Your Name Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music & Videos by Holocaust

Bearing Witness BEARING WITNESS A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music, and Videos by Holocaust Victims and Survivors PHILIP ROSEN and NINA APFELBAUM Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut ● London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Philip. Bearing witness : a resource guide to literature, poetry, art, music, and videos by Holocaust victims and survivors / Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0–313–31076–9 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Bio-bibliography. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Bio-bibliography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in art—Catalogs. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Songs and music—Bibliography—Catalogs. 5. Holocaust,Jewish (1939–1945)—Video catalogs. I. Apfelbaum, Nina. II. Title. Z6374.H6 R67 2002 [D804.3] 016.94053’18—dc21 00–069153 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00–069153 ISBN: 0–313–31076–9 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii Historical Background of the Holocaust xi 1 Memoirs, Diaries, and Fiction of the Holocaust 1 2 Poetry of the Holocaust 105 3 Art of the Holocaust 121 4 Music of the Holocaust 165 5 Videos of the Holocaust Experience 183 Index 197 Preface The writers, artists, and musicians whose works are profiled in this re- source guide were selected on the basis of a number of criteria. -

Imran A.K. Surti [email protected]

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:11 November 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== REPRESENTATION OF HOLOCAUST AND PARTITION: A STUDY OF SELECT TEXTS Thesis Submitted to Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English Faculty of Arts by Imran A.K. Surti [email protected] Under the Supervision of Dr. Rakesh Desai Professor and Head, Department of English Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat October 2016 ==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:11 November 2018 Imran A.K. Surti, Ph.D. English REPRESENTATION OF HOLOCAUST AND PARTITION: A STUDY OF SELECT TEXTS Doctoral Dissertation REPRESENTATION OF HOLOCAUST AND PARTITION: A STUDY OF SELECT TEXTS Thesis Submitted to Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English (Faculty of Arts) (Registration No. 2793) By Imran A.K. Surti (Research Candidate) Under the Supervision of Dr. Rakesh Desai Professor and Head, Department Of English Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat October 2016 REPRESENTATION OF HOLOCAUST AND PARTITION: A STUDY OF SELECT TEXTS Imran A.K. Surti, Ph.D. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH VEER NARMAD SOUTH GUJARAT UNIVERSITY SURAT C E R T I F I C A T E This is to certify that this doctoral thesis entitled REPRESENTATION OF HOLOCAUST AND PARTITION: A STUDY OF SELECT TEXTS is submitted by Mr. Imran A.K. Surti for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY, in the Department of English, Faculty of Arts, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat. -

Magdalena Waligórska• Fiddler As a Fig Leaf

Magdalena Waligórska Fiddler as a Fig Leaf The Politicisation of Klezmer in Poland Klezmer music has become very popular in Poland. The Festival of Jew- ish Culture in Cracow has gained national and international significance. Nonetheless, this is about more than music. The festival has become a litmus test, by which changes in the country’s political mood and its atti- tude towards its Jewish heritage is measured. Jews in Poland are important. As a subject. A subject significant to everyone, to some – obsessive. Stanisław Krajewski, Żydzi, Judaizm, Polska1 Even a Communist government wants to be popular. Rock ’n’ roll costs nothing, so we have rock festival at the Palace of Culture. Jan in Tom Stoppard’s Rock ’n’ Roll “There is no music without ideology”, said Dmitrii Shostakovich. In Poland, which constitutes a major East European market for commercialized yidishkayt, and which is still struggling to acknowledge the Jewish perspective in its collective remembrance of the past, the recent revival of Jewish folk music reverberates not only in concert halls. While klezmer music2 accompanies anti-fascist demonstrations in Germany, and clarinetist Giora Feidman, “the king of klezmer”, is honoured with the Great Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the political significance of the klezmer revival has not been lost on Germany’s eastern neighbours either. To be sure, the politicization of this Jewish musical heritage is not a new phenome- non. In the interwar years, it was not uncommon for klezmer kapelyes (bands) to accompany political rallies or marches in Eastern Europe.3 Even in the Weimar Re- public, East European Jewish folk songs were frequently used by various Jewish ——— Magdalena Waligórska (b. -

