State of Access the Future of Roads on Public Lands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suspended-Sediment Concentration in the Sauk River, Washington, Water Years 2012-13

Prepared in cooperation with the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe Suspended-Sediment Concentration in the Sauk River, Washington, Water Years 2012-13 By Christopher A. Curran1, Scott Morris2, and James R. Foreman1 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Washington Water Science Center, Tacoma, Washington 2 Department of Natural Resources, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Darrington, Washington Photograph of glacier-derived suspended sediment entering the Sauk River immediately downstream of the Suiattle River mouth (August 5, 2014, Chris Curran). iii Introduction The Sauk River is one of the few remaining large, glacier-fed rivers in western Washington that is unconstrained by dams and drains a relatively undisturbed landscape along the western slope of the Cascade Range. The river and its tributaries are important spawning ground and habitat for endangered Chinook salmon (Beamer and others, 2005) and also the primary conveyors of meltwater and sediment from Glacier Peak, an active volcano (fig. 1). As such, the Sauk River is a significant tributary source of both fish and fluvial sediment to the Skagit River, the largest river in western Washington that enters Puget Sound. Because of its location and function, the Sauk River basin presents a unique opportunity in the Puget Sound region for studying the sediment load derived from receding glaciers and the potential impacts to fish spawning and rearing habitat, and downstream river-restoration and flood- control projects. The lower reach of the Sauk River has some of the highest rates of incubation mortality for Chinook salmon in the Skagit River basin, a fact attributed to unusually high deposition of fine-grained sediments (Beamer, 2000b). -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization And

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98503 In Reply Refer To: AUG 1 6 2011 13410-2011-F-0141 13410-2010-F-0175 Daniel M. Mathis, Division Adnlinistrator Federal Highway Administration ATIN: Jeff Horton Evergreen Plaza Building 711 Capitol Way South, Suite 501 Olympia, Washington 98501-1284 Michelle Walker, Chief, Regulatory Branch Seattle District, Corps of Engineers ATIN: Rebecca McAndrew P.O. Box 3755 Seattle, Washington 98124-3755 Dear Mr. Mathis and Ms. Walker: This document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion (Opinion) based on our review of the proposed State Route 20, Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization and Chronic Environmental Deficiency Project in Skagit County, Washington, and its effects on the bull trout (Salve linus conjluentus), marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), and designated bull trout critical habitat, in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) (Act). Your requests for initiation of formal consultation were received on February 3, 2011, and January 19,2010. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Seattle District (Corps) provided information in support of "may affect, likely to adversely affect" determinations for the bull trout and designated bull trout critical habitat. On April 13 and 14, 2011, the FHWA and Corps gave their consent for addressing potential adverse effects to the bull trout and bull trout critical habitat with a single Opinion. -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

Fishing in Washington Sportfishing Rules Pamphlet

NEWS RELEASE WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE 600 Capitol Way North, Olympia, Washington 98501-1091 Internet Address: http://wdfw.wa.gov May 23, 2008 Contact: Fish Program Customer Service, (360) 902-2700 WDFW issues clarifications and corrections to the 2008-09 Sportfishing Rules pamphlet OLYMPIA — The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) has issued corrections and clarifications to the recently published 2008-09 Fishing In Washington Sportfishing Rules pamphlet. The corrections and clarifications are also available on the department’s website at http://wdfw.wa.gov/fish/regs/fishregs.htm. WDFW will provide additional updates and corrections as needed. Anglers are advised to update their copies of the 2008-09 Fishing in Washington Sportfishing Rules pamphlet, which became effective May 1, 2008. Call the Fish Program Customer Service at (360) 902-2700 for questions regarding these changes. CORRECTIONS Page 19 – Grays Harbor Wild Coho Release Requirements Error: The release requirements listed for Grays Harbor Wild Coho are incorrect. Correction: The section should read: Anglers are required to release wild COHO in numerous Grays Harbor tributaries. For further information regarding release requirements of COHO in Marine Area 2.2, see page 108 of the 2008-09 Sportfishing Pamphlet. Page 44 – Cascade River (Skagit Co.) from mouth to Rockport-Cascade Rd. Bridge Error: The dates for the ALL SPECIES non-buoyant lure restriction and night closure are incorrect. Correction: The correct dates should read: ALL SPECIES - June 1-July 15 and Sept. 16- Nov. 30: non-buoyant lure restriction and night closure. Page 59 – Sauk River (Skagit/Snohomish Co.) from Whitechuck River upstream including NORTH FORK and SOUTH FORK Error: The description of this section of the river is incorrect. -

