The Windsor and Hampton Court Beauties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Dimensions

ONS NATIONAL DIM NATIONAL DIMENNATIONAL DIMENSIONS NAL DIMENSIONS DIMENSIONS NATIO This report was researched and written by AEA Consulting: Magnus von Wistinghausen Keith Morgan Katharine Housden This report sets out the collaborative work undertaken by the UK’s nationally funded museums, libraries and archives with other organisations across the UK, and assesses their impact on cultural provision across the nation. It focuses on the activities in recent years of members of the National Museum Directors’ Conference (NMDC), and is largely based on discussions with these institutions and selected partner organisations, as well as on a series of discussion days hosted by the NMDC in different regional centres in July 2003. It does not make specific reference to collaborative work between NMDC organisations themselves, and focuses on activities and initiatives that have taken place in the last few years. For the sake of simplicity the term ‘national museum’ is used throughout the report to describe all NMDC member organisations, notwithstanding the fact that these also include libraries and archives. In this report the term ‘national’ is used to denote institutions established by Act of Parliament as custodians of public collections that belong to the nation. It is acknowledged that the NMDC does not include all museums and other collecting institutions which carry the term ‘national’ as part of their name. Specific reference to their activities is not contained in this report. Published in the United Kingdom by the National Museum Directors' -

British Pa Inters Their Story and Their

H rTP S BRIT ISH PA INT ERS T H EIR ST O RY A ND T H EIR A RT J E . DGC UMBE ST A LEY A UT H OR OF WA TT EA U A ND H I S SCH OOL ET C . WIT H TWENTY -FO UR EXAMPLES IN C OLOUR O F T H EIR WO RK P RE FA C E “ BRI TI SH P A I NT E RS : Their Story and their Art l o f o f is a presentation, in popu ar form , the Story — - British Painting a well worn but never wearying t o Story , which for ever offers fresh charms young o ld and , and stirs in British hearts feelings of patriotism and delight . In a work o f the size of this volume it is im possible to d o more than lightly sketch the more sa lient features o f the glorious panorama o f seven hundred years . My purpose , in this compilation , —t o is threefold . First bring into stronger light the painting glories o f the earlier artists o f Britain many people are unfamiliar with the lives and s o f work of the precur ors Hogarth . Secondly to t reat especially o f the persons and art of painte rs Whose works are exhibited in o u r Public Galleries pictures in private holding are often inaccessible t o o f and the generality people, besides, they — co nstantly changing locality this is true of T — the Royal Collections . hirdl y t o vindicate the a of t o cl im Britain be regarded as an ancient , vii BRIT I S H P A I NT E RS consistent , and renowned Home of the Fine Arts and to correct the strange insular habit o f self depreciation, by showing that the British are supreme as a tasteful and artistic people . -

Thecourtauldregister of Interestsgb 2019

THE COURTAULD INSTITUTE OF ART REGISTER OF RELEVANT INTERESTS – February 2019 The CUC code of practice advises that ‘The institution shall maintain and publicly disclose a register of interests of members of the governing body’. The declared interests of the members of The Board of Directors of The Courtauld Institute of Art are as follows INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS Chairman Lord Browne of Madingley, Edmund John Phillip Browne Executive Chairman, L1 Energy (UK) LLP Interest (organisation name) Registration details (iF Capacity Start date disclosed) Francis Crick Institute Chairman August 2017 Pattern Energy Group Director October 2013 Huawei Technologies (UK) Co Limited Chairman February 2015 L1 Energy (UK) LLP Executive Chairman March 2015 DEA Deutsche Erdoel AG Chairman of the Supervisory Board March 2015 Accenture Global Energy Board Chairman April 2010 Stanhope Capital Advisory Board Chairman July 2010 L1 Energy Advisory Board Chairman June 2013 NEOS GeoSolutions Adviser December 2015 Angeleno Group Member of the Board of Advisors August 2016 Velo Restaurants Ltd Shareholder NA SATMAP Inc doing business as Afiniti Advisory board (and shareholder) April 2016 Gay Star News Shareholder NA Kayrros SAS Shareholder NA Windward Maritime Limited Shareholder NA Pattern Energy Group Inc Shareholder NA IHS Markit Director and Shareholder NA UKTI Business Ambassador Honorary – not current Edelman Ltd Member of the Advisory Board September 2016 Board of Donmar Warehouse Chair December 2014 American Friends of Donmar Theatre Inc Director March 2015 International -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

