For Srebrenica's Most Wanted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safet Zajko” Započeli Radovi Na Uređenju

Broj: 9 juli-avgust 2014. godine Informativni časopis Općine Novi Grad Sarajevo Interviju sa Mirsadom Purivatrom Općina dobila na korištenje kasarnu “Safet Zajko” Započeli radovi na uređenju Počela rekonstrukcija POSAO ZA 15 PRIPRAVNIKA POSJETA DELEGACIJE KROVOVA I FASADA ISTANBULSKE oPĆine beYOGLU stambenih zgrada VAŽNIJI TELEFONI I E-MAIL ADRESE SADRŽAJ: Služba za poslove Općinskog vijeća 033 291-130, fax. 033 291-271 [email protected] Intervju 4 Općinsko pravobranilaštvo 033 291-162 [email protected] Općinsko vijeće 7 Stručna služba za poslove kabineta općinskog načelnika i zajedničke poslove 033 291-100 033 291-103; fax. 033 291-278 Kabinet načelnika 12 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Privreda 21 Općinska služba za obrazovanje, kulturu, sport i lokalni integrisani razvoj 033 291 117 Infrastruktura 27 033 291 281; fax. 291 170 [email protected] Općinska služba za boračka pitanja, rad, Sarajevo kroz historiju 44 socijalna pitanja i zdravstvo 291-237; fax.291-164 [email protected] Obrazovanje 50 033 291-173; fax. 291-173 [email protected] 291-306; fax.291-281 Kultura 56 Općinska služba za privredu, finansije i inspekcijske poslove 033 291-122 [email protected] Sport 58 [email protected] [email protected] 291-234; fax.291-319 Obilježavanja 62 [email protected] Općinska služba za urbanizam, imovin- sko-pravne poslove i katastar nekretnina Ostale vijesti 80 033 291-120; fax. -

Srebrenica - Intro ENG.Qxp 21/07/2009 2:59 PM Page 1

srebrenica - intro ENG.qxp 21/07/2009 2:59 PM Page 1 BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN THE ICTY AND COMMUNITIES IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA CONFERENCE SERIES SREBRENICA 21 MAY 2005 srebrenica - intro ENG.qxp 21/07/2009 2:59 PM Page 2 BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN THE ICTY AND COMMUNITIES IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA The Bridging the Gap conference in Srebrenica would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of many people and agencies. Our thanks to all those that made this remarkable series possible. Appreciation is expressed to the Helsinki Committee in Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Their commitment to truth-seeking and upholding basic human values, often in the face of hostility, is acknowledged. The event was generously supported by the Neighbourhood Programme of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Heartfelt appreciation is extended to those people most affected by the crimes addressed at the conference. Without their bravery, nothing could be accomplished. ii Bridging the Gap between the ICTY and communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina CONFERENCE SERIES SREBRENICA 21 MAY 2005 A publication of the Communications Service, Registry, ICTY Contents Editor: Liam McDowall Graphics Editor: Leslie Hondebrink-Hermer Contributors: Ernesa Begi}-Ademagi}, Rebecca Cuthill, Matias Hellman, James Landale, Natalie O’Brien Printed by Albani drukkers, The Hague, Netherlands 2009 SREBRENICA srebrenica - intro ENG.qxp 21/07/2009 2:59 PM Page 3 BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN THE ICTY AND COMMUNITIES IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Table of contents Map -

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

Dragana Mašović

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol. 2, No 8, 2001, pp. 545 - 555 THE ROMANIES IN SERBIAN (DAILY) PRESS UDC 316.334.52:070(=914.99) Dragana Mašović Faculty of Philosophy, Niš Abstract. The paper deals with the presence of Romanies' concerns in Serbian daily press. More precisely, it tries to confirm the assumption that not enough space is devoted to the issue as evident in a small-scale analysis done on seven daily papers during the sample period of a week. The results show that not only mere absence of Romanies' issues is the key problem. Even more important are the ways in which the editorial startegy and the language used in the published articles turn out to be (when unbiased and non-trivial) indirect, allusive and "imbued with promises and optimism" so far as the presumed difficulties and problems of the Romanies are concerned. Thus they seem to avoid facing the reality as it is. Key Words: Romanies, Serbian daily press INTRODUCTION In Mary Woolstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1972) there is an urgent imperative mentioned that can also be applied to the issue of Romanies presence in our press. Namely, she suggested that "in the present state of society it appears necessary to go back to first principles in search of the most simple truths, and to dispute with some prevailing prejudice every inch of ground." More precisely, in the case of the Romanies' presence in the press the question to be asked is what would be the "first principles" that Woolstonecraft refers to? No doubt that in this context they refer to what has always been considered the very basis of every democratic, open-minded and tolerant society, that is, the true equality of all the citizens as reflected in every aspect of the society that proclaims itself to be multi-cultural. -

