Programme 3 the Tudor Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vanguard Way

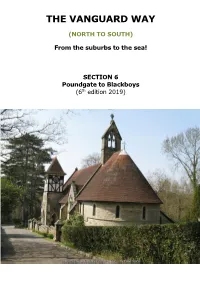

THE VANGUARD WAY (NORTH TO SOUTH) From the suburbs to the sea! SECTION 6 Poundgate to Blackboys (6th edition 2019) THE VANGUARD WAY ROUTE DESCRIPTION and points of interest along the route SECTION 6 Poundgate to Blackboys COLIN SAUNDERS In memory of Graham Butler 1949-2018 Sixth Edition (North-South) This 6th edition of the north-south route description was first published in 2019 and replaces previous printed editions published in 1980, 1986 and 1997, also the online 4th and 5th editions published in 2009 and 2014. It is now only available as an online resource. Designed by Brian Bellwood Published by the Vanguards Rambling Club 35 Gerrards Close, Oakwood, London, N14 4RH, England © VANGUARDS RAMBLING CLUB 1980, 1986, 1997, 2009, 2014, 2019 Colin Saunders asserts his right to be identified as the author of this work. Whilst the information contained in this guide was believed to be correct at the time of writing, the author and publishers accept no responsibility for the consequences of any inaccuracies. However, we shall be pleased to receive your comments and information of alterations for consideration. Please email [email protected] or write to Colin Saunders, 35 Gerrards Close, Oakwood, London, N14 4RH, England. Cover photo: Holy Trinity Church in High Hurstwood, East Sussex. cc-by-sa/2.0. © Dave Spicer Vanguard Way Route Description: Section 6 SECTION 6: POUNDGATE TO BLACKBOYS 11.1 km (6.9 miles) This version of the north-south Route Description is based on a completely new survey undertaken by club members in 2018. This section is an idyllic area of rolling countryside and small farms, mostly in open countryside and pastures. -

Sevenoaks District Accommodation Availability List

Sevenoaks District Accommodation Availability List Eastern Sevenoaks: Chipstead, Crouch, Dunk’s Green, Ightham, Kemsing, Seal, Shipbourne, Stone Street, Wrotham Heath Western Sevenoaks: Brasted, Cowden, Edenbridge, Marsh Green Locations: Northern Sevenoaks: Dunton Green, Knockholt, Shoreham Southern Sevenoaks: Hildenborough, Tonbridge, Weald Central Sevenoaks: Sevenoaks town EASTERN SEVENOAKS : Chipstead, Crouch, Dunk’s Green, Ightham, Kemsing, Seal, Shipbourne, Stone Street, Wrotham Heath Current Availability 13 – 27 November 2017 Chipstead/ Crossways House Ensuite room or private Chevening Cross Rd Chevening £: 50 – 90; apartment £85 per night Please phone for latest bathroom near Chevening/Chipstead TN14 6HF availability 2 bed/2 bath self-catering Mrs Lela Weavers apartment for 6 Near Darent Valley Path & North T: 01732 456334 Downs Way. E: [email protected] Borough Green, Yew Tree Barn WiFi access Long Mill Lane (Crouch) £: 60 – 130 13 – 27 November Ensuite rooms Crouch Family rooms Borough Green TN15 8QB Tricia & James Barton Guest sitting rooms T: 01732 780461 or 07811 505798 Partial disabled room(s) Converted barn built around 1810 E: [email protected] located in a tranquil, secluded hamlet www.yewtreebarn.com with splendid views across open countryside. Excellent base for touring Kent, Sussex & London. Ightham The Studio at Double Dance Broadband Tonbridge Road £: 70 – 80 15 - 23 November WiFi access Ightham TN15 9AT Ensuite room A stylish self-contained annexe Penny Cracknell Kent Breakfast overlooking -

'All Wemen in Thar Degree Shuld to Thar Men Subiectit Be': the Controversial Court Career of Elisabeth Parr, Marchioness Of

‘All wemen in thar degree shuld to thar men subiectit be’: The controversial court career of Elisabeth Parr, marchioness of Northampton, c. 1547-1565 Helen Joanne Graham-Matheson, BA, MA. Thesis submitted to UCL for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Declaration I, Helen Joanne Graham-Matheson confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis reconstructs and analyses the life and agency of Elisabeth Parr, marchioness of Northampton (1526-1565), with the aim of increasing understanding of women’s networks of influence and political engagement at the mid-Tudor courts, c. 1547- 1565. Analysis of Elisabeth’s life highlights that in the absence of a Queen consort the noblewomen of the Edwardian court maintained and utilized access to those in power and those with political significance and authority. During the reign of Mary Tudor, Elisabeth worked with her natal family to undermine Mary’s Queenship and support Elizabeth Tudor, particularly by providing her with foreign intelligence. At the Elizabethan court Elisabeth regained her title (lost under Mary I) and occupied a position as one of the Queen’s most trusted confidantes and influential associates. Her agency merited attention from ambassadors and noblemen as well as from the Emperor Maximilian and King Erik of Sweden, due to the significant role she played in several major contemporary events, such as Elizabeth’s early marriage negotiations. This research is interdisciplinary, incorporating early modern social, political and cultural historiographies, gender studies, social anthropology, sociology and the study of early modern literature. -

