University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Las Alas De Ícaro: El Trailer Cinematogáfico, Un Tejido Artístico De Sueños

Las Alas de Ícaro: El un tejido artístico de sueños. Las Alas de Ícaro: El trailer cinematogáfico, un tejido artístico de sueños. Tesis doctoral presentada por María Lois Campos, bajo la dirección del doctor D. José Chavete Rodríguez. Facultad de Bellas Artes, Departamento de Pintura de la Universidad de Vigo. Pontevedra 2014 / 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS Quiero expresar mis más sincero agradecimiento a todas aquellas personas que me han apoyado y motivado a lo largo de mis estudios. Voy a expresar de un modo especial mis agradecimientos: • En particular agradezco al Profesor José Chavete Rodríguez la confianza que ha depositado en mí para la realización de esta investigación; por su apoyo, trato esquisito, motivación constante y sabios consejos a lo largo de dicho proceso. • En especial agradezco a Joaquina Ramilo Rouco (Documentalista- Information Manager) su paciencia a la hora de intentar resolver mis dudas. • También expreso mi reconocimiento al servicio de Préstamo Interbibliotecario (Tita y Asunción) y al servicio de Referencia de la Universidad de Vigo, así como a Héctor, Morquecho, Fernando, Begoña (Biblioteca de Ciencias Sociales de Pontevedra) y al personal de la Biblioteca de Torrecedeira en Vigo. • Quisiera hacer extensiva mi gratitud al profesor Suso Novás Andrade y a Ana Celia (Biblioteca de Bellas Artes) por el tiempo invertido a la hora de solventar mis dudas a lo largo del proceso de investigación. • Debo asimismo, mostrar un agradecimiento ante el hecho de haber sido alumna de Juan Luís Moraza Pérez, Consuelo Matesanz Pérez, Manuel Sendón Trillo, Fernando Estarque Casás, Alberto Ruíz de Samaniego y Rosa Elvira Caamaño Fernández, entre otros profesores, por haber aportado sus conocimientos, así como mostrarme otros universos en torno al arte. -

Savage Winter #Bamnextwave No Intermission LOCATION: RUN TIME: DATES: Pittsburgh Opera Approx 1Hr15mins BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) NOV 7—10At7:30Pm

Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Savage Winter Executive Producer American Opera Projects and Pittsburgh Opera Music by Douglas J. Cuomo Directed by Jonathan Moore DATES: NOV 7—10 at 7:30pm Season Sponsor: LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) Leadership support for music programs at BAM RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 15mins provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund. no intermission #BAMNextWave BAM Fisher Savage Winter Written and Composed by Music Director This project is supported in part by an Douglas J. Cuomo Alan Johnson award from the National Endowment for the Arts, and funding from The Andrew Text based on the poem Winterreise by Production Manager W. Mellon Foundation. Significant project Wilhelm Müller Robert Signom III support was provided by the following: Ms. Michele Fabrizi, Dr. Freddie and Directed by Production Coordinator Hilda Fu, The James E. and Sharon C. Jonathan Moore Scott H. Schneider Rohr Foundation, Steve & Gail Mosites, David & Gabriela Porges, Fund for New Performers Technical Director and Innovative Programming and The Protagonist: Tony Boutté (tenor) Sean E. West Productions, Dr. Lisa Cibik and Bernie Guitar/Electronics: Douglas J. Cuomo Kobosky, Michele & Pat Atkins, James Conductor/Piano: Alan Johnson Stage Manager & Judith Matheny, Diana Reid & Marc Trumpet: Sir Frank London Melissa Robilotta Chazaud, Francois Bitz, Mr. & Mrs. John E. Traina, Mr. & Mrs. Demetrios Patrinos, Scenery and properties design Assistant Director Heinz Endowments, R.K. Mellon Brandon McNeel Liz Power Foundation, Mr. & Mrs. William F. Benter, Amy & David Michaliszyn, The Estate of Video design Assistant Stage Manager Jane E. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Metropolis, 1927, Director: Fritz Lang

