The Effects and Management of Deciduous Trees on Waterways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Observations on the Biology and Host Plants of the Australian

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mauritiana Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 16_1996 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hawkeswood Trevor J., Turner James R., Wells Richard W. Artikel/Article: Further observations on the biology and host plants of the Australian longicorn beetle Agrianome spinicollis (Macleay) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) 327-332 ©Mauritianum, Naturkundliches Museum Altenburg Mauritiana (Altenburg) 16 (1997) 2, S. 327-332 Further observations on the biology and host plants of the Australian longicorn beetleAgrianome spinicollis (Macleay) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) With 1 Table and 1 Figure Trevor J. H awkeswood , James R. Turner and Richard W. Wells Abstract: New larval host plant records and further biological data are recorded for the large and distinctive Australian longicorn beetle,Agrianome spinicollis (Macleay) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). The presently known larval host plants are listed and original references cited. The adults are not known to feed and no data on adult hosts have ever been recorded. The suite of published larval host plants indicate that rainforest as well as woodland and sclerophyll forest communities are inhabited by this beetle. SinceAgrianome species are primitive cerambycids, it is suggested here that A.spinicollis originated (evolved first) in rainforest and as the Australian continental landmass dried out climatically, and sclerophylly evolved, the beetle adapted to plants belonging to these new plant communities. Zusammenfassung : Neufeststellungen von Wirtspflanzen der Larven und überdies biologische Daten für den großen, erhabenen australischen BockkäferAgrianome spinicollis (Macleay) (Coleoptera: Cerambyci dae) werden mitgeteilt. Alle gegenwärtig bekannten Wirtspflanzen der Larven werden unter Angabe der Literaturquellen aufgelistet. Von Wirtspflanzen der Imagines sind keinerlei Daten jemals registriert worden; auch ist nicht bekannt, daß adulte Käfer Nahrung brauchen. -

WRA Species Report

Family: Sterculiaceae Taxon: Brachychiton populneus Synonym: Poecilodermis populnea Schott & Endl. (basio Common Name: bottletree Sterculia diversifolia G. Don bottelboom kurrajong whiteflower kurrajong Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Chuck Chimera Designation: EVALUATE Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Chuck Chimera WRA Score 6 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 y 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 n 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable -

Brachychiton Populneus (Schott & Endl.) R

Brachychiton populneus (Schott & Endl.) R. Br., 1844 (Kurrajong) Identifiants : 4971/brapop Association du Potager de mes/nos Rêves (https://lepotager-demesreves.fr) Fiche réalisée par Patrick Le Ménahèze Dernière modification le 25/09/2021 Classification phylogénétique : Clade : Angiospermes ; Clade : Dicotylédones vraies ; Clade : Rosidées ; Clade : Malvidées ; Ordre : Malvales ; Famille : Malvaceae ; Classification/taxinomie traditionnelle : Règne : Plantae ; Sous-règne : Tracheobionta ; Division : Magnoliophyta ; Classe : Magnoliopsida ; Ordre : Malvales ; Famille : Malvaceae ; Sous-famille : Sterculioideae ; Genre : Brachychiton ; Synonymes : Poecilodermis populnea Schott & Endl. 1832 (=) basionym, Assonia populnea Cav. 1787 (synonyme selon DPC), Brachychiton diversifolium R.Br. (synonyme selon DPC), Dombeya populnea (Cav.) Baill. 1872 (nom accepté et espèce différente/distincte selon TPL), Sterculia caudata A Cunn. (synonyme selon DPC), Sterculia caudata Heward ex Benth. 1863 (synonyme selon DPC), Sterculia diversifolia G. Don 1831 (synonyme selon GRIN et DPC ; nom irrésolu selon TPL) ; Synonymes français : bois de senteur bleu, | sterculia à feuilles de peuplier{{{69 ; Nom(s) anglais, local(aux) et/ou international(aux) : bottletree (bottle tree), kurrajong, black kurrajong , bottelboom (af), kkoerajong (af), Kurrajong-Flaschenbaum (de), kurrajongträd (sv) ; Note comestibilité : *** Rapport de consommation et comestibilité/consommabilité inférée (partie(s) utilisable(s) et usage(s) alimentaire(s) correspondant(s)) : Fruit (graines0(+x),27(+x) [nourriture/aliment{{{(dp*), tronc (extrait(dp*) {gomme0(+x) et sève0(+x)}) et racine0(+x) comestibles0(+x). Détails : Graines consommées par les aborigènes{{{27(+x). Mise en garde. Les poils fins et irritants doivent être enlevés lors de la récolte. Les graines sont consommées crues ou grillées. Ils peuvent être moulus en farine et utilisés pour les amortisseurs ou les scones. Ils sont également transformés en une boisson de type café. -