Dining Room 14

Dining Room 14 Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset Richard Lumley, 2nd Earl of (1643–1706) Scarborough (1688?–1740) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) Oil on canvas, c.1697 Oil on canvas, 1717 NPG 3204 NPG 3222 15 16 Thomas Hopkins (d.1720) John Tidcomb (1642–1713) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) Oil on canvas, 1715 Oil on canvas, c.1705–10 NPG 3212 NPG 3229 Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle Richmond and Lennox (1672–1723) (1669 –1738) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646 –1723) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646 –1723) Oil on canvas, c.1703–10 Oil on canvas, c.1700–12 NPG 3221 NPG 3197 John Dormer (1669–1719) Abraham Stanyan (c.1669–1732) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646 –1723) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) Oil on canvas, c.1705–10 Oil on canvas, c.1710–11 NPG 3203 NPG 3226 Charles Mohun, 4th Baron Mohun Algernon Capel, 2nd Earl of Essex (1675?–1712) (1670–1710) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646 –1723) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) Oil on canvas, 1707 Oil on canvas, 1705 NPG 3218 NPG 3207 17 15 Further Information If there are other things that interest you, please ask the Room Steward. More information on the portraits can be found on the Portrait Explorer upstairs. All content © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG) or The National Trust (NT) as indicated. Dining Room 14 William Walsh (1662–1708) Charles Dartiquenave by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) (1664?–1737) Oil on canvas, c.1708 after Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) NPG 3232 Oil on -

Darnley Portraits

DARNLEY FINE ART DARNLEY FINE ART PresentingPresenting anan Exhibition of of Portraits for Sale Portraits for Sale EXHIBITING A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS FOR SALE DATING FROM THE MID 16TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY On view for sale at 18 Milner Street CHELSEA, London, SW3 2PU tel: +44 (0) 1932 976206 www.darnleyfineart.com 3 4 CONTENTS Artist Title English School, (Mid 16th C.) Captain John Hyfield English School (Late 16th C.) A Merchant English School, (Early 17th C.) A Melancholic Gentleman English School, (Early 17th C.) A Lady Wearing a Garland of Roses Continental School, (Early 17th C.) A Gentleman with a Crossbow Winder Flemish School, (Early 17th C.) A Boy in a Black Tunic Gilbert Jackson A Girl Cornelius Johnson A Gentleman in a Slashed Black Doublet English School, (Mid 17th C.) A Naval Officer Mary Beale A Gentleman Circle of Mary Beale, Late 17th C.) A Gentleman Continental School, (Early 19th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Gerard van Honthorst, (Mid 17th C.) A Gentleman in Armour Circle of Pieter Harmensz Verelst, (Late 17th C.) A Young Man Hendrick van Somer St. Jerome Jacob Huysmans A Lady by a Fountain After Sir Peter Paul Rubens, (Late 17th C.) Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel After Sir Peter Lely, (Late 17th C.) The Duke and Duchess of York After Hans Holbein the Younger, (Early 17th to Mid 18th C.) William Warham Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller, (Early 18th C.) Head of a Gentleman English School, (Mid 18th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Hycinthe Rigaud, (Early 18th C.) A Gentleman in a Fur Hat Arthur Pond A Gentleman in a Blue Coat -

Microscopy and Archival Research: Interpreting Results Within the Context of Historical Records and Traditional Practice

Microscopy and archival research: interpreting results within the context of historical records and traditional practice Jane Davies 32 ISSUE 3 SEPT 2006 The analysis of paint samples is an invaluable tool in the armoury of historic paint research. However, powerful as the techniques of pigment, cross-sectional and instrumental analysis may be, they cannot always provide complete answers to the questions posed. Historical records relating to specific buildings and projects, as well as painters’ manuals recording traditional painting techniques can offer clues which are vital to solving analysis puzzles. Historical text records which are particular to buildings and/or paintings can provide definitive dates for paint schemes which could otherwise only be dated approximately if key ‘marker’ pigments with known dates of introduction or obsolescence are present. Reference sources may be useful in suggesting or guiding proposed research and conversely, sample analysis can lead to a reassessment of archive records and a refinement of their interpretation. The application of cross-sectional analysis to the or redecoration decisions. To fulfil this role, I look investigation of architectural paint was pioneered in to a broad range of clues, drawing from diverse the 1970s by Ian Bristow and Josephine Darrah. sources, such as standing structure archaeology and During my research degree I was fortunate enough archival research — using all pieces of evidence to study microscopy with Jo Darrah at the Victoria available. Paper based archives such as accounts, and Albert Museum.This training, together with my correspondence and diaries, and artists images, tend painting conservator’s understanding of artist’s to be site specific. -