The Complete Script

Feb rua rg 1968 North Cascades Conservation Council P. 0. Box 156 Un ? ve rs i ty Stat i on Seattle, './n. 98 105 SCRIPT FOR NORTH CASCAOES SLIDE SHOW (75 SI Ides) I ntroduct Ion : The North Cascades fiountatn Range In the State of VJashington Is a great tangled chain of knotted peaks and spires, glaciers and rivers, lakes, forests, and meadov;s, stretching for a 150 miles - roughly from Pt. fiainier National Park north to the Canadian Border, The h undreds of sharp spiring mountain peaks, many of them still unnamed and relatively unexplored, rise from near sea level elevations to seven to ten thousand feet. On the flanks of the mountains are 519 glaciers, in 9 3 square mites of ice - three times as much living ice as in all the rest of the forty-eight states put together. The great river valleys contain the last remnants of the magnificent Pacific Northwest Rain Forest of immense Douglas Fir, cedar, and hemlock. f'oss and ferns carpet the forest floor, and wild• life abounds. The great rivers and thousands of streams and lakes run clear and pure still; the nine thousand foot deep trencli contain• ing 55 mile long Lake Chelan is one of tiie deepest canyons in the world, from lake bottom to mountain top, in 1937 Park Service Study Report declared that the North Cascades, if created into a National Park, would "outrank in scenic quality any existing National Park in the United States and any possibility for such a park." The seven iiiitlion acre area of the North Cascades is almost entirely Fedo rally owned, and managed by the United States Forest Service, an agency of the Department of Agriculture, The Forest Ser• vice operates under the policy of "multiple use", which permits log• ging, mining, grazing, hunting, wt Iderness, and alI forms of recrea• tional use, Hov/e ve r , the 1937 Park Study Report rec ornmen d ed the creation of a three million acre Ice Peaks National Park ombracing all of the great volcanos of the North Cascades and most of the rest of the superlative scenery. -

Middle Fork Snoqualmie River Watershed Access and Travel

United States Department Revised Environmental of Agriculture Assessment Forest Service January Middle Fork Snoqualmie River Watershed 2005 Access and Travel Management Plan and Forest Plan Amendment #20 Snoqualmie Ranger District, Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest For Information Contact: Team Leader: Doug Schrenk Snoqualmie Ranger District 42404 SE North Bend Way North Bend, WA 98045 (425) 888-1421, extension 233 [email protected] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Page i Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 - PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION -- BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................... 1 CHANGED CONDITIONS -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES October-November 1969 2 THE WILD CASCADES FARTHEST EAST: CHOPAKA MOUNTAIN Field Notes of an N3C Reconnaissance State of Washington, school lands managed by May 1969 the Department of Natural Resources. The absolute easternmost peak of the North Cascades is Chopaka Mountain, 7882 feet. An This probably is the most spectacular chunk abrupt and impressive 6700-foot scarp drops of alpine terrain owned by the state. Certain from the flowery summit to blue waters of ly its fame will soon spread far beyond the Palmer Lake and meanders of the Similka- Okanogan. Certainly the state should take a mean River, surrounded by green pastures new, close look at Chopaka and develop a re and orchards. Beyond, across this wide vised management plan that takes into account trough of a Pleistocene glacier, roll brown the scenic and recreational resources. hills of the Okanogan Highlands. Northward are distant, snowy beginnings of Canadian ranges. Far south, Tiffany Mountain stands above forested branches of Toats Coulee Our gang became aware of Chopaka on the Creek. Close to the west is the Pasayten Fourth of July weekend of 1968 while explor Wilderness Area, dominated here by Windy ing Horseshoe Basin -- now protected (except Peak, Horseshoe Mountain, Arnold Peak — from Emmet Smith's cattle) within the Pasay the Horseshoe Basin country. Farther west, ten Wilderness Area. We looked east to the hazy-dreamy on the horizon, rise summits of wide-open ridges of Chopaka Mountain and the Chelan Crest and Washington Pass. were intrigued. To get there, drive the Okanogan Valley to On our way to Horseshoe Basin we met Wil Tonasket and turn west to Loomis in the Sin- lis Erwin, one of the Okanoganites chiefly lahekin Valley. -

