Corvus Review Issue 9W (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Channels, May 26-June 1

MAY 26 - JUNE 1, 2019 staradvertiser.com BRIDGING THE GAP The formula of the police procedural gets a spiritual new twist on The InBetween. The drama series follows Cassie Bedford (Harriet Dyer), who experiences uncontrollable visions of the future and the past and visits from spirits desperately seeking her help. To make use of her unique talents, she assists her father, Det. Tom Hackett (Paul Blackthorne), and his former FBI partner as they tackle complicated crimes. Premieres Wednesday, May 29 on NBC. WE EMPOWER YOUR VOICE, BY EMPOWERING YOU. Tell your story by learning how to shoot, edit and produce your own show. Start your video training today at olelo.org/training olelo.org ON THE COVER | THE INBETWEEN Crossing over Medium drama ‘The As for Dyer, she may be a new face to North first time channelling a cop character; he American audiences, but she has a long list of starred as Det. Kyle Craig in the “Training Day” InBetween’ premieres on NBC acting credits, including dramatic and comedic series inspired by the 2001 film of the same roles in her home country of Australia. She is name. By Sarah Passingham best known for portraying Patricia Saunders in Everything old really is new again. There was TV Media the hospital drama “Love Child” and April in the a heyday for psychic, clairvoyant and medium- cop comedy series “No Activity,” which was centred television in the mid-2000s, with he formula of the police procedural gets a adapted for North American audiences by CBS shows like “Medium” and “Ghost Whisperer,” spiritual new twist when “The InBetween” All Access in 2017. -

GTMO Celebrates 100 Years of Friendship

Vol. 60 No. 05 Friday, January 31, 2003 GTMO Celebrates 100 Years ofFriendship IWA FEW~ 4 410, 1 I amp J In celebration of 100 Years of Friendship, the Cuban American Friendship Day Committee held a Poster and Essay contest for children in grades 3 through 12. Shown above is the Grand Prize poster by fourth grader Megan Landowski. The winning participants will be officially recognized during the Cuban American Friendship Day celebration today at Phillips Park. Come join in the celebration and congratulate the winners. Check out pages 6 and 7 to see all the winning entries. What's Inside Davis Selected for Soldier Shares Musical Officer Program Talents With GTMO * HM1(AW/DV) Christopher Davis of Army Specialist Bryan Randall , aka the Naval Station Dive Locker has Jezt Bryan, gave a crowd-pleasing, been selected to participate in the hip-hop and R&B performance at the Medical Enlisted Commissioning Windjammer last Friday. Program. See page 4. See page 8 . J1 GUANTANAMO SAY | Force Are Protection You Visible or Invisible? from the NAVSTA Safety Office scooters and bicycles. Instruct children not As you travel the roads of the Guantanamo * DOT approved helmet, long sleeved shirt or to open doors to Bay community carrying out your daily routine, jacket, ANSI approved eye/face protection, long pants, strangers. While we have you ever thought to yourself, AM I full fingered gloves, full foot hard sole shoes are isolated here in HIGHLY VISIBLE OR INVISIBLE? * Reflective vest during dark hours or reduced If not, maybe you should. What would your visibility GTMO, bad habits answer be to this question? What does it take to * Headlight and taillight on at all times can develop that be highly visible? * Using proper turn signals and remembering to carry to your next Biking turn them off when not needed assignment. -

TV Listings FRIDAY, MARCH 11, 2016

TV listings FRIDAY, MARCH 11, 2016 01:05 Art Attack 15:00 I Hate My Teenage Daughter 01:30 Henry Hugglemonster 15:30 Suburgatory 01:45 Calimero 16:00 The Nightly Show With Larry 02:00 Zou Wilmore 02:15 Loopdidoo 16:30 Mad Love 02:30 Art Attack 17:00 Late Night With Seth Meyers 02:55 Henry Hugglemonster 18:00 Fresh Off The Boat 03:05 Calimero 18:30 Black-Ish 03:20 Zou 19:00 Parks And Recreation 03:30 Loopdidoo 19:30 The Simpsons 03:45 Art Attack 20:00 The Tonight Show Starring 04:10 Henry Hugglemonster Jimmy Fallon 04:20 Calimero 21:00 Suburgatory 04:35 Zou 21:30 The Nightly Show With Larry 04:45 Loopdidoo Wilmore 05:00 Art Attack 22:00 Community 05:25 Henry Hugglemonster 22:30 Curb Your Enthusiasm 05:35 Calimero 23:00 The League 05:50 Zou 23:30 Late Night With Seth Meyers 06:00 Loopdidoo 06:15 Art Attack 06:35 Henry Hugglemonster 06:50 Calimero 07:00 Zou 07:20 Loopdidoo 07:35 Art Attack 08:00 Calimero 00:00 Pusher 08:10 Zou 02:00 Outpost: Rise Of The 08:25 Loopdidoo Spetsnaz 08:40 Miles From Tomorrow 04:00 The River Wild 09:05 Sofia The First 06:00 47 Ronin 09:30 Goldie & Bear 08:00 Metro 09:45 Jake And The Never Land 10:00 Snitch Pirates 12:00 Toxin 10:10 Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 13:45 47 Ronin 10:35 Doc McStuffins 15:45 King Arthur 11:00 Sofia The First 18:00 Snitch 11:30 Goldie & Bear 20:00 X-Men Origins: Wolverine 12:00 Miles From Tomorrow 22:00 Waist Deep 12:25 Special Agent Oso 12:40 The Hive 12:50 Handy Manny SEVENTH SON ON OSN MOVIES HD 13:15 Jungle Junction 13:30 Mickey Mouse Clubhouse Everything 11:00 The Pioneer Woman 02:30 Big Star’s Little Star Georgia 14:00 Sofia The First 20:55 K. -

