1. the Origins of the Labour Party - Myths and Reality by W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Harold Wilson Obituary

Make a contribution News Opinion Sport Culture Lifestyle UK World Business Football UK politics Environment Education Society Science Tech More Harold Wilson obituary Leading Labour beyond pipe dreams Geoffrey Goodman Thu 25 May 1995 09.59 EDT 18 Lord Wilson of Rievaulx, as he came improbably to be called - will not go down in the history books as one of Britain's greatest prime ministers. But, increasingly, he will be seen as a far bigger political figure than contemporary sceptics have allowed far more representative of that uniquely ambivalent mood of Britain in the 1960s and a far more rounded and caring, if unfulfilled, person. It is my view that he was a remarkable prime minister and, indeed, a quite remarkable man. Cynics had a field day ridiculing him at the time of his decline. Perhaps that was inevitable given his irresistible tendency to behave like the master of the Big Trick in the circus ring of politics - for whom there is nothing so humiliating as to have it demonstrated, often by fellow tricksters, that the Big Trick hasn't worked. James Harold Wilson happened to be prime minister leading a left wing party at a time when the mores of post-war political and economic change in Britain (and elsewhere) were just beginning to be perceived. Arguably it was the period of the greatest social and industrial change this century, even if the people - let alone the Wilson governments - were never fully aware of the nature of that change. Social relationships across the entire class spectrum were being transformed. -

Fielding Prelims.P65

7 Instilling ‘responsibility’ in the young If only for reasons of self-preservation, Labour was obliged to draw some young people into the party so they could eventually replace its elderly stalwarts.1 Electoral logic also dictated that Labour had to ensure the support of at least a respectable proportion of what was an expand- ing number of voters. Consequently, the 1955 Wilson report on party organisation (see Chapter 2) expressed particular concern about the consequences of Labour’s inability to interest youngsters in the party.2 Many members were, however, uncertain about the purpose, manner and even merit of making a special appeal to the young. The 1960s began with commentators asserting that most young adults were materi- ally satisfied and so inclined to Conservatism, but the decade ended with the impression that many young people had become alienated from society and embraced far-left causes. This shift in perceptions did not exactly help clarify thinking. Those who have analysed Labour’s attempt to win over the young tend to blame the party’s apparent refusal to take their concerns seriously for its failure to do so.3 They consider Labour’s prescriptive notions of how the young should think and act inhibited its efforts. In particular, at the start of the decade the party’s ‘residual puritanism’ is supposed to have prevented it evoking a positive response among purportedly hedonistic proletarians.4 At the end of the 1960s, many believed the government’s political caution had estranged middle-class students.5 This chapter questions the exclusively ‘supply-side’ explan- ation of Labour’s failure evident in such accounts. -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

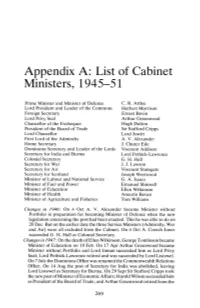

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

Or the Not So 'Strange Death' of Liberal Wales

Article A ‘Strange Death’ Foretold (or the Not So ‘Strange Death’ of Liberal Wales): Liberal Decline, the Labour Ascendancy and Electoral Politics in South Wales, 1922- 1924 Meredith, Stephen Clive Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/4392/ Meredith, Stephen Clive ORCID: 0000-0003-2382-1015 (2012) A ‘Strange Death’ Foretold (or the Not So ‘Strange Death’ of Liberal Wales): Liberal Decline, the Labour Ascendancy and Electoral Politics in South Wales, 1922- 1924. North American Journal of Welsh Studies, 7 (-). pp. 18-37. ISSN 15548112 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. - For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk A ‘STRANGE DEATH’ FORETOLD (OR THE NOT SO ‘STRANGE DEATH’ OF LIBERAL WALES): LIBERAL DECLINE, THE LABOUR ASCENDANCY AND ELECTORAL POLITICS IN SOUTH WALES, 1922-1924 Stephen Meredith Abstract This essay revisits debates concerning the rapid decline of the historic and once powerful Liberal Party and its replacement by the Labour Party as the main anti-Conservative, progressive party of the state around the fulcrum of the First World War. -

