Jazz: New Orleans 1885-1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

In 191^B Played His First Professional Job. He Bought a Sax on August 3/ and Played His First Job on September 3

PAUL BARNES 1 Reel I [of 2]--Digest-Retype June 16, 1969 Also present; Barry Martyn, Lars Edegran/ Richard B. Alien Paul Daniel Barnes, whose professional name is "Polo" Barnes/ was born November 22, 1903., in New Orleans/ Louisiana. When he was six years old, he started playing a ten cent [tin] fife. This kind of fife was popular in New Orleans. George Lewis, [Emil-e] Barnes and Sidney ^. Bechet and many others also started on the fife. In 191^B played his first professional job. He bought a sax on August 3/ and played his first job on September 3. He had a foundation from playing the fife. As a kid, he played Emile Barnes' clarinet. There were few Boehm system clarinetists then. 'PB now plays a Boehm. Around 1920 PB started playing a Boehm system clarinet, but he couldn't get the hang of it/ so he went back to the sax/ which he played until he got with big bands. He took solos on the soprano sax [and later alto sax], but not on the clarinet. He is largely self-taught. He tooT< three or four saxophone lessons from Lorenzo Tie [Jr.]. Tio was always high. PB learned clarinet from Emile Barnes. PB wanted to play like Sidney Bechet, but he couldn't get the tone. PB played tenor sax around New York/ baritone sa^( [and still occasionally alto]. [Today PB is still playing clarinet almost exclusively--RBA, June 7, 1971<] His first organized band was PB's and Lawrence Marrero's Original Diamond Orchestra. It had Bush Hall, tp/ replaced by Red Alien; Cie Frazier [d]; Lawrence [Marrero] / [bj?]. -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

A Researcher's View on New Orleans Jazz History

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Format 6 New Orleans Jazz 7 Brass & String Bands 8 Ragtime 11 Combining Influences 12 Party Atmosphere 12 Dance Music 13 History-Jazz Museum 15 Index of Jazz Museum 17 Instruments First Room 19 Mural - First Room 20 People and Places 21 Cigar maker, Fireman 21 Physician, Blacksmith 21 New Orleans City Map 22 The People Uptown, Downtown, 23 Lakefront, Carrollton 23 The Places: 24 Advertisement 25 Music on the Lake 26 Bandstand at Spanish Fort 26 Smokey Mary 26 Milneburg 27 Spanish Fort Amusement Park 28 Superior Orchestra 28 Rhythm Kings 28 "Sharkey" Bonano 30 Fate Marable's Orchestra 31 Louis Armstrong 31 Buddy Bolden 32 Jack Laine's Band 32 Jelly Roll Morton's Band 33 Music In The Streets 33 Black Influences 35 Congo Square 36 Spirituals 38 Spasm Bands 40 Minstrels 42 Dance Orchestras 49 Dance Halls 50 Dance and Jazz 51 3 Musical Melting Pot-Cotton CentennialExposition 53 Mexican Band 54 Louisiana Day-Exposition 55 Spanish American War 55 Edison Phonograph 57 Jazz Chart Text 58 Jazz Research 60 Jazz Chart (between 56-57) Gottschalk 61 Opera 63 French Opera House 64 Rag 68 Stomps 71 Marching Bands 72 Robichaux, John 77 Laine, "Papa" Jack 80 Storyville 82 Morton, Jelly Roll 86 Bolden, Buddy 88 What is Jazz? 91 Jazz Interpretation 92 Jazz Improvising 93 Syncopation 97 What is Jazz Chart 97 Keeping the Rhythm 99 Banjo 100 Violin 100 Time Keepers 101 String Bass 101 Heartbeat of the Band 102 Voice of Band (trb.,cornet) 104 Filling In Front Line (cl. -

The Origin of Armstrong's Hot Fives and Hot Sevens Gene H

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Faculty Publications Music 2003 The Origin of Armstrong's Hot Fives and Hot Sevens Gene H. Anderson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/music-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Gene H. "The Origin of Armstrong's Hot Fives and Hot Sevens." College Music Symposium 43 (2003): 13-24. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Originof Armstrong's Hot Fives and Hot Sevens Gene Anderson has been almostfifty years since Louis Armstrong'sHot Five and Hot Seven ecordingsof 1925-19281were first recognized in print as a watershedof jazz history andthe means by which the trumpeter emerged as thestyle's first transcendent figure.2 Sincethen these views have only intensified. The Hot Fives and Hot Sevens have come to be regardedas harbingersof all jazz since,with Armstrong's status as the"single mostcreative and innovative force in jazz history"and an "Americangenius" now well beyonddispute.3 This study does notquestion these claims but seeks, rather, to deter- minethe hitherto uninvestigated origin of such a seminalevent and to suggestthat Armstrong'sgenius was presentfrom the beginning of the project. /:Historical Background The seedsof the idea thatgerminated into the Hot Five and Hot Sevenmay have been sownin theearly morning hours of June8, 1923 at theConvention of Applied MusicTrades in Chicago'sDrake Hotel. -