Bill Clinton, the Bosnian War, and American Foreign Relations in the Post-Cold War Era, 1992-1995

VISIONARY POLICY: BILL CLINTON, THE BOSNIAN WAR, AND AMERICAN FOREIGN RELATIONS IN THE POST-COLD WAR ERA, 1992-1995 James E. CovinGton III A thesis submitted to the faculty at the UniveRsity of NoRth CaRolina at Chapel Hill in paRtial fulfillment of the RequiRements foR the deGRee of MasteR of Arts in the Military History program in the DepaRtment of HistoRy. Chapel Hill 2015 AppRoved by: Michael C. MoRgan Wayne E. Lee Joseph W. Caddell © 2015 James E. CovinGton III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT James E. CovinGton III: VisionaRy Policy: Bill Clinton, the Bosnian WaR, and AmeRican Foreign Policy in the Post-Cold War Era, 1992-1995 (Under the direction of Michael C. MoRGan) Bill Clinton assumed office duRinG a particularly challenging peRiod of AmeRican histoRy. AfteR the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States enjoyed a period of unprecedented power and authority. Clinton was elected to office laRGely for his domestic policies, howeveR, his vision foR AmeRica’s position in the post-Cold War woRld steeRed his foReign policy, particularly with respect to Europe. Clinton’s vision was moRe inclusive and encompassinG than that of his predecessor, George H. W. Bush. During the post-Cold WaR yeaRs, Bush was moRe inclined to let EuRope soRt out theiR own pRoblems, particularly in the case of Bosnia. Clinton, however, was moRe willing to see post-Cold WaR EuRopean pRoblems as AmeRican issues. The Bosnian WaR RepResents a point wheRe these two ideals collided. Guided by this vision, Clinton oveRcame challenGes fRom the EuRopean Community, political adveRsaRies, and even his own public en Route to inteRveninG in Bosnia. -

Media Watch Serbia1 Print Media Monitoring

Media Watch Serbia1 Print Media Monitoring METHODOLOGY The analysis of the daily press from the viewpoint of the observance of generally accepted ethical norms is based on a structural quality analysis of the contents of selected newspaper articles. The monitoring includes eight dailies: Politika, Danas, Vecernje novosti, Blic, Glas javnosti, Kurir, Balkan and Internacional. Four weeklies are also the subject of the analysis: Vreme, NIN, Evropa and Nedeljni Telegraf. The basic research question requiring a reply is the following: What are the most frequent forms of the violation of the generally accepted ethical norms and standards in the Serbian press? The previously determined and defined categories of professional reporting are used as the unit of the analysis in the analysis of ethical structure of reporting. The texts do not identify all the categories but the dominant ones only, three being the maximum. The results of the analysis do not refer to the space they take or the frequency of their appearances but stress the ethical norms mostly violated and those which represent the most obvious abuse of public writing by the journalists. The study will not only point out typical or representative cases of non-ethical reporting but positive examples as well whereas individual non- standard cases of the violation of the professional ethics will be underlined in particular. Finally, at the end of each monitoring period, a detailed quality study of selected articles will provide a deep analysis of the monitored topics and cases. 1 The Media Watch Serbia Cultural Education and Development Project for Increasing Ethical and Legal Standards in Serbian Journalism is financed and supported by UNESCO. -

FOM Director

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe The Representative on Freedom of the Media Freimut Duve Report to the Permanent Council Vienna, 30 March 2000 Madame Chairperson, Ladies and Gentlemen, In my first quarterly report to the Permanent Council this year, I will cover our main activities since December 1999. And as last year, at the end of March, I would like to present to you again our Yearbook that covers our main themes and activities since February 1999. But first of all, two remarks on current issues: I am concerned about developments in Kyrgyzstan last week. One journalist of Res Publika newspaper was arrested for some days after covering a peaceful demonstration in Bishkek. Vash Advocat has seized publication as the tax inspection authorities have frozen its accounts. The state-owned distribution network has refused to distribute three newspapers. These developments are disturbing in the election context as all papers in question were involved in election coverage. On Belarus: More than 30 journalists, both Belarusian and international were arrested during the opposition-staged demonstration in Minsk on 25 March. The police did not express the reason for detention. Some of the journalists have been illegally searched, some lost their film and other equipment, and none were permitted to inform relatives or employers about their detention. This type of action is totally unacceptable in an OSCE participating State and must be condemned in the strongest terms. It endangers, once more, the political and social dialogue in Belarus about elections in the course of this year. I have asked the Foreign Minister to ensure that the journalists remaining in custody should be immediately released. -