Set in the Beautiful Kent Countryside

SET IN THE BEAUTIFUL KENT COUNTRYSIDE LESS THAN AN HOUR FROM LONDON 2018 hevercastle.co.uk CASTLE Experience 700 years of history at the romantic Castle once the childhood home of Anne Boleyn. The splendid rooms hold an important collection of Tudor paintings, fine furniture, tapestries, antiques and two prayer books inscribed and signed by Anne Boleyn herself. Today, much of what you see is the result of the remarkable efforts of William Waldorf Astor. A section of the Castle is dedicated to the Astor family and the Edwardian period. CASTLE MULTIMEDIA GUIDES Available in English, French, German, Adult £3.75 Dutch, Russian and Chinese Child £3.75 Available in English only KING HENRY VIII’S DRAWING INNER BEDCHAMBER ROOM HALL GARDENS Discover magnificent award-winning gardens set in 125 acres of glorious grounds. No matter what time of year you visit, you are guaranteed an impressive display. Marvel at the Pompeiian Wall and classical statuary in the Italian Garden, admire the giant topiary chess set in the Tudor Garden and inhale the fragrance of over 4,000 rose bushes in the Rose Garden. A stroll along the Long Border, Diana’s Walk, Blue Corner and Rhododendron Walk provide colour and interest throughout the year. Wander further afield and enjoy Sunday Walk and Church Gill Walk, which follow a stream through peaceful surroundings. R O S E TUDOR ITALIAN GARDEN GARDEN GARDEN ATTRACTIONS YEW WATER TUDOR MAZE MAZE TOWERS YEW MAZE Enjoy the challenge of finding your way through the 100 year old Yew Maze.* WATER MAZE Experience the Water Maze -

January 2021 Minutes

Chelsham & Farleigh Parish Council The minutes of the virtual meeting over Zoom of the Parish Council of Chelsham & Farleigh held on Monday 4th January 2021 at 7:30pm Attendees: Cllr Jan Moore - Chairman Cllr Peter Cairns Cllr Lesley Brown Cllr Barbara Lincoln Cllr Neil Chambers Cllr Jeremy Pursehouse ( Parish & District Councillor) Cllr Celia Caulcott (District Councillor) Cllr Becky Rush (County Councillor) Mrs Maureen Gibbins - Parish Clerk & RFO ————————————————————————————————— M I N U T E S 1. Apologies for absence Cllr Nancy Marsh and District Cllr Simon Morrow 2. Declaration of Disclosable Pecuniary Interest by Councillors of personal pecuniary interests in matters on the agenda, the nature of any interests, and whether the member regards the interest to be prejudicial under the terms of the new Code of Conduct. Anyone with prejudicial interest must, unless an exception applies, or a dispensation has been issued, withdraw from the meeting. There was no specific declaration of interest although all the Councillors have an interest in the area due to living in the Parish 3. A period of fifteen minutes (including County and District Councillors reports) are available for the public to express a view or ask a question on relevant matters on the following agenda. 10 members of the public were in attendance of which 8 were observing the meeting and 1 spoke regarding the high speed fibre broadband and another the issues regarding the bridleway at Holt Wood. County Cllr Becky Rush - had a site meeting with residents prior to Christmas in relation to the highways issues regarding the crematorium. Cllr Rush is meeting with Highways Officers on 8th January raise the concerns and issues highlighted by resi- dents at the pre Christmas meeting. -

New-Lipchis-Way-Route-Guide.Pdf

Liphook River Rother Midhurst South New Downs South Lipchis Way Downs LIPHOOK Midhurst RAMBLERS Town Council River Lavant Singleton Chichester Footprints of Sussex Pear Tree Cottage, Jarvis Lane, Steyning, West Sussex BN44 3GL East Head Logo design – West Sussex County Council West Wittering Printed by – Wests Printing Works Ltd., Steyning, West Sussex Designed by – [email protected] 0 5 10 km © 2012 Footprints of Sussex 0 5 miles Welcome to the New New Lipchis Way This delightful walking trail follows existing rights of way over its 39 mile/62.4 kilometre route from Liphook, on Lipchis Way the Hampshire/West Sussex border, to East Head at the entrance to Chichester Harbour through the heart of the South Downs National Park.. Being aligned north-south, it crosses all the main geologies of West Sussex from the greensand ridges, through Wealden river valleys and heathlands, to the high chalk downland and the coastal plain. In so doing it offers a great variety of scenery, flora and fauna. The trail logo reflects this by depicting the South Downs, the River Rother and Chichester Harbour. It can be walked energetically in three days, bearing in mind that the total ‘climb’ is around 650 metres/2,000 feet. The maps divide it into six sections, which although unequal in distance, break the route into stages that allow the possible use of public transport. There is a good choice of accommodation and restaurants in Liphook, Midhurst and Chichester, elsewhere there is a smattering of pubs and B&Bs – although the northern section is a little sparse in that respect. -