Grey Box (Eucalyptus Microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia

Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia: A guide to the identification, assessment and management of a nationally threatened ecological community Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Glossary the Glossary at the back of this publication. © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercialised use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Public Affairs - Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2610 Australia or email [email protected] Disclaimer The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and is valid as at June 2012. The Australian Government is not liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. CONTENTS WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE? 1 NATIONALLY THREATENED ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITIES 2 What is a nationally threatened ecological community? 2 Why does the Australian Government list threatened ecological communities? 2 Why list the Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia as -

New Experimental Hosts and Further Information on Citrus Leprosis Virus

Fourteenth IOCV Conference, 2000—Other Viruses New Experimental Hosts and Further Information on Citrus Leprosis Virus O. Lovisolo, A. Colariccio, and V. Masenga ABSTRACT. Tetragonia tetragonioides (Tetragoniaceae), Atriplex hortensis, A. latifolia, Beta vulgaris ssp cicla and Chenopodium bonus-henricus (Chenopodiaceae) were found to be new experimental hosts of citrus leprosis virus (CiLV), extending its experimental host range outside the Rutaceae to 13 species belonging to 5 genera of the Centrospermae. All the herbaceous hosts react to mechanical inoculation only with local infection. Thirty three other species in 25 families, that have not been previously tested, were not susceptible to mechanical inoculation with CiLV. In vitro properties of CiLV in C. quinoa were further checked. The virus retained infectivity after 45 mo storage in dried-leaf and three days in infected sap at room temperature. Infectious CiLV was recovered in leaves of C. quinoa, 24 to 42 h after inoculation, or one to two days before symptom appearance. The typical particles and structures of CiLV have been seen in the thin sections obtained from local lesions of infected Chenopodium quinoa leaves. During 1997 and 1998 winter (from July to September) in São Paulo State no new leaf infections were found on sweet orange plants. Symptoms where present on old leaves of Cleopatra mandarin, but the virus content was very low, probably because of decrease of virus multiplication during the winter months. Knowledge on citrus leprosis buffer pH 7, containing 0.005 M Na- virus (CiLV) has advanced during Dieca, 0.001 M Na-EDTA, and 0.005 the last five years (5, 6, 10), but M Na-thioglycollate). -

Species List

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Brachychiton Rupestris (T

TAXON: Brachychiton rupestris (T. SCORE: 1.0 RATING: Evaluate Mitch. ex Lindl.) K. Schum. Taxon: Brachychiton rupestris (T. Mitch. ex Lindl.) K. Family: Malvaceae Schum. Common Name(s): bottletree Synonym(s): Delabechea rupestris T. Mitch. ex Lindl. narrow-leaf bottletree Queensland bottletree Queensland rattletree Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 3 Jan 2018 WRA Score: 1.0 Designation: EVALUATE Rating: Evaluate Keywords: Tropical Tree, Fodder, Ornamental, Drought-Tolerant, Slow Growing Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 n 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans y=1, n=0 n Creation Date: 3 Jan 2018 (Brachychiton rupestris (T. -