International Press

International press The following international newspapers have published many articles – which have been set in wide spaces in their cultural sections – about the various editions of Europe Theatre Prize: LE MONDE FRANCE FINANCIAL TIMES GREAT BRITAIN THE TIMES GREAT BRITAIN LE FIGARO FRANCE THE GUARDIAN GREAT BRITAIN EL PAIS SPAIN FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG GERMANY LE SOIR BELGIUM DIE ZEIT GERMANY DIE WELT GERMANY SUDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG GERMANY EL MUNDO SPAIN CORRIERE DELLA SERA ITALY LA REPUBBLICA ITALY A NEMOS GREECE ARTACT MAGAZINE USA A MAGAZINE SLOVAKIA ARTEZ SPAIN A TRIBUNA BRASIL ARTS MAGAZINE GEORGIA A2 MAGAZINE CZECH REP. ARTS REVIEWS USA AAMULEHTI FINLAND ATEATRO ITALY ABNEWS.RU – AGENSTVO BUSINESS RUSSIA ASAHI SHIMBUN JAPAN NOVOSTEJ ASIAN PERFORM. ARTS REVIEW S. KOREA ABOUT THESSALONIKI GREECE ASSAIG DE TEATRE SPAIN ABOUT THEATRE GREECE ASSOCIATED PRESS USA ABSOLUTEFACTS.NL NETHERLANDS ATHINORAMA GREECE ACTION THEATRE FRANCE AUDITORIUM S. KOREA ACTUALIDAD LITERARIA SPAIN AUJOURD’HUI POEME FRANCE ADE TEATRO SPAIN AURA PONT CZECH REP. ADESMEUFTOS GREECE AVANTI ITALY ADEVARUL ROMANIA AVATON GREECE ADN KRONOS ITALY AVLAIA GREECE AFFARI ITALY AVLEA GREECE AFISHA RUSSIA AVRIANI GREECE AGENZIA ANSA ITALY AVVENIMENTI ITALY AGENZIA EFE SPAIN AVVENIRE ITALY AGENZIA NUOVA CINA CHINA AZIONE SWITZERLAND AGF ITALY BABILONIA ITALY AGGELIOF OROS GREECE BALLET-TANZ GERMANY AGGELIOFOROSTIS KIRIAKIS GREECE BALLETTO OGGI ITALY AGON FRANCE BALSAS LITHUANIA AGORAVOX FRANCE BALSAS.LT LITHUANIA ALGERIE ALGERIA BECHUK MACEDONIA ALMANACH SCENY POLAND -

Investigative Mission By

FACT-FINDING MISSION BY THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AD HOC DELEGATION TO VOÏVODINA AND BELGRADE (29-31 JANUARY 2005) REPORT Brussels, 2 March 2005 DV\559830EN.doc PE 350.475 EN EN CONTENTS Page I.INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 3 II.THE EVENTS......................................................................................................... 5 III.CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................... 11 ANNEXES ................................................................................................................. 13 PE 350.475 2/20 DV\559830EN.doc EN I. INTRODUCTION Voïvodina, a region in Northern Serbia, is the southern part of the Pannonian plane, bordering with Croatia on the west, Romania on the east and Hungary to the north. The surface area is 21,506 km2, almost as large as Slovenia, with two million inhabitants of some twenty different nationalities. At the end of the IXth century, the Hungarians colonised Voïvodina, which became part of the Kingdom of Hungary and stayed so until the Turkish occupation in 1529. When the latter ended at the turn of the XVII-XVIIIth centuries, Voïvodina was part of the Kingdom of Hungary until 1918. The region's inter-ethnic complexity is rooted in the XVIIIth century Habsburg policy of repopulation, which brought in people from the various nationalities that made up their empire at the time: Serbians fleeing Ottoman rule, Croatians, Hungarians, Germans, Slovaks, Ruthenes, etc. The events of 1848-49 had repercussions in Voïvodina, which was transformed into a region enjoying a modicum of autonomy, with the Emperor François-Joseph bearing the title Voïvode. It was then joined to Hungary in 1860, and then the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1867. Within the Compromise of 1867, Austria and Hungary undertook to treat all the various nationalities on an equal basis, and recognised the equality of all the empire's languages in schools, the administration and public life. -