Wren and the English Baroque

What is English Baroque? • An architectural style promoted by Christopher Wren (1632-1723) that developed between the Great Fire (1666) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). It is associated with the new freedom of the Restoration following the Cromwell’s puritan restrictions and the Great Fire of London provided a blank canvas for architects. In France the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 revived religious conflict and caused many French Huguenot craftsmen to move to England. • In total Wren built 52 churches in London of which his most famous is St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711). Wren met Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in Paris in August 1665 and Wren’s later designs tempered the exuberant articulation of Bernini’s and Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture in Italy with the sober, strict classical architecture of Inigo Jones. • The first truly Baroque English country house was Chatsworth, started in 1687 and designed by William Talman. • The culmination of English Baroque came with Sir John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) and Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), Castle Howard (1699, flamboyant assemble of restless masses), Blenheim Palace (1705, vast belvederes of massed stone with curious finials), and Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight (now in ruins). Vanburgh’s final work was Seaton Delaval Hall (1718, unique in its structural audacity). Vanburgh was a Restoration playwright and the English Baroque is a theatrical creation. In the early 18th century the English Baroque went out of fashion. It was associated with Toryism, the Continent and Popery by the dominant Protestant Whig aristocracy. The Whig Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham, built a Baroque house in the 1720s but criticism resulted in the huge new Palladian building, Wentworth Woodhouse, we see today. -

Lord Henry Howard, Later 6Th Duke of Norfolk (1628 – 1684)

THE WEISS GALLERY www.weissgallery.com 59 JERMYN STREET [email protected] LONDON, SW1Y 6LX +44(0)207 409 0035 John Michael Wright (1617 – 1694) Lord Henry Howard, later 6th Duke of Norfolk (1628 – 1684) Oil on canvas: 52 ¾ × 41 ½ in. (133.9 × 105.4 cm.) Painted c.1660 Provenance By descent to Reginald J. Richard Arundel (1931 – 2016), 10th Baron Talbot of Malahide, Wardour Castle; by whom sold, Christie’s London, 8 June 1995, lot 2; with The Weiss Gallery, 1995; Private collection, USA, until 2019. Literature E. Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 – 1790, London 1953, p.72, plate 66b. G. Wilson, ‘Greenwich Armour in the Portraits of John Michael Wright’, The Connoisseur, Feb. 1975, pp.111–114 (illus.). D. Howarth, ‘Questing and Flexible. John Michael Wright: The King’s Painter.’ Country Life, 9 September 1982, p.773 (illus.4). The Weiss Gallery, Tudor and Stuart Portraits 1530 – 1660, 1995, no.25. Exhibited Edinburgh, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, John Michael Wright – The King’s Painter, 16 July – 19 September 1982, exh. cat. pp.42 & 70, no.15 (illus.). This portrait by Wright is such a compelling amalgam of forceful assurance and sympathetic sensitivity, that is easy to see why that doyen of British art historians, Sir Ellis Waterhouse, described it in these terms: ‘The pattern is original and the whole conception of the portrait has a quality of nobility to which Lely never attained.’1 Painted around 1660, it is the prime original of which several other studio replicas are recorded,2 and it is one of a number of portraits of sitters in similar ceremonial 1 Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 to 1790, 4th integrated edition, 1978, p.108. -

Press Release CORPUS: the Body Unbound Courtauld Gallery 16 June

Press Release CORPUS: The Body Unbound Courtauld Gallery 16 June – 16 July 2017 Wolfgang Tillmans, Dan, 2008. C-Type print, 40 x 30 cm Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © Wolfgang Tillmans, courtesy Maureen Paley, London ● An exhibition curated by MA Curating the Art Museum students at The Courtauld Institute of Art ● Featuring major artworks from The Courtauld Collection and the Arts Council Collection ● CORPUS: The Body Unbound explores how artists past and present have engaged with the body to interrogate, analyse and reimagine fundamental aspects of the human condition ● Curated in response to The Courtauld Gallery’s Special Display Bloomsbury: Art & Design CORPUS: The Body Unbound explores how artists past and present have engaged with the body - the corpus - to interrogate, analyse and reimagine fundamental aspects of the human condition. For artists, the human figure has been a site of optimism, a source of anxiety, as well as a symbol of limitations imposed by the self and society. Curated by the students of the Courtauld’s MA Curating the Art Museum, CORPUS: The Body Unbound responds to The Courtauld Gallery’s Special Display Bloomsbury Art & Design, on view in the adjacent gallery. Spanning more than 600 years of artistic practice, this exhibition brings together works from The Courtauld Gallery and the Arts Council Collection, creating unexpected confrontations and dialogues across time, space and media. Works by artists including Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Henry Moore (1898-1986) and Wolfgang Tillmans (b.1968) explore the strength and fragility of the body and the potential optimism of the human spirit in times of conflict. -