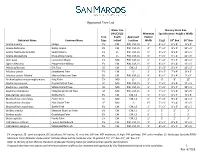

Approved Tree List

Approved Tree List Water Use Nursery Stock Size (WUCOLS) Minimum Specifications Height x Width Tree South Approved Planter Botanical Name Common Name Type Inland Location Width 15 gl. 24" Box 36" Box Acacia aneura Mulga EV LW PW, CM, LS 5' 4' x 3' 6' x 4' 8' x 5' Acacia baileyana Bailey Acacia EV LW PW, CM, LS 4' 7' x 2' 9' x 3' 12' x 4' Acacia fragesiana (smallii) Sweet Acacia EV VL PW, CM, LS 6' 6' x 3' 8' x 4' 10' x 5' Acacia stenophylla Shoe-string Acacia EV VL PW, CM, LS 5' 7' x 3' 9' x 4' 12' x 5' Acer paxii Evergreen Maple EV MD PW, CM, LS 5' 7' x 2' 9' x 3' 12' x 4' Agonis flexuosa Peppermint Willow EV LW PW, CM, LS 6' 6' x 3' 8' x 4' 12' x 5' Albizia julibrissin Silk Tree SE LW CM, LS 5' 6' x 3' 8' x 4' 10' x 5' Arbutus unedo Strawberry Tree EV LW LS 3' 6' x 3' 7' x 4' 8' x 5' Arbutus unedo 'Marina' Marina Madrone Tree EV LW PW, CM, LS 4' 6' x 3' 8' x 4' 9' x 5' Archontophoenix cunninghamiana King Palm EV MD LS 3' 6' 8' 12' Bauhinia purpurea Purple Orchid Tree SE MD PW, CM, LS 5' 7' x 3' 9' x 4' 12' x 5' Bauhinia v. candida White Orchid Tree SE MD PW, CM, LS 5' 7' x 3' 9' x 4' 10' x 5' Bauhinia x blakeana Hong Kong Orchid Tree SE MD PW, CM, LS 3' 7' x 3' 9' x 4' 10' x 5' Beaucarnea recurvata Bottle Palm EV LW CM, LS 5' 4' x 3' 6' x 4' 8' x 5' Brachychiton acerifolius Flame Tree SE MD CM, LS 6' 7' x 3' 9' x 4' 12' x 5' Brachychiton discolor Pink Flame Tree SE MD LS 15' 7' x 3' 9' x 4' 12' x 5' Brachychiton populneus Bottle Tree EV LW CM, LS 5' 7' x 2' 9' x 3' 10' x 5' Brahea armata Mexican Blue Fan Palm EV LW CM, LS 5' 1' 2' 3' -

Species List and Price

kentucky tree nursery www.kentuckytreenursery.com Chris & Maria Eveleigh Dandloo 24 Plug Street Eucalyptus acaciiformis Wattle-leaf peppermint Kentucky NSW 2354 Australia Eucalyptus aggregata Black gum ABN 94 479 550 455 Eucalyptus albens White box [email protected] Eucalyptus blakelyi Red gum Eucalyptus bridgesiana Apple box Eucalyptus caliginosa New England stringybark 67787342 Eucalyptus caleyi Caleyi's ironbark 0457787342 Eucalyptus camphora Broad leaf sally Eucalyptus camaldulensis River red gum Eucalyptus dalrympleana Mountain white gum native trees and shrubs Eucalyptus dorrigoensis Dorrigo white gum species list, price & order form Eucalyptus elliptica Bendemeer gum Eucalyptus laevopinea Silvertop stringybark Eucalyptus macrorhyncha Red stringybark Acacia amoena Boomerang wattle Eucalyptus melliodora Yellow box Acacia boormanii Snowy River wattle Eucalyptus michaeliana Hillgrove gum Acacia dealbata Silver wattle Eucalyptus moluccana Grey box Acacia filicifolia Fern leaf wattle Eucalyptus neglecta Omeo gum Acacia floribunda White sally wattle Eucalyptus nova anglica New England peppermint Acacia implexa Hickery wattle Eucalyptus pauciflora Snow gum Acacia melanoxylon Blackwood Eucalyptus perriniana Spinning gum Acacia rubida Red stemmed wattle Eucalyptus radiata Narrow leaved peppermint Acacia viscidula Sticky wattle Eucalyptus sideroxylon Mugga ironbark Eucalyptus stellulata Black sally Eucalyptus viminalis White gum Allocasuarina rigida Stiff she-oak Eucalyptus youmanii Youman's stringybark Angophora floribunda Rough-barked -

