Jake Hinkson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May Be Used for Personal Purporses Only Or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 Associated to Dandelon.Com Network

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 associated to dandelon.com network. Mit Beiträgen von Frieda Grafe Enno Patalas Hans Helmut Prinzler Peter Syr (Fotos) Carl Hanser Verlag Inhalt Für Fritz Lang Einen Platz, kein Denkmal Von Frieda Grafe 7 Kommentierte Filmografie Von Enno Patalas 83 Halbblut 83 Der Herr der Liebe 83 Der goldene See. (Die Spinnen, Teil 1) 83 Harakiri 84 Das Brillantenschiff. (Die Spinnen, Teil 2) 84 Das wandernde Bild 86 Kämpfende Herzen (Die Vier um die Frau) 86 Der müde Tod 87 Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler 88 Die Nibelungen 91 Metropolis 94 Spione 96 Frau im Mond 98 M 100 Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse 102 Liliom 104 Fury 105 You Only Live Once. Gehetzt 106 You and Me [Du und ich] 108 The Return of Frank James. Rache für Jesse James 110 Western Union. Überfall der Ogalalla 111 Man Hunt. Menschenjagd 112 Hangmen Also Die. Auch Henker sterben 113 Ministry of Fear. Ministerium der Angst 115 The Woman in the Window. Gefährliche Begegnung 117 Scarlet Street. Straße der Versuchung 118 Cloak and Dagger. Im Geheimdienst 120 Secret Beyond the Door. Geheimnis hinter der Tür 121 House by the River [Haus am Fluß] 123 American Guerrilla in the Philippines. Der Held von Mindanao 124 Rancho Notorious. Engel der Gejagten 125 Clash by Night. Vor dem neuen Tag 126 The Blue Gardenia. Gardenia - Eine Frau will vergessen 128 The Big Heat. Heißes Eisen 130 Human Desire. Lebensgier 133 Moonfleet. Das Schloß im Schatten 134 While the City Sleeps. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

UCLA FESTIVAL of PRESERVATION MARCH 3 to MARCH 27, 2011

UCLA FESTIVAL of PRESERVATION MARCH 3 to MARCH 27, 2011 i UCLA FESTIVAL of PRESERVATION MARCH 3 to MARCH 27, 2011 FESTIVAL SPONSOR Additional programming support provided, in part, by The Hollywood Foreign Press Association ii 1 FROM THE DIRECTOR As director of UCLA Film & Television Archive, it is my great pleasure to Mysel has completed several projects, including Cry Danger (1951), a introduce the 2011 UCLA Festival of Preservation. As in past years, we have recently rediscovered little gem of a noir, starring Dick Powell as an unjustly worked to put together a program that reflects the broad and deep efforts convicted ex-con trying to clear his name, opposite femme fatale Rhonda of UCLA Film & Television Archive to preserve and restore our national mov- Fleming, and featuring some great Bunker Hill locations long lost to the Los ing image heritage. Angeles wrecking ball. An even darker film noir, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950), stars James Cagney as a violent gangster (in fact, his last great This year’s UCLA Festival of Preservation again presents a wonderful cross- gangster role) whose id is more monstrous than almost anything since Little section of American film history and genres, silent masterpieces, fictional Caesar. Add crooked cops and a world in which no one can be trusted, and shorts, full-length documentaries and television works. Our Festival opens you have a perfect film noir tale. with Robert Altman’s Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982). This restoration is the first fruit of a new project to preserve Our newsreel preservationist, Jeff Bickel, presents his restoration of John and restore the artistic legacy of Mr. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

