Steeleye Span 1997 Tour Programme Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

The History of Rock, a Monthly Magazine That Reaps the Benefits of Their Extraordinary Journalism for the Reader Decades Later, One Year at a Time

L 1 A MONTHLY TRIP THROUGH MUSIC'S GOLDEN YEARS THIS ISSUE:1969 STARRING... THE ROLLING STONES "It's going to blow your mind!" CROSBY, STILLS & NASH SIMON & GARFUNKEL THE BEATLES LED ZEPPELIN FRANK ZAPPA DAVID BOWIE THE WHO BOB DYLAN eo.ft - ink L, PLUS! LEE PERRY I B H CREE CE BEEFHE RT+NINA SIMONE 1969 No H NgWOMI WI PIK IM Melody Maker S BLAST ..'.7...,=1SUPUNIAN ION JONES ;. , ter_ Bard PUN FIRS1tintFaBil FROM 111111 TY SNOW Welcome to i AWORD MUCH in use this year is "heavy". It might apply to the weight of your take on the blues, as with Fleetwood Mac or Led Zeppelin. It might mean the originality of Jethro Tull or King Crimson. It might equally apply to an individual- to Eric Clapton, for example, The Beatles are the saints of the 1960s, and George Harrison an especially "heavy person". This year, heavy people flock together. Clapton and Steve Winwood join up in Blind Faith. Steve Marriott and Pete Frampton meet in Humble Pie. Crosby, Stills and Nash admit a new member, Neil Young. Supergroups, or more informal supersessions, serve as musical summit meetings for those who are reluctant to have theirwork tied down by the now antiquated notion of the "group". Trouble of one kind or another this year awaits the leading examples of this classic formation. Our cover stars The Rolling Stones this year part company with founder member Brian Jones. The Beatles, too, are changing - how, John Lennon wonders, can the group hope to contain three contributing writers? The Beatles diversification has become problematic. -

Download PDF Booklet

“I am one of the last of a small tribe of troubadours who still believe that life is a beautiful and exciting journey with a purpose and grace well worth singing about.” E Y Harburg Purpose + Grace started as a list of songs and a list of possible guests. It is a wide mixture of material, from a traditional song I first heard 50 years ago, other songs that have been with me for decades, waiting to be arranged, to new original songs. You stand in a long line when you perform songs like this, you honour the ancestors, but hopefully the songs become, if only briefly your own, or a part of you. To call on my friends and peers to make this recording has been a great pleasure. Turning the two lists into a coherent whole was joyous. On previous recordings I’ve invited guest musicians to play their instruments, here, I asked singers for their unique contributions to these songs. Accompanying song has always been my favourite occupation, so it made perfect sense to have vocal and instrumental collaborations. In 1976 I had just released my first album and had been picked up by a heavy, old school music business manager whose avowed intent was to make me a star. I was not averse to the concept, and went straight from small folk clubs to opening shows for Steeleye Span at the biggest halls in the country. Early the next year June Tabor asked me if I would accompany her on tour. I was ecstatic and duly reported to my manager, who told me I was a star and didn’t play for other people. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

Dypdykk I Musikkhistorien - Del 27: Folkrock (25.11.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 03.03.2020

