Fritz Lang: a “Dark Mirror” to Germany and America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

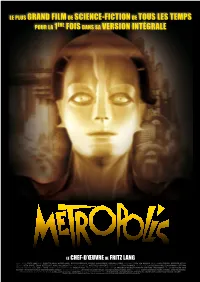

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM

Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM ISSN 1554-6985 VOLUME XI · (/current) NUMBER 2 SPRING 2018 (/previous) EDITED BY (/about) Christy Desmet and Sujata (/archive) Iyengar CONTENTS On Gottfried Keller's A Village Romeo and Juliet and Shakespeare Adaptation in General (/783959/show) Balz Engler (pdf) (/783959/pdf) "To build or not to build": LEGO® Shakespeare™ Sarah Hatchuel and the Question of Creativity (/783948/show) (pdf) and Nathalie (/783948/pdf) Vienne-Guerrin The New Hamlet and the New Woman: A Shakespearean Mashup in 1902 (/783863/show) (pdf) Jonathan Burton (/783863/pdf) Translation and Influence: Dorothea Tieck's Translations of Shakespeare (/783932/show) (pdf) Christian Smith (/783932/pdf) Hamlet's Road from Damascus: Potent Fathers, Slain Yousef Awad and Ghosts, and Rejuvenated Sons (/783922/show) (pdf) Barkuzar Dubbati (/783922/pdf) http://borrowers.uga.edu/7168/toc Page 1 of 2 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM Vortigern in and out of the Closet (/783930/show) Jeffrey Kahan (pdf) (/783930/pdf) "Now 'mongst this flock of drunkards": Drunk Shakespeare's Polytemporal Theater (/783933/show) Jennifer Holl (pdf) (/783933/pdf) A PPROPRIATION IN PERFORMANCE Taking the Measure of One's Suppositions, One Step Regina Buccola at a Time (/783924/show) (pdf) (/783924/pdf) S HAKESPEARE APPS Review of Stratford Shakespeare Festival Behind the M. G. Aune Scenes (/783860/show) (pdf) (/783860/pdf) B OOK REVIEW Review of Nutshell, by Ian McEwan -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Recoding Life; Information and the Biopolitical

Recoding Life This book addresses the unprecedented convergence between the digital and the corporeal in the life sciences and turns to Foucault’s biopolitics in order to understand how life is being turned into a technological object. It examines a wide range of bioscientific knowledge practices that allow life to be known through codes that can be shared (copied), owned (claimed, and managed) and optimised (remade through codes based on standard language and biotech engineering visions). The book’s approach is captured in the title, which refers to ‘the biopolitical’. The authors argue that through discussions of political theories of sovereignty and related geopolitical conceptions of nature and society, we can understand how crucially important it is that life is constantly unsettling and disrupting the established and familiar ordering of the material world and the related ways of thinking and acting politically. The biopolitical dynamics involved are conceptualised as the ‘metacode of life’, which refers to the shifting configurations of living materiality and the merging of conventional boundaries between the natural and artificial, the living and non-living. The result is a globalising world in which the need for an alternative has become a core part of its political and legal instability, and the authors identify a number of possible alternative platforms to understand life and the living as framed by the ‘metacodes’ of life. This book will appeal to scholars of science and technology studies, as well as scholars of the sociology, philosophy, and anthropology of science, who are seeking to understand social and technical heterogeneity as a characteristic of the life sciences. -

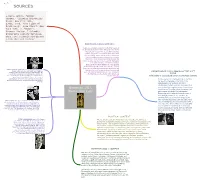

Metropolis, 1927, Director: Fritz Lang

SOURCES 1.Kaes, Anton, *Weimar Cinema,* Columbia University Press: New York 2009. 2.Ott, Fred, *The Films of Fritz Lang*, Lyle Stuart: New York 1979. 3. "Women's Pioneer Project," Columbia University Library Services, wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pionee r/ccp-thea-von-harbou/ SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT Inspired, according to Lang, by his first impression of the Manhattan skyline in 1924, Metropolis was written in 1924 and released nine years after Germany's defeat in World War I, and like all great sci-fi films, reflects both the hopes and the fears of a turbulent society heading towards modernization. In part a meditation on the future relationship between the human and the machine in this modernity. Metropolis is "a great cinematic document of German Expressionism" which "fulfilled the expressionist Weltanschauung that a work of art should [...] finally propound the belief that through the destruction and BRIGITTE HELM, 1906-1996, star of Metropolis (along with rebirth of the world, a new and pure humanity will Gustav Frolich as Feder and Rudolf Klein Rogge as CINEMATOGRAPHY IN CHANGING OF THE SHIFT Rotwang, who also played Caligari in The Cabinet of Dr. arise: the dawn of the Kingdom of Love," while also Caligari and Dr. Mabuse in Dr. Mabuse the Gambler and reflecting that era's fascination with cubism and SCENE The Testament of Dr. Mabuse) in which she played both the futurism (Ott 124). (relationship of sociocultural context to cinematic element) good-hearted working girl Maria and her evil robot doppleganger. One of the most startling and memorable In this scene from the beginning of the film, scenes in the movie is her mesmerizing, lascivious dance in a brothel. -

