NBC: America's Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Women's Performances of Sexuality

“DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performances of Sexuality Copyright 2012 Evleen Michelle Nasir “DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Harry Berger Alfred Bendixen Head of Department, Judith Hamera August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performance of Sexuality. (August 2012) Evleen Michelle Nasir, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen There is a discursive formation of incapability that surrounds senior women’s sexuality. Senior women are incapable of reproduction, mastering their bodies, or arousing sexual desire in themselves or others. The senior actresses’ I explore in the case studies below insert their performances of self and their everyday lives into the large and complicated discourse of sex, producing a counter-narrative to sexually inactive senior women. Their performances actively embody their sexuality outside the frame of a character. This thesis examines how senior actresses’ performances of sexuality extend a discourse of sexuality imposed on older woman by mass media. These women are the public face of senior women’s sexual agency. -

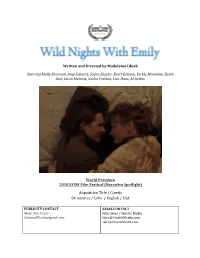

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools

RESEARCH REPORT NOVEMBER 2014 Looking Forward to High School and College Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools Elaine M. Allensworth, Julia A. Gwynne, Paul Moore, and Marisa de la Torre TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary Chapter 5 55 Who Is at Risk of Earning Less 7 Introduction Than As or Bs in High School? Chapter 1 Chapter 6 17 Issues in Developing and Indicators of Whether Students Evaluating Indicators 63 Will Meet Test Benchmarks Chapter 2 Chapter 7 23 Changes in Academic Performance Who Is at Risk of Not Reaching from Eighth to Ninth Grade 75 the PLAN and ACT Benchmarks? Chapter 3 Chapter 8 29 Middle Grade Indicators of How Grades, Attendance, and High School Course Performance 81 Test Scores Change Chapter 4 Chapter 9 47 Who Is at Risk of Being Off-Track Interpretive Summary at the End of Ninth Grade? 93 99 References 104 Appendices A-E ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this work. We thank Robert Balfanz and Julian Betts for providing us with very thoughtful review and feedback which were used to revise this report. We also thank Mary Ann Pitcher and Sarah Duncan, at the Network for College Success, and members of our Steering Committee, especially Karen Lewis, for their valuable feedback. Our colleagues at UChicago CCSR and UChicago UEI, including Shayne Evans, David Johnson, Thomas Kelley-Kemple, and Jenny Nagaoka, were instrumental in helping us think about the ways in which this research would be most useful to practitioners and policy makers. -

May 16, 2014 WFAN's BOOMER & CARTON TEAM

May 16, 2014 WFAN’S BOOMER & CARTON TEAM UP WITH GIN BLOSSOMS ON MAY 23 FOR THE ‘SUMMER KICKOFF PARTY’ AT D’JAIS IN BELMAR, NEW JERSEY WFAN-AM/FM is counting down the days to summer and planning an exciting celebration to kick it off in style, with a live broadcast from morning show hosts Boomer & Carton at D’JAIS on Ocean Avenue in Belmar, New Jersey. Next Friday, May 23, Boomer Esiason & Craig Carton will host their inaugural Memorial Day “Summer Kickoff Party” with a live broadcast from 6AM – 10AM. In addition, there will be live performances by the GRAMMY® nominated band Gin Blossoms and special guests on-air during the show. Admission to the public is free, and the WFAN fan van crew will be on hand with giveaways. Tune in to WFAN on-air, streaming online at www.wfan.com and through the Radio.com app for mobile devices to hear Boomer & Carton and Gin Blossoms live from D’JAIS. Boomer & Carton – Broadcast on-air and online from 6 a.m. – 10 a.m. ET and simulcast on CBS Sports Network, the show features former NFL quarterback Boomer Esiason and radio veteran Craig Carton discussing New York sports talk with sports icons, league personnel, and a variety of national celebrities from the entertainment and music industries. For more than two decades, Gin Blossoms have defined the sound of jangle pop. From their late 80s start as Arizona’s top indie rock outfit, the Tempe-based combo has drawn critical applause and massive popular success for their trademark brand of chiming guitars, introspective lyricism, and irresistible melodies. -