The Phenomenological Self in the Works of Jerzy Kosinski

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 2003 The heP nomenological Self in the Works of Jerzy Kosinski Tracy Allen Houston University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Houston, Tracy Allen, "The heP nomenological Self in the Works of Jerzy Kosinski" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 33. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/33 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL SELF IN THE WORKS OF JERZY KOSINSKI BY Tracy Allen Houston B.A. University of Maine, 2001 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in English) The Graduate School The University of Maine August, 2003 Advisory Committee: Welch Everman, Professor of English, Advisor T. Jeff Evans, Associate Professor of English Steven Evans, Assistant Professor of English O 2003 Tracy Allen Houston All Rights Reserved THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL SELF IN THE WORKS OF JERZY KOSINSKI By Tracy Allen Houston Thesis Advisor: Dr. Welch Everman An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in English) August, 2003 A scholar who wishes to examine the works of Jerzy Kosinski faces a problem not found in the study of many other authors: Kosinski's personal history, critical to many approaches to the study of literature, is filled with fictions, contradictions, and unverifiable events. -

Teacher's Booklet

Teacher’s Booklet Educators are invited to consider the following words told to renowned educator and psychologist Chaim Ginott: Dear Teacher I am a survivor of a concentration camp. My eyes saw what no man should witness. Gas chambers built by learned engineers. Children poisoned by educated doctors. Infants killed by trained nurses. Women and babies shot by high school college graduates. So I am suspicious of education. My request is: Help your students to become human. Your efforts must never produce learned monsters, skilled psychopaths, educated Eichmanns. Reading, writing, arithmetic are important only if they serve to make our children more human. This booklet for teachers is designed to be used in connection with the Courage to Care program. It may not be reproduced for any purpose without the permission of Courage to Care NSW Inc. 3 Contents Introduction 4 Educational philosophy 4 Courage to Care outcomes 4 Australian curriculum outcomes 5 Program components 6 Using Courage to Care 8 Pre-visit activities 8 Activity 1: Lessons from World War II 8 Activity 2: Jewishness and antisemitism 10 Activity 3: Genocide and the Holocaust 12 Activity 4: Anecdote of an adolescent 14 Activity 5: Concealing identity 15 Activity 6: In amongst the bystanders, the Righteous 16 Activity 7: Who will speak up? 18 Post-visit activities 19 Activity 1: My apology 19 Activity 2: We are all special and unique 20 Activity 3: Create posters 22 Activity 4: Looking for tolerance around us 22 Activity 5: The painted bird 22 Activity 6: The prejudice game: we all lose 23 Glossary of terms 25 Recommended reading for students 28 Selected sources from the web 30 To teachers: this book is for use as preparatory work prior to students visiting the Courage to Care exhibition. -

The Painted Bird

THE PAINTED BIRD BOOKS BY JERZY KOSINSKI NOVELS The Painted Bird Steps Being There The Devil Tree Cockpit Blind Date Passion Play Pinball The Hermit of 69th Street ESSAYS Passing By Notes of the Author The Art of the Self NONFICTION (Under the pen name Joseph Novak) The Future Is Ours, Comrade No Third Path THE PAINTED BIRD JERZY KOSINSKI SECOND EDITION with an introduction by the author To the memory of my wife Mary Hayward Weir without whom even the past would lose its meaning Copyright © 1965, 1976 by Jerzy N. Kosinski All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected]. First published in the United States of America in 1976 by Houghton Mifflin Company Published simultaneously in Canada Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The painted bird/Jerzy Kosinski; with an introduction by the author.—2nd ed. -

BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 556843 Ii ABSTRACT Vo

JERZY KOS INSKI I A STUDY OP HIS NOVELS David J. Lipani A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1973 BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 556843 ii ABSTRACT Vo. The Introduction examined relevant aspects of Kosin ski’s life in an attempt to establish a relationship between his past experiences and the major themes of his fiction. It was discovered that the author’s exposure to diverse forms of authoritarian control constituted the source of his bias against any external force operating counter to the self’s freedom. The four novels comprising the Kosinski canon were analyzed in detail, especially as they were directed toward the quest for a viable self in a contemporary world threatening to submerge the individual consciousness. Each protagonist was shown struggling with some variant of social repression» the boy in The Painted Bird faced hostile peasants who, swayed by Nazist ideology, viewed him as a menace to their own safety» the narrator in Steps fled the socialist bloc because there he had no control of his destiny, nor was his being acknowledged as an entity separ ate from the masses» Chance, in Being There, was subjected to a more insidious totalitarianism--the television medium, whose false representation of reality effectively kneads the individual into an easily manipulated, mindless soul» and Jonathan Whalen, in The Devil Tree, fell victim to the Protestant Ethic, the demands of which left him unable to see himself as something other than an image occasioned by wealth and status. -