Malice in the Cotswolds PDF Book

MALICE IN THE COTSWOLDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rebecca Tope | 414 pages | 15 Jun 2013 | ALLISON & BUSBY | 9780749012335 | English | London, United Kingdom Malice in the Cotswolds PDF Book Thea is convinced that the single mother, Gudrun, is not responsible and sets out on a crusade to exonerate her. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. She is also very odd. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. Languages English. That sounds worthy but the problem is the system, as now agreed by Parliament, may result in exactly the opposite of what Leveson intended. Get a card. The book ended abruptly and unsatisfactorily, given the endless buildup. Add a card Contact support Cancel. Details if other :. We follow her experiences and observations from there on. Mydworth is a sleepy English market town just 50 miles from London. Try refreshing the page. Want to Read saving…. Hoping to stumble upon a new author or series? The US has an advantage over the UK in that its written constitution and bill of rights protects freedom of speech and the press. I travel quite extensively, too. The following day Thea discovers the body of little Stevie Horsfall behind her car which she had left parked outside the cottage. Subscribe to: Post Comments Atom. Original Title. A local boy, Stevie Horsfall, is found brutally strangled, with his mother as prime suspect. Cancel anytime. Home 1 Books 2. Along with her spaniel, Hepzie, Thea finds herself in the village of Chedworth. Monday, 16 February Rebecca Tope. Pay using card ending in. -

Spelman's Political Warriors

SPELMAN Spelman’s Stacey Abrams, C’95 Political Warriors INSIDE Stacey Abrams, C’95, a power Mission in Service politico and quintessential Spelman sister Kiron Skinner, C’81, a one-woman Influencers in strategic-thinking tour de force Advocacy, Celina Stewart, C’2001, a sassy Government and woman getting things done Public Policy THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE | SPRING 2019 | VOL. 130 NO. 1 SPELMAN EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Renita Mathis Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs COPY EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Beverly Melinda James Atlanta, GA 30314 OR http://www.spelmanlane.org/SpelmanMessengerSubmissions GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Submission Deadlines: Fall Issue: Submissions Jan. 1 – May 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER Spring Issue: Submissions June 1 – Dec. 31 Danielle K. Moore ALUMNAE NOTES EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: Jessie Brooks • Education Joyce Davis • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Sharon E. Owens, C’76 • Professional Jane Smith, C’68 Please include the date of the event in your submission. TAKE NOTE! EDITORIAL INTERNS Take Note! is dedicated to the following alumnae Melody Greene, C’2020 achievements: Jana Hobson, C’2019 • Published Angelica Johnson, C’2019 • Appearing in films, television or on stage Tierra McClain, C’2021 • Special awards, recognition and appointments Asia Riley, C’2021 Please include the date of the event in your submission. WRITERS BOOK NOTES Maynard Eaton Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae and faculty authors. Connie Freightman Please submit review copies. Adrienne Harris Tom Kertscher IN MEMORIAM We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive notice Alicia Lurry of the death of a Spelman sister, please contact the Kia Smith, C’2004 Office of Alumnae Affairs at 404-270-5048 or Cynthia Neal Spence, C’78, Ph.D. -

Co-Operatives, a Post War Opportunity Missed

Co -operation A post-war opportunity missed? A Welsh perspective Alun Burge 1 Co -operation A post-war opportunity missed? A Welsh perspective Alun Burge Alun Burge worked with agricultural co-operatives in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Peru in the 1980s and 1990s. He joined the Department of Social Justice of the Welsh Government in 2002, where he worked for ten years. He is writing a history of the co-operative movement in South Wales. This is a revised and updated version of the paper ‘Nationalisation, Voluntarism and the Welfare State: A Co-operative View of Collective Organisation and Socialised Services, 1945-59’, which was presented at the Comparing Coalfields in Britain and Japan Symposium , Gregynog, March 2011. The Wales Co-operative Centre The Wales Co-operative Centre is pleased to sponsor this Bevan Foundation publication. The Centre was set up 30 ago and ever since we’ve been helping businesses grow, people to find work and communities to tackle the issues that matter to them. Our advisors work co-operatively across Wales, providing expert, flexible and reliable support to develop sustainable businesses and strong, inclusive communities. 2012 marks our thirtieth anniversary as well as the United Nations International Year of Co-operatives. Wales Co-operative Centre Llandaff Court Fairwater Road Cardiff CF5 2XP Tel: 0300 111 5050 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @WalesCoOpCentre Facebook: Wales Co-operative Centre The Bevan Foundation The Bevan Foundation is the only charity in Wales committed to tackling all aspects of poverty, inequality and injustice. As an independent, influential charity we shape government policy, inform public opinion and inspire others into action. -