Dypdykk i musikkhistorien - Del 27: Folkrock (25.11.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 03.03.2020 Spilleliste pluss noen ekstra lyttetips: [Bakgrunnsmusikk: Resor och näsor (Under solen lyser solen (2001) / Grovjobb)] Starten Beatles og British invasion The house of the rising sun (The house of the rising sun (1964, singel) / Animals) Mr. Tambourine Man (Mr. Tambourine Man (1965) / Byrds) Candy man ; The Devil's got my woman (Candy man (1966, singel) / Rising Sons) Maggies farm Bob Dylan Live at the Newport Folk Festival USA One-way ticket ; The falcon ; Reno Nevada Celebrations For A Grey Day (1965) / Mimi & Richard Fariña From a Buick 6 (Highway 61 revisited (1965) / Bob Dylan) Sounds of silence (Sounds of silence (1966) / Simon & Garfunkel) Hard lovin’ looser (In my life (1966) / Judy Collins) Like a rolling stone (Live 1966 (1998) / Bob Dylan) 1 Eight miles high (Fifth Dimension (1966) / The Byrds) It’s not time now ; There she is (Daydream (1966) / The Lovin’ Spoonful) Jefferson Airplane takes off (1966) / Jefferson Airplane Carnival song ; Pleasant Street Goodbye And Hello (1967) / Tim Buckley Pleasures Of The Harbor (1967) I Phil Ochs Virgin Fugs (1967) / The Fugs Alone again or (Forever changes (1967) / Love) Morning song (One nation underground (1967) / Pearls Before Swine) Images of april (Balaklava (1968) / Pearls Before Swine) Rainy day ; Paint a lady (Paint a lady (1970) / Susan Christie) Country rock Buffalo Springfield Taxim (A beacon from Mars (1968) / Kaleidoscope) Little hands (Oar (1969) / Skip Spence) Carry on Deja vu (1970) / Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young 2 Britisk Donovan Sunshine superman (1966) The river song ; Jennifer Juniper The Hurdy Gurdy Man (1968) You know what you could be (The 5000 spirits or the layers of the onion (1967) / The Incredible String Band) Astral weeks (1968) / Van Morrison Child star (My People Were Fair And Had Sky In Their Hair.. -

Beyond the Bog Road Eileen Ivers and Immigrant Soul

HOT SEASON FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 2012-2013 TEACHER GUIDEBOOK Beyond the Bog Road Eileen Ivers and Immigrant Soul Photo by Luke Ratray Regions Bank A Note from our Sponsor For over 125 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production with- out this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in ad- dition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. Thank you, teachers, for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy the experience. You are creating memories of a lifetime, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this op- portunity possible. Jim Schmitz Executive Vice President Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area Dear Teachers, It would be easy to say that Eileen Ivers and Immigrant Soul – an ensemble led by a Celtic fiddler who is one of the original performers in both Riverdance and Table of Contents Cherish the Ladies – is an Irish-American band. Considering the popularity of Irish music in our country Irish Music Timeline (2) these days, that would also make good marketing sense. -

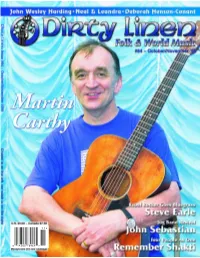

14302 76969 1 1>

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

May 6, 1,78 15P

May 6, 1,78 15p o . a racwru M111,11, T, wrey v, aa 1/K SIMr, USSINQIES USALBUMS (IKALBuMS 1 1 1 1 SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER. Soundtrack RSO 1 2 NIGHT FEVER, Bea Gees RSO NIGHT FEVER, Bee Gees RSO 1 2 SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER. Various RSO 2 3 LONDON TOWN, Wings Cadrol -2 1 MATCHSTALK MEN 6 CATS 6 DOGS, Brien b Michael Pye 2 2 IF I CAN'T HAVE YOU, Yvonne Elliman RSO 2 1 20 GOLDEN GREATS, Nat King Cole Capitol 3 2 SLOWHAND, Eric Clanton RSO 3 3 I WONDER WHY, Showeddhi-adds 3 3 CAN'T SMILE WITHOUT YOU. Barry Manblow Arista Anne 3 3 AND THEN THERE WERE THREE, Genesis Charisma 4 B POINT OF KNOWNETURN, Kansas Kirshner 4 4 4 4 THE I Atlantic IF YOU CAN'T GIVE ME LOVE, Seal Ouatro RAK 4 1 CLOSER GET TO YOU, Roberta Flack 4 LONDON TOWN, Wings Pariophone 5 7 EARTH. JEFFERSON STARSHIP, Jefferson Starlhip Grunt 5 7 TOO MUCH TOO TOO 5 5 WITH A LITTLE LUCK, Wings Capitol LITTLE LATE, Johnny Mathis CBS 5 5 THE ALBUM, Abbe Epic 4 Billy Joel Columbia 6 5 NEVER LET HER SUP AWAY. Andrew Gold Asylum 6 10 TOO MUCH, TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE, Johnny Mathis Columbia 6 THE STRANGER, 6 10 THE STUD, Various Ronco 7 5 WEEKEND IN LA, George Benson Warner Bros 7 9 FOLLOW YOU FOLLOW ME. Genesis Chadarne 7 9 YOU'RE THE ONE THAT I WANT, John Travolte RSO 7 - LONG LIVE ROCK 'N' ROLL, Rainbow Polydor B 10 RUNNING ON EMPTY, Jackson Browne Aaylum 8 5 WITH A LITTLE LUCK, Wings Padoohone 8 8 LAY DOWN ESO 8 18 YOU LIGHT UP MY LIFE, Johnny Mathis CBS SALLY, Eric Clacton 9 13 FEELS SO GOOD, Chuck Mangler, AeN 9 8 BAKER STREET, Gem Rafferty United Anise 9 7 DUSTIN THE WIND, Kenning Kirshner 9 B CITY TO CITY, Gerry Rafferty United Artists 12 BOY. -