Sarah Churchill by Sir Godfrey Kneller Sarah Churchill Sarah Churchill Playing Cards with Lady Fitzharding Barbara Villiers by S

05/08/2019 Sarah Churchill by Sir Godfrey Kneller Sarah Churchill Sarah Churchill playing cards with Sarah Churchill by Sir Godfrey Lady Fitzharding Barbara Villiers by Kneller Sir Godfrey Kneller Letter from Mrs Morley to Mrs Freeman Letter from Mrs Morley to Mrs Freeman 1 05/08/2019 Marlborough ice pails possibly by Daivd Willaume, British Museum The end of Sarah on a playing card as Anne gives the duchess of Somerset John Churchill 1st Duke of Sarah's positions Marlborough by John Closterman after John Riley John Churchill by Sir Godfrey Kneller John Churchill by Sir Godfrey Kneller 2 05/08/2019 John Churchill by the studio of John John Churchill Michael Rysbrack, c. 1730, National Portrait Gallery John Churchill in garter robes John Churchill by Adriaen van der Werff John with Colonel Armstrong by Seeman Marlborough studying plans for seige of Bouchain with engineer Col Armstrong by Seeman 3 05/08/2019 Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud Nocret’s Family Portrait of Louis in Classical costumes 1670 Charles II of Spain artist unknown Louis XIV and family by Nicholas de Largillière Philip V of Spain by Hyacinthe Rigaud Charles of Austria by Johann Kupezky 4 05/08/2019 James Fitzjames D of Berwick by Eugene of Savoy by Sir Godfrey unknown artist Kneller Blenheim tapestry Marshall Tallard surrendering to Churchill by Louis Laguerre Churchill signing despatches after Blenheim by Robert Alexander Hillingford 5 05/08/2019 Note to Sarah on the back of a tavern bill Sir John Vanbrugh by Sir Godfrey Kneller Castle Howard Playing card showing triumph in London Blenheim Palace 6 05/08/2019 Admiral Byng by Jeremiah Davison Ship Model Maritime Museum 54 guns Louis swooning after Ramillies Cartoon of 1706 Pursuit of French after Ramillies by Louis Laguerre 7 05/08/2019 Thanksgiving service after Ramillies Oudenarde by John Wootton Oudenarde on a playing card Malplaquet by Louis Laguerre Malplaquet tapestry at Marlbrook s'en va t'en guerre Blenheim 8 05/08/2019 Marlborough House Marlborough House Secret Peace negotiations 1712 Treaty of Utrecht 1713 9. -

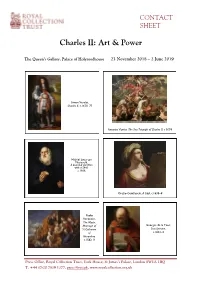

Charles II: Art & Power

CONTACT SHEET Charles II: Art & Power The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 23 November 2018 – 2 June 2019 Simon Verelst, Charles II, c.1670–75 Antonio Verrio, The Sea Triumph of Charles II, c.1674 Michiel Jansz van Miereveld, A bearded old Man with a Shell, c.1606 Orazio Gentileschi, A Sibyl, c.1635–8 Paolo Veronese, The Mystic Marriage of Georges de la Tour, St Catherine Saint Jerome, of c.1621–3 Alexandria, c.1562–9 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Parmigianino, Head of Pallas Athena, Holofernes, c.1531–8 1613 Sir Peter Lely, Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Catherine of Duchess of Braganza, Cleveland, c.1663–65 c.1665 Pierre Fourdrinier, The Royal Palace of Holyrood House, Side table, c.1670 c.1753 Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the Hans Holbein the back and arm, Younger, Frances, c. 1508 Countess of Surrey, c.1532–3 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk A selection of images is available at www.picselect.com. For further information contact Royal Collection Trust Press Office +44 (0)20 7839 1377 or [email protected]. Notes to Editors Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen.