Building the Revolutionary Party an Introduction to James P Cannon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarian Marxism Mao-Spontex Open Marxism Popular Assembly Sovereign Citizen Movement Spontaneism Sui Iuris

Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis Brian Marks1 University of Arizona School of Geography and Development [email protected] Abstract Autonomist Marxism is a political tendency premised on the autonomy of the proletariat. Working class autonomy is manifested in the self-activity of the working class independent of formal organizations and representations, the multiplicity of forms that struggles take, and the role of class composition in shaping the overall balance of power in capitalist societies, not least in the relationship of class struggles to the character of capitalist crises. Class composition analysis is applied here to narrate the recent history of capitalism leading up to the current crisis, giving particular attention to China and the United States. A global wave of struggles in the mid-2000s was constituitive of the kinds of working class responses to the crisis that unfolded in 2008-10. The circulation of those struggles and resultant trends of recomposition and/or decomposition are argued to be important factors in the balance of political forces across the varied geography of the present crisis. The whirlwind of crises and the autonomist perspective The whirlwind of crises (Marks, 2010) that swept the world in 2008, financial panic upon food crisis upon energy shock upon inflationary spiral, receded temporarily only to surge forward again, leaving us in a turbulent world, full of possibility and peril. Is this the end of Neoliberalism or its retrenchment? A new 1 Published under the Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis 468 New Deal or a new Great Depression? The end of American hegemony or the rise of an “imperialism with Chinese characteristics?” Or all of those at once? This paper brings the political tendency known as autonomist Marxism (H. -

Public Asked to Debate on Student Governm.Ent

1 Vol. XLl¥, No. ~ :2-'0 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C. Thursday, March 19, 1964 ~( Founclation Leacler Public Asked to Debate Announces Seniors Founders' Ceremony On Student Governm.ent Receiving "Wilsons" Will Present Degrees Sir Hugh Taylor, president The Philodemic Society is of the Woodrow Wilson Fel holding an open public debate lowship Foundation, has an tonight in Gaston Hall at 7 :30 nounced that five Georgetown on the status of the George seniors were appointed for town University student body first year graduate study next and its student government fall and three others were named concerning their failure "to con as alternates. tribute in full measure" to Uni The Georgetown winners are Ed versity life. ward P. Brynn, School of Foreign The text of the resolution, which Service; Edward B. Fallon, Larry was drafted by the Philodemic in F. Field, and Bruce M. Flattery, quiry committee led by Don Col College of Arts and Sciences; and leton (C '64) and will be read at James J. Lake, Institute of Lan the outset of this evening's session, guages and Linguistics. Those re reads as follows: ceiving honorable mention were "Whereas the Philodemic Debat Barbara A. Bitzer and Dorothy P. ing Society recognizes that it is Helm of the Institute, and Thomas the intention of the Administra M. Tebrow of the College. tion, the Faculty, and the Student Woodrow Wilson Fellowships Body to realize the full potential are awarded annually to under graduate students interested in MA YNARD HUTCHINS HYMAN G. RICK OVER DON COLLETON . of Georgetown University as one L of the great universities of the graduate studies and who ultimate II United States, and as America's ly wish to become college profes by John Kealy I] Student Mllg Assumes leading Catholic University; and sors. -

REVOLUTION Or WAR #10

REVOLUTION or WAR #10 Journal of the International Group of the Communist Left (IGCL) Biannual – September 2018 Summary The Rise of New Communist Forces and The Fight for The International Party International Situation Balance-sheet of Railworkers’ Defeat of Spring 2018 in France March 28th IGCL Leaflet for The Generalization and Unity of The Struggles May 10th Communique on The American Withdrawal from The Irani Nuclear Agreement Marxism and The National Question Correspondence What Relation between the International Party and Its Local Organizations? Debate within the Proletarian Camp What Is The Party? (Nuevo Curso) The Future International (Internationalist Communist Tendency) Some Comments on the ICT Text on the Future International History of the Working Class Movement Rosa Luxemburg and The Feminism (Nuevo Curso) E-mail : [email protected], website : www.igcl.org 4 dollars/3 euros Content (Our review is also available in French) The Rise of New Communist Forces and The Fight for The International Party..........................1 International Situation Balance-sheet of The Railway Workers’ Defeat of Spring 2018 in France........................................3 March 28th IGCL Leaflet for The Generalization and Unity of The Struggles..................................6 May 10th Communique on The American Withdrawal of The Irani Nuclear Agreement..............9 Marxism and The National Question............................................................................................................ 10 Correspondence What Relation -

Dobbs on Truckers Strike Rebecca Finch, New York Socialist Workers Party Candi in New York City