Skupština Opštine Srebrenica Odluke, Zaključci, Programi I Javni Konkursi

BILTEN SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE SREBRENICA BROJ: 1/2015 Srebrenica, Januar 2015. god. SKUPŠTINA OPŠTINE SREBRENICA ODLUKE, ZAKLJUČCI, PROGRAMI I JAVNI KONKURSI Broj:01-022-185 /14 ODLUKE SKUPŠTINE OPŠTINE SREBRENICA Srebrenica, 26.12.2014. god. Broj:01-022-184/14 Na osnovu člana 31. Zakona o budžetskom sistemu Republike Srpske Srebrenica, 26.12.2014. god. ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 121/12 ), a u skladu sa Zakonom o trezoru ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 16/05 i Na osnovu člana 5. Zakona o Budžetskom sistemu Republike Srpske 92/09) i člana 30. Zakona o lokalnoj samoupravi ("Službeni glasnik ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: 121/12), člana 30. Zakona Republike Srpske", broj: 101/04, 42/05, 118/05 i 98/13) i člana 32. Statuta Opštine Srebrenica ("Bilten opštine Srebrenica", broj: 10/05), o lokalnoj samoupravi ("Službeni glasnik Republike Srpske", broj: Skupština opštine Srebrenica na XVII redovnoj sjednici održanoj 101/04, 42/05,118/05 i 98/13) i člana 32. Statuta Opštine Srebrenica 26.12.2014. godine je usvojila: ("Bilten opštine Srebrenica", broj: 10/05), Skupština opštine Srebrenica na XVII redovnoj sjednici održanoj 26.12.2014. godine je Odluku usvojila: o izvršenju Budžeta opštine Srebrenica za 2015. godinu Odluku Član 1. o usvajanju Budžeta opštine Srebrenica za 2015. godinu Ovom Odlukom propisuje se način izvršenja Budžeta Opštine Član 1. Srebrenica za 2015. godinu (u daljem tekstu: budžet). Budžet opštine Srebrenica za 2015. godinu sastoji se od: Ova Odluka će se sprovoditi u saglasnosti sa Zakonom o budžetskom sistemu Republike Srpske i Zakonom o trezoru. 1. Ukupni prihodi i primici: 6.883.00000 KM, od toga: a) Redovni prihodi tekućeg perioda: 6.115.500,00 KM; Sve Odluke, zaključci i rješenja koji se odnose na budžet moraju biti u b) Tekući grantovi i donacije: 767.500,00 KM. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science German Print Media Coverage in the Bosnia and Kosovo Wars of the 1990S Marg

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science German Print Media Coverage in the Bosnia and Kosovo Wars of the 1990s Margit Viola Wunsch A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. Abstract This is a novel study of the German press’ visual and textual coverage of the wars in Bosnia (1992-95) and Kosovo (1998-99). Key moments have been selected and analysed from both wars using a broad range of publications ranging from extreme-right to extreme-left and including broadsheets, a tabloid and a news-magazine, key moments have been selected from both wars. Two sections with parallel chapters form the core of the thesis. The first deals with the war in Bosnia and the second the conflict in Kosovo. Each section contains one chapter on the initial phase of the conflict, one chapter on an important atrocity – namely the Srebrenica Massacre in Bosnia and the Račak incident in Kosovo – and lastly a chapter each on the international involvement which ended the immediate violence. -

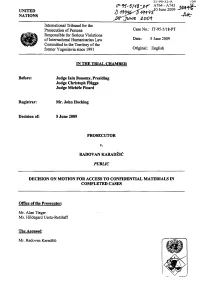

Decision on Motion for Access to Confidential Materials in Completed Cases

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Case No.: IT-95-5/1S-PT Responsible for Serious Violations ofInternational Humanitarian Law Date: 5 June 2009 Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge lain Bonomy, Presiding Judge Christoph FIUgge Judge Michele Picard Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Decision of: 5 June 2009 PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC PUBLIC DECISION ON MOTION FOR ACCESS TO CONFIDENTIAL MATERIALS IN COMPLETED CASES Office ofthe Prosecutor: Mr; Alan Tieger . Ms. Hildegard Vertz-Retzlaff The Accused: Mr. Radovan KaradZi6 • IT-98-32-A 763 THIS TRIAL CHAMBER of the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 ("Tribunal") is seised of the Accused's "Motion for Access to Confidential Materials in Completed Cases", filed on 16 April 2009 ("Motion"), and hereby renders its decision thereon, I. Background and Submissions J. On 14 April 2009, the Accused filed a "Motion to Exceed Word Limit: Access to Confidential Material in Completed Cases", not opposed by the Office of the Prosecutor ("Prosecution"),' On 15 April 2009, the Chamber issued its "Decision on Accused's Motion to Exceed Word Limit: Access to Confidential Material in Completed Cases" granting the Accused leave to exceed the word limit in the Motion by 4,000 words, 2, In paragraph one of his Motion, the Accused requests that the Trial Chamber