Characters Reunite to Celebrate South Dakota's Statehood

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad May 24 - 30, 2019 Buy 1 V A H A G R Z U N Q U R A O C Your Key 2 x 3" ad A M U S A R I C R I R T P N U To Buying Super Tostada M A R G U L I E S D P E T H N P B W P J M T R E P A Q E U N and Selling! @ Reg. Price 2 x 3.5" ad N A M M E E O C P O Y R R W I get any size drink FREE F N T D P V R W V C W S C O N One coupon per customer, per visit. Cannot be combined with any other offer. X Y I H E N E R A H A Z F Y G -00109093 Exp. 5/31/19 WA G P E R O N T R Y A D T U E H E R T R M L C D W M E W S R A Timothy Olyphant (left) and C N A O X U O U T B R E A K M U M P C A Y X G R C V D M R A Ian McShane star in the new N A M E E J C A I U N N R E P “Deadwood: The Movie,’’ N H R Z N A N C Y S K V I G U premiering Friday on HBO. -

1 Production Information in Just Go with It, a Plastic Surgeon

Production Information In Just Go With It, a plastic surgeon, romancing a much younger schoolteacher, enlists his loyal assistant to pretend to be his soon to be ex-wife, in order to cover up a careless lie. When more lies backfire, the assistant's kids become involved, and everyone heads off for a weekend in Hawaii that will change all their lives. Columbia Pictures presents a Happy Madison production, Just Go With It. Starring Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler, Jack Giarraputo, and Heather Parry. Screenplay by Allan Loeb and Timothy Dowling. Based on ―Cactus Flower,‖ Screenplay by I.A.L. Diamond, Stage Play by Abe Burrows, Based upon a French Play by Barillet and Gredy. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Allen Covert, Tim Herlihy, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson-Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Just Go With It has been rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for Frequent Crude and Sexual Content, Partial Nudity, Brief Drug References and Language. The film will be released in theaters nationwide on February 11, 2011. 1 ABOUT THE FILM At the center of Just Go With It is an everyday guy who has let a careless lie get away from him. ―At the beginning of the movie, my character, Danny, was going to get married, but he gets his heart broken,‖ says Adam Sandler. -

Grown-Ups Film Production Notes

PRODUCTION NOTES Release Date: June 24 th , 2010 Running time: 102 min Rating: PG 1 Grown Ups , Starring Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, and Rob Schneider, is a full-on comedy about five men who were best friends when they were young kids and are now getting together with their families on the Fourth of July weekend for the first time in thirty years. Picking up where they left off, they discover that growing older doesn’t mean growing up. Columbia Pictures presents in association with Relativity Media a Happy Madison production, a film by Dennis Dugan, Grown Ups . The film stars Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, Rob Schneider, Salma Hayek, Maria Bello, and Maya Rudolph. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler and Jack Giarraputo. Written by Adam Sandler & Fred Wolf. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Tim Herlihy, Allen Covert, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson- Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Credits are not final and subject to change. 2 ABOUT THE FILM Adam Sandler, Kevin James, Chris Rock, David Spade, and Rob Schneider head up an all-star comedy cast in Grown Ups , the story of five childhood friends who reunite thirty years later to meet each others’ families for the first time. When their beloved former basketball coach dies, they return to their home town to spend the summer at the lake house where they celebrated their championship years earlier. -