Anuario 2004 Grande

Anuario Nº 7 - Fac. de Cs. Humanas - UNLPam (99-107) Survival in Kosinski´s The Painted Bird Norma L. Alfonso Abstract A growing number of writers have created an entirely new form of fiction sometimes called metafiction, others surfiction or fabulation which shares a number of specific stylistic features and questions the fact that traditional works with linear plot, recognizable characters and theme as well as unity of time and space can depict a reality that is characterized by being unfixed, unknowable and chaotic. This paper is concerned with the theme of survival in the fiction of the Polish Jewish writer Jerzy Kosinski. His first well-known novel The Painted Bird (1965) is the fictionalised account of his own childhood odyssey through Eastern Europe during WW II. The story depicts the travels of a young Jewish refugee in his effort to survive, at any cost, in the time of the Holocaust. His experiences occur beyond the limits of what may be considered human actions the cruelty people are capable of inflicting upon each other in the name of war or ideology. Key words: metafiction, unfixed reality, survival, World War II, Jewish refugee. La supervivencia en la novela El Pájaro Pintado de J. Kosinski Resumen La metaficción es una ficción diferente y novedosa que posee rasgos estilísticos específicos. Esta escritura innovadora cuestiona la narrativa tradicional con un argumento lineal, con Estudios Culturales personajes y temas reconocibles, así como con unidad de tiempo y espacio porque describen una realidad que se caracteriza por ser inestable, desconocida y caótica. En este trabajo se analiza el tema de la supervivencia en la ficción del escritor polaco Jerzy Kosinski. -

The Anti-Human Condition: Violence, Identity, and Coming-Of-Age in the Painted Bird

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Undergraduate Student Research Awards Information Literacy Committee Fall 2017 The Anti-Human Condition: Violence, Identity, and Coming-of-Age in The ainP ted Bird Malcolm Conner Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/infolit_usra Repository Citation Conner, Malcolm, "The Anti-Human Condition: Violence, Identity, and Coming-of-Age in The ainP ted Bird" (2017). Undergraduate Student Research Awards. 35. https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/infolit_usra/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Information Literacy Committee at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Student Research Awards by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Anti-Human Condition: Violence, Identity, and Coming-of-Age in The Painted Bird Malcolm Conner Jerzy Kosinski’s first novel, The Painted Bird, (1965) remains one of the most controversial works of Holocaust fiction ever published. A dystopic coming-of-age story set on a Bosch-like backdrop of war-torn eastern Europe, the novel is loosely based off Kosinski’s experiences during World War II, when he and his family hid from the Nazis in rural Poland. (Sloan, 7-54) The nameless protagonist – known only as the boy – passes from village to village as an unwanted outsider, often abused and barely surviving. For six years, “the boy's life is an unmitigated series of horrors and atrocities, which though episodic in nature, disclose a sort of patterned movement through various forms of moral and physical evil [. -