FEBRUARY 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38,1NUMBER 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE On-the-scene rel}orts Minnesota truckers vote Feb. 10 to continue strike. Reporters for the Militant aHended strike meetings around the country. For their reports, and special feature on Teamsters union and independent truckers in 1930s and today, see pages 5-9. riti m1ners• ae eat In Brief BERRIGAN REFUSED JOB AT ITHACA: 300 angry prisoners labeled "special offenders." students confronted Ithaca College President Henry Phillips Delegations from Rhode Island, Maine, and Connecti Feb. 7, demanding to know why the college withdrew an cut attended the rally, which was very spirited, despite offer of a visiting professorship to Father Daniel Berrigan. a heavy snowstorm. Speakers at the rally included Richard THIS The college made the offer last December and President Shapiro, executive director of the Prisoners Rights Project; Phillips withdrew it one month later without consulting Russell Carmichael of the New England Prisoners Associa students and faculty. tion; State Representative William Owens; and Jeanne Laf WEEK'S This was the second meeting called by students since ferty, Socialist Workers Party candidate for attorney gen a petition signed by 1,000 students failed to elicit a eral of Massachusetts. MILITANT response from the administration. The students are pro testing the arbitrary decision and demanding a full ex PUERTO RICAN POETRY FESTIVAL PLANNED: The 3 Union organizers speak planation for the withdrawal of the offer. Berrigan recently Committee for Puerto Rican Decolonization, an organiza out on fight of women criticized Israel's expansionist policies in the Mideast, which tion supporting the independence of Puerto Rico, is spon workers brought slanderous charges from pro-Zionist groups that soring a festival of Puerto Rican poetry. -

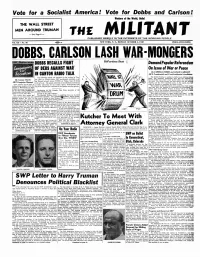

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

The Theory of the Cuban Revolution

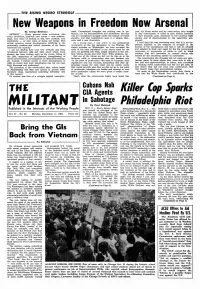

THE RISING NEGRO STRUGGLE New Weapons in Freedom Now Arsenal By George Breitman ment. Unemployed struggles are nothing new in our year. By direct action and by mass action, they sought DETROIT — Every genuine mass movement, like history, nor are demonstrations and picket lines. But this to stop construction in order to gain serious attention every revolution, produces new things — new relation was an unemployed struggle under the banner of racial to their demands (jobs, admission to the building trade ships, new ways of looking at life, new methods, new equality, and that combination gave it a unique char unions, end of discrimination in the apprentice pro institutions — or new ways of doing old things. This acter and a new dimension. grams) . article concerns recent developments testifying to the As a young man, I was active in the unemployed I hold that this was something new; that it is an im profoundly creative and radical character of the Negro movements of the big depression in the Thirties. We portant addition to the weapons of struggle in the movement for equality. staged marches on Washington, we once occupied the arsenal of the unemployed; and that it w ill be adopted I am not dealing here with new methods and ideas seats of the state legislators in m y native state fo r ten and adapted to their own needs by the big unemployed introduced between 1960 and 1962, about which much days, we picketed City Hall, staged sitdowns in the wel movement or movements of white as well as black already has been written, such as the sit-ins, filling of fare offices, struck and shut down WPA projects, etc. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

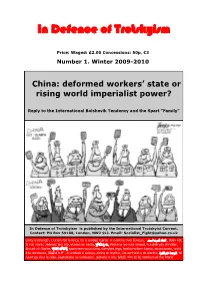

In Defence of Trotskyism No.1

In Defence of Trotskyism Price: Waged: £2.00 Concessions: 50p, €3 Number 1. Winter 2009-2010 China: deformed workers‟ state or rising world imperialist power? Reply to the International Bolshevik Tendency and the Spart “Family” In Defence of Trotskyism is published by the International Trotskyist Current. Contact: PO Box 59188, London, NW2 9LJ. Email: [email protected] đoàn kết , اتحاد قدرت است . ,Unity is strength, L'union fait la force, Es la unidad fuerza, Η ενότητα είναι δύναμη là sức mạnh, Jedność jest siła, ykseys on kesto, યુનિટિ થ્રૂ .િા , Midnimo iyo waa awood, hundeb ydy chryfder, unità ,אחדות היא כוח ,Einheit ist Stärke, एकता शक्ति, है единстве наша сила, vienybės jėga, bashkimi ben fuqine Ní ,الوحدة هو القوة ,è la resistenza, 団結は力だ", A unidade é a força, eining er styrkur, De eenheid is de sterkte neart go chur le céile, pagkakaisa ay kalakasan, jednota is síla, 일성은 이다 힘 힘, Workers of the World In Defence of Trotskyism page 2 Introducing In Defence of Trotskyism To the International Trotskyist Current he International Trotskyist Current has begun this series of theoretical and Date: Wednesday, 7 January, 2009, 10:34 PM polemical journals because much of the material is very specialised and We read your 20-point Platform with interest, and note directed at the Trotskyist ―Family‖ and far left currents who take theory your agreement with Trotsky that programme must seriously and are familiar with the historical conflicts and lines of demarca- T come first. While some points of your platform are for- tion which constitutes the history of revolutionary Trotskyism. -

