China in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competitiveness Analysis of China's Main Coastal Ports

2019 International Conference on Economic Development and Management Science (EDMS 2019) Competitiveness analysis of China's main coastal ports Yu Zhua, * School of Economics and Management, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing 210000, China; [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: China coastal ports above a certain size, competitive power analysis, factor analysis, cluster analysis Abstract: As a big trading power, China's main mode of transportation of international trade goods is sea transportation. Ports play an important role in China's economic development. Therefore, improving the competitiveness of coastal ports is an urgent problem facing the society at present. This paper selects 12 relevant indexes to establish a relatively comprehensive evaluation index system, and uses factor analysis and cluster analysis to evaluate and rank the competitiveness of China's 30 major coastal ports. 1. Introduction Port is the gathering point and hub of water and land transportation, the distribution center of import and export of industrial and agricultural products and foreign trade products, and the important node of logistics. With the continuous innovation of transportation mode and the rapid development of science and technology, ports play an increasingly important role in driving the economy, with increasingly rich functions and more important status and role. Meanwhile, the competition among ports is also increasingly fierce. In recent years, with the rapid development of China's economy and the promotion of "the Belt and Road Initiative", China's coastal ports have also been greatly developed. China has more than 18,000 kilometers of coastline, with superior natural conditions. With the introduction of the policy of reformation and opening, the human conditions are also excellent. -

Nigeria Last Updated: May 6, 2016

Country Analysis Brief: Nigeria Last Updated: May 6, 2016 Overview Nigeria is currently the largest oil producer in Africa and was the world's fourth-largest exporter of LNG in 2015. Nigeria’s oil production is hampered by instability and supply disruptions, while its natural gas sector is restricted by the lack of infrastructure to commercialize natural gas that is currently flared (burned off). Nigeria is the largest oil producer in Africa, holds the largest natural gas reserves on the continent, and was the world’s fourth-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in 2015.1 Nigeria became a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1971, more than a decade after oil production began in the oil-rich Bayelsa State in the 1950s.2 Although Nigeria is the leading oil producer in Africa, production is affected by sporadic supply disruptions, which have resulted in unplanned outages of up to 500,000 barrels per day (b/d). Figure 1: Map of Nigeria Source: U.S. Department of State 1 Nigeria’s oil and natural gas industry is primarily located in the southern Niger Delta area, where it has been a source of conflict. Local groups seeking a share of the wealth often attack the oil infrastructure, forcing companies to declare force majeure on oil shipments (a legal clause that allows a party to not satisfy contractual agreements because of circumstances beyond their control). At the same time, oil theft leads to pipeline damage that is often severe, causing loss of production, pollution, and forcing companies to shut in production. -

Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce Belt and Road Countries Investment Index Report 2018 1 Foreword

Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce Belt and Road Countries Investment Index Report 2018 1 Foreword 2018 marked the fifth year since International Import Exposition Municipal Commission of Commerce, President Xi Jinping first put forward (CIIE), China has deepened its ties releasing the Belt and Road Country the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The with partners about the globe in Investment Index Report series Initiative has transformed from a trade and economic development. to provide a rigorous framework strategic vision into practical action President Xi Jinping has reiterated at for evaluating the attractiveness during these remarkable five years. these events that countries should of investing in each BRI country. enhance cooperation to jointly build Based on extensive data collection There have been an increasing a community of common destiny and in-depth analysis, we evaluated number of participating countries for all mankind , and the Belt and BRI countries' (including key and expanding global cooperation Road Initiative is critical to realizing African nations) macroeconomic under the BRI framework, along with this grand vision. It will take joint attractiveness and risks, and identified China's growing global influence. By efforts and mutual understanding to key industries with high growth the end of 2018, China had signed overcome the challenges ahead. potential, to help Chinese enterprises BRI cooperation agreements with better understand each jurisdiction's 122 countries and 29 international Chinese investors face risks in the investment environment. organizations. According to the Big BRI countries, most of which are Data Report of the Belt and Road developing nations with relatively The Belt and Road Country (2018) published by the National underdeveloped transportation and Investment Index Report 2017 Information Center, public opinion telecommunication infrastructures. -

Multimodal Transportation: the Case of Laptop from Chongqing in China to Rotterdam in Europe