DVD LIST 05-01-14 Xlsx

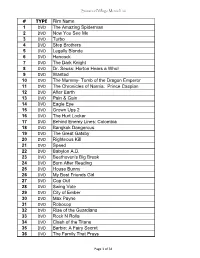

Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 1 DVD The Amazing Spiderman 2 DVD Now You See Me 3 DVD Turbo 4 DVD Step Brothers 5 DVD Legally Blonde 6 DVD Hancock 7 DVD The Dark Knight 8 DVD Dr. Seuss: Horton Hears a Who! 9 DVD Wanted 10 DVD The Mummy- Tomb of the Dragon Emperor 11 DVD The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 12 DVD After Earth 13 DVD Pain & Gain 14 DVD Eagle Eye 15 DVD Grown Ups 2 16 DVD The Hurt Locker 17 DVD Behind Enemy Lines: Colombia 18 DVD Bangkok Dangerous 19 DVD The Great Gatsby 20 DVD Righteous Kill 21 DVD Speed 22 DVD Babylon A.D. 23 DVD Beethoven's Big Break 24 DVD Burn After Reading 25 DVD House Bunny 26 DVD My Best Friends Girl 27 DVD Cop Out 28 DVD Swing Vote 29 DVD City of Ember 30 DVD Max Payne 31 DVD Robocop 32 DVD Rise of the Guardians 33 DVD Rock N Rolla 34 DVD Clash of the Titans 35 DVD Barbie: A Fairy Secret 36 DVD The Family That Preys Page 1 of 34 Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 37 DVD Open Season 2 38 DVD Lakeview Terrace 39 DVD Fire Proof 40 DVD Space Buddies 41 DVD The Secret Life of Bees 42 DVD Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa 43 DVD Nights in Rodanthe 44 DVD Skyfall 45 DVD Changeling 46 DVD House at the End of the Street 47 DVD Australia 48 DVD Beverly Hills Chihuahua 49 DVD Life of Pi 50 DVD Role Models 51 DVD The Twilight Saga: Twilight 52 DVD Pinocchio 70th Anniversary Edition 53 DVD The Women 54 DVD Quantum of Solace 55 DVD Courageous 56 DVD The Wolfman 57 DVD Hugo 58 DVD Real Steel 59 DVD Change of Plans 60 DVD Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 61 DVD Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters 62 DVD The Cold Light of Day 63 DVD Bride & Prejudice 64 DVD The Dilemma 65 DVD Flight 66 DVD E.T. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Senza Titolo

1 COLUMBIA PICTURES Presenta in Associazione con RELATIVITY MEDIA una Produzione HAPPY MADISON un film di DENNIS DUGAN (Grown Ups) ADAM SANDLER KEVIN JAMES CHRIS ROCK DAVID SPADE ROB SCHNEIDE SALMA HAYEK MARIA BELLO MAYA RUDOLPH Supervisione alle musiche MICHAEL DILBECK, BROOKS ARTHUR, KEVIN GRADY Musiche di RUPERT GREGSON-WILLIAMS Costumi di ELLEN LUTTER Montaggio di TOM COSTAN Scenografie di PERRY ANDELIN BLAKE Direttore della fotografia THEO VAN de SANDE Executive Producers BARRY BERNARDI, TIM HERLIHY, ALLEN COVERT, STEVE KOREN Scritto da ADAM SANDLER Prodotto da ADAM SANDLER, JACK GIARRAPUTO Regia di DENNIS DUGAN Data di uscita: 1 ottobre 2010 Durata: 100 minuti sonypictures.it Distribuito da Sony Pictures Releasing Italia 2 CARTELLO DOPPIATORI – UN WEEKEND DA BAMBOCCIONI UFFICIO STAMPA Cristiana Caimmi Dialoghi Italiani Marco Mete Direzione del Doppiaggio Manlio de Angelis Voci Lanny – RICCARDO ROSSI Eric – VITTORIO de ANGELIS Rob – SIMONE MORI Marcus – MASSIMO DE AMBROSIS Kurt – ROBERTO GAMMINO Roxanne – TIZIANA AVARISTA Fonico di Mix Fabio Tosti Fonico di Doppiaggio Walter Mannina Assistente al Doppiaggio Silvia Ferri Doppiaggio eseguito presso CDC SEFIT GROUP 3 Sinossi Un weekend da bamboccioni è una commedia che racconta la storia di cinque amici, vecchi compagni di squadra, che si riuniscono dopo anni per onorare la scomparsa dell’allenatore di basket della loro infanzia. Con mogli e figli, trascorrono insieme il weekend del 4 luglio nella casa sul lago dove anni prima avevano festeggiato la vittoria della squadra. Ricordando le atmosfere del passato, scoprono che crescere non significa necessariamente diventare adulti. Columbia Pictures presenta in associazione con Relativity Media, una produzione di Happy Madison, un film di Dennis Dugan, Un weekend da bamboccioni. -