THE-PAINTED-BIRD-PRESS-BREAKS.Pdf

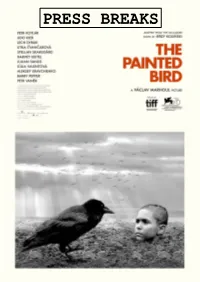

THE PAINTED BIRD - THE PAINTED BIRD - Press Breaks - FESTIVAL AND AWARDS VENICE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Cinema for UNICEF Award Winner CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Best Cinematography Award KOLKOTA FILM FESTIVAL Best Director Award WARSAW JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL Best Screenplay Award MIAMI JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL Critic’s Prize BELGARDE IFF Best Director Award CZECH LION AWARDS : 8 awards Best Film, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Film Editing, Best Sound, Best Stage Design, Best Costume Design, Best Make Up and Hairstyling, As well as : Best Film Poster, Exceptional feat in the area of audiovisual arts for Vaclav Marhoul FESTIVAL SELECTIONS (in chronological order) Toronto International Film Festival - Special Presentations La Biennale - Venice Film Festival 2019 Official Competition - Cinema for Unicef Awards BFI London Film Festival St Petersburg International Film Festival Message to Man Vancouver International Film Festival London BFI Film Festival Luxembourg CinEast Film Festival Istanbul Filmekimi Cologne Film Festival Warsaw International Film Festival Chicago International Film Festival - Best Cinematography Award for Vladimír Smutný Mostra de Sao Paulo Toruń Tofifest Tokyo International Fim Festival Thessaloniki International Film Festival Minsk International Film Festival Listapad Cork Film Festival Camerimage 2019 Kolkata International Film Festival Visegrad Cinema Days Tallinn Black Nights - THE PAINTED BIRD - Press Breaks - Cairo International Film Festival Goa International Film Festival of India Around the -

Sexy Fascism: Exemplifying the Relationship Between Sex and Power

JAKUB RAWSKI SEXY FASCISM … 133 Jakub Rawski Sexy Fascism: Exemplifying the Relationship between Sex and Power DOI: 10.18318/td.2017.en.2.9 Jakub Rawski – Associate Professor of Literature at the State Higher Vocational School in Głogów. His research interests encompass: The hungry Greeks… rummage underneath the rails. Polish emigration One of them finds some pieces of mildewed bread, another a few half-rotten sardines. They eat. Romanticism, Schweiendreck, spits a young tall guard with corn- vampirism in coloured hair and dreamy blue eyes.1 popular culture, Tadeusz Borowski literature of war and occupation, and Those, who will be beautiful, will also be wise – the broadly conceived beautiful, wise and powerful will embody the ideal of manifestations perfection. Evil, ugliness and stupidity will disappear of difference in off the face of the earth. 20th- and 21st- Will this not entail suffering and the most elabo- century literature. rate cruelty? Does the end justify the means? But of He published in course, of course.2 monographs and in Stanisław Grochowiak periodicals, such as Teksty Drugie and 1. Prace Literackie. The aim of this article is to present the alliance of sex and Co-editor of Słowacki power by looking at the phenomenon of “sexy Fascism.” i wiek XIX [Słowacki The notion was derived from Susan Sontag’s “Fascinat- and the Nineteenth ing Fascism.” In her essay, the American philosopher and Century], vol. 2 (2016). Contact: jakub- [email protected] 1 Tadeusz Borowski, This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen, trans. Barbara Vedder (New York: Penguin Books, 1976), 34. 2 Stanisław Grochowiak, Trismus, Prozy, ed. -

Pride and Powerlessness: Exploring Second Language Selection in Poland

PRIDE AND POWERLESSNESS: EXPLORING SECOND LANGUAGE SELECTION IN POLAND Leanne Marie Cameron B.A., California State University, Sacramento, 2006 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in TEACHING ENGLISH TO SPEAKERS OF OTHER LANGUAGES at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 © 2010 Leanne Marie Cameron ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii PRIDE AND POWERLESSNESS: EXPLORING SECOND LANGUAGE SELECTION IN POLAND A Thesis by Leanne Marie Cameron Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. John T. Clark __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Julian Heather ____________________________ Date iii Student: Leanne Marie Cameron I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Dr. Julian Heather TESOL Date Department of English iv Abstract of PRIDE AND POWERLESSNESS: EXPLORING SECOND LANGUAGE SELECTION IN POLAND by Leanne Marie Cameron In the past two hundred years, Poland twice labored under the brutal occupation of its stronger, militaristic neighbors, promoting anti-German and anti-Russian sentiment still visible today. This research study inquires as to whether these attitudes have any impact on the language selection of Polish university students. During November and December of 2009, four undergraduate English pedagogy students at a mid-level Polish university were interviewed in order to ascertain their attitudes toward the languages that they studied, the motivation for studying these languages, and the role of social pressure in becoming competent in English, German, or Russian. The results suggest that the subjects viewed English as a neutral, prestige language unconnected to a specific culture, be it American or British.