The Hum of Distant Novas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pentagon's UAP Task Force

The Pentagon’s UAP Task Force Franc Milburn Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 183 THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 183 The Pentagon’s UAP Task Force Franc Milburn The Pentagon’s UAP Task Force Franc Milburn © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 November 2020 Cover image: Screen capture of US Navy footage of an Unidentified Aerial Phenomenon, US Department of Defense The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies is an independent, non-partisan think tank conducting policy-relevant research on Middle Eastern and global strategic affairs, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and regional peace and stability. It is named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace laid the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. In sponsoring these discussions, the BESA Center aims to stimulate public debate on, and consideration of, contending approaches to problems of peace and war in the Middle East. -

Unidentified: Inside America's Ufo Investigation with Tom

UNIDENTIFIED: INSIDE AMERICA’S UFO INVESTIGATION WITH TOM DELONGE Series 2 NEW AND EXCLUSIVE SERIES RETURNS ON HISTORY® MÅNDAGAR FRÅN 26 OKTOBER KL 21.00 (8x1) INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE ON REQUEST (Canal Digital | Com Hem | Boxer | Viasat | Telia | Telenor | Sappa | IP Sweden | Sydantenn) Website: http://www.historytv.se Facebook: facebook.com/HISTORYSverige Instagram: instagram.com/HISTORYSve Download preview clip HERE Comic Con interview “It's not often a new television series gets the U.S. government to cough up its long- held secrets. That's exactly what happened after Unidentified: Inside America’s UFO Investigation aired…” SYFY Following the recently released Pentagon UFO videos, former Blink 182 star, Tom DeLonge (pictured left) returns to HISTORY for a brand-new series of Unidentified: Inside America’s UFO investigation. In season two each episode follows a specific case of the Pentagon’s U.F.O. Task Force, the Unidentified Aerial Phenomenon (UAP) which according to The New York Times will standardise collection and reporting on sightings of unexplained aerial vehicles, and report findings to the public every six months, following a recent Senate Committee Report. Investigators followed in the series include former military intelligence official and Special Agent In-Charge, Luis Elizondo (pictured right), and former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defence and Intelligence, Chris Mellon. The team continue to divulge what the US government know about these bizarre craft, hear additional first-hand eyewitness accounts of UAP sightings from military and civilian personnel, and share insight and information about these craft to produce tangible evidence and build the most indisputable case for the existence and threat of UAP ever assembled. -

CONTACT in the DESERT SPECIAL Featuring: Linda Moulton Howe, James Gilliland, John Desouza, Jeremy Corbell, Stephen Bassett

A BRAND NEW MAGAZINE ON UFOLOGY & ALTERNATIVE THINKING TOP 10 ANCIENT SITES OF THE AMERICAS ISSUE #3 APR/MAY 2018 CONTACT IN THE DESERT SPECIAL Featuring: Linda Moulton Howe, James Gilliland, John DeSouza, Jeremy Corbell, Stephen Bassett OUT OF BODY EXPERIENCES What are they and how not to freak out if it happens to you! THE CULROSS WITCH TRIALS 50 years before Salem, accusations abound in Scotland. S-4 DIGITAL PRESS Plus more great interviews and features inside! EDITOR’S LETTER WELCOME! “Humans…[sigh] Hillbilllies of the Universe.” Ildis Kitan, The Orville, S1 E8 (2017) ust as this issue was in the flying high on Netflix. We also had a final stages, we learned of the fascinating chat with ex-FBI Special Jpassing of a true alternative Agent John DeSouza about his radio legend - Art Bell. The founder investigations into the paranormal and original host of the ultra- and Preston Dennett gave us his popular CoastToCoastAM had been guide to Out Of Body Experiences, ill for some time and you can read which we fully intend to follow when our tribute to the great man over we get five minutes! the page. With researchers Jim Marrs and John Anthony West also I’d like to extend hearty thanks to passing within the last 12 months, the incredibly talented Erik Stitt, and Graham Hancock having a near who provided our beautiful cover miss as well, it seems the alternative image. Erik is a lifelong experiencer community has taken a bit of a hit and channeller and has also of late. It is therefore important generously provided a signed copy people can get together with like- of the artwork, to be given away minded individuals who supported free to one lucky reader - see page the work of Art, et al. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