Ms Girls Athletics Info

Commerce Middle School Lady Tiger Athletics Welcome to middle school athletics! We are super excited to get the year started and to get to know your daughter(s) throughout the year. Commerce ISD has issued the following statement “In order for your daughter to participate in UIL events and/or extra-curricular activities, your daughter has to follow the Hybrid model. If your daughter is strictly online, she cannot participate in any UIL event or extra curricular activities.” We will continue to have practice EVERY morning at 6:45 a.m. throughout the year. If your daughter is playing Volleyball, she will be here every morning, ready to practice at 6:45. If your daughter is in Athletics and NOT playing volleyball, she will still need to come to Athletics every morning, ready to start at 7:30 a.m. Parents will have to provide transportation to and from practice. If it is not your daughter’s assigned day to be at school, she will need to be picked up at the end of practice. Contacts: CMS: (903)-886-3795 ext. 726 Julie Brown: 8th(Basketball)/8th (Volleyball)Grade Coach- [email protected] Kayla Collum:7th(Volleyball/Track)/7th(Basketball/Track) Coach- [email protected] Tony Henry: Head Basketball Coach- [email protected] Shelley Jones: Head Volleyball/Track Coach- [email protected] Amanda Herron: Athletic Trainer- [email protected] Jeff Davidson: Athletic Director- [email protected] Coach Brown will set up a Remind for 7th and 8th Grade Girls Athletics. All information and Updated information will be found on Remind for students and parents will be on Remind. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development's Next Wave Intro

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development’s Next Wave Intro In spring of 2015, LISC NYC’s Executive Director, Sam Marks invited friends of LISC - top economists, policy analysts, journalists, community development gurus and current leaders of some of the city’s top community development corporations - to join staff in strategizing around critical questions facing New York’s community development sector. What can LISC NYC and its community development partners do to counter global and national trends exacerbating economic polarization? What is community development’s role in shaping the city’s upcoming neighborhood rezonings, preserving affordable housing, and, building human capital? How can the industry scale up even as it consolidates and redeploys resources to new areas and programming? Over the course of three panel discussions moderated by Marks, presenters and LISC NYC staff shed some light on next wave strategies for New York City’s neighborhoods. Panel 1: Global City/Global Trends: Panelists explained the global trends driving high real estate prices, economic polarization, gentrification and displacement and debated about the levers available to city government, LISC NYC and community developers to alleviate the harsh impacts on low and moderate income New Yorkers. Jonathan Bowles, Executive Director, Center for an Urban Future . Adam Davidson, co-founder and co-host, Planet Money . Ingrid Gould Ellen, Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Director of the Urban Planning Program, New York University Wagner; Faculty Director, Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy . Chris Herbert, Managing Director, Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies Panel 2: Community development past, present and future: Former LISC NYC directors distilled their experiences using real estate strategies to address neighborhood issues and considered strategies to meet current challenges. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Community Rebranding: a Case Study

COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Hospitality Management By Michelle L. Pecheck Spring 2015 SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY AUTHOR: Michelle L. Pecheck DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2015 The Collins College of Hospitality Management Dr. Ed Merritt _________________________________________ Project Committee Chair Associate Professor Dr. Margie Jones _________________________________________ Associate Professor Dr. Neha Singh _________________________________________ Director of Graduate Studies Associate Professor ii ABSTRACT Intro: This case study profiles Claremont, a city of approximately 37,000 residents. Since its formation in 1887, it has primarily been known as a college town with a history of citrus production. This case study investigates what components would need to be in place to rebrand or reposition the city as a unique, healthful destination. Case: A resident survey, interviews, and focus groups were used to gather qualitative data about residents’ perceptions of the city’s current brand and potential rebranding. Management & Outcome: Scope of work for the focus city included data gathering from residents, and identification of projects, services, and designations to support marketing of the city as a health/wellness destination. Discussion: Data from surveys, focus groups, and key informant interviews indicated that residents were uncertain of the City’s current brand, in general appeared to care little about the brand, and lacked information about the City’s interest in a possible future rebranding. Further, City documents revealed a history of departmental rebrandings that may have obscured the City’s current brand image. -

“Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”—Rudy Vallee (1932) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Doris Bickford-Swarthout (Guest Post)*

“Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”—Rudy Vallee (1932) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Doris Bickford-Swarthout (guest post)* Rudy Vallee The writers said this song was not meant to be a sentimental piece or one for begging. It expressed the frustration, anger and puzzlement of millions of the unemployed and hungry. When the Great Depression hit, working-class veterans of World War I were especially harmed. Back from the war with injuries and loss, they tried to rebuild their lives, only to find, suddenly, that there were no jobs and for many, no homes. Why, they ask? They used to tell me I was building a dream And so I followed the mob When there was earth to plow or guns to bear I was always there right on the job. They used to tell me I was building a dream With peace and glory ahead Why should I be standing in line Just waiting for bread? Once I built a railroad, I made it run Made it race against time Once I built a railroad, now it's done Brother, can you spare a dime? Once I built a tower up to the sun Brick and rivet and lime Once I built a tower, now it's done Brother, can you spare a dime? Rudy Vallee was born Hubert Prior Vallée, July 28, 1901, at Island Pond, Vermont. His family moved to Westport, Maine, where he grew up. His earliest ambition was to play the saxophone in a band. He was a pupil of Rudy Wiedoeft, whom he admired so much that his friends began calling him “Rudy.” The name stuck, and the only time Valle used his birth name was during World War II when he served in the Coast Guard. -

Shuttlegirl Julie Anne Comine Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 Shuttlegirl Julie Anne Comine Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Comine, Julie Anne, "Shuttlegirl" (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14435. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shuttlegirl by Julie Anne Comine A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Neal Bowers Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1998 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Julie Anne Comine has met the thesis requirements ofIowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy lU for Jeff, with great impatience IV TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Astronaut's Bride 1 The married planet 2 Reputation 3 hoopskirt 4 The Godmother, part 3 1/2 7 To the memory of Mrs. Seuss 8 Canticle of tentacles 9 The torch singer who came in from the cold 10 Sarcastics anonymous 11 dada 12 Decree 13 Breaking down is hard to do 16 The book of Sarah 17 Hymns & hers 19 Diadem 20 II. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Who We Are

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Who We Are The BBG is the independent federal government agency that oversees all U.S. civilian international media. This includes the Voice of America, Radio Estonia Russia Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the Latvia Office of Cuba Broadcasting, Radio Lithuania Belarus Free Asia, and the Middle East Ukraine Kazakhstan Broadcasting Networks, along with Moldova Bosnia-Herz. Serbia Kosovo Georgia Uzbekistan the International Broadcasting Mont. Macedonia Armenia Kyrgyzstan Turkey Azerbaijan Turkmenistan Albania Tajikistan Bureau. BBG is also the name of the Lebanon North Korea Tunisia Pal. Ter. Syria Afghanistan China board that governs the agency. Morocco West Bank & Gaza Iraq Iran Jordan Kuwait Algeria Libya Egypt Pakistan Western Sahara Saudi Bahrain Mexico Cuba Qatar Bangladesh Taiwan BBG networks are trusted news Haiti Arabia U.A.E. Burma Dominican Mauritania Mali Laos Cape Verde Oman sources, providing high-quality Honduras Republic Senegal Niger Sudan Eritrea Guatemala The Gambia Burkina Chad Yemen Thailand Vietnam Phillipines Nicaragua Guinea-Bissau Faso Djibouti journalism and programming to more El Salvador Venezuela Guinea BeninNigeria Cambodia Costa Rica Sierra Leone Ghana Central South Ethiopia Panama Liberia Afr. Rep. Sudan Somalia Togo Cameroon Singapore than 215 million people each week. Colombia Cote d’Ivoire Uganda Equatorial Guinea Congo Dem. Rep. Seychelles Ecuador Sao Tome & Principe Rwanda They are leading channels for Of Congo Burundi Kenya Gabon Indonesia information about the United States Tanzania Comoros Islands Peru Angola Malawi as well as independent platforms for Zambia Bolivia Mozambique Mauritius freedom of expression and free press. Zimbabwe Paraguay Namibia Botswana Chile Madagascar Mission: To inform, engage and connect people around the Swaziland South Lesotho Uruguay Africa world in support of freedom and democracy.