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities Plymouth Business School 2017-09-30 Multimodal Transportation: The Case of Laptop from Chongqing in China to Rotterdam in Europe Seo, YJ http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/12698 10.1016/j.ajsl.2017.09.005 The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 33(3) (2017) 155-165 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics Journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ajsl Multimodal Transportation: The Case of Laptop from Chongqing in China to Rotterdam in Europe Young Joon SEOa, Feilong CHENb, Sae Yeon ROHc a Assistant Professor, Kyungpook National University, Korea, E-mail: [email protected] (First Author) b Master student, Plymouth university, United Kingdom, E-mail: [email protected] c Lecturer, Plymouth university, United Kingdom, E-mail: [email protected] (Corresponding Author) A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Multimodal transportation is a key component of modern logistics systems, especially for long- Received 23 June 2017 distance transnational transportation. This paper explores the various alternative routes for laptop Received in revised form 31 August 2017 Accepted 10 September 2017 exports from Chongqing, China to Rotterdam, the Netherlands. -

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

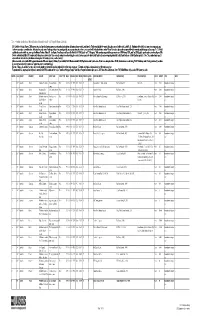

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Environmental Information from the Listed Companies (Main Board) In

Environmental The reports published annually to report the Hang Seng Stock Information company 's environmental performance No. Company Industry Code published on the Previous Classification 2019 2018 2017 website Report(s) 1 0043 C.P. Pokphand Company Ltd. 20 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Year 2016 2 0341 Café de Coral Holdings Ltd. 30 EI N/A SR SR and / or before Year 2016 Canvest Environmental Protection Group 3 1381 40 N/A N/A SR SR and / or Company Limited before Year 2016 4 0510 CASH Financial Services Group Ltd. 50 EI N/A AR AR and / or before Year 2016 5 0293 Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd. 30 EI AR SR SR and / or before Year 2016 Celestial Asia Securities Holdings Ltd. 6 1049 80 EI AR AR AR and / or (Net2Gather (China) Holdings Ltd.) before Year 2016 CGN New Energy Holdings Co., Ltd 7 1811 40 N/A N/A ER ER and / or (CGN Meiya Power Holdings Co., Ltd.) before Environmental The reports published annually to report the Hang Seng Stock Information company 's environmental performance No. Company Industry Code published on the Previous Classification 2019 2018 2017 website Report(s) CK Hutchison Holdings Limited N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A (Cheung Kong (Holdings) Ltd.) Citybase Property Management Ltd 8 0001 80 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A (member of Cheung Kong Property Group) Goodwell Property Management Ltd EI N/A N/A N/A N/A (member of Cheung Kong Property Group ) Year 2016 9 2778 Champion Real Estate Investment Trust 50 EI AR AR AR and / or before Year 2016 10 0092 Champion Technology Holdings Ltd. -

Comoros Mission Notes

Peacekeeping_4.qxd 1/14/07 2:29 PM Page 109 4.5 Comoros The 2006 elections in the Union of the support for a solution that preserves the coun- Comoros marked an important milestone in the try’s unity. After Anjouan separatists rejected peace process on the troubled archipelago. New an initial deal in 1999, the OAU, under South union president Ahmed Abdallah Mohamed African leadership, threatened sanctions and Sambi won 58 percent of the vote in elections, military action if the island continued to pur- described by the African Union as free and fair, sue secession. All parties eventually acceded and took over on 27 May 2006, in the islands’ to the 2001 Fomboni Accords, which provided first peaceful leadership transition since 1975. for a referendum on a new constitution in The AU Mission for Support to the Elections in advance of national elections. the Comoros (AMISEC), a short-term mission The core of the current deal is a federated devoted to the peaceful conduct of the elections, structure, giving each island substantial auton- withdrew from Comoros at the end of May, hav- omy and a turn at the presidency of the union, ing been declared a success by the AU and the which rotates every four years. Presidential Comorian government. The Comoros comprises three islands: Grande Comore (including the capital, Moroni), Anjouan, and Moheli. Following independ- ence from France in 1975, the country experi- enced some twenty coups in its first twenty- five years; meanwhile, Comoros slid ever deeper into poverty, and efforts at administra- tive centralization met with hostility, fueling calls for secession and/or a return to French rule in Anjouan and Moheli. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Hebdomadario De La Política Taiwanesa