Issues in Review

Issues in Review Elizabeth Schafer (Contributing Editor), Alison Findlay, Ramona Wray, Yasmin Arshad, Helen Hackett, Emma Whipday, Rebecca McCutcheon Early Modern Women Theatre Makers Introduction: Attending to Early Modern Women as Theatre Makers Elizabeth Schafer Early Theatre 17.2 (2014), 125–132 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.18.2.2600 This essay introduces the playwrights under consideration and looks forward to the four essays in this section examining the work of early modern women theatre makers. The introduction ends with a census of early modern women’s plays in modern performance. This Issues in Review focuses on the performance of early modern plays created by women theatre makers, that is, women who wrote, translated, published, commissioned and, in all probability, produced and performed in plays. But these plays have been corseted and closeted by critics — some of them feminist — who have claimed access to the theatre makers’ inten- tions and have asserted, despite no documentary evidence, that these plays were not intended to be performed. In particular these plays have been half strangled by critics’ use of the anachronistic and inappropriate nineteenth- century term ‘closet drama’. The methodology used here to uncloset and uncorset three of these plays — Lady Jane Lumley’s Iphigenia in Aulis, Eliza- beth Cary’s The Tragedy of Mariam, and the Mary Sidney Herbert commis- sioned Cleopatra by Samuel Daniel — is to explore them by means of the Elizabeth Schafer ([email protected]) is professor of drama and theatre studies at Royal Holloway, University of London. 125 126 Issues in Review collective, creative, and community-based acts of criticism that take place when the plays are performed today. -

Spring-2005.Pdf

ssssssissss SPRING2OO5 Century";"Horshom Folklore"; "The Developmentof FIR5T ?T YEAR5OF THE the Wealdenfronworks in Tudor Times";"D-Day in West Sussex";"Crisis in Forming"ond "The Sussex RUDoWTCKPRE5ERVATION Wildfife Trust". There hove beenof leost two "Any Questions?" sessionsas well os tolks by Society socrEw members like Molcolm Froncis ond Joe ond Chris John Cozens Griffin. Almost without exceptionthe speokershove concern of the This y€rlr the Society, in the traditionol senseof being been outstondingly good ond o major high stondord 2L yeors old, comes of age. fts seed wos sownat on presenf Committee is to mointainthot of speaker or subject emergencypublic meeting held in the villoge in the without being too repetitive eorly 80's to voice concern obout o ProPosedhigh motter. density housingdevelopment in The Hoven.At thot Society commentson all meeting the orguments put forword by Horshom ft is well-knownthat the the villoge,as we District Councilplanning officers were destroyed by pfanningopplications affecting where it is merited concernedvillogers, porticularly Ston Smith, and the believethot proise is os importont thot we proposolwos subseguentlyobondoned- A concernfor as is blome where it is deserved.ft follows like Foxholesond the proper control of locolbuilding development hos hoveconsidered major developments thot beenot the f orefront of the Society's qctivities ever Churchmqn'sMeodow os well os the little closes applications since. have been developedrecenlly and the the relevant to individuolhouses only. From on opplicotion -

Ashurst Circular Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Ashurst Circular walk A walk via Pooh Bridge to the attractive Wealden village of Hartfield, with a longer option over the elevated heathland of Ashdown Forest. Length Main Walk: 19½ km (12.1 miles). Four hours 45 minutes walking time. For the whole excursion including trains, sights and meals, allow at least 9½ hours. Long Circular Walk: 24¼ km (15.0 miles). Six hours walking time. Short Circular Walk: 15 km (9.3 miles). Three hours 30 minutes walking time. OS Map Explorer 135. Ashurst, map reference TQ507388, is on the East Sussex/Kent border, between East Grinstead and Tunbridge Wells. Toughness 5 out of 10 (7 for the Long Walk, 3 for the Short Walk). Features This walk makes a gentle start along the Medway valley, soon joining the Wealdway long-distance path. After an early pub lunch in the small village of Withyham with its notable parish church there is a choice of three routes. All lead eventually to the neighbouring village of Hartfield, associated with the author AA Milne and his most famous creation: coachloads of tourists regularly descend on Pooh Corner to buy all manner of Winnie-the-Pooh memorabilia. The Short Walk heads directly for this village, while the other variations continue through the extensive Buckhurst Estate into Five Hundred Acre Wood. This is the furthest point for the Main Walk, which crosses the famous Pooh Bridge on its way round to Hartfield. The Long Walk climbs steadily through the wood and continues around the rim of a valley in Ashdown Forest, the largest area of elevated heathland in south-east England. -

Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn's Femininity Brought Her Power and Death

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Senior Honors Projects Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2018 Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death Rebecca Ries-Roncalli John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ries-Roncalli, Rebecca, "Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death" (2018). Senior Honors Projects. 111. https://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers/111 This Honors Paper/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death Rebecca Ries-Roncalli Senior Honors Project May 2, 2018 Ries-Roncalli 1 I. Adding Dimension to an Elusive Character The figure of Anne Boleyn is one that looms large in history, controversial in her time and today. The second wife of King Henry VIII, she is most well-known for precipitating his break with the Catholic Church in order to marry her. Despite the tremendous efforts King Henry went to in order to marry Anne, a mere three years into their marriage, he sentenced her to death and immediately married another woman. Popular representations of her continue to exist, though most Anne Boleyns in modern depictions are figments of a cultural imagination.1 What is most telling about the way Anne is seen is not that there are so many opinions, but that throughout over 400 years of study, she remains an elusive character to pin down. -

Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: from Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-09-24 Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) Gray, Moorea Gray, M. (2015). Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27395 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2486 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) by Mooréa Gray A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SePtember, 2015 © Mooréa Gray 2015 Abstract The Penshurst grouP of Poems (1616-1799) is a collection of twelve Poems— beginning with Ben Jonson’s country-house Poem “To Penshurst”—which praises the ancient estate of Penshurst and the eminent Sidney family. Although praise is a constant theme, only the first five Poems Praise the resPective Patron and lord of Penshurst, while the remaining Poems Praise the exemplary Sidneys of bygone days, including Sir Philip and Dorothy (Sacharissa) Sidney. This shift in praise coincides with and is largely due to the gradual shift in literary economy: from the Patronage system to the literary marketPlace. -

Brockholt Cottages, Kent

DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT AND PLANNING STATEMENT Planning Application Document Brockholt Cottage architects Butterwell Hill, Cowden, Kent TN8 7HB LONDON | KENT © December 2015 Version 1.1 existing view 1 existing view 2 existing view 3 existing view 4 Issue Revision By Ck'd Date FOLLOW FIGURED DIMENSIONS ONLY Drawing: Job No: Drawing No: Rev: DO NOT SCALE C CHECK ALL LEVELS AND DIMENSIONS ON SITE MILLER ARCHITECTS REPORT ALL DISCREPANCIES TO THE ARCHITECT MEDWAY HOUSE STUDIO Existing Views 0848 103 THIS DRAWING IS SUITABLE FOR TOWN PLANNING PURPOSES ONLY HIGH STREET NOT TO BE USED FOR CONSTRUCTION Project: COWDEN Date: Sept 2015 Scale: NTS © COPYRIGHT - NO COPY OR REPRODUCTION IS EDENBRIDGE, KENT TN8 7JQ PERMITTED WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT OF MILLER Brockholt Cottage, Cowden, Kent Drawn: Checked: ARCHITECTS Tel: 020 7193 1473 www.miller-architects.co.uk DRT SM architects LONDON | KENT existing view 1 existing view 2 Prepared by, DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT AND Miller Architects and Associates Ltd existing view 3 existing view 4 Medway House Studio PLANNING STATEMENT High Street Cowden Planning Application Document Kent TN8 7JQ Brockholt Cottage Butterwell Hill, Cowden, Kent TN8 7HB Architect Issue Revision By Ck'd Date FOLLOW FIGURED DIMENSIONS ONLY Drawing: Job No: Drawing No: Rev: DO NOT SCALE C Susanna Miller © December 2015 CHECK ALL LEVELS AND DIMENSIONS ON SITE MILLER ARCHITECTS REPORT ALL DISCREPANCIES TO THE ARCHITECT MEDWAY HOUSE STUDIO Existing Views 0848 103 BA Arch (Hons), Dip Arch, Dip Historic Building Conservation (AA), RIBA Version 1.1 THIS DRAWING IS SUITABLE FOR TOWN PLANNING PURPOSES ONLY HIGH STREET NOT TO BE USED FOR CONSTRUCTION Project: COWDEN Date: Sept 2015 Scale: NTS © COPYRIGHT - NO COPY OR REPRODUCTION IS EDENBRIDGE, KENT TN8 7JQ PERMITTED WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT OF MILLER Brockholt Cottage, Cowden, Kent Drawn: Checked: ARCHITECTS Tel: 020 7193 1473 www.miller-architects.co.uk DRT SM Butterwell Hill - Google Maps https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Butterwell+Hill,+Cowden,..