Brachychiton Populneus (Brp) Common Name: Kurrajong Tree

Design Standards for Urban Infrastructure Plant Species for Urban Landscape Projects in Canberra Botanical Name: Brachychiton populneus (BRp) Common Name: Kurrajong tree Species Description • Evergreen although some trees may be semi- deciduous in early summer • Medium sized tree with spreading crown • Hard grey bark with shallow fissures • Glossy green foliage, with juvenile foliage often being tri-lobed • Bell-shaped flowers from autumn to summer 10-12m • Large hard shelled seed pods Height and width 10 to 12 metres tall by 8 to 10 metres wide Species origin Indigenous to most areas of the eastern states of Australia, including the ACT Landscape use • Available Soil Volume required: ≥45m3 8-10m • Can be used as a street tree, but has shown variable performance • Can be used in parks, commercial precincts, revegetation areas • Suitable for use in home gardens Use considerations • Suited to all areas of the ACT but performs particularly well on higher ground in light soils • High frost tolerance once established and high drought tolerance • Grows well on most soils, including gravel, shale and sand, however performs better on higher ground on light soils • Long lived • Slow growth rate • Low flammability • Produces nectar and pollen which attract bees and birds • Excellent farm fodder, especially in drought prone areas Examples in Canberra Limestone Avenue; Furneaux Street, Griffith; Wickham Crescent, Red Hill; the Royal Canberra Golf Course and the Cotter Reserve Availability Commercially available or can be grown from local seed . -

Appendix B: Tree Species List

Appendix B: Tree Species List Small trees 3-8 metres in height Deciduous Name: Montpelier Maple (Acer monspessulanum ) Height: 6-8 metres Width: 5-8 metres Description: Small tree with oval to rounded form. The leaves can be variable, but typically three-blunt lobes, shiny dark green. Foliage is typically thick, leathery, turning yellow in autumn. The flowers are yellow-green and held in pendulous flower clusters. The flowers appear simultaneously with the new leaves. The fruit is a samara (winged seed) with many being sterile. Montpelier Maple is tolerant of dry conditions. It is intolerant of saline and sodic soils. It will grow in full sun to part shade. Name: Crimson Sentry Norway Maple (Acer platanoides ‘Crimson Sentry’) Height: 7-8 metres Width: 4-5 metres Description: Broadly columnar in form with a dense canopy of dark purple leaves with five sharp lobes. Leaves turn from purple to golden-brown autumn foliage. Moderate to high tolerance of dry conditions. Very tolerant of a wide array of soils. Adapts to extremes in soils; sand, clay, acid to alkaline. 55 Name: Sioux Crepe Myrtle ( Lagerstroemia indica x L. fauriei 'Sioux') Height: 4-5 metres Width: 3-4 metres Description: Small tree with upright vase form becoming rounded with age. Oval green foliage turning good autumn colour. Ornamental bark. Panicles of medium to hot pink flowers. Moderate to high tolerance of dry conditions once established. Adapts to a range of soils and transplants easily. Good small urban tree. Useful for narrow spaces. Low root impacts, low litter drop, no invasive potential. Name: Tuscarora Crepe Myrtle ( Lagerstroemia indica x L. -

Attachment 1 Tree Species Lists from Other Local Governments

Attachment 1 Tree species lists from other Local Governments City of Subiaco Botanical Name Common Name Agonis flexuosa WA weeping peppermint Angophora costata Smooth bark apple mytle Brachychiton acerifolius Illawara flame tree Brachychiton gregorii Desert Kurrajong Brachychiton populneus Delonix regia Ceratonia siliqua Carob tree Corymbia calophylla Marri Corymbia ficifolia Red flowering gum Erythrina indica Coral tree Eucalyptus decipiens Redheart Eucalyptus forrestiana Fuchsia gum Eucalyptus leucoxylon SA Red flowering gum Eucalyptus marginata Jarrah Eucalyptus melliodora Yellow box Eucalyptus nicholii Narrow leaved black peppermint Euclyptus rudis Flooded gum Gleditsia tricanthos 'Shademaster' Honey locust Hymenosporum flavum Native frangipani Jacaranda mimosifolia Jacaranda Magnolia grandifolia Southern magnolia Melaleuca quinquinervia Broad leaf paperbark Platanus acerifolia London plane Sapium sebiferum Chinese tallow Stenocarpus sinuatus Queensland firewhell Ulmus parvifolia Chinese elm City of Stirling Botanical Name Common Name Agonis flexuosa WA Peppermint Callistemon ‘Kings Park Special' Kings Park Special Bottlebrush Callistemon 'Dawson River' Weeping bottlebrush Corymbia eximia ‘nana’ Dwarf Golden Gum Corymbia ficifolia Red flowering gum Eucalyptus burdettiana Burdett’s Gum Eucalyptus decipiens Redheart Eucalyptus platypus var heterophylla Round leaved moort Fraxinus angustifolia ‘Raywood' Claret Ash Lophostemon confertus Brush Box Melaleuca quinquenervia Broad-leaved Paperbark Olea europaea European Olive Prunus cerecifera