Policy in Supporting Gifted Students Education Robiansyah Setiawan Serafin Wisni Septiarti Yogyakarta State University Yogyakarta State University Yogyakarta, Indonesia Yogyakarta, Indonesia [email protected] and [email protected] Abstract— Generally, gifted students are known as students gifted students. This article will present the historical who have incredible ability in learning faster. The ability in landscape of education of gifted students in Indonesia during learning faster of gifted students which exceed their peer needs the last one decade. In relation to the history of education of special education services properly to avoid students being gifted students, the role of policy is examined as government underachiever. This article will present the definition, history support for the education of gifted students. In this and representation of how Indonesia government support education for gifted students in the last one decade. The opportunity, the reseachers will also examine what concerns development of gifted students in Indonesia is affected by the can occur to students’ academic abilities which are faster policy from Ministry of Education and Culture. This effect is than their peers and the alternative education that can be showed by the government policy by developing some new done for gifted students in Indonesia. programs and stopping the program for gifted students. The The rest of this paper is organized as follow: Section II concern of the negative impact on the potential gifted students describes the literature review.