Master Thesis

MASTER THESIS Titel der Master Thesis / Title of the Master’s Thesis „Opportunities and Limits for a Non-Sovereign Nation on the International Stage: The Case of the Faroe Islands“ verfasst von / submitted by Rósa Heinesen angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Advanced International Studies (M.A.I.S.) Wien 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt A 992 940 Postgraduate programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Universitätslehrgang lt. Studienblatt Internationale Studien / International Studies Postgraduate programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Professor Arthur R. Rachwald 1 Abstract: Through an historical and International Relations point of view, the thesis investigates the options available for the non-sovereign Faroe Islands to expand their political presence and participation in the international arena, without secession from the Kingdom of Denmark. With reference to paradiplomacy theory, the study is guided by the multi response questionnaire technique, providing an outline of historical tendencies combined with current dispositions of Faroese and Danish authorities. The study finds that Danish arguments against the possibility of further Faroese autonomy in foreign affairs are inconsistent from an historical perspective, and that current external factors, such as the growing global focus on the Arctic, are prompting Danish politicians to consider options previously deemed impossible. Together, these findings represent a momentum, which the Faroe Islands may take advantage of to demand change. Key words: Faroe Islands, Paradiplomacy, Kingdom of Denmark, International Relations, Foreign Policy Zusammenfassung: Unter Berücksichtigung historischer und internationaler Beziehungen untersucht die vorliegende Arbeit die vorhandenen Möglichkeiten der nicht-souveränen Färöer Inseln ihre politische Bedeutung auf der internationalen Ebene auszubauen, ohne dadurch die Abspaltung vom Dänischen Königreichs voranzutreiben. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of George Breitman

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet George Breitman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Sidelines, notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: George Breitman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Alberts ; G.B. ; Philip Blake ; Drake ; Chester Hofla ; Anthony Massini ; Albert Parker ; John F. Petrone ; Sloan ; G. Sloane Date and place of birth: February 28, 1916, Newark, NJ (USA) Date and place of death: April 19, 1986, New York, NY (USA) Nationality: USA Occupations, careers, etc.: Writer, editor, printer, historian, party organizer, political leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1935 - 1986 (lifelong Trotskyist) Biographical sketch Note: This biographical sketch is primarily based on A tribute to George Breitman : writer, organizer, revolutionary / ed. by Naomi Allen and Sarah Lovell, New York, NY, 1987 (containing obituaries, reminiscences and appraisals of G. Breitman by some 50 individuals and some 14 organizations) and on other items listed below under the heading Selective bibliography: books and articles about Breitman. George Breitman was born on February 28, 1916 at Newark, New Jersey, as son of Benjamin Breit man, an iceman, and his wife Pauline (b. Trattler), a houseworker. George Breitman grew up in a Ne wark working class neighbourhood together with his brother Samuel and his elder sister Celia, who soon joined the ranks of the Young Communist League (YCL), the Communist Party’s youth organiza tion, and who had a strong influence on George. He began to read voraciously, one of his favourite hangouts being the Newark Public Library. In 1932, in midst the Great Depression, he graduated from Newark Central High School and like most of his classmates had to join the ranks of the unemployed youth. -

Oral History Transcript T-0217, Interview with David Burbank

ORAL HISTORY T-0217 INTERVIEW WITH DAVID BURBANK INTERVIEWED BY NOEL DARK SOCIALIST PARTY PROJECT NOVEMBER 29, 1972 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. My name is Noel Clark. I am a graduate student at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. The date is November 29, 1972. I am going to talk this evening to Mr. David Burbank about the Socialist Party in the State of Missouri. CLARK: Mr. Burbank, would you mind, first of all, saying your name? BURBANK: Yes, I am David Burbank. CLARK: ...and your address. BURBANK: My address is 300 Mansion Center, St. Louis. CLARK: Okay. Mr. Burbank, would you mind giving us a short history on the Socialist Party as you first became acquainted with it? BURBANK: Well, I think I might start out by giving a little bit of background. As you probably know, the Socialist Party was greatly reduced after World War I. The Red scares and the Communist split reduced it nationally to very little. There were several cities where they had originally been very strong before World War I and even during World War I. St. Louis was one of them. There was a very large German population and this party here was, to a very large extent, a German organization. It had been so for a long time. The German Socialists were active in various German Unions, like the brewery works, the carpenters, machinists and so on, and exercised considerable influence in these unions. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England.