Mss 520 the William Russell Photographic Collection 1899-1992 Ca

Mss 520 The William Russell Photographic Collection 1899-1992 Ca. 6200 items Scope and Content Note: The William Russell Photographic Collection spans almost a century of jazz history, from Buddy Bolden’s band to the George Lewis Trio to the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra. It is also a valuable resource in other areas of New Orleans cultural history. It includes photographs, both ones Russell took and those taken by others. Russell was interested in a complete documentation of jazz and the world it grew out of. He collected early photographs of some of the first performers of what became jazz, such as Emile Lacoume’s Spasm Band, and took photographs (or asked others to do so) of performers he met between 1939 and his death in 1992. These photographs show the musicians performing at Preservation Hall or in concert, marching in parades or jazz funerals, and at home with family and pets. He was also interested in jazz landmarks, and kept lists of places he wanted to photograph, the dance halls, nightclubs and other venues where jazz was first performed, the homes of early jazz musicians such as Buddy Bolden, and other places associated with the musicians, such as the site of New Orleans University, an African-American school which Bunk Johnson claimed as his alma mater. He took his own photographs of these places, and lent the lists to visiting jazz fans, who gave him copies of the photographs they took. Many of these locations, particularly those in Storyville, have since been torn down or altered. After Economy Hall was badly damaged in hurricane Betsy and San Jacinto Hall in a fire, Russell went back and photographed the ruins. -

Versing the Ghetto: African American Writers and the Urban Crisis By

Versing the Ghetto: African American Writers and the Urban Crisis By Malcolm Tariq A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Awkward, Co-Chair Associate Professor Megan Sweeney, Co-Chair Associate Professor Matthew Countryman Professor Susan Scotti Parrish Malcolm Tariq [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8908-544X © Malcolm Tariq 2018 This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother —Marilyn T. Furman— who brought us up at the end of a street. ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed graduate school or this dissertation without the light of my family and friends. I’m most thankful for my parents for giving me the tools to conquer all and the rest of my family whose love and support continue to drive me forward. I wouldn’t have survived the University of Michigan or Ann Arbor were it not for the House (Gabriel Sarpy, Michael Pascual, Faithe Day, Cassius Adair, and Meryem Kamil). I will forever remember house parties and sleepovers and potlucks and Taco Bell and Popeyes and running the town into complete chaos. Ann Arbor didn’t know what to do with us. Thank you for inspiring my crazy and feeding my soul those dark Midwestern years. I am, as always, profoundly indebted to the Goon Squad (Marissa, Jayme, Tyler, Ish, Hanna, Shriya, Bianca, Amaad, Nikki, Ankita, and Rahul), to whom I owe too much. You have taught me lightyears beyond what the classrooms of Emory University gave us. -

Collection of Jazz Articles

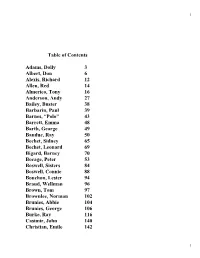

1 Table of Contents Adams, Dolly 3 Albert, Don 6 Alexis, Richard 12 Allen, Red 14 Almerico, Tony 16 Anderson, Andy 27 Bailey, Buster 38 Barbarin, Paul 39 Barnes, “Polo” 43 Barrett, Emma 48 Barth, George 49 Bauduc, Ray 50 Bechet, Sidney 65 Bechet, Leonard 69 Bigard, Barney 70 Bocage, Peter 53 Boswell, Sisters 84 Boswell, Connie 88 Bouchon, Lester 94 Braud, Wellman 96 Brown, Tom 97 Brownlee, Norman 102 Brunies, Abbie 104 Brunies, George 106 Burke, Ray 116 Casimir, John 140 Christian, Emile 142 1 2 Christian, Frank 144 Clark, Red 145 Collins, Lee 146 Charles, Hypolite 148 Cordilla, Charles 155 Cottrell, Louis 160 Cuny, Frank 162 Davis, Peter 164 DeKemel, Sam 168 DeDroit, Paul 171 DeDroit, John 176 Dejan, Harold 183 Dodds, “Baby” 215 Desvigne, Sidney 218 Dutrey, Sam 220 Edwards, Eddie 230 Foster, “Chinee” 233 Foster, “Papa” 234 Four New Orleans Clarinets 237 Arodin, Sidney 239 Fazola, Irving 241 Hall, Edmond 242 Burke, Ray 243 Frazier, “Cie” 245 French, “Papa” 256 Dolly Adams 2 3 Dolly‟s parents were Louis Douroux and Olivia Manetta Douroux. It was a musical family on both sides. Louis Douroux was a trumpet player. His brother Lawrence played trumpet and piano and brother Irving played trumpet and trombone. Placide recalled that Irving was also an arranger and practiced six hours a day. “He was one of the smoothest trombone players that ever lived. He played on the Steamer Capitol with Fats Pichon‟s Band.” Olivia played violin, cornet and piano. Dolly‟s uncle, Manuel Manetta, played and taught just about every instrument known to man. -

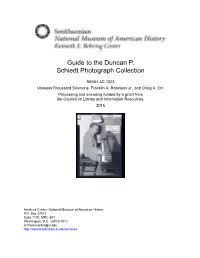

Guide to the Duncan P. Schiedt Photograph Collection

Guide to the Duncan P. Schiedt Photograph Collection NMAH.AC.1323 Vanessa Broussard Simmons, Franklin A. Robinson Jr., and Craig A. Orr. Processing and encoding funded by a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources. 2016 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Background Information and Research Materials, 1915-2012, undated..................................................................................................................... 4 Series 2: Photographic Materials, 1900-2012,