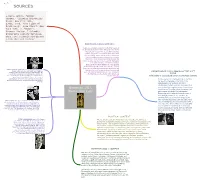

SOURCES 1.Kaes, Anton, *Weimar Cinema,* Columbia University Press: New York 2009. 2.Ott, Fred, *The Films of Fritz Lang*, Lyle Stuart: New York 1979. 3. "Women's Pioneer Project," Columbia University Library Services, wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pionee r/ccp-thea-von-harbou/ SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT Inspired, according to Lang, by his first impression of the Manhattan skyline in 1924, Metropolis was written in 1924 and released nine years after Germany's defeat in World War I, and like all great sci-fi films, reflects both the hopes and the fears of a turbulent society heading towards modernization. In part a meditation on the future relationship between the human and the machine in this modernity. Metropolis is "a great cinematic document of German Expressionism" which "fulfilled the expressionist Weltanschauung that a work of art should [...] finally propound the belief that through the destruction and BRIGITTE HELM, 1906-1996, star of Metropolis (along with rebirth of the world, a new and pure humanity will Gustav Frolich as Feder and Rudolf Klein Rogge as CINEMATOGRAPHY IN CHANGING OF THE SHIFT Rotwang, who also played Caligari in The Cabinet of Dr. arise: the dawn of the Kingdom of Love," while also Caligari and Dr. Mabuse in Dr. Mabuse the Gambler and reflecting that era's fascination with cubism and SCENE The Testament of Dr. Mabuse) in which she played both the futurism (Ott 124). (relationship of sociocultural context to cinematic element) good-hearted working girl Maria and her evil robot doppleganger. One of the most startling and memorable In this scene from the beginning of the film, scenes in the movie is her mesmerizing, lascivious dance in a brothel. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

2005 Next Wave Festival

November 2005 2005 Next Wave Festival Mary Heilmann, Last Chance for Gas Study (detail), 2005 BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by: The PerformingNCOREArts Magazine Altria 2005 ~ext Wave FeslliLaL Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman William I. Campbell Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents Symphony No.6 (Plutonian Ode) & Symphony No.8 by Philip Glass Bruckner Orchestra Linz Approximate BAM Howard Gilman Opera House running time: Nov 2,4 & 5, 2005 at 7:30pm 1 hour, 40 minutes, one intermission Conducted by Dennis Russell Davies Soprano Lauren Flanigan Symphony No.8 - World Premiere I II III -intermission- Symphony No. 6 (Plutonian Ode) I II III BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc. Major support for Symphonies 6 & 8 is provided by The Robert W Wilson Foundation, with additional support from the Austrian Cultural Forum New York. Support for BAM Music is provided by The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc. Yamaha is the official piano for BAM. Dennis Russell Davies, Thomas Koslowski Horns Executive Director conductor Gerda Fritzsche Robert Schnepps Dr. Thomas Konigstorfer Aniko Biro Peter KeserU First Violins Severi n Endelweber Thomas Fischer Artistic Director Dr. Heribert Schroder Heinz Haunold, Karlheinz Ertl Concertmaster Cellos Walter Pauzenberger General Secretary Mario Seriakov, Elisabeth Bauer Christian Pottinger Mag. Catharina JUrs Concertmaster Bernhard Walchshofer Erha rd Zehetner Piotr Glad ki Stefa n Tittgen Florian Madleitner Secretary Claudia Federspieler Mitsuaki Vorraber Leopold Ramerstorfer Elisabeth Winkler Vlasta Rappl Susanne Lissy Miklos Nagy Bernadett Valik Trumpets Stage Crew Peter Beer Malva Hatibi Ernst Leitner Herbert Hoglinger Jana Mooshammer Magdalena Eichmeyer Hannes Peer Andrew Wiering Reinhard Pirstinger Thomas Wall Regina Angerer- COLUMBIA ARTISTS Yuko Kana-Buchmann Philipp Preimesberger BrUndlinger MANAGEMENT LLC Gorda na Pi rsti nger Tour Direction: Gudrun Geyer Double Basses Trombones R. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Wedding Ceremonies

Weddings Rev. William A. Moffitt, D.D. Wedding Ceremonies And More Compiled by Reverend William Moffitt, D.D. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 GENERAL INFORMATION ON CEREMONIES ....................................................... 2 THE MARRIAGE LICENSE. ........................................................................................ 3 REGULAR MARRIAGE LICENSE .............................................................................. 3 CONFIDENTIAL MARRIAGE LICENSE .................................................................... 4 THE RECEPTION .......................................................................................................... 5 PHOTOGRAPHERS AND VIDEOGRAPHERS ............................................................. 8 CLOTHES..................................................................................................................... 10 TRANSPORTATION ................................................................................................... 11 FLOWERS .................................................................................................................... 12 MUSIC .......................................................................................................................... 12 MASTER OF CEREMONIES ....................................................................................... 12 PROFESSIONAL WEDDING CONSULTANTS .......................................................