Season Brochure 2013 25/02/2013 07:27 Page 1

Hever 2013 Brochureware_Season Brochure 2013 25/02/2013 07:27 Page 1 BOX OFFICE 01732 866114 www.heverfestival.co.uk SUMMER FESTIVAL 2013 A Perfect Summer’s Evening FestivalThe Theatre atHEVER CASTLE Hever 2013 Brochureware_Season Brochure 2013 25/02/2013 07:27 Page 2 Email - [email protected] Book online at www.heverfestival-tickets.co.uk THEATRE INFORMATION Food and Drink Pre Theatre Suppers are available in the Guthrie Pavilion on the evening of all performances,* with access to the Castle grounds for those who have booked ahead from 5.45 pm. A snack food counter and bar are also available pre-performance and during the interval. * Please note that Levy Restaurants reserves the right to cancel pre-theatre suppers should there be no advance bookings 3 days prior to the event. Special Events Family Feast – served after all childrens shows: Babe the Sheep-Pig on 30 – 31 May & The Wind in the Willows on 30 – 31 July. Dinner served at 4.45pm in the Guthrie Pavilion following the performance. Cream Teas – served after both matinee performances: Joking Apart on Thursday 25th July & The Taming of the Shrew on Friday 30 August. Served at 4.30pm in the Guthrie Pavilion following the performance. Menus for all Special Events and Pre Theatre Suppers are available on our website. To make a reservation, please call the Box Office on 01732 866114. Please note, special events must be paid for at the time of booking. Accommodation Hever Castle offers Luxury B&B, which was voted 9 out of 10 by The Telegraph Travel’s Section Hotelwatch Review in June 2012. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center, our multimedia, folk-related archive). All recordings received are included in Publication Noted (which follows Off the Beaten Track). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention Off The Beaten Track. Sincere thanks to this issues panel of musical experts: Roger Dietz, Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Andy Nagy, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Elijah Wald, and Rob Weir. liant interpretation but only someone with not your typical backwoods folk musician, Jodys skill and knowledge could pull it off. as he studied at both Oberlin and the Cin- The CD continues in this fashion, go- cinnati College Conservatory of Music. He ing in and out of dream with versions of was smitten with the hammered dulcimer songs like Rhinordine, Lord Leitrim, in the early 70s and his virtuosity has in- and perhaps the most well known of all spired many players since his early days ballads, Barbary Ellen. performing with Grey Larsen. Those won- To use this recording as background derful June Appal recordings are treasured JODY STECHER music would be a mistake. I suggest you by many of us who were hearing the ham- Oh The Wind And Rain sit down in a quiet place, put on the head- mered dulcimer for the first time.