Friday, December 13, 2002

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Winter 12-13-2002 Volume 38 - Issue 10 - Friday, December 13, 2002 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 38 - Issue 10 - Friday, December 13, 2002" (2002). The Rose Thorn Archive. 288. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/288 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 38, ISSUE 10 R O S E -HU L M A N IN S TI T UT E OF TE C H N O L OG Y TERRE HAUTE, INDIANA FRIDAY DECEMBER 13, 2002 Explore Engineering Considering study abroad? hosts Robot Showdown require at least some college foreign have done programs in England, Nicole Hartkemeyer language class. -

DVD LIST 7-1-2018 Xlsx

Seawood Village Movie List 1155 9 1184 21 1015 300 348 1408 172 2012 1119 101 Dalmatians 1117 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 12 Rounds 862 12 Years a Slave 843 127 Hours 446 13 Going on 30 259 13 Hours 474 17 Again 208 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 21 Jump Street 737 22 JumpStreet 1145 27 Dresses 1079 3:10 to Yuma 1101 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 50 First Dates 1205 88 Minutes 177 A Beautiful Mind 444 A Brilliant Young Mind 643 A Bug's Life 255 A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 A Christmas Carol 581 A Christmas Story 1223 A Dog's Purpose 506 A Good Day to Die Hard 1120 A Hologram For The King 212 A Knights Tale 848 A League of Their Own 1222 A Mermaid's Tale 498 A Merry Friggin Christmas 1323 A Quiet Place 1273 A Star is Born 1108 Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter Page 1 of 33 Seawood Village Movie List 1322 Acromony 812 Act of Valor 819 Adams Family & Adams Family Values 1332 Adrift 83 Adventures in Zambezia 745 Aeon Flux 12 After Earth 585 Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 79 Alex Cross 198 Alexander and the terrible, Horrible, No Good 947 Ali 1004 Alice in Wonderland 525 Alice in Wonderland - Animated 1248 Alien Covenant 838 Aliens in the Attic 1262 All I Want For Christmas is You 1299 All The Money In The World 780 Allegiant 827 Aloha 1367 Alpha 1103 Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 522 Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked 854 Alvin and the Chipmonks Driving Dave Crazy 371 Alvin and The Chipmonks: The Road Chip 1272 American Assasin 1028 American Heist 1282 American -

Gregg Smrz Director / 2Nd Unit Director / Stunt Coordinator

GREGG SMRZ DIRECTOR / 2ND UNIT DIRECTOR / STUNT COORDINATOR DGA / SAG-AFTRA Representation: Holly Jeter 310-246-4008 Director: Medal of Honor – Hershey Director / Netflix / Director of Photography; Harris Done / 1st AD; Frederick Roth / Producers; Jack Rapke, Jackie Levine, Jack Molle, Brandon Birtell. Second Unit Director: Fantastic Four Second Unit Director / Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation / Director of Photography; Jonathon Taylor / 1st AD; Steve Danton / Production Manager; Haley Sweet / Producers; Bill Bannerman, Hutch Parker, Simon Kinberg. Mission Impossible V – Rogue Nation Second Unit Director / Paramount Studios / Director of Photography; Jonathon Taylor / 1st AD; Dominic Fysh / Production Manager; James Smith / Producers; J.J. Abrams, Bryan Burke, Tom Cruise, David Ellison, Dana Goldberg, Don Granger, Jake Myers, Daniel H. Stillman. Percy Jackson And The Sea of Monsters Second Unit Director / Fox Studios / Director of Photography; Roger Vernon / 1st AD; Morgan Beggs / Production Manager; Michael Williams / Unit Manager; Colleen Mitchell / Producers; Karen Rosenfelt, Chris Columbus, Michael Barnathan, Mark Radcliffe / Co-Producer; Bill Bannerman / Fox Studios Executive; David Starke. Alias (Multiple Episodes) Second Unit Director (Multiple Episodes) / ABC Entertainment / Director of Photography; Bing Sakowski / 1st AD; Suzanne Geiger / UPM; Bob Williams / Production Coordinator; Rex Camphuis / Executive Producers; J.J. Abrams, John Eisendrath, Ken Olin / Producer; Sarah Caplan. Hostage @ www.bmwfilms.com Second Unit Director / RSA Films / Producers; Arthur Anderson, Jules Daly, Tony McGarry, Ridley Scott, Tony Scott, Phillip Steuer / 1st AD; Arthur Anderson / 2nd AD; Jamie Marshall. The Hot Chick Second Unit Director / Touchstone Pictures / Director; Tom Brady / 1st AD; Cara Giallanza / 2nd AD; Chip Touhey / UPM; Udi Nedivi / Production Coordinator; Kelly Moran-Brown / Producers; John Schneider, Carr D'Angelo / Executive Producers; Jack Giarraputo, Adam Sandler, Guy Reidel / Co-Producers; Nathan Reiman, Ian Maxtone-Graham.