HEBDOMADARIO DE LA POLÍTICA TAIWANESA Nº 13/2013 * Semana del 25 de Noviembre al 1 de Diciembre [email protected] 1) Informe 2) Observaciones de contexto 3) Datos relevantes 4) Nombres relevantes 1. Informe El anuncio de China continental del establecimiento de una Zona de Identificación de Defensa Aérea en el Mar de China Oriental, que incluye en su perímetro a las deshabitadas Diaoyutai, también provocó revuelo en Taiwán. Taipei, que calificó la decisión de “lamentable”, reunió a su Consejo de Seguridad Nacional y estableció contacto con EEUU y Japón, significando que ni sus reclamos de soberanía ni la leve superposición de esta nueva zona con la propia de la República de China motivarían cambios en la delimitación de su propia área. Por su parte, Beijing hizo saber que la citada zona concuerda “con los intereses de ambos lados del Estrecho”. A la pregunta de si Taiwán la aceptaría o no, el gobierno no ha respondido de manera definitiva pero 1 las aerolíneas han empezado a entregar sus planes de vuelo a China continental (al igual que Singapur o Filipinas y, unos días después, Corea del Sur y EEUU, por el momento) argumentando razones de seguridad. Taipei, señaló que la decisión, que en ningún caso fue objeto de consulta previa, no es favorable para el positivo desarrollo de las relaciones a través del Estrecho y así se lo hará saber al continente “a través de los canales adecuados”. La oposición acusó al gobierno de respuesta “muy débil” ante tal violación de la soberanía taiwanesa. Los diputados del PDP y la UST ocuparon el estrado de la presidencia del Yuan legislativo para protestar, exigiendo medidas enérgicas. -

Oryx Petroleum: Building an Upstream Leader in Africa & the Middle East

ORYX PETROLEUM: AN UPSTREAM LEADER IN AFRICA & THE MIDDLE EAST Investor Presentation - October 2013 BUILDING A FULL-CYCLE EXPLORATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRODUCTION COMPANY A sizeable and diverse portfolio focused on highly prospective oil regions ► Six license areas focused on Africa and Middle East ► Significant recent discovery with further upside • 164 MMbbls proved plus probable reserves ($0.8 billion AT NPV10) • 200 MMbbls contingent resources ($1.5 billion AT NPV10) ► First production targeted for Q2 2014 ► Large prospective oil resource base • 1,208 MMbbls unrisked (~$8.0 billion AT NPV10) ► Strong capitalisation: ~$1.0 billion of equity capital • $700 million from The Addax & Oryx Group (AOG) • $23 million from management and private investors • $237 million net proceeds from IPO ► ~$440 million cash on hand to fund active exploration, appraisal and first phase development program through mid-2014 ► TSX listed (ticker: OXC) Private and Confidential 2 PROVEN SENIOR MANAGEMENT TEAM Key management team members successfully established, developed and sold Addax Petroleum Jean Claude Gandur ► Former CEO and founder of Addax Addax Petroleum Chairman Petroleum ► Founder and Chairman of The ► 5th largest producer in Nigeria Addax & Oryx Group Ltd. ► Pioneer in Kurdistan Region of Iraq ► Recipient of honorary titles and awards from Benin, Nigeria, $60.00 Sale @ C$52.80 Senegal and Congo (Brazzaville) (Enterprise Value of C$10.2 billion) $50.00 Michael Ebsary ► Former CFO of Addax Petroleum Chief Executive Officer ► Elf and Occidental $40.00 $30.00 Henry Legarre ► Former M.D. Middle East Business Chief Operating Officer Unit of Addax Petroleum Equity raised @ C$27.25 (Pan-Ocean acquisition) ► Chevron (Angola, Nigeria and US) $20.00 IPO @ C$19.50 (Enterprise Value of C$2.4 billion) $10.00 Craig Kelly ► Former Head of Corporate Finance Addax created C$5.2 Billion in Shareholder Value Chief Financial Officer of Addax Petroleum (34% p.a. -

China in Latin America: the Storm on the Horizon Investigating Chinese Investment and Its Effects in Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia Christina Pendergrast

Prospectus Pendergrast 1 China in Latin America: The Storm on the Horizon Investigating Chinese Investment and its Effects in Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia Christina Pendergrast Over the past decade, China has steadily increased its economic presence throughout the global south.1 However, when it comes to scholarly analysis of Chinese investment policy, much of the scholarly focus has been placed on Africa despite major Chinese investments throughout Latin America. I plan to investigate the nature of Chinese investment in Latin America and how China plans to benefit from said investments. Therefore, this project seeks to discover: What kind of influence is China generating in Latin America through its economic investments, and how does/will that influence affect the balance of power in the region? This question interests me largely due to my experience within the realm of national security. While I was working with the State Department, I learned of the priority placed on China within the Intelligence Community. There were so many facets to the issue that it was hard to keep track of them all; however, I naturally gravitated towards the analysis of Chinese involvement in less developed countries. I had read about Chinese projects in Africa during my work with the Cipher Brief writing about developments in Africa, and to a lesser extent heard about China in the context of my Latin America regional classes. So, to research China in Latin America is a way that I can learn more about a topic relevant to the career I aspire to while contextualizing that new region within an area I am already familiar with.