Ufos Real? to Roswell, New Mexico, and Attended a Conference Explore Eyewitness Accounts, Examine the Put on by the Mutual UFO Network

HALLS KELLY MILNER HALLS is a full- time author with a passion for unearthing unusual facts about the creatures and the world around her. She loves to dig up the details by interviewing experts and discovering the most up-to-date research on her subjects. In her research for this book, she traveled Are aliens and UFOs real? to Roswell, New Mexico, and attended a conference Explore eyewitness accounts, examine the put on by the Mutual UFO Network. Her previous evidence, and decide for yourself. books include Tales of the Cryptids: Mysterious Creatures That May or May Not Exist, Mysteries of the Mummy Kids, Saving the Baghdad Zoo, and In Search of Sasquatch. Halls lives with her two daughters in Spokane, Washington. You can find out more about IMAGINE . INVESTIGATION her and her books at www.kellymilnerhalls.com. you’re in the woods after dark. Eerie green lights appear in the distance. Then there’s a sudden flash and everything is dark again. You decide to take a closer look. You come upon a saucer-shaped craft hovering silently just above the ground. You reach out to touch it, but the object suddenly shoots up into the sky. Have you just seen a UFO? Some people say they have had experiences like “Through her outstanding research O phenomena and her clear and on UF this. Are they telling the truth? To find out, Kelly understandable writing style, Kelly Milner Milner Halls investigated stories of eyewitnesses Halls has skillfully revealed the detailsO ofs.” from around the world. She explored UFO sightings, some of the most famous and important UFO cases in the world. -

Literatura Y Otras Artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and His Multiple Identities »

TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO « Literatura y otras artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and his multiple identities » Autor: Juan Muñoz De Palacio Tutor: Rafael Vélez Núñez GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Curso Académico 2014-2015 Fecha de presentación 9/09/2015 FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD DE CÁDIZ INDEX INDEX ................................................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARIES AND KEY WORDS ........................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 1. HIP HOP ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. THE 4 ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 8 1.2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................. 10 1.3. WORLDWIDE RAP ............................................................................................................. 21 2. EMINEM ................................................................................................................. 25 2.1. BIOGRAPHICAL KEY FEATURES ............................................................................................. 25 2.2 RACE AND GENDER CONFLICTS ........................................................................................... -

Offering Circular Dated September 29, 2017

Filed pursuant to Rule 253(g)(2) File No. 024-10728 OFFERING CIRCULAR DATED SEPTEMBER 29, 2017 To The Stars Academy of Arts and Science Inc. 1051 S. Coast Hwy 101 Suite B Encinitas, CA 92024 760.452.8702 Up to 10,000,000 shares of Class A Common Stock SEE “SECURITIES BEING OFFERED” AT PAGE 38 Underwriting discount and Proceeds to Proceeds to Price to Public commissions issuer* other persons Per share/unit $ 5.00 N/A $ 5.00 N/A Total Minimum $ 1,000,000 N/A $ 1,000,000 N/A Total Maximum $ 50,000,000 N/A $ 50,000,000 N/A *We expect that the expenses of the offering will be approximately $250,000 if the minimum number of shares are sold in this offering and approximately $6,500,000 if the maximum number of shares are sold in this offering. See the “Plan of Distribution and Selling Securityholders” for details. This offer will terminate at the earlier of (1) the date at which the maximum offering amount of $50,000,000 has been sold, (2) September 29, 2018, or (3) the date at which the offering is earlier terminated by the company at its sole discretion. See “Plan of Distribution.” The company has engaged Prime Trust, LLC as escrow agent to hold any funds that are tendered by investors in accordance with Rule 15c2-4 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. Investor funds will be held in a segregated bank account at an FDIC insured bank pending closing or termination of the offering. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

Current Strategic Business Plan for the Implementation of Digital

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 968 EC 309 831 Current Strategic Business Plan for the Implementation of TITLE Digital Systems. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 2003-12-00 NOTE 245p. AVAILABLE FROM Reference Section, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20542. For full text: http://www.loc.gov.html. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer System Design; Library Networks ABSTRACT This document presents a current strategic business plan for the implementation of digital systems and servicesfor the free national library program operated by the National LibraryService for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, its networkof cooperating regional and local libraries, and the United StatesPostal Service. The program was established in 1931 and isfunded annually by Congress. The plan will be updated and refined as supporting futurestudies are completed. (AMT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ., . I a I a a a p , :71110i1 aafrtexpreve ..4111 AAP"- .4.011111rAPrip -"" Al MI 1111 U DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Oth of Educattonal Research and Improvement ED ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION .a.1111PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND CENTER (ERIC) DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS IN" This document has been reproduced as BEEN GRANTED BY received from the person -

The Drake Equation

The Drake Equation The Drake equation, which we encountered in the very first lecture of this class, is a way to take the question “How many communicative civilizations are there currently in our galaxy?” and break it into several factors that we estimate as best we can. In this class we will go into detail about this equation. We will find that we now have a decent idea of the values of a couple of the factors, but that many are still guesswork. We’ll do our best to make our guesses informed. We will also discover that some people have reformulated the equation by adding a number of other factors they consider crucial to having technologically adept life. The remarkable and subtle effect of this is that, depending on how many factors you think appropriate, you can get the conclusions you want while appearing reasonable and conservative throughout. That is, if you think many civilizations exist, you can use the Drake equation to demonstrate this. If you think we are the only ones, you can get the equation to say that as well. With this in mind, we should approach the Drake equation as a way of framing our discussion as opposed to as a method of determining the answer rigorously. The equation itself and its factors The original form of the equation was written by Frank Drake in 1960 in preparation for a meeting in Green Bank, West Virginia. It says: ∗ N = R × fp × ne × fl × fi × fc × L . (1) Here: • N is the number of currently active, communicative civilizations in our galaxy. -

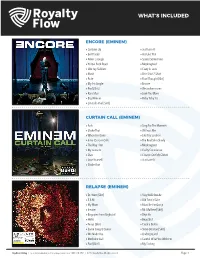

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

Eminem, Like Toy Soldiers Step by Step

Eminem, Like Toy Soldiers Step by step... heart to heart... left right left We all fall down CHORUS Step by step, heart to heart, left right left We all fall down, like toy soldiers Bit by bit, torn apart, we never win But the battle wages on, for toy soldiers I'm supposed to be the soldier who never blows his composure Even though I hold the weight of the whole world on my shoulders I ain't never supposed to show it, my crew ain't supposed to know it But if it means going toe to toe with the Benzino, it don't matter I'd never drag 'em in battles that I can handle 'less I absolutely have to I'm supposed to set an example, I need to be the leader My crew looks for me to guide 'em If some shit ever just pop off I'm suppose to be beside 'em Now Ja said I tried to squash it, it was too late to stop it There's a certain line you just don't cross and he crossed it I heard him say Hailie's name on a song and I just lost it It was crazy, this shit be way beyond some Jay-Z and Nas shit And even though the battle was won, I feel like we lost it I spent too much energy on it, honestly I'm exhausted And I'm so caught in it I almost feel I'm the one who caused it This ain't what I'm in hip hop for, it's not why I got in it That was never my object for someone to get killed Why would I wanna destroy something I help build It wasn't my intentions, my intentions were good I went through my whole career without ever mentionin' [Suge] Now it's just out of respect, for not runnin' my mouth And talkin' about something that I knew nothing about Plus Dre told me stay out, this just wasn't my beef So I did, I just fell back, watched and gritted my teeth While he's all over TV, down talkin' a man who literally saved my life Like "fuck it I understand" this is business And this shit just isn't none of my business But still knowin' this shit could pop off at any minute 'cause..