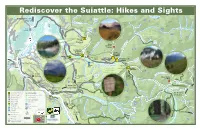

Rediscover the Suiattle: Hikes and Sights

Le Conte Chaval, Mountain Rediscover the Suiattle:Mount Hikes and Sights Su ia t t l e R o Crater To Marblemount, a d Lake Sentinel Old Guard Hwy 20 Peak Bi Buckindy, Peak g C reek Mount Misch, Lizard Mount (not Mountain official) Boulder Boat T Hurricane e Lake Peak Launch Rd na Crk s as C en r G L A C I E R T e e Ba P E A K k ch e l W I L D E R N E S S Agnes o Mountain r C Boulder r e Lake e Gunsight k k Peak e Cub Trailhead k e Dome e r Lake Peak Sinister Boundary e C Peak r Green Bridge Put-in C y e k Mountain c n u Lookout w r B o e D v Darrington i Huckleberry F R Ranger S Mountain Buck k R Green Station u Trailhead Creek a d Campground Mountain S 2 5 Trailhead Old-growth Suiattle in Rd Mounta r Saddle Bow Grove Guard een u Gr Downey Creek h Mountain Station lp u k Trailhead S e Bannock Cr e Mountain To I-5, C i r Darrington c l Seattle e U R C Gibson P H M er Sulphur S UL T N r S iv e uia ttle R Creek T e Falls R A k Campground I L R Mt Baker- Suiattle d Trailhead Sulphur Snoqualmie Box ! Mountain Sitting Mountain Bull National Forest Milk n Creek Mountain Old Sauk yo Creek an North Indigo Bridge C Trailhead To Suiattle Closure Lake Lime Miners Ridge White Road Mountain No Trail Chuck Access M Lookout Mountain M I i Plummer L l B O U L D E R Old Sauk k Mountain Rat K Image Universal C R I V E R Trap Meadow C Access Trail r Lake Suiattle Pass Mountain Crystal R e W I L D E R N E S S e E Pass N Trailhead Lake k Sa ort To Mountain E uk h S Meadow K R id Mountain T ive e White Chuck Loop Hwy ners Cre r R i ek R M d Bench A e Chuc Whit k River I I L Trailhead L A T R T Featured Trailheads Land Ownership S To Holden, E Other Trailheads National Wilderness Area R Stehekin Fire C Mountain Campgrounds National Forest I C Beaver C I F P A Fortress Boat Launch State Conservation Lake Pugh Mtn Mountain Trailhead Campground Other State Road Helmet Butte Old-growth Lakes Mt. -

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory by Molly Sue Malone B.A., Dartmouth College, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Molly Sue Malone, 2013 Abstract Upper Skagit Indian Tribe are a Coast Salish fishing community in western Washington, USA, who face the challenge of remaining culturally distinct while fitting into the socioeconomic expectations of American society, all while asserting their rights to access their aboriginal territory. This dissertation asks a twofold research question: How do Upper Skagit people interact with and experience the aquatic environment of their aboriginal territory, and how do their experiences with colonization and their cultural practices weave together to form a historical consciousness that orients them to their lands and waters and the wider world? Based on data from three methods of inquiry—interviews, participant observation, and archival research—collected over sixteen months of fieldwork on the Upper Skagit reservation in Sedro-Woolley, WA, I answer this question with an ethnography of the interplay between culture, history, and the land and waterscape that comprise Upper Skagit aboriginal territory. This interplay is the process of historical consciousness, which is neither singular nor sedentary, but rather an understanding of a world in flux made up of both conscious and unconscious thoughts that shape behavior. I conclude that the ways in which Upper Skagit people interact with what I call the waterscape of their aboriginal territory is one of their major distinctive features as a group. -

Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-78 Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound July 2006 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, uses the NOAA Techni- cal Memorandum NMFS series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible due to time constraints. Documents published in this series may be referenced in the scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-NWFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS- F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest & Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which has since been split into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The NMFS-AFSC Techni- cal Memorandum series is now being used by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. This document should be cited as follows: Ruckelshaus, M.H., K.P. Currens, W.H. Graeber, R.R. Fuerstenberg, K. Rawson, N.J. Sands, and J.B. Scott. 2006. Independent populations of Chinook salmon in Puget Sound. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-NWFSC-78, 125 p. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-78 Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound Mary H. Ruckelshaus,