REJECTED WOMEN IN FILM NOIR By CAROLYN A. KELLEY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Carolyn A. Kelley 2 To my mother and father, Elaine and Thomas Kelley 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank my parents, Thomas and Elaine Kelley, for their unwavering love and support. You are the kindest, most generous people I know. I am proud to be your daughter. To my sister, Christine Kelley-Connors, thank you for always making me laugh and for helping me keep my perspective. I thank my ―second parents,‖ Madeline and Stuart Sheets, for always listening to me and for giving me excellent advice. I thank Ted Kingsbury for introducing me to classic Hollywood films through his Thursday night screenings at the Wellesley library. To Professors Patrick Murphy, Edward O‘Shea, Jean Chambers, and Steven Abraham of Oswego State University, and Julian Wolfreys of Loughborough University, I thank you for your support, friendship, advice and generosity in sharing your knowledge. Thanks also go out to Professors Pamela Gilbert, Kenneth Kidd, and Chris Snodgrass of the University of Florida for your thoughtful guidance, wisdom and patience. To my dissertation committee members, Robert Ray, Marsha Bryant, and Louise Newman, I appreciate your generous devotion to helping me shape this project and your helpful, insightful input. And, to my Dissertation Director, Maureen Turim, I thank you for your guidance, patience, intelligence, and kindness. Finally, to everyone listed on this page, please know this project would not have been possible without you, and I am extremely grateful to you all. -

Lang, Fritz , 1890–1976, German-American Film Director, B

Lang, Fritz , 1890–1976, German-American film director, b. Vienna. His silent and early sound films, such as Metropolis (1926), are marked by brilliant expressionist technique. He gained worldwide acclaim with M (1933), a study of a child molester and murderer. After directing 15 films, Lang fled Nazi Germany (1933) to avoid collaborating with the government and settled in the United States. His 20 Hollywood films continued his exploration of criminality and the cruel fate that can overtake the unwary. His notable American works include Fury (1936), You Only Live Once (1937), Hangmen Also Die (1943), The Big Heat (1953), and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956). Born in Vienna, Austria, Fritz Lang’s father managed a construction company. His mother, Pauline Schlesinger, was Jewish but converted to Catholicism when Lang was ten . After high school he enrolled briefly at the Technische Hochschule Wien, then started to train as a painter. From 1910 to 1914 he traveled in Europe and, he would later claim, also in Asia and North Africa. He studied painting in Paris in 1913-14. At the start of the First World War he returned to Vienna, enlisting in the army in January 1915. Severely injured in June 1916, he wrote some scenarios for films while convalescing. In early 1918 he was sent home shell-shocked and acted briefly in Viennese theater before accepting a job as a writer at Erich Pommer's production company in Berlin, Decla. In Berlin, Lang worked briefly as a writer and then as a director, at UFA and then for Nero-Film, owned by the American Seymour Nebenzahl. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Amzejor 1910 Agnew Says U.S. Stands By

amzeJor 1910 SEE STORIES INSIDE Fair and Cold THEDAILY FINAL Partly sunny and cold today. Clear, cold tonight. Cloudy, Red Bank, Freehold inow possible tomorrow. I „ Long Brandt 7 EDITION (Set CeUlU, Fill 31 Monmouth County's Home Newspaper tor 92 Years VOL. 93, NO. 131 RED BANK, N, J., FRIDAY, JANUARY 2, 1970 10 CENTS Agnew Says U.S. Stands By TAIPEI (AP) — Vice mainland China reflect a with the Communist Chin&se among Asian nations will cularly upset by the recent President Spiro T. Agnew ar- hope they will lead to steps do not in any way affect Hie mean a tapering off of diplo- relaxation of U.S. trade em- rived in Formosa today to by the Chinese Communists U.S. commitment to the Na- matic and military support bargoes against Communist assure Nationalist China the to lessen Uie tensions that ex» tionalist Chinese. for President Chiang Kai- China. The charge in trade U.S. government intends to ist in Asia. shek's regime. policy is regarded as a stand by it? treaty commit- The .United States, lie con- The Nationalist Chinese Recent reports that the. breach in U.S. diplomatic ments. But en route from tinued, should not sit still in ^capital was the third Asian United States is planning a support which, among other Vietnam he said the Nixon a stance of armed prepared- capital on Uie vice presi- reduction in« naval patrols, in things, has..:enabled the Na- administration favors initia- ness and make no initiatives dent's tour. Awaiting him the Formosa Strait, one of tionalists to keep China's seat tives to lesson tensions with to develop an atmosphere during his overnight stay was Nationalist China's major in the United Nations. -

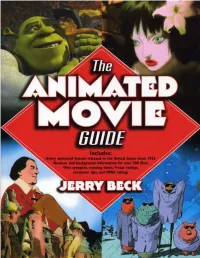

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H.