Milovan Djilas and the British Labour Party, 1950–19601

58 Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino LVIII – 3/2018 1.01 UDC :929DJILAS M.:329(410)LAB»1950/1960« Mateja Režek* Milovan Djilas and the British Labour Party, 1950–19601 IZVLEČEK MILOVAN ĐILAS IN BRITANSKA LABURISTIČNA STRANKA, 1950–1960 Članek obravnava politično preobrazbo Milovana Đilasa skozi analizo njegovih stikov z britanskimi laburisti in odziv Laburistične stranke na afero Đilas. Po sporu z Informbirojem so jugoslovanski voditelji skušali vzpostaviti alternativne mednarodne povezave tudi prek zahodnih socialdemokratskih in socialističnih strank, kot najprimer- nejši partner pa se je pokazala britanska Laburistična stranka. Uradni stiki z njo so bili vzpostavljeni leta 1950, ključno vlogo v dialogu z britanskimi laburisti pa je odigral pred- sednik Komisije za mednarodne odnose CK ZKJ Milovan Đilas. Po njegovi odstranitvi iz političnega življenja in obsodbi na zaporno kazen so se nekoč topli odnosi med britanskimi laburisti in jugoslovanskimi komunisti sicer ohladili, vendar vodstvo Laburistične stranke ni želelo tvegati poslabšanja odnosov z Jugoslavijo, zato se je na afero Đilas odzivalo zelo previdno. Čeprav je Jugoslavija ostajala avtoritarna država pod vodstvom komunistične partije, je v očeh Zahoda še vedno predstavljala pomemben dejavnik destabilizacije vzho- dnega bloka, prijateljski odnosi med Laburistično stranko in jugoslovanskimi komunisti pa so temeljili predvsem na zunanjepolitičnih interesih obeh strani. V drugi polovici petdesetih let je pragmatični geopolitični premislek povsem prevladal nad ideološko afiniteto: zani- -

294 Peter Catterall As Nonconformity Gently Waned, the Labour Party

294 book reviews Peter Catterall Labour and the Free Churches, 1918–1939. Radicalism, Righteousness and Religion. Bloomsbury, London/New York 2016, xiv + 322 pp. isbn 9781441115898. £63; us$85.40. As nonconformity gently waned, the Labour Party waxed. This meticulously researched, perceptive, and subtle study charts the mingling of those two jour- neys between 1918 and 1939. The distinctiveness of the relationship between British religion and socialism has fascinated historians since Halévy’s con- troversial suggestion that evangelical religion (and particularly Methodism) staved off a French style revolution. Indeed, Catterall’s starting point is the oft-quoted comment of Morgan Phillips, the general secretary of the Labour Party 1944–1961, that socialism in Britain owed more to Methodism than Marx, and that therein lay its distinctiveness from its European anti-clerical cousins. Harold Wilson, a Congregationalist by upbringing, suggested that the allit- eration bred inaccuracy and ‘nonconformity’ would be better, but the point remains. As Catterall makes clear, during the interwar years, various brands of Methodism provided far more Labour mps and activists than the other Free Churches. Catterall uses “four prisms” to gain data about the relationship between the Free Churches and Labour—the attitude of Free Church leaderships to the party, local patterns of commitment and voting behaviour, the person- nel of the Labour movement, and ideas and ideals of both. Undergirding this is research into the denominational allegiance of mps, tuc General Council members, National Executive Committee members and the Labour councillors of Bolton, Liverpool, Bradford, and Norfolk.The mixed nature of the sources for all but mps means that the edges will always be fuzzy, but his instinct is to be inclusive—upbringing and ethos are as determinative as adult commitment.