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) FIONA FORD, MA Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis discusses the film scores of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930), composed in Berlin and London during the period 1926–1930. In the main, these scores were written for feature-length films, some for live performance with silent films and some recorded for post-synchronized sound films. The genesis and contemporaneous reception of each score is discussed within a broadly chronological framework. Meisel‘s scores are evaluated largely outside their normal left-wing proletarian and avant-garde backgrounds, drawing comparisons instead with narrative scoring techniques found in mainstream commercial practices in Hollywood during the early sound era. The narrative scoring techniques in Meisel‘s scores are demonstrated through analyses of his extant scores and soundtracks, in conjunction with a review of surviving documentation and modern reconstructions where available. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding my research, including a trip to the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt. The Department of Music at The University of Nottingham also generously agreed to fund a further trip to the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and purchased several books for the Denis Arnold Music Library on my behalf. The goodwill of librarians and archivists has been crucial to this project and I would like to thank the staff at the following institutions: The University of Nottingham (Hallward and Denis Arnold libraries); the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt; the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; the BFI Library and Special Collections; and the Music Librarian of the Het Brabants Orkest, Eindhoven. -

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May Be Used for Personal Purporses Only Or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 Associated to Dandelon.Com Network

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 associated to dandelon.com network. Mit Beiträgen von Frieda Grafe Enno Patalas Hans Helmut Prinzler Peter Syr (Fotos) Carl Hanser Verlag Inhalt Für Fritz Lang Einen Platz, kein Denkmal Von Frieda Grafe 7 Kommentierte Filmografie Von Enno Patalas 83 Halbblut 83 Der Herr der Liebe 83 Der goldene See. (Die Spinnen, Teil 1) 83 Harakiri 84 Das Brillantenschiff. (Die Spinnen, Teil 2) 84 Das wandernde Bild 86 Kämpfende Herzen (Die Vier um die Frau) 86 Der müde Tod 87 Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler 88 Die Nibelungen 91 Metropolis 94 Spione 96 Frau im Mond 98 M 100 Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse 102 Liliom 104 Fury 105 You Only Live Once. Gehetzt 106 You and Me [Du und ich] 108 The Return of Frank James. Rache für Jesse James 110 Western Union. Überfall der Ogalalla 111 Man Hunt. Menschenjagd 112 Hangmen Also Die. Auch Henker sterben 113 Ministry of Fear. Ministerium der Angst 115 The Woman in the Window. Gefährliche Begegnung 117 Scarlet Street. Straße der Versuchung 118 Cloak and Dagger. Im Geheimdienst 120 Secret Beyond the Door. Geheimnis hinter der Tür 121 House by the River [Haus am Fluß] 123 American Guerrilla in the Philippines. Der Held von Mindanao 124 Rancho Notorious. Engel der Gejagten 125 Clash by Night. Vor dem neuen Tag 126 The Blue Gardenia. Gardenia - Eine Frau will vergessen 128 The Big Heat. Heißes Eisen 130 Human Desire. Lebensgier 133 Moonfleet. Das Schloß im Schatten 134 While the City Sleeps. -

Film Noir: the Most American Film Genre

10/22/2019 FILM NOIR: THE MOST AMERICAN FILM GENRE THE WORLD ACCORDING TO FILM NOIR •“The most American ROGER film genre, because no EBERT: society could have created a world so filled with doom, fate, fear and betrayal, unless it were essentially naive and optimistic.” 1 10/22/2019 THE WORLD ACCORDING TO FILM NOIR The following slides will give you some descriptions of the world as it is portrayed in film noir. • Sam Spade (the detective) tells his client, Bridget O'Shaughnessy, an anecdote about a man named Flitcraft who one day suddenly went missing. • Spade, hired by Flitcraft's wife, is unable to locate him. A few years later, quite by accident, he encounters Flitcraft in another town and then discovers what had caused his disappearance. T 2 10/22/2019 ON THE DAY OF HIS DISAPPEARANCE, FLITCRAFT, WALKING BACK FROM LUNCH, HAD ALMOST BEEN KILLED BY A FALLING BEAM. STRUCK SUDDENLY BY THE ABSURDITY OF HOW EASILY HIS LIFE COULD HAVE BEEN ENDED •(“He knew then that men died at haphazard like that, and lived only while blind chance spared them”), 3 10/22/2019 •he walks away from his job and marriage and all his responsibilities. He settles in another town and after a period of time, rebuilds his life in the same mold as before the incident with the falling beam. • According to Foster Hirsch in Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen: “Like Flitcraft, Spade is clear-sighted --- pitilessly so, in fact --- proceeding as if the world makes sense and adds up to something when he knows it really doesn't. -

Declare Your Party: Posthumus Applauds School Anti-Drug Effort

25C «M0 « S9NJ' BOOK MJCHICAN The Lowell ledger ••••••BBaaaaaBMBBaaaaaMagBaag^MBBaBaaaaaBsasBBBsaaB Cy—b™ Volume 15, Issue 10 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, January 15,1992 Along Main Street Lowell begins transition from conventional to Vista Schools are asked to replace a bus at seven years of use. Despite the purchases Lowell still is not on a replacement Larry Mikulski, Director of Transpoitation at Lowell schedule. This becomes evident when Mikulski indicates that Schools will tell you that doesn't happen at very many the school is still maintaining buses with over 160,000 miles schools. to keep them on the road. HlBel "Lowell Schools is currently replacing buses after 11 years "The buses we purchased are expected to last 12 years. That of use," Mikulski said. "Most schools don't have the money is quite an improvement compared to just seven years ago," he to replace a bus after seven years." said. Lowell Board of Education member Chris Van Antwerp applauded the school systems concern for safety through the Declare your party: life of a bus. "That cannot be overemphasized. You can't put LIBRARY BRANCH CLOSINGS a price on safety." Only registered voters who AtMonday night's January Board meeting, Lowell's School All 17 branches of the Kent County Library System will be Board approved the purchase of three 71 passenger buses and declare party can vote in primary closed Friday, January 31,1992 for staff in-service training. one 48 passenger bus. Michigan will conduct ics However, only registered This